A Review of the Role of the School Spatial Environment in Promoting the Visual Health of Minors

Abstract

1. Introduction

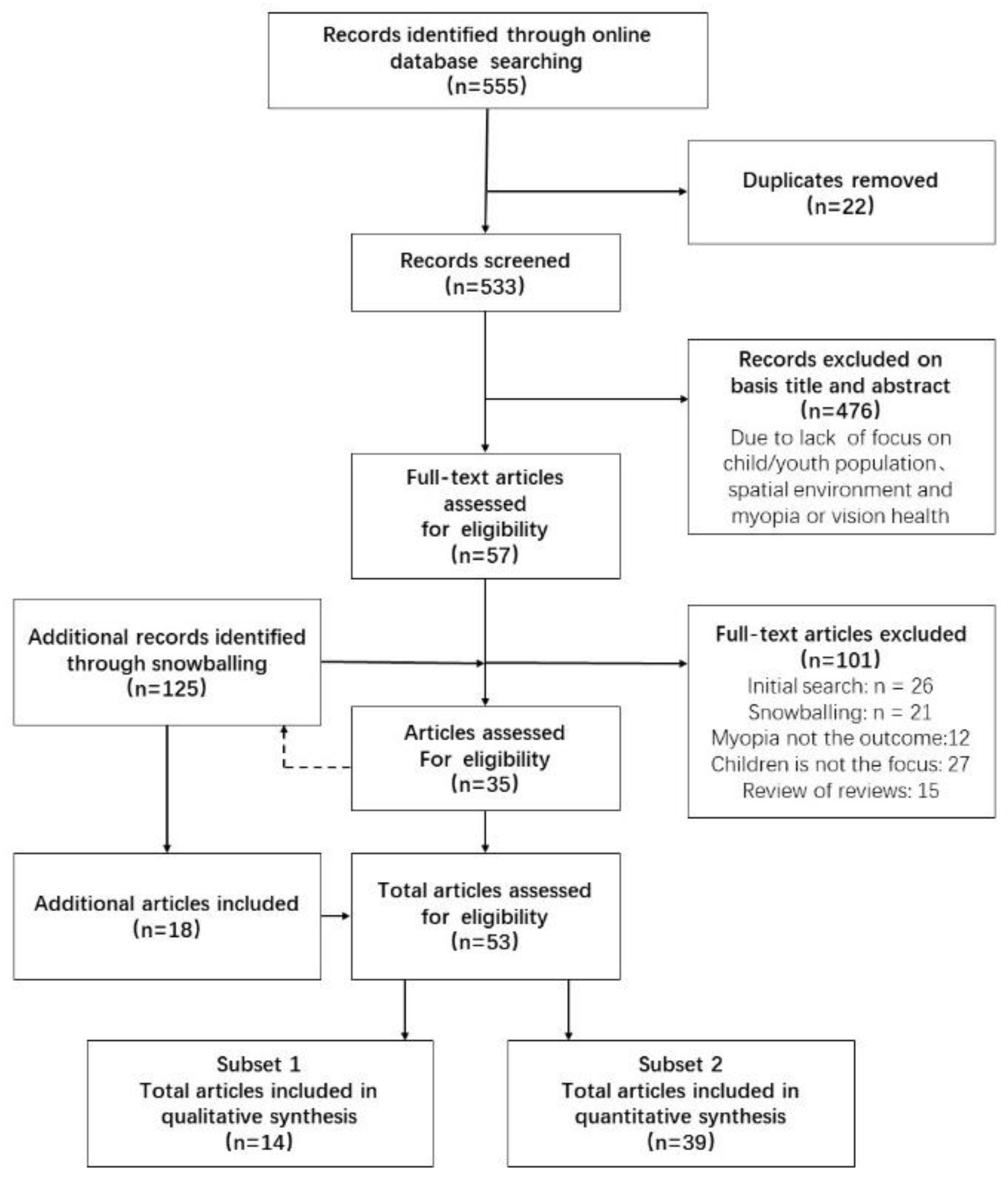

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Strong evidence came from longitudinal cluster randomized or cluster matched controlled trials that were conducted in school environments. These contained obvious built environmental elements and minor behaviors and could be directly oriented to architectural design.

- Moderate evidence came from longitudinal approaches with smaller, single-site samples and a comparison or control group. These included placing the surrounding environment or behavior in a social context, and this served to indirectly orientate architectural design.

- Preliminary evidence first came from case studies related to visual health and then also from medical or genetic research where the associated pathogenic factors are difficult to regulate or modify—this played an indirect but fundamental role in guiding architecture design.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Articles

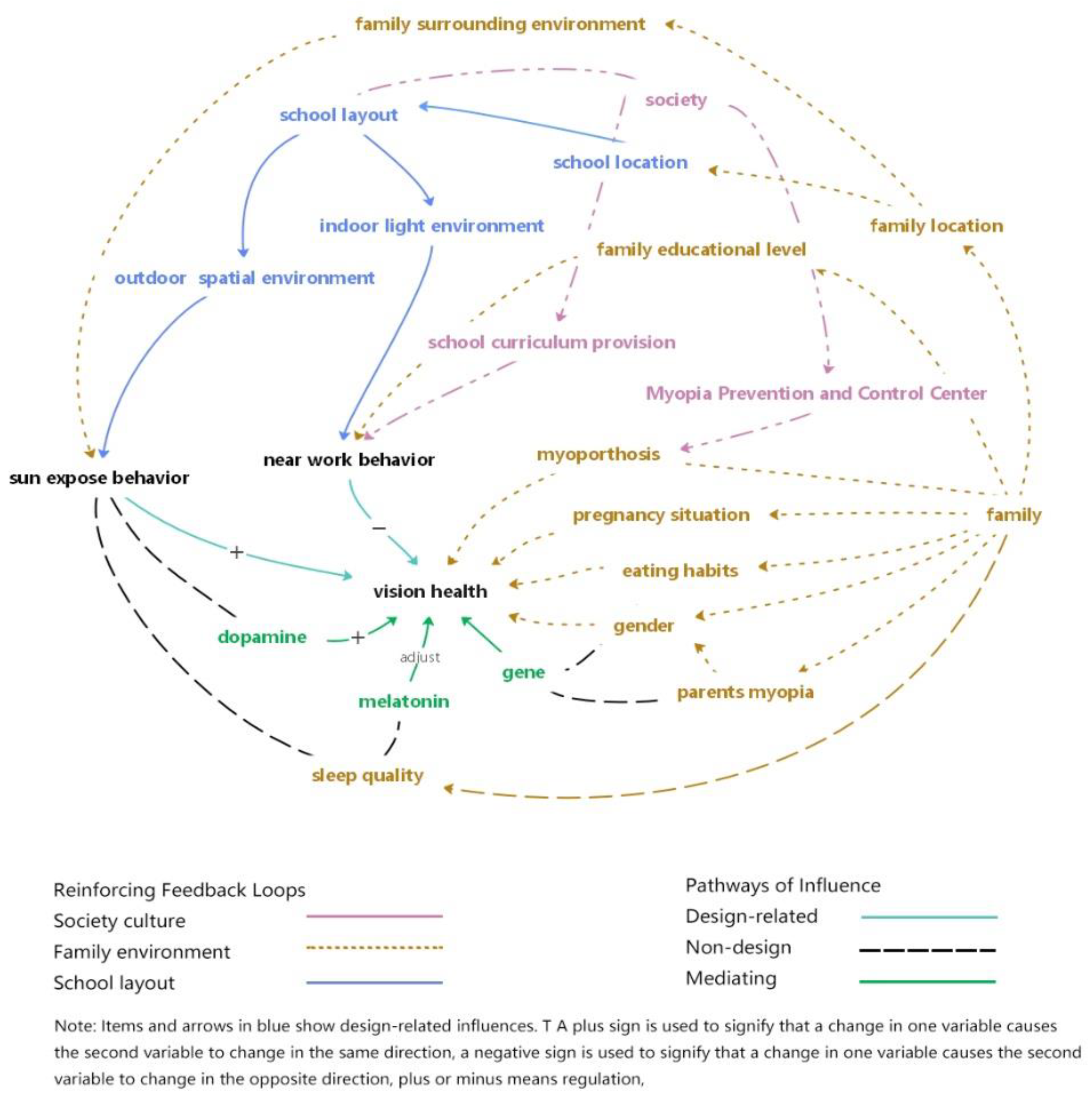

3.2. Description of the Visual Health Loop

3.2.1. Medical Related Research

- genetic inheritance

- peripheral refractive error

3.2.2. Environment Related Studies

- educational environment

- spatial environment

- outdoor environment

3.2.3. Behavior Related Studies

- negative behaviors related to visual health

- positive behaviors related to visual health

3.3. Visual Health Guidelines for School Architecture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rainey, L.; Elsman, E.B.M.; van Nispen, R.M.A.; van Leeuwen, L.M.; van Rens, G.H.M.B. Comprehending the impact of low vision on the lives of children and adolescents: A qualitative approach. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2633–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergott, R.C. Depression and Anxiety in Visually Impaired Older People. Yearb. Ophthalmol. 2007, 2007, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillmann, L. Stopping the rise of myopia in Asia. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 258, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, B.A.; Fricke, T.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Resnikoff, S. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2020/52320/twwd/202008/t20200827_480590.html (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Grzybowski, A.; Kanclerz, P.; Tsubota, K.; Lanca, C.; Saw, S.-M. A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Architectural Space Environment and Behavior; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2009; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.-W.; Ramamurthy, D.; Saw, S.-M. Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2011, 32, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jin, W. Relationship between near work and the development of myopia in adolescents. Zhonghua Shiyan Yanke Zazhi/Chin. J. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 39, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Report on Vision. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516570 (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Xu, S.; Sun, C. Prevalence, associates and stage-specific preventive behaviors of myopia among junior high school students in Guangdong province: Health action process approach- and theory of planned behavior-based analysis. Chin. J. Public Health 2022, 38, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.-J.; Jin, J.-X.; Wu, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-W.; Jiang, X.; Gao, G.-P.; Tao, F.-B. Elevated light levels in schools have a protective effect on myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2015, 35, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, V.; Hinterlong, J.E.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Tsai, J.-C.; Wu, J.S.; Liou, Y.M. A Nationwide Study of Myopia in Taiwanese School Children: Family, Activity, and School-Related Factors. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 37, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterlong, J.E.; Holton, V.L.; Chiang, C.C.; Tsai, C.Y.; Liou, Y.M. Association of multimedia teaching with myopia: A national study of school children. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3643–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Tang, P.; Lv, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.; Xu, L.; Jonas, J.B. Outdoor activity and myopia progression in 4-year follow-up of Chinese primary school children: The Beijing Children Eye Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Duan, J.L.; Liu, L.J.; Sun, Y.; Tang, P.; Lv, Y.Y.; Jonas, J.B. High myopia in Greater Beijing School Children in 2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berticat, C.; Mamouni, S.; Ciais, A.; Villain, M.; Raymond, M.; Daien, V. Probability of myopia in children with high refined carbohydrates consumption in France. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assem, A.S.; Tegegne, M.M.; Fekadu, S.A. Prevalence and associated factors of myopia among school children in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, S.A.; Collins, M.J.; Vincent, S.J. Light Exposure and Physical Activity in Myopic and Emmetropic Children. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2014, 91, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.B.; Cao, X.; Wang, M.; Jin, N.X.; Gong, Y.X.; Xiong, Y.J.; Cai, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; et al. Prevalence of myopia and influencing factors among high school students in Nantong, China: A cross-sectional study. Ophthalmic Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, J.; Xu, H. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Myopia among Third-Grade Primary School Students in the Gongshu District of Hangzhou. Chin. J. Optom. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 21, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.J.; You, Q.S.; Duan, J.L.; Luo, Y.X.; Liu, L.J.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Zhu, H.P.; He, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Prevalence and associated factors of myopia in high-school students in Beijing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Luensmann, D.; Fonn, D.; Woods, J.; Jones, D.; Gordon, K.; Jones, L. Myopia prevalence in Canadian school children: A pilot study. Eye 2018, 32, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.L.; Xie, Z.K.; Zhou, F.; Hu, L. Myopia prevalence and influencing factor analysis of primary and middle school students in our country. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013, 93, 999–1002. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Gao, G.; Jin, J.; Hua, W.; Tao, L.; Xu, S.; Tao, F. Housing type and myopia: The mediating role of parental myopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenbo, L.; Congxia, B.; Hui, L. Genetic and environmental-genetic interaction rules for the myopia based on a family exposed to risk from a myopic environment. Gene 2017, 626, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, D.J.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Niu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Pan, C.W. Myopia among school students in rural China (Yunnan). Ophthalmic. Physiol. Opt. 2016, 36, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Vashist, P.; Tandon, R.; Pandey, R.M.; Bhardawaj, A.; Menon, V.; Mani, K. Prevalence of Myopia and Its Risk Factors in Urban School Children in Delhi: The North India Myopia Study (NIM Study). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Vashist, P.; Tandon, R.; Pandey, R.M.; Bhardawaj, A.; Gupta, V.; Menon, V. Incidence and progression of myopia and associated factors in urban school children in Delhi: The North India Myopia Study (NIM Study). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, T.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Lim, K.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Baek, S.-H. Body Stature as an Age-Dependent Risk Factor for Myopia in a South Korean Population*. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 32, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhu, J.; Xu, X.; Lu, L.; Zhao, R.; Zou, H. Different patterns of myopia prevalence and progression between internal migrant and local resident school children in Shanghai, China: A 2-year cohort study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, K.; Suhr Thykjaer, A.; Søgaard Hansen, R.; Vestergaard, A.H.; Jacobsen, N.; Goldschmidt, E.; Grauslund, J. Physical activity and myopia in Danish children—The CHAMPS Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017, 96, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Naduvilath, T.J.; Wang, J.; Xiong, S.; He, X.; Xu, X.; Sankaridurg, P.R. Sleeping late is a risk factor for myopia development amongst school-aged children in China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Gao, T.Y.; Vasudevan, B.; Ciuffreda, K.J.; Liang, Y.B.; Jhanji, V.; Wang, N.L. Near work, outdoor activity, and myopia in children in rural China: The Handan offspring myopia study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.H.; Han, J.; Chung, T.-Y.; Kang, S.; Yim, H.W. The high prevalence of myopia in Korean children with influence of parental refractive errors: The 2008–2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M.; Li, S.-Y.; Kang, M.-T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.-R.; Li, H. Near Work Related Parameters and Myopia in Chinese Children: The Anyang Childhood Eye Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Ding, W.; Ji, R.; Tian, Y.; Long, K.; Yu, H.; Guo, Z. Effect of Sunshine Duration on Myopia in Primary School Students from Northern and Southern China. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 4913–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Seo, J.S.; Yoo, W.-S.; Kim, G.-N.; Kim, R.B.; Chae, J.E.; Kim, S.J. Factors associated with myopia in Korean children: Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey 2016–2017 (KNHANES VII). BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-T.; Li, S.-M.; Peng, X.; Li, L.; Ran, A.; Meng, B.; Wang, N. Chinese Eye Exercises and Myopia Development in School Age Children: A Nested Case-control Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.X.; Bi, H.S.; Wu, J.F.; Jiang, W.J.; Panda-Jonas, S. Education-Related Parameters in High Myopia: Adults versus School Children. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-X.; Hua, W.-J.; Jiang, X.; Wu, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-W.; Gao, G.-P.; Tao, F.-B. Effect of outdoor activity on myopia onset and progression in school-aged children in northeast china: The sujiatun eye care study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, J.M.; Rose, K.A.; Morgan, I.G.; Burlutsky, G.; Mitchell, P. Myopia and the Urban Environment: Findings in a Sample of 12-Year-Old Australian School Children. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Jang, J.; Yang, H.K.; Hwang, J.-M.; Park, S. Prevalence and risk factors of myopia in adult Korean population: Korea national health and nutrition examination survey 2013–2014 (KNHANES VI). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Xu, L.; Tang, P.; Lv, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.; Jonas, J.B. Myopic Shift and Outdoor Activity among Primary School Children: One-Year Follow-Up Study in Beijing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yang, J.; Mai, J.; Du, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.-H. Prevalence and associated factors of myopia among primary and middle school-aged students: A school-based study in Guangzhou. Eye 2016, 30, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Bai, N.; Xu, H.; Lu, P.; Jiang, Z. An Epidemiological Survey on Myopia and Related Factors among Rural and Urban Adolescents in Xingyi City of Guizhou Province. Chin. J. Optom. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 23, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Chang, K.; Shen, E.; Luo, K.-S.; Ying, Y.-H. Risk Factors and Behaviours of Schoolchildren with Myopia in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaki, M.; Torii, H.; Tsubota, K.; Negishi, K. Decreased sleep quality in high myopia children. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atowa, U.C.; Wajuihian, S.O.; Munsamy, A.J. Associations between near work, outdoor activity, parental myopia and myopia among school children in Aba, Nigeria. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 13, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, R.; Verkicharla, P. Increasing Time in Outdoor Environment Could Counteract the Rising Prevalence of Myopia in Indian School-Going Children. Curr. Sci. 2020, 119, 1616–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walline, J.J. Myopia Control: A Review. Eye Contact Lens. 2016, 42, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, S.M.; Chua, W.H.; Wu, H.M.; Yap, E.; Chia, K.S.; Stone, R.A. Myopia: Gene-environment interaction. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2000, 29, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramamurthy, D.; Chua, S.Y.L.; Saw, S.M. A review of environmental risk factors for myopia during early life, childhood and adolescence. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2015, 98, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, F. Educational Environment: The Most Powerful Factor for the Onset and Development of Myopia among Students. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2021, 52, 895–900. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Kurihara, T.; Torii, H.; Tsubota, K. Progress and Control of Myopia by Light Environments. Eye Contact Lens Sci. Clin. Pract. 2018, 4, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza Moyano, D.; González-Lezcano, R.A. Pandemic of Childhood Myopia. Could New Indoor LED Lighting Be Part of the Solution? Energies 2021, 14, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Naduvilath, T.; Zang, J.; Zou, H.; Zhu, J.; Xu, X. Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017, 95, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, F.; Liang, G.; Pan, C.W. Gene-environment Interaction in Spherical Equivalent and Myopia: An Evidence-based Review. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022, 29, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, E.; Jacobsen, N. Genetic and environmental effects on myopia development and progression. Eye 2013, 28, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, S.-M.; Carkeet, A.; Chia, K.-S.; Stone, R.A.; Tan, D.T. Component dependent risk factors for ocular parameters in Singapore Chinese children. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti, D.O.; Mitchell, G.L.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Jones, L.A.; Zadnik, K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children’s refractive error. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar]

- French, A.N.; Ashby, R.S.; Morgan, I.G.; Rose, K.A. Time outdoors and the prevention of myopia. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 114, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, G.C.; Hanifin, J.P.; Greeson, J.M.; Byrne, B.; Glickman, G.; Gerner, E.; Rollag, M.D. Action Spectrum for Melatonin Regulation in Humans: Evidence for a Novel Circadian Photoreceptor. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 6405–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, J.M.; Huynh, S.C.; Robaei, D.; Rose, K.A.; Morgan, I.G.; Smith, W.; Mitchell, P. Ethnic Differences in the Impact of Parental Myopia: Findings from a Population-Based Study of 12-Year-Old Australian Children. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadnik, K. The Effect of Parental History of Myopia on Children’s Eye Size. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994, 271, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Qi, P. The increasing prevalence of myopia in junior high school students in the Haidian District of Beijing, China: A 10-year population-based survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Guo, X.; Tideman JW, L.; Williams, K.M.; Yazar, S.; Evans, D.M. Childhood gene-environment interactions and age-dependent effects of genetic variants associated with refractive error and myopia: The CREAM Consortium. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysi, P.G.; Choquet, H.; Khawaja, A.P.; Wojciechowski, R.; Tedja, M.S. Meta-analysis of 542,934 subjects of European ancestry identifies new genes and mechanisms predisposing to refractive error and myopia. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, L. Relationship of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity With Myopia Progression and Axial Elongation in the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2005, 123, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-C.; Chuang, M.-N.; Choi, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, G.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Cheung, C.M.G. Update in myopia and treatment strategy of atropine use in myopia control. Eye 2018, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Ramamirtham, R.; Qiao-Grider, Y.; Hung, L.-F.; Huang, J.; Kee, C.; Paysse, E. Effects of Foveal Ablation on Emmetropization and Form-Deprivation Myopia. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti, D.O.; Hayes, J.R.; Mitchell, G.L.; Jones, L.A.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Cotter, S.A.; Zadnik, K. Refractive Error, Axial Length, and Relative Peripheral Refractive Error before and after the Onset of Myopia. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sankaridurg, P.; Donovan, L.; Lin, Z.; Li, L.; Martinez, A.; Ge, J. Characteristics of peripheral refractive errors of myopic and non-myopic Chinese eyes. Vis. Res. 2010, 50, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutti, D.O.; Sholtz, R.I.; Friedman, N.E.; Zadnik, K. Peripheral refraction and ocular shape in children. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sng, C.C.A.; Lin, X.-Y.; Gazzard, G.; Chang, B.; Dirani, M.; Chia, A.; Saw, S.-M. Peripheral Refraction and Refractive Error in Singapore Chinese Children. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sng, C.C.A.; Lin, X.-Y.; Gazzard, G.; Chang, B.; Dirani, M.; Lim, L.; Saw, S.-M. Change in Peripheral Refraction over Time in Singapore Chinese Children. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodstein, R.S.; Brodstein, D.E.; Olson, R.J.; Hunt, S.C.; Williams, R.R. The Treatment of Myopia with Atropine and Bifocals. Ophthalmology 1984, 91, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, T.W.; Goldschmidt, E. Myopia and its relationship to education, intelligence and height: Preliminary results from an on-going study of Danish draftees. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009, 66, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.Y.; Foster, P.J.; Ng, T.P.; Tielsch, J.M.; Johnson, G.J.; Seah, S.K. Variations in ocular biometry in an adult Chinese population in Singapore: The Tanjong Pagar Survey. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.S.; Saw, S.-M.; Jeganathan, V.S.E.; Tay, W.T.; Aung, T.; Tong, L.; Wong, T.Y. Distribution and Determinants of Ocular Biometric Parameters in an Asian Population: The Singapore Malay Eye Study. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, K.A. Myopia, Lifestyle, and Schooling in Students of Chinese Ethnicity in Singapore and Sydney. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008, 126, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, I.; Rose, K. How genetic is school myopia? Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2005, 24, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, T.; Li, J.; Jonas, J.B. Causes of Blindness and Visual Impairment in Urban and Rural Areas in Beijing. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1134.e1–1134.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiafe, B. Ghana Blindness and Vision Impairment Study. International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. 2015. Available online: https://www.iapb.org/vision2020/ghana-nationalblindness-and-visual-impairment-study/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Ko, D.-H.; Elnimeiri, M.; Clark, R.J. Assessment and prediction of daylight performance in high-rise office buildings. Struct. Design Tall Spec. Build. 2008, 17, 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y. Study on Healthy Daytime Lighting in Classrooms in Chongqing; Chongqing University: Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Durna, B.; Şahin, A.D. Mapping of daylight illumination levels using global solar radiation data in and around Istanbul, Turkey. Weather 2020, 75, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-W.; Wu, R.-K.; Li, J.; Zhong, H. Low prevalence of myopia among school children in rural China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, B.; Trites, S.; Janssen, I. Relations between the school physical environment and school social capital with student physical activity levels. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.A.; Morgan, I.G.; Ip, J.; Kifley, A.; Huynh, S.; Smith, W.; Mitchell, P. Outdoor Activity Reduces the Prevalence of Myopia in Children. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Sinnott, L.T.; Mutti, D.O.; Mitchell, G.L.; Moeschberger, M.L.; Zadnik, K. Parental History of Myopia, Sports and Outdoor Activities, and Future Myopia. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, I.G. Myopia Prevention and Outdoor Light Intensity in a School-based Cluster Randomized Trial. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1251–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, R.S.; Schaeffel, F. The Effect of Bright Light on Lens Compensation in Chicks. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Belkin, M.; Yehezkel, O.; Solomon, A.S.; Polat, U. Dependency between light intensity and refractive development under light-dark cycles. Exp. Eye Res. 2011, 92, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Nowroozzadeh, M.H. Outdoor activity and myopia. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 1229–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Cai, H.; Li, X. Non-visual effects of indoor light environment on humans: A review. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 228, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, J.M.; Saw, S.-M.; Rose, K.A.; Morgan, I.G.; Kifley, A.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P. Role of Near Work in Myopia: Findings in a Sample of Australian School Children. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Morgan, I.G.; Chen, Q.; Jin, L.; He, M.; Congdon, N. Disordered sleep and myopia risk among Chinese children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, S.M.; Chan, B.; Seenyen, L.; Yap, M.; Tan, D.; Chew, S.J. Myopia in Singapore kindergarten children. Optometry 2001, 72, 286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Jordan, L.A.; Mitchell, G.L.; Cotter, S.A.; Kleinstein, R.N.; Manny, R.E.; Mutti, D.O.; Zadnik, K. Visual Activity before and after the Onset of Juvenile Myopia. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deere, K.; Williams, C.; Leary, S.; Mattocks, C.; Ness, A.; Blair, S.N.; Riddoch, C. Myopia and later physical activity in adolescence: A prospective study. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2009, 43, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Hyman, L. Population-Based Studies in Ophthalmology. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 146, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ying, G.; Fu, X.; Zhang, R.; Meng, J.; Gu, F.; Li, J. Prevalence of myopia and vision impairment in school students in Eastern China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutta, E.P.; Proskurina, O.V.; Tarasova, N.A.; Markosyan, G.A. Analysis of risk factors that cause myopia in pre-school children and primary school students. Health Risk Anal. 2019, 2019, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Long, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q. Prevalence of myopia and associated risk factors among primary students in Chongqing: Multilevel modeling. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, H.; Yamashita, T.; Yoshihara, N.; Kii, Y.; Sakamoto, T. Association of lifestyle and body structure to ocular axial length in Japanese elementary school children. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, D.; Morgan, I.G.; Kim, E. Inverse relationship between sleep duration and myopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015, 94, e204–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Yu, J.; Xia, W.; Cai, H. Correlation of Myopia with Physical Exercise and Sleep Habits among Suburban Adolescents. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Vasudevan, B.; Fang, S.J.; Jhanji, V.; Mao, G.Y.; Han, W.; Liang, Y.B. Eye exercises of acupoints: Their impact on myopia and visual symptoms in Chinese rural children. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessesse, S.A.; Teshome, A.W. Prevalence of myopia among secondary school students in Welkite town: South-Western Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, B.N.K.; You, Q.; Zhu, M.M.; Lai, J.S.M.; Ng, A.L.K.; Wong, I.Y.H. Prevalence and associations of myopia in Hong Kong primary school students. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 64, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’bdeh, S.; Al-Khatatbeh, B. Daylighting Retrofit Methods as a Tool for Enhancing Daylight Provision in Existing Educational Spaces—A Case Study. Buildings 2019, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Integrating Acclimated Kinetic Envelopes into Sustainable Building Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2014. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/152455 (accessed on 28 May 2014).

- Beijing No. 4 High School Fangshan Campus/OPEN. Available online: https://www.gooood.cn/beijing-4-high-school-by-open.htm. (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- The School of Parallel and Light, Sichuan, China by HUA Li. Available online: https://www.gooood.cn/the-school-of-parallel-and-light-hua-li.htm (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Innovative Design. Gulide for Daylighting School. Lighting Research Center Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: America. 2004. Available online: https://www.lrc.rpi.edu/programs/daylighting/pdf/guidelines.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2004).

- Defu Junior High School, Shanghai By Atelier GOM. Available online: https://www.gooood.cn/defu-junior-high-school-by-atelier-gom.htm. (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Hongling Experimental Primary School, China by O-Office Architects. Available online: https://www.gooood.cn/hongling-experimental-primary-school-china-by-o-office-architects.htm (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- The Dalles Middle School A High Performance School. Available online: https://www.slideserve.com/ahanu/the-dalles-middle-school-a-high-performance-school-powerpoint-ppt-presentation (accessed on 28 March 2019).

- Garcia, J.M.; Trowbridge, M.J.; Huang, T.T.; Weltman, A.; Sirard, J.R. Comparison of static and dynamic school furniture on physical activity and learning in children. Med. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2014, 46, 513–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Hou, F.; Zhou, J.; Hao, L.; Mou, T.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X. Expert consensus on LED lighting in classrooms for myopia prevention and control. J. Light. Eng. 2019, 30, 36–40+46. [Google Scholar]

- Daylighting|WBDG—Whole Building Design Guide. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/daylighting (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Lanningham-Foster, L.; Foster, R.C.; McCrady, S.K.; Manohar, C.U.; Jensen, T.B.; Mitre, N.G.; Levine, J.A. Changing the School Environment to Increase Physical Activity in Children. Obesity 2008, 16, 1849–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardon, G.; De Clercq, D.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Breithecker, D. Sitting habits in elementary schoolchildren: A traditional versus a “Moving school”. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 54, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, G.; Labarque, V.; Smits, D.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Promoting physical activity at the pre-school playground: The effects of providing markings and play equipment. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiyang No. 7 Middle School and Affiliated Primary School, Guangdong/Motai Architecture. Available online: https://www.gooood.cn/huiyang-no-7-secondary-school-and-affiliated-primary-school-by-multiarch.htm (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Panter, J.R.; Jones, A.P.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Griffin, S.J. Neighborhood, Route, and School Environments and Children’s Active Commuting. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willenberg, L.J.; Ashbolt, R.; Holland, D.; Gibbs, L.; MacDougall, C.; Garrard, J.; Waters, E. Increasing school playground physical activity: A mixed methods study combining environmental measures and children’s perspectives. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraete, S.J.M.; Cardon, G.M.; De Clercq, D.L.R.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.M.M. Increasing children’s physical activity levels during recess periods in elementary schools: The effects of providing game equipment. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, E.; Torsheim, T.; Sallis, J.F.; Samdal, O. The characteristics of the outdoor school environment associated with physical activity. Health Educ. Res. 2008, 25, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso Sanchez, J.; Ikaga, T.; Vega Sanchez, S. Quantitative improvement in workplace performance through biophilic design: A pilot experiment case study. Energy Build. 2018, 177, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittin, J.; Sorensen, D.; Trowbridge, M.; Lee, K.K.; Breithecker, D.; Frerichs, L.; Huang, T. Physical Activity Design Guidelines for School Architecture. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Physical Activity and Physical Education in the School Environment. In Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, L.E.; List, D.G.; Marx, T.; May, L.; Helgerson, S.D.; Frieden, T.R. Childhood Obesity in New York City Elementary School Students. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1496–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordel, S.; Breithecker, D. Bewegte sSchule als Chance einer Rörderung der Lern- und Leistungsfähigkeit. Haltung Und Beweg. 2003, 2, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry, C.N.; Lee, S.M.; Robin, L.; Laris, B.A.; Russell, L.A.; Coyle, K.K.; Nihiser, A.J. The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance: A systematic review of the literature. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, S10–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft, D.I. Emmetropisation and the aetiology of refractive errors. Eye 2014, 28, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.-Y.; Huang, L.-H.; Schmid, K.L.; Li, C.-G.; Chen, J.-Y.; He, G.-H.; Chen, W.-Q. Associations Between Screen Exposure in Early Life and Myopia amongst Chinese Preschoolers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Zhu, J.; Zou, H.; Lu, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Q.; He, J. Analysis of hyperopia reserve as a predictor of myopia in children: A two-year follow-up study. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Ophthalmology and the Third International Conference on Orthokeratology, Shangha, China, 28 March 2014; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.Y.; Yu, W.Y.; Lam, C.H.I.; Li, Z.C.; Chin, M.P.; Lakshmanan, Y.; Chan, H.H.L. Childhood exposure to constricted living space: A possible environmental threat for myopia development. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2017, 37, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Relevant Factors | Study Setting Location | Population Characteristics | Research Aim | Research Description | Research Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| personal eye habits related myopia [13] | Guangdong province, China. | 2289 students online and 2570 students on-site | To examine the prevalence of myopia and its related personal eye habits. | Using stratified random cluster sampling with eye examinations and questionnaires | One month (July 2020) |

| light levels in classrooms [14] | Northeast of China | 317 subjects from 1713 eligible students (6–14) in four schools | To determine whether elevated light levels in classrooms in rural areas can protect visual health. | A stratified cluster sampling visual acuity (VA) test was applied three times (at baseline, 6 months and 1 year after intervention) through eye examinations and a questionnaire. | One year (2011–2012) |

| family, activity, and school factors [15] | Taiwan, China. | Taiwanese children in Grades 4–6 | To explore the effect of family, activity, and school factors on myopia risk and severity. | National cross-sectional data, bivariate and multivariate analyses | Unspecified |

| multimedia teaching material under naturally varying classroom lighting conditions [16] | Taiwan, China. | children in grades 4–6 across 87 schools | To determine whether exposure to digitally projected and multimedia teaching material under naturally varying lighting conditions is associated with visual health. | A population-based, cross-sectional study | One year |

| outdoor time, near work and parental myopia. [17] | Beijing, China. | 382 grade-1 children (age: 6.3–0.4 years) with 305 | To investigate factors associated with ocular axial elongation and myopia progression | Follow-up research and longitudinal designs | Four years follow-up |

| age, habitation, gender body mass index, body height, school type [18] | Beijing, China. | 54 schools randomly selected from 15 districts, including 35,745 samples | To assess prevalence and associated factors of myopia and high myopia in schoolchildren in Greater Beijing. | A school-based, cross-sectional investigation | In 2016 |

| parental myopia, outdoor time, near work, screen time, physical activity, and eating habits. [19] | France | 264 children aged 4 to 18 years attending the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Gui de Chauliac | To evaluate risk factors for paediatric myopia in a contemporary French cohort while takingt eating habits into account. | An epidemiological cross-sectional study | One year (May 2007–May 2008) |

| age, screen time near work distance, outdoor activity [20] | Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, | school children between 6–18 years of age in Bahir Dar city | To assess the prevalence and associated factors of myopia among school children | A school-based cross-sectional study | One month (October 2019–November 2019) |

| light exposure and physical activity levels [21] | America | 102 children (41 myopia and 61 emmetrope) aged 10–15 | To objectively assess daily light exposure and physical activity levels in children. | Using a wrist worn actiography device to measure visible light illuminance and physical activity | 2-weeks |

| gender, age, parental myopia, sitting location, near work, and outdoor activities [22] | Nantong, China | At least two classes from each grade of each school in Nantong. | To investigate the prevalence of myopia and the factors associated with it among students in Nantong. | School-based cross-sectional study; randomly selected; self-reported questionnaire | Unspecified |

| outdoor time, near work, parental myopia and gender [23] | Gongshu District of Hangzhou City, China | 1004 third-grade students | To study the prevalence and risk factors of myopia in the initial stage among primary schools, and to provide protective suggestions. | Myopia questionnaires; eyesight-related parameters | three months (November 2017–February 2018) |

| individual characteristic and eye habits; the influence of social cognition variables on myopia prevention behaviors [24] | Guangdong, China | 4894 students at 6 junior high schools in 5 prefectures of Guangdong province | To examine the prevalence of myopia and its related personal eye habits among junior high school students and to explore stage-specific myopia prevention behaviors. | stratified random cluster sampling 2 289 students online and 2 570 students on-site with questionnaire | July 2020 |

| outdoor time [25] | Canada | 166 children | To determine the prevalence of myopia, proportion of uncorrected myopia and pertinent environmental factors among children. | Refraction with cycloplegia and ocular biometry were measured in children from two age groups. Parents completed a questionnaire | One year 2014–2015 |

| long-term excessive use eye, outdoor activities and gender [26] | China | Primary students (11,246) junior students (3673) senior students (4220) | To explore the situation and the affect factors of myopia and scientificalness and effectiveness of eye exercises. | Random cluster sampling, A questionnaire was distributed | Unspecified |

| flat room, living floor and outdoor time [27] | China | 43,771 children from 12 cities | To evaluate living environment’s impact on school myopia in Chinese school-aged children. | A large cross-sectional sample of area- and ethnicity-matched school children, questionnaire | March and June 2012 |

| parents myopia, environmental factors [28] | China | 353 farmers and 162 farmer families | To quantitatively assess the role of heredity and environmental factors in myopia. The family was referred to in order to establish an environmental and genetic index. | A pedigree analysis with one child (university student), father, and mother; in a multiple regression analysis; 114 pedigree; milies were used as a control group. | Unspecified |

| near work, social-constructed gender difference on myopia [29]. | Yunnan, China | the nationally representative data of CEPS | To verify there exists a difference in myopia prevalence. | Clinical eye examination and questionnaire | In 2014 |

| school type, gender, age, parental myopia, socio-economic status, screening time [30]. | Delhi | 9884 children (66.8% boys) | To assess prevalence of myopia and identify associated risk factors in urban school children. | A cross-sectional study questionnaire | Unspecified |

| gender, age, parental myopia, socio-economic status, near work, screening time [31]. | Delhi | 10,000 school children aged 5–15 | To evaluate the incidence and progression of myopia along with the factors associated with the progression of myopia in school going children in Delhi. | Prospective longitudinal study interval screening | One year |

| sociodemographic factors, (income and education) height [32] | Korean | A total of 33,355 Koreans over a five-year period. | To evaluate the association between myopia and risk factors, including anthropometric parameters. | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data | Four years |

| homework and outdoor time [33] | Baoshan District, Shanghai, China | 842 migrant children from 2 migrant schools and 1081 from 2 local schools | To compare patterns of myopia prevalence and progression between migrant and resident children. | Random sample Baseline measurements were taken of children in grades 1–4, and children in grades 1 and 2 were followed for 2 years. | Two years |

| physical activity [34] | Danish | 307 children | To determine associations between physical activity (PA) and myopia in Danish school children and investigate the prevalence of myopia. | A prospective study with longitudinal data. PA was measured objectively by repeated ActiGraph accelerometer measurement four times with different intervals (1–2.5 years). | in 2015 (7-years follow-up) |

| living area, age, gender, sleep duration, and outdoor time [35]. | Shanghai, China | 6295 school-aged children | To offer new insights to future myopia aetiology studies as well as aiding the decision-making of myopia prevention strategies. | Follow-up study with eye examination. | Two-years |

| near work and outdoor activities [36] | Handan rural, China | 572 (65.1%) of 878 children (6–18 years of age) | To evaluate the relationship of both near work and outdoor activities with refractive error in rural children in China. | Cross-sectional study Handan Offspring Myopia Study (HOMS). | Three months (March 2010–June 2010) |

| parental myopia, age and household income [37] | Korean | 3862 children from 5–18 years of age from 2344 families | to investigate the effect of parental refractive errors on myopic children in Korean families | The ophthalmologic examination dataset of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys IV and V. | Four years (2008–2012) |

| content and time of near work, screening time and desk light [38] | Anyang, China | 770 grade 7 students with mean age of 12.7 years | To examine the associations of near work related parameters with spherical equivalent refraction and axial length. | Examined with cycloplegic autorefraction and axial length. | Two months (October 2011–December 2011) |

| Chinese cities location (linked to light exposure), education level, and gender [39] | Northern and Southern China | 9171 primary school students (grades from 1 to 6) | To assess the myopia prevalence rate and evaluate the effect of sunshine duration on myopia. | This prospective cross-sectional study National Geomatics Center of China (NGCC) and China Meteorological Administration provided data | Two months (October 2019–November 2019). |

| age, parental myopia, BMI (Body Mass Index) [40] | South Korea. | 983 children 5–18 years of age | To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors associated with myopia and high myopia in children in South Korea. | Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2016–2017 (KNHANES VII) data | Unspecified |

| Chinese eye exercises [41] | Anyang, China | Eligible 201 of 260 children at baseline | To investigate Chinese eye exercises and factors associated with the development of myopia. | Case-control study | Two years (September 2011–November 2013). |

| higher degree of education (such as attendance of schools, and time spent for indoors versus outdoor time) [42] | Beijing and Shandong, China; India, | 3468 adults;(mean age:64.6 ± 9.8 years; range: 50–93 years) | To examine if education-related parameters differ between high myopia in today’s school children and high pathological myopia in the contemporary elderly generation. | The population-based Beijing Eye Study and Central India Eye and Medical Study, and the children and teenager populations of the Shandong Children Eye Study, Gobi Desert Children Eye Study, Beijing Pediatric Eye Study, Beijing Children Eye Study, Beijing High School Teenager Eye Study | Unspecified |

| outdoor activities [43] | both urban and rural Northeast, China | 3051 students of two primary and two junior high schools | To test the impact on myopia development of a school-based intervention program aimed at increasing outdoors time. | Case-control study self-questionnaire and parents questionnaire | One-year |

| sociodemographic, environmental factors, regional environment differences [44] | Sydney | 2367 children and their parents. | To examine associations between myopia and measures of urbanization in a population-based sample of 12-year-old Australian children. | Questionnaire data on sociodemographic and environmental factors from 2367 children (75.0% response) and their parents. | Two years (2003–2005) |

| age, parental myopia, the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration, near work and inflammation reflected by white blood cells counts [45] | Korea | 3398 subjects aged 19–49 | To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of myopia in adult Korean population. | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2014 (KNHANES VI). Data | Unspecified |

| outdoor time and time spent indoors [46] | Beijing, China | 643 returned for follow-up examination of 681 students | To assess whether a change in myopia related oculometric parameters was associated with indoors and outdoors activity. | One-year follow-up the longitudinal school-based study | one-year |

| gender, grade, near work and parental myopia [47] | Guangzhou, China | 3055 students of grades 1–6 and grades 7–9 | To estimate the prevalence of myopia and to explore the factors that potentially contribute to myopia. | Refractive error measurements and a structured questionnaire data | In December 2014 |

| environment, time of near work, heredity, nationality, grade, and outdoor time [48] | Guizhou, China | 7272 qualified students of 8413 students | To investigate the prevalence of myopia among urban and rural students in the Xingyi city of Guizhou province and to analyze the influencing factors. | Visual acuity, refractive examination, were examined among all the subjects, and a questionnaire was analyzed by using logistic regression. | Three months (August 2019–November 2019) |

| genetics, gender, education, parental myopia, onset age of myopia, outdoor activities, vision care knowledge [49] | Taiwan, China | 522 schoolchildren with myopia | To understand the risk factors for its development and progression and to identify if they are important to public health. | Observational studies self-questionnaire | Nine months (February 2018–November 2018) |

| sleep quality [50] | Tokyo, Japan. | 486 participants aged from 10–59 | To evaluate sleep quality in myopic children and adults. | The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire | Three months (January 2014 –March2014) |

| parental myopia, near work time and outdoor time [51] | Aba, Nigeria. | 1197 (male: 538 and female: 659) children 8 and 15 years | To assess the influence of near work, time outdoor and parental myopia on the prevalence of myopia | Myopia risk factor questionnaire cycloplegic refraction | Unspecified |

| Research Relevant Factors | Study Setting, Location | Study | Number of Studies Reviewed | Main Findings | Method of Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| environmental factors [8] (p. 2) | Singapore | Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia | 53 | The precise biological mechanisms through which the environment influences ocular refraction are a matter of debate. Outdoors time is an important factor in the prevention of myopia. | Systematic review, meta-analysis |

| exposure to outdoor ambient daylight [52] | Indian | Increasing time in outdoor environment could counteract the rising prevalence of myopia in Indian school-going children | 29 | The article describes the current myopia scenario in India; identifies ways to tackle the future epidemic. It considers the importance of day light exposure in counteracting myopia and reported possible public health policies for initiation at a school level that could potentially help in myopia prevention and control its progression. | Narrative review |

| ow-concentration atropine and outdoor time [53] | America | Myopia Control: A Review | 53 | Antimuscarinic agents include pirenzepine and atropine, low-concentration atropine and outdoor time have been shown to reduce the likelihood of myopia onset. | Narrative review |

| educational pressure(read for long hours), outdoor time, low-dose atropine and orthokeratology [3] | Asia | Stopping the rise of myopia in Asia | 160 | More time outdoors and low-dose atropine show best effect in reducing the incidence of myopia and delaying its the onset. Low-dose atropine, orthokeratology, executive prismatic bifocals, and multifocal soft contact lenses have been shown to be remarkably effective in slowing myopia progression. | Narrative review |

| near work activity, environmental factors, markers for myopia in the human genome [54] | Singapore | Myopia: gene-environment interaction | Unspecified | Both genes and environmental factors may be related to myopia. There are no conclusive studies at present, however, that identify the nature and extent of possible gene-environment interaction. | Narrative review |

| light intensity outdoors, the chromaticity of daylight or vitamin D levels. [55] | Singapore | A review of environmental risk factors for myopia during early life, childhood and adolescence | 72 | Population-based data show a consistent protective association between time outdoors and myopia. Evidence for the association of near work with myopia is not as robust as time outdoors and may be difficult to quantify. | Narrative review |

| educational environment [56] | China | Educational Environment: The Most Powerful Factor for the Onset and Development of Myopia among Students | 35 | The study identifies the education environment as the primary factor that causes the onset and progression of student myopia, the paper fully recognizes the scientific rationality of and the specific role served by education-medicine synergy in student myopia prevention and control. | Narrative review |

| near work (time and intensity) and myopia, and its possible mechanisms [10] (p. 2) | China | Relationship between near work and the development of myopia in adolescents | Unspecified | The article summarizes the epidemiological studies on the relationship between near work content, total time spent on near work, intensity of near work and myopia, and its possible mechanisms, and does so with the aim of providing a point of provide reference for myopia epidemiology and etiology. | Narrative review |

| light environment(electronic light) [57] | Japan | Progress and Control of Myopia by Light Environments | 50 | Until the ideal pharmacological targets are found, manipulating light environment is the most practical way to prevent myopia. Approximately 2 h of outdoor light exposure per day is recommended. | Narrative review |

| natural light [58] | Switzerland | Pandemic of childhood myopia. Could new indoor led lighting be part of the solution? | 82 | Heritability is one of the factors most linked with young myopia together with increased near-distance work, however, there is no evidence that children inherit a myopathic environment or a susceptibility to the effects of near-distance work performed from their parents. | Systematic review |

| outdoor time [59] | Shanghai, China | Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review | 51 | To evaluate the evidence for association between outdoor time and (1) risk of onset of myopia (incident/prevalent myopia); (2) risk of a myopic shift in refractive error and (3) risk of progression in myopia. | Systematic review |

| relationship between gene-environment interaction and myopia [60] | Nanjing, China. | Gene-environment Interaction in Spherical Equivalent and Myopia: An Evidence-based Review | Unspecified | To systematically research association between gene-environment interaction and the myopia/spherical equivalent. | Narrative review |

| genetic and environmental factors [61] | Denmark | Genetic and environmental effects on myopia development and progression | 33 | To summarize the relationship between gene-environment interaction and myopia; and to find the interaction effect of the gene or genetic risk score with the environment. | Narrative review |

| parental myopia, ethnic differences, outdoor time, near work, population density and socioeconomic status [6] (p. 2). | Poland | A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide | 55 | To review the current literature on epidemiology and risk factors for myopia in school children (aged 6–19 years) around the world. | Systematic review |

| Design Domains | Strategies | Relevant Literature | Evidence Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Provide precise and controllable environment of visual operation behavior | |||

| Control the stability of the daylight environment | |||

| Using the windows construction technology | [114,115] [116,117] | ★ | |

| Considering the school’s layout to maximize the internal visual daylighting | [118] [119,120] | ★ | |

| Using the teaching unit’ s internal structure measures | [121] [122,123] | ✰ | |

| Account for site constraints and benefits to optimize the internal visual daylighting | [123,124] | ✰ | |

| Enhance the comfort of the mixed light environment | |||

| Arranged light fixtures in accordance with teaching type and the requirement of multimedia screen cooperation | [14] (p. 5) | ✰ | |

| Design artificial illumination parameters in accordance with the variation trend of daylight in different climacteric areas | [14] (p. 5), [61] (p. 12) | ★ | |

| Consider the photobiological safety of the display screen | [33] (p. 8) | ✰ | |

| Consider the Healthy Circadian Lighting on the basis of the non-visual effects of daylighting | [102] (p. 17) | ✰ | |

| Enhance the resilience of the visual background environment | |||

| Consider the indoor environment factors’ design, | [27] (p. 7) [124] | ✰ | |

| |||

| Combine daylight and the external landscape to utilize view window to provide visual connection to the outdoors | [122] | ○ | |

| Improve environmental adaptability for visual work tasks | |||

| Optimize the scale of teaching unit according to the light spatial distribution and visual distance of multimedia teaching | [122,123] | ✰ | |

| Consider the sharpness requirement of the multimedia display screen | [16] (p. 5) | ✰ | |

| The internal configuration of teaching unit space adapts to the update of education mode | [32,96,125,126] (p. 8) | ★ | |

| 2 Active design for environment of outdoor exposure behavior | |||

| Enhance the interactivity of the outdoor environment | |||

| Enhance the diversification and interesting of areas near classroom | [127] [128] | ✰ | |

| Enhance the diversification and interesting of activity areas | [117,129] [122] | ✰ ✰ | |

| Consider the merging of different spatial levels to enhance openness and transparency | [121] | ○ | |

| Enhance the accessibility of outdoor spaces | |||

| Improve the land utilization of school design to improve outdoor activity needs’ configuration | [130] [124] | ✰ | |

| Provide convenient access for minors to outdoor areas to optimize accessibility | [131] [122] | ★ | |

| Consider the influence of school location on minors’ public transportation access | [129] | ✰ | |

| Improve the diversity of outdoor functions | |||

| Consider diversified school outdoor spaces design | [117,121] | ✰ | |

| Consider minors’ preference to decorate outdoor activity areas | [132] [117] | ★ | |

| Improve the adaptability of outdoor facilities | |||

| Consider indoor and outdoor activity places to suit minors’ age and behavior patterns | [117] | ○ | |

| Make interactive landscape experiences more themed and flat | [117] | ○ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, H.; Bai, X. A Review of the Role of the School Spatial Environment in Promoting the Visual Health of Minors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021006

Zhou H, Bai X. A Review of the Role of the School Spatial Environment in Promoting the Visual Health of Minors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021006

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Huihui, and Xiaoxia Bai. 2023. "A Review of the Role of the School Spatial Environment in Promoting the Visual Health of Minors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021006

APA StyleZhou, H., & Bai, X. (2023). A Review of the Role of the School Spatial Environment in Promoting the Visual Health of Minors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021006