Academic Performance and Peer or Parental Tobacco Use among Non-Smoking Adolescents: Influence of Smoking Interactions on Intention to Smoke

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Smoking Experience

2.2.2. Academic Performance

2.2.3. Parental Tobacco Use

2.2.4. Intention to Smoke

2.2.5. Peer Tobacco Use

2.2.6. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Risk Factors for Adolescents’ Intention to Smoke

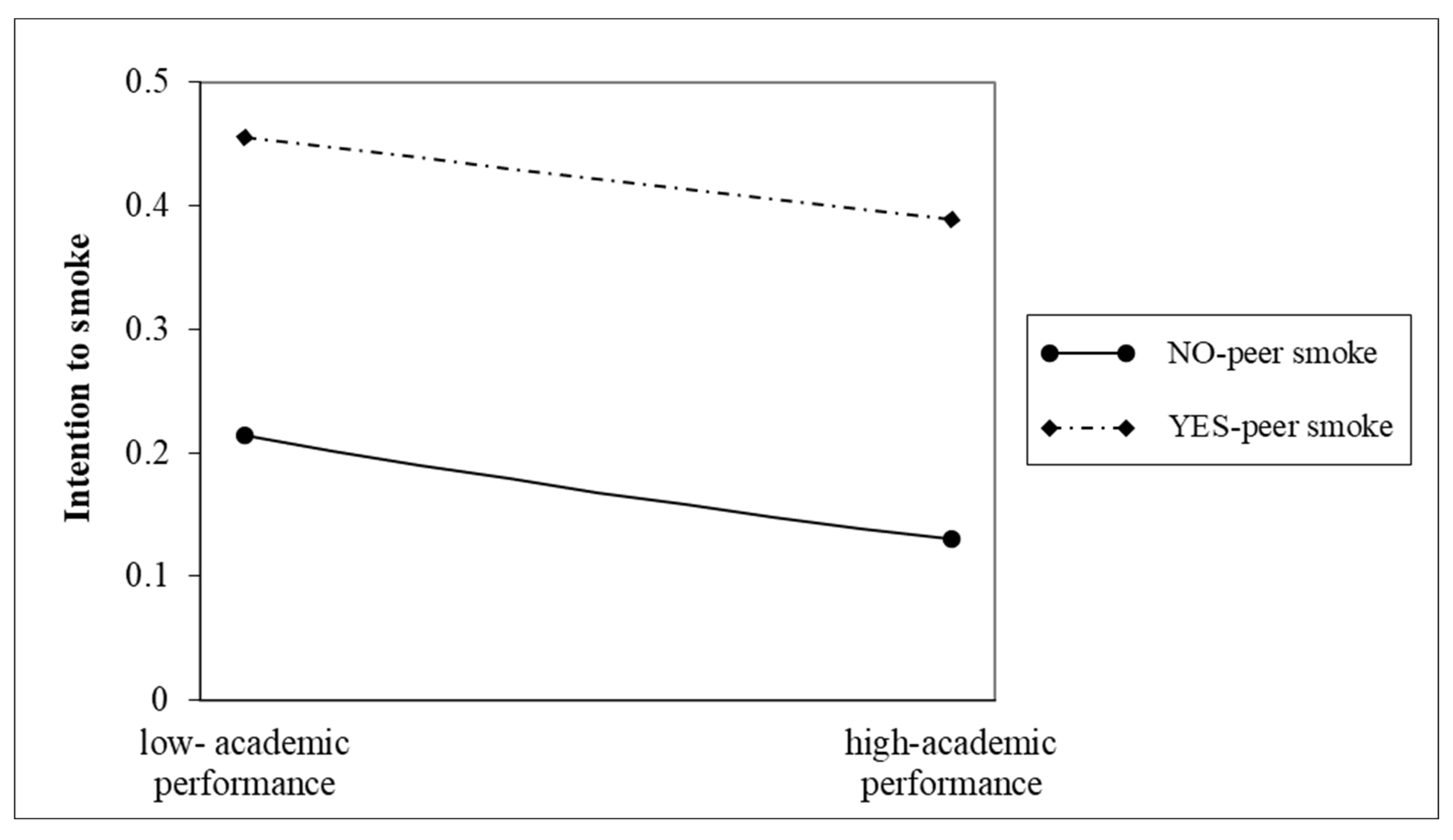

3.3. Academic Performance and Peer Smoking Interactions on the Intention to Smoke among Non-Smokers

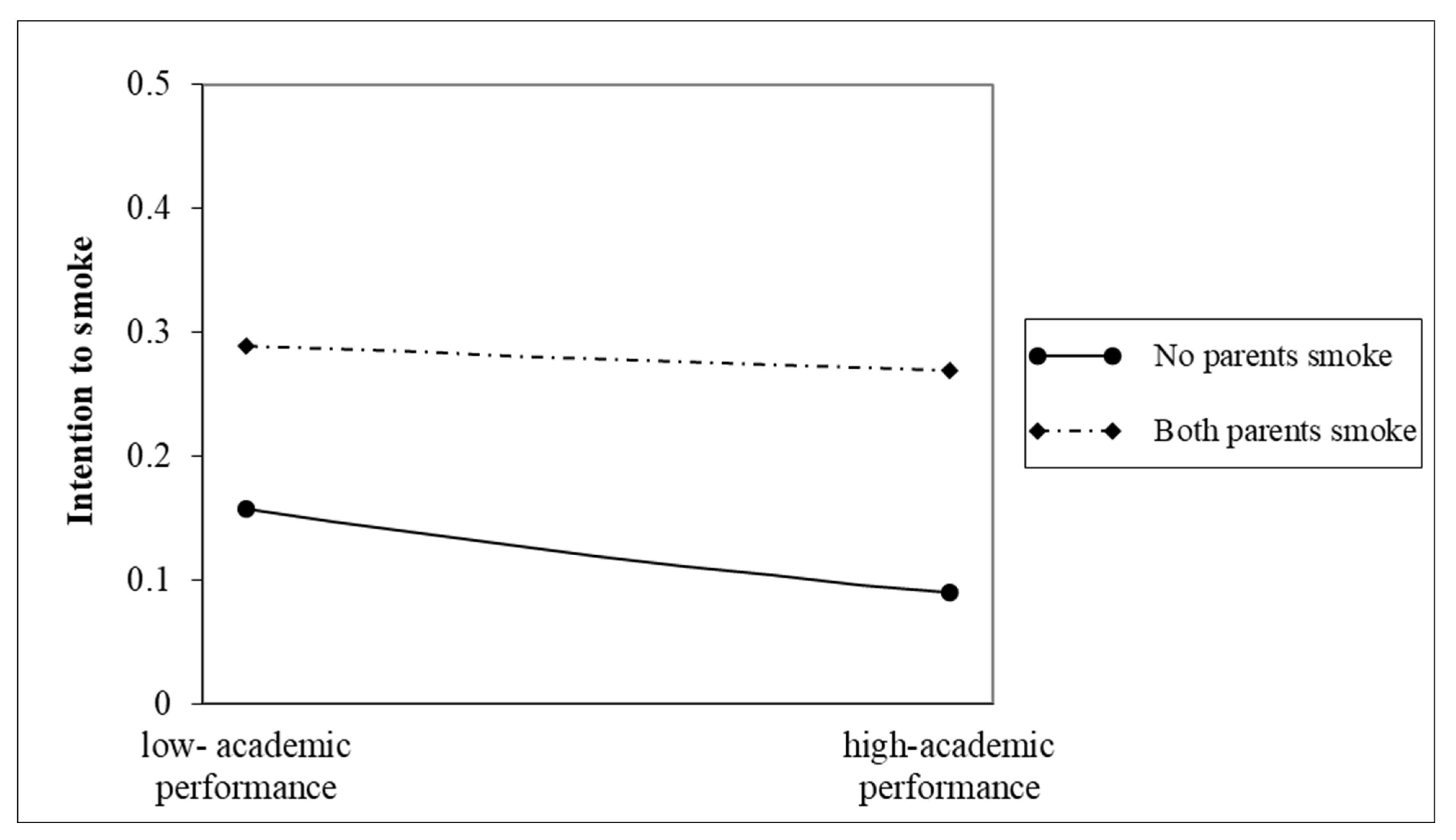

3.4. Academic Performance and Both Parents’ Smoking Interactions on the Intention to Smoke among Non-Smokers

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Youth Surveys-Tobacco Use and Smoking. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-HPR-TFI-2021.11.3 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Zhang, G.T.; Zhan, J.J.; Fu, H.Q. Trends in Smoking Prevalence and Intensity between 2010 and 2018: Implications for Tobacco Control in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosazadeh, M.; Amiresmaili, M.; Afshari, M. Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of the Smoking Prevalence in Mazandaran Province of Iran. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2015, 17, 10294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahwan, S.; Abdin, E.; Shafie, S.; Chang, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Teo, Y.Y.; Heng, D.; Chong, S.A.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of smoking and nicotine dependence: Results of a nationwide cross-sectional survey among Singapore residents. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alesci, N.L.; Forster, J.L.; Blaine, T. Smoking visibility, perceived acceptability, and frequency in various locations among youth and adults. Prev. Med. 2003, 36, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachiotis, G.; Siziya, S.; Muula, A.S.; Rudatsikira, E.; Papastergiou, P.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Determinants of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) among Non Smoking Adolescents (Aged 11–17 Years Old) in Greece: Results from the 2004-2005 GYTS Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.G.; Bernat, D.H.; Forster, J.L. Young adult perceptions of smoking in outdoor park areas. Health Place 2012, 18, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.; Kloska, D.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D.; Chaloupka, F.; Pierce, J.; Giovino, G.; Ruel, E.; Flay, B.R. The role of smoking intentions in predicting future smoking among youth: Findings from Monitoring the Future data. Addiction 2004, 99, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Blanton, H.; Russell, D.W. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1164–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.G.; Byrne, A.E.; Reinhart, M.I. Psychosocial correlates of adolescent cigarette-smoking—Personality or environment. Aust. J. Psychol. 1993, 45, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, H.P.; Mercken, L.; de Vries, H.; Oenema, A. A longitudinal study on determinants of the intention to start smoking among Non-smoking boys and girls of high and low socioeconomic status. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.F.; Littlecott, H.J.; Moore, L.; Ahmed, N.; Holliday, J. E-cigarette use and intentions to smoke among 10-11-year-old never-smokers in Wales. Tob. Control 2016, 25, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Gall, S.; Patterson, K.; Otahal, P.; Blizzard, L.; Patton, G.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A. Socioeconomic position over the life course from childhood and smoking status in mid-adulthood: Results from a 25-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidstrup, P.E.; Frederiksen, K.; Siersma, V.; Mortensen, E.L.; Ross, L.; Vinther-Larsen, M.; Gronbaek, M.; Johansen, C. Social-Cognitive and School Factors in Initiation of Smoking among Adolescents: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.A.; Hampson, S.E.; Barckley, M.; Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X. The effect of early cognitions on cigarette and alcohol use during adolescence. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.J.; Reilly, S.M. What Can Secondary School Students Teach Educators and School Nurses About Student Engagement in Health Promotion? A Scoping Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 33, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonell, C.; Parry, W.; Wells, H.; Jamal, F.; Fletcher, A.; Harden, A.; Thomas, J.; Campbell, R.; Petticrew, M.; Murphy, S.; et al. The effects of the school environment on student health: A systematic review of multi-level studies. Health Place 2013, 21, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.A.; Farrell, A.; Varano, S.P. Social control, serious delinquency, and risky behavior. Crime Delinq. 2008, 54, 423–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wiatrowski, M.D.; Griswold, D.B.; Roberts, M.K. Social-control Theory and delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1981, 46, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P.H. School delinquency and the school social bond. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1997, 34, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasarte, O.F.; Diaz, E.R.; Palacios, E.G.; Fernandez, A.R. The role of social support in school adjustment during Secondary Education. Psicothema 2020, 32, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkis, M.; Arslan, G.; Duru, E. The School Absenteeism among High School Students: Contributing Factors. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J.; Schneider, F.; Tueni, M.; de Vries, H. Is Academic Achievement Related to Mediterranean Diet, Substance Use and Social-Cognitive Factors: Findings from Lebanese Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkkinen, J.L.; Kinnunen, J.M.; Karvonen, S.; Hotulainen, R.H.; Lindfors, P.L.; Rimpela, A.H. Low schoolwork engagement and schoolwork difficulties predict smoking in adolescence? Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, J.M.; Lindfors, P.; Rimpela, A.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Rathmann, K.; Perelman, J.; Federico, B.; Richter, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Lorant, V. Academic well-being and smoking among 14-to 17-year-old schoolchildren in six European cities. J. Adolesc. 2016, 50, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennanen, M.; Haukkala, A.; De Vries, H.; Vartiainen, E. Academic achievement and smoking: Is self-efficacy an important factor in understanding social inequalities in Finnish adolescents? Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun Gwon, S.; Yan, G.; Kulbok, P.A. South Korean Adolescents’ Intention to Smoke. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, R.J.; Dugas, E.N.; Dutczak, H.; O’Loughlin, E.K.; Datta, G.D.; Lauzon, B.; O’Loughlin, J. Predictors of the Onset of Cigarette Smoking A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Population-Based Studies in Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennanen, M.; Haukkala, A.; de Vries, H.; Vartiainen, E. Longitudinal Study of Relations Between School Achievement and Smoking Behavior Among Secondary School Students in Finland: Results of the ESFA Study. Subst. Use Misuse 2011, 46, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Liu, D.Y.; Sharma, M.; Zhao, Y. Prevalence and Determinants of Current Smoking and Intention to Smoke among Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Survey among Han and Tujia Nationalities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Taxer, J.L.; Eskreis-Winkler, L.; Galla, B.M.; Gross, J.J. Self-Control and Academic Achievement. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Adams, N.E.; Beyer, J. Cognitive-processes mediating behavioral change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, M.D.; Skinner, W.F.; Massey, J.L.; Akers, R.L. Social-learning theory and adolescent cigarette-smoking—A longitudinal-study. Soc. Probl. 1985, 32, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, T.C.; Cullen, F.T.; Sellers, C.S.; Winfree, L.T.; Madensen, T.D.; Daigle, L.E.; Fearn, N.E.; Gau, J.M. The Empirical Status of Social Learning Theory: A Meta-Analysis. Justice Q. 2010, 27, 765–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.M.; Sher, K.J.; Cooper, M.L.; Wood, P.K. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use: Onset, persistence and trajectories of use across two samples. Addiction 2002, 97, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitória, P.; Pereira, S.E.; Muinos, G.; Vries, H.; Lima, M.L. Parents modelling, peer influence and peer selection impact on adolescent smoking behavior: A longitudinal study in two age cohorts. Addict. Behav. 2020, 100, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalici, F.; Schulz, P.J. Influence of Perceived Parent and Peer Endorsement on Adolescent Smoking Intentions: Parents Have More Say, But Their Influence Wanes as Kids Get Older. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauldry, S.; Shanahan, M.J.; Macmillan, R.; Miech, R.A.; Boardman, J.D.; Dean, O.D.; Cole, V. Parental and adolescent health behaviors and pathways to adulthood. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 58, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction 2003, 98, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Simons-Morton, B.G.; Farhart, T.; Luk, J.W. Socio-Demographic Variability in Adolescent Substance Use: Mediation by Parents and Peers. Prev. Sci. 2009, 10, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, C.; Piazza, M.; Mekos, D.; Valente, T. Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. J. Adolesc. Health 2001, 29, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.; Kremers, S.P.J.; de Vries, H. Why do Danish adolescents take up smoking? Eur. J. Public Health 2003, 13, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons-Morton, B.G.; Farhat, T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human-development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.P.; Choi, W.S.; Gilpin, E.A.; Farkas, A.J.; Merritt, R.K. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R. A study of children’s conceptions of school rules by investigating their judgements of transgressions in the absence of rules. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.A. Addressing Common Risk and Protective Factors Can Prevent a Wide Range of Adolescent Risk Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Han, H.; Zhuang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, P.; Yao, Y. Tobacco Use and Exposure to Second-Hand Smoke among Urban Residents: A Community-Based Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9799–9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, C.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Brown, A.; Hastings, G.B. Tobacco marketing awareness on youth smoking susceptibility and perceived prevalence before and after an advertising ban. Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 18, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azagba, S.; Baskerville, N.B.; Foley, K. Susceptibility to cigarette smoking among middle and high school e-cigarette users in Canada. Prev. Med. 2017, 103, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemstra, M.; Otten, R.; de Leeuw, R.N.H.; van Schayck, O.C.P.; Engels, R. The Changing Role of Self-Efficacy in Adolescent Smoking Initiation. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, R.; Bauld, L.; Amos, A.; Fidler, J.A.; Munafò, M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1248, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Smith, J.L.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Bazargan, M. Cigarette Smoking among Economically Disadvantaged African-American Older Adults in South Los Angeles: Gender Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Schwarzer, R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs—A chinese adaptation of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia 1995, 38, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, G.; Reutter, M.; Strohmaier, K. Goodbye Smokers’ Corner Health Effects of School Smoking Bans. J. Hum. Resour. 2020, 55, 1068–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Yang, G.H.; Wan, X. ‘Pro-tobacco propaganda’: A case study of tobacco industry-sponsored elementary schools in China. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, L.H.; Osler, M.; Roberts, C.; Due, P.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Holstein, B.E. Exposure to teachers smoking and adolescent smoking behaviour: Analysis of cross sectional data from Denmark. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.C.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Sun, X.B. Smoking dynamics with health education effect. Aims Math. 2018, 3, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakete, G.; Strunk, M.; Lang, P. Smoking prevention in schools. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundh. Gesundh. 2010, 53, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elstad, J.I. Indirect health-related selection or social causation? Interpreting the educational differences in adolescent health behaviours. Soc. Theory Health 2010, 8, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, A.A.; Popp, A.M.; Latimore, T.L.; Shekarkhar, Z.; Koo, D.J. Social Control Theory and School Misbehavior: Examining the Role of Race and Ethnicity. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2011, 9, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Kim, H.; Ma, J. School Bonds and the Onset of Substance Use among Korean Youth: An Examination of Social Control Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2923–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignery, K.; Laurier, W. Achievement in student peer networks: A study of the selection process, peer effects and student centrality. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollub, E.A.; Kennedy, B.M.; Bourgeois, B.F.; Broyles, S.T.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Engaging Communities to Develop and Sustain Comprehensive Wellness Policies: Louisiana’s Schools Putting Prevention to Work. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yzer, M.; van den Putte, B. Control perceptions moderate attitudinal and normative effects on intention to quit smoking. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M.B.; Walker, M.W.; Alexander, T.N.; Jordan, J.W.; Wagner, D.E. Why Peer Crowds Matter: Incorporating Youth Subcultures and Values in Health Education Campaigns. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.Z.Y.; Anderson, J.G.; Yang, T.Z. Impact of Role Models and Policy Exposure on Support for Tobacco Control Policies in Hangzhou, China. Am. J. Health Behav. 2014, 38, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoli, C.T.; Kodet, J. A systematic review of secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and smoking behaviors: Smoking status, susceptibility, initiation, dependence, and cessation. Addict. Behav. 2015, 47, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, T.P.; Lizotte, A.J.; Krohn, M.D.; Farnworth, M.; Jang, S.J. Testing interactional theory—An examination of reciprocal causal relationships among family, school, and delinquency. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 1991, 82, 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth, R.; Randall, G.K.; Shin, C.; Redmond, C. Randomized study of combined universal family and school preventive interventions: Patterns of long-term effects on initiation, regular use, and weekly drunkenness. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005, 19, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Not Intend to Smoke | Intend to Smoke | Total | χ2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n | ||||

| Sex | girls | 4218 (91.20) | 407 (8.80) | 4625 | 85,100 | <0.001 |

| boys | 4055 (85.03) | 714 (14.97) | 4769 | |||

| Age | ~10 | 1018 (92.63) | 81 (7.37) | 1099 | 152,448 | <0.001 |

| ~12 | 3505 (91.37) | 331 (8.63) | 3836 | |||

| ~14 | 3248 (85.32) | 559 (14.68) | 3807 | |||

| ≥15 | 362 (76.37) | 112 (23.63) | 474 | |||

| Mother’s education level | middle school and below | 3953 (87.32) | 574 (12.68) | 4527 | 23,669 | <0.001 |

| high school | 3053 (87.65) | 430 (12.35) | 3483 | |||

| undergraduate and above | 1234 (92.09) | 106 (7.91) | 1340 | |||

| Father’s education level | middle school and below | 3770 (86.81) | 573 (13.19) | 4343 | 28,021 | <0.001 |

| high school | 3167 (88.27) | 421 (11.73) | 3588 | |||

| undergraduate and above | 1296 (92.05) | 112 (7.95) | 1408 | |||

| Family structure | nuclear family | 4292 (88.35) | 566 (11.65) | 4858 | 39,118 | <0.001 |

| stem family | 2058 (90.70) | 211 (9.30) | 2269 | |||

| other family | 1903 (84.73) | 343 (15.27) | 2246 | |||

| General self-efficacy | <20 | 1333 (82.44) | 284 (17.56) | 1617 | 100,525 | <0.001 |

| 20–30 | 4801 (87.72) | 672 (12.28) | 5473 | |||

| >30 | 2133 (92.90) | 163 (7.10) | 2296 | |||

| Academic performance | poorest | 546 (79.13) | 144 (20.87) | 690 | 158,305 | <0.001 |

| lower 20% | 1552 (83.08) | 316 (16.92) | 1868 | |||

| middle 20% | 3193 (88.79) | 403 (11.21) | 3596 | |||

| higher 20% | 2247 (91.08) | 220 (8.92) | 2467 | |||

| excellent | 711 (95.44) | 34 (4.56) | 745 | |||

| Peer smoking | no | 7359 (90.63) | 761 (9.37) | 8120 | 376,446 | <0.001 |

| yes | 857 (71.24) | 346 (28.76) | 1203 | |||

| Parental smoking | no parents smoke | 4073 (91.08) | 399 (8.92) | 4472 | 111,128 | <0.001 |

| only mother smoke | 114 (80.85) | 27 (19.15) | 141 | |||

| only father smoke | 3712 (86.37) | 586 (13.63) | 4298 | |||

| both parents smoke | 341 (76.80) | 103 (23.20) | 444 | |||

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex(ref = girls) | |||||

| Boys | 0.466 | 0.071 | <0.001 | 1.59 | 1.39–1.83 |

| Age | 0.158 | 0.025 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.11–1.23 |

| Family structure (ref = nuclear family) | |||||

| Stem family | −0.155 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 0.86 | 0.72–1.02 |

| Other family | 0.205 | 0.080 | 0.011 | 1.23 | 1.05–1.44 |

| Mother’s education level (ref = middle school) | |||||

| High school | 0.194 | 0.090 | 0.031 | 1.21 | 1.02–1.45 |

| Undergraduate and above | 0.071 | 0.155 | 0.647 | 1.07 | 0.79–1.45 |

| Father’s education level (ref = middle school) | |||||

| High school | −0.019 | 0.090 | 0.831 | 0.98 | 0.82–1.17 |

| Undergraduate and above | −0.137 | 0.153 | 0.372 | 0.87 | 0.65–1.18 |

| General self-efficacy | −0.025 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 |

| Academic performance | −0.226 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.75–0.85 |

| Parents smoke (ref = no parents smoking) | |||||

| Only mother | 0.460 | 0.243 | 0.059 | 1.58 | 0.98–2.55 |

| Only father | 0.412 *** | 0.074 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.31–1.74 |

| Both parents | 0.836 *** | 0.137 | <0.001 | 2.31 | 1.77–3.02 |

| Peer smoking (ref = no) | |||||

| Yes | 1.073 *** | 0.081 | <0.001 | 2.92 | 2.49–3.43 |

| Academic Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| No-peer smoking | −0.274 *** | 0.041 | 0.76 | 0.70–0.82 |

| Yes-peer smoking | −0.183 ** | 0.065 | 0.83 | 0.73–0.95 |

| No parents smoking | −0.326 *** | 0.056 | 0.72 | 0.65–0.81 |

| Only mother smoking | −0.046 | 0.235 | 0.96 | 0.60–1.51 |

| Only father smoking | −0.227 *** | 0.047 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.87 |

| Both parents’ smoking | −0.021 | 0.122 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.24 |

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: | ||||

| Academic performance | −0.395 *** | 0.038 | 0.67 | 0.63–0.73 |

| Yes-peer smoking | 1.358 *** | 0.078 | 3.89 | 3.34–4.53 |

| Academic performance × Yes-peer smoking | 0.188 ** | 0.070 | 1.21 | 1.05–1.38 |

| Model 2: | ||||

| Academic performance | −0.439 *** | 0.051 | 0.64 | 0.58–0.71 |

| Only mother smoking | 0.886 *** | 0.244 | 2.42 | 1.50–3.91 |

| Only father smoking | 0.472 *** | 0.072 | 1.60 | 1.39–1.85 |

| Both parents smoking | 1.140 *** | 0.132 | 3.13 | 2.42–4.05 |

| Academic performance × Only mother smoking | 0.415 | 0.218 | 1.52 | 0.99–2.32 |

| Academic performance × Only father smoking | 0.082 | 0.068 | 1.09 | 0.95–1.24 |

| Academic performance × Both parents’ smoking | 0.330 ** | 0.121 | 1.39 | 1.10–1.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, A.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Hu, B.; Chen, Y.; Cui, P.; Li, J. Academic Performance and Peer or Parental Tobacco Use among Non-Smoking Adolescents: Influence of Smoking Interactions on Intention to Smoke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021048

Zhou A, Li X, Song Y, Hu B, Chen Y, Cui P, Li J. Academic Performance and Peer or Parental Tobacco Use among Non-Smoking Adolescents: Influence of Smoking Interactions on Intention to Smoke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021048

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Angdi, Xinru Li, Yiwen Song, Bingqin Hu, Yitong Chen, Peiyao Cui, and Jinghua Li. 2023. "Academic Performance and Peer or Parental Tobacco Use among Non-Smoking Adolescents: Influence of Smoking Interactions on Intention to Smoke" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021048

APA StyleZhou, A., Li, X., Song, Y., Hu, B., Chen, Y., Cui, P., & Li, J. (2023). Academic Performance and Peer or Parental Tobacco Use among Non-Smoking Adolescents: Influence of Smoking Interactions on Intention to Smoke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021048