Responding to the HIV Health Literacy Needs of Clients in Substance Use Treatment: The Role of Universal PrEP Education in HIV Health and Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. HIV Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of HIV Health and Prevention

3. Overview of PrEP for Substance Use Counselors

4. Barriers to PrEP Use and Education

4.1. Lack of HIV Health Literacy

Personal HIV Health Literacy

4.2. Organizational HIV Health Literacy

4.3. Financial Barriers

4.4. Geographical Barriers

4.5. Housing Instability

4.6. Stigma

5. Recommendations for Clinical Practice to Deliver PrEP Education and Implementation within a Trauma-Informed Framework

5.1. A Trauma-Informed Universal PrEP Education Framework

5.2. Integrating Universal PrEP Education within Trauma-Informed Care

5.3. Facilitating PrEP Access

5.4. Preparing Clients for PrEP Referral

5.4.1. Long-Acting Injectable vs. Daily Oral PrEP

5.4.2. Same-Day PrEP Prescription

5.5. Encouraging PrEP Uptake and Adherence

6. Directions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

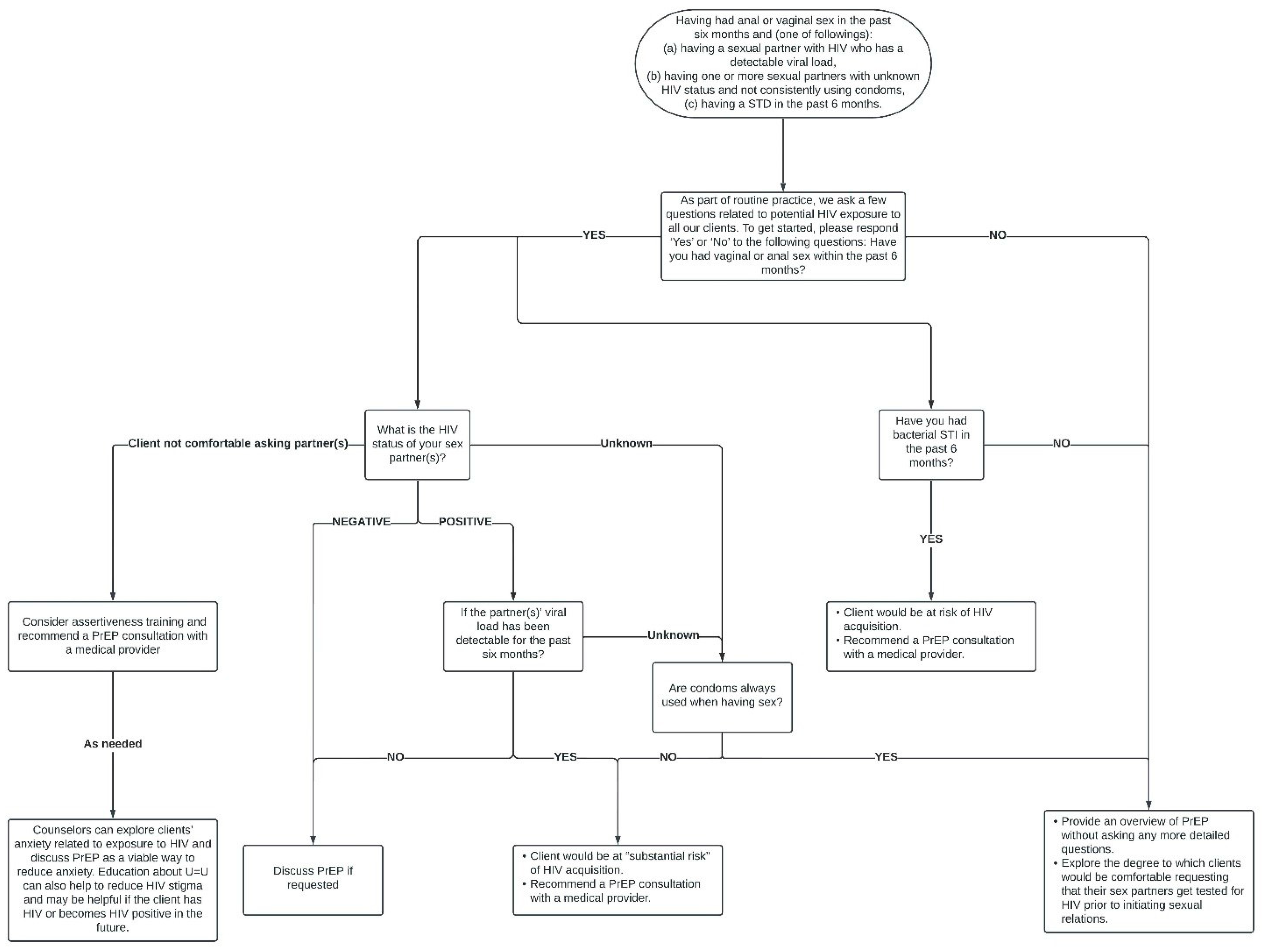

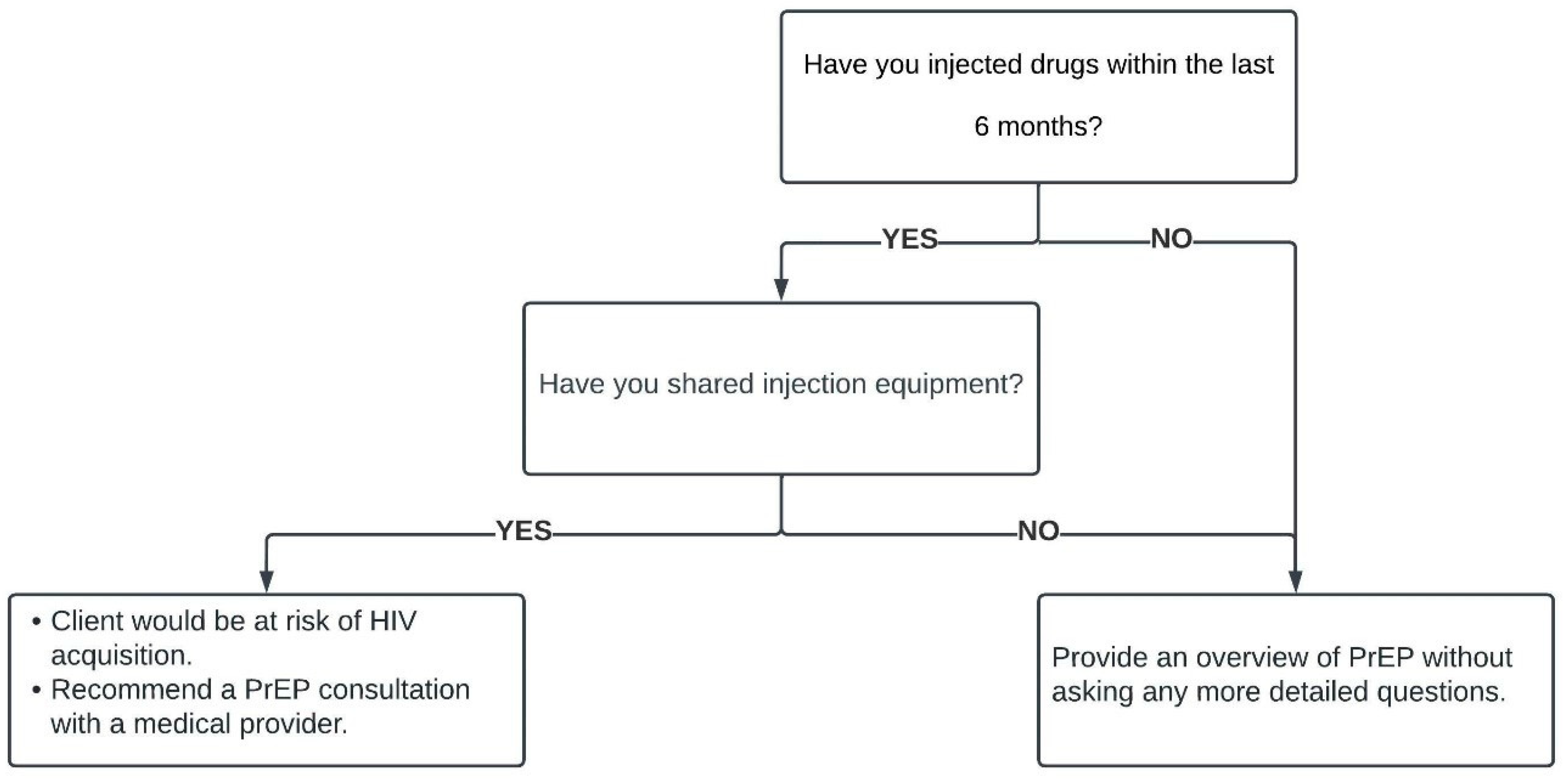

Appendix A. Brief Assessment Recommended by the Latest PrEP Guidelines

References

- Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Nutbeam, D.; Lloyd, J.E. Understanding and Responding to Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, J.; Harrison, D. Funding PrEP for HIV Prevention. BMJ 2016, 354, i3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, S.M.; Reilly, K.H.; Neaigus, A.; Braunstein, S. Awareness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among Women Who Inject Drugs in Nyc: The Importance of Networks and Syringe Exchange Programs for HIV Prevention. Harm Reduct. J. 2017, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshak, T.B.; Parker, L.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Isadore, K.M.; Zhai, Y.; Banerjee, R.; Conyers, L.M. Addressing the Syndemic Effects of Incarceration: The Role of Rehabilitation Counselors in Public Health. Rehabil. Res. Policy Educ. 2022, 36, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M. A Dose of Drugs, a Touch of Violence, a Case of Aids: Conceptualizing the Sava Syndemic. Free Inq. Creat. Sociol. 2000, 28, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- US Public Health Service: Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2021 Update: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- National HIV/Aids Strategy for the United States 2022–2025. Available online: https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/NHAS-2022-2025.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Tip 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-02-01-002.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Reynolds, R.; Smoller, S.; Allen, A.; Nicholas, P.K. Health Literacy and Health Outcomes in Persons Living with HIV Disease: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 3024–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Wosinski, J. Does Health Literacy Mediate the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Health Disparities? Integrative Review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Health Literacy? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Sullivan, P.S.; Mena, L.; Elopre, L.; Siegler, A.J. Implementation Strategies to Increase PrEP Uptake in the South. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tross, S.; Spector, A.Y.; Ertl, M.M.; Berg, H.; Turrigiano, E.; Hoffman, S. A Qualitative Study of Barriers and Facilitators of PrEP Uptake among Women in Substance Use Treatment and Syringe Service Programs. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.H.; Agwu, A.; Malebranche, D. Barriers to the Wider Use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in the United States: A Narrative Review. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 1778–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, A.Y.; Remien, R.H.; Tross, S. PrEP in Substance Abuse Treatment: A Qualitative Study of Treatment Provider Perspectives. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2015, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.K.; Herbst, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Rose, C.E. Condom Effectiveness for HIV Prevention by Consistency of Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.; Roepke, A.; Wardell, E.; Teitelman, A.M. Do You PrEP? A Review of Primary Care Provider Knowledge of PrEP and Attitudes on Prescribing PrEP. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2018, 29, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.T.; O’Rourke, A.; White, R.H.; Smith, K.C.; Weir, B.; Lucas, G.M.; Sherman, S.G.; Grieb, S.M. Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Use among People Who Inject Drugs in Rural Appalachia: A Qualitative Study. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 1942–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.M.; Dillon, F.R.; Babino, R.; Melton, J.; Spadola, C.; Da Silva, N.; De La Rosa, M. Recruiting and Assessing Recent Young Adult Latina Immigrants in Health Disparities Research. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2016, 44, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, G.S.; Crawford, F.W. Dynamics of the HIV Outbreak and Response in Scott County, in, USA, 2011–15: A Modelling Study. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e569–e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Advisory Committee Blood (Arbeitskreis Blut). Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2016, 43, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIV Life Cycle. Available online: https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/infographics/hiv-life-cycle (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Hosek, S.G.; Rudy, B.; Landovitz, R.; Kapogiannis, B.; Siberry, G.; Rutledge, B.; Liu, N.; Brothers, J.; Mulligan, K.; Zimet, G.; et al. An HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project and Safety Study for Young Msm. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017, 74, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.S.; Woodyatt, C.; Koski, C.; Pembleton, E.; McGuinness, P.; Taussig, J.; Ricca, A.; Luisi, N.; Mokotoff, E.; Benbow, N.; et al. A Data Visualization and Dissemination Resource to Support HIV Prevention and Care at the Local Level: Analysis and Uses of the Aidsvu Public Data Resource. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, K.M.; Peters, H.C. Queer Adolescents Dating and Sexuality: Implications for Counselors, Counselor Educators, and Supervisors. J. Child Adolesc. Couns. 2019, 5, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.E.; Paton, M.; Muessig, K.E.; Vecchio, A.C.; Hanson, L.A.; Hightow-Weidman, L.B. “Do I Want PrEP or Do I Want a Roof?”: Social Determinants of Health and HIV Prevention in the Southern United States. AIDS Care 2022, 34, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, M.; Hirsch-Moverman, Y.; Franks, J.; Hayes-Larson, E.; El-Sadr, W.M.; Mannheimer, S. Limited Awareness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in New York City. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, K.L.; Colarossi, L.G.; Sanders, K. Raising Awareness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among Women in New York City: Community and Provider Perspectives. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlayson, T.; Cha, S.; Xia, M.; Trujillo, L.; Denson, D.; Prejean, J.; Kanny, D.; Wejnert, C.; National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group. Changes in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men—20 Urban Areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.S.; Goparaju, L.; Sales, J.M.; Mehta, C.C.; Blackstock, O.J.; Seidman, D.; Ofotokun, I.; Kempf, M.-C.; Fischl, M.A.; Golub, E.T.; et al. Brief Report: PrEP Eligibility among at-Risk Women in the Southern United States: Associated Factors, Awareness, and Acceptability. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2019, 80, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowniak, S.; Ong-Flaherty, C.; Selix, N.; Kowell, N. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Barriers to PrEP among Trans Men. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2017, 29, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.; Hubach, R.D.; Williams, D.; Voorheis, E.; Lester, J.; Reece, M.; Dodge, B. Facilitators and Barriers of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake among Rural Men Who Have Sex with Men Living in the Midwestern U.S. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.S.; Stringer, K.L.; Sohail, M.; Crockett, K.B.; Atkins, G.C.; Kudroff, K.; Batey, D.S.; Hicks, J.; Turan, J.M.; Mugavero, M.J.; et al. Accessing Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Perceptions of Current and Potential PrEP Users in Birmingham, Alabama. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2966–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, J.; Chen, R.; Huber, C.; Parascando, J.; Nunez, J. Primary Care Provider HIV PrEP Knowledge, Attitudes, and Prescribing Habits: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Late Adopters in Rural and Suburban Practice. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 215013192211472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.M.; Witte, S.S.; Filippone, P.; Choi, C.J.; Wall, M. Interprofessional Collaboration and on-the-Job Training Improve Access to HIV Testing, HIV Primary Care, and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS Educ. Prev. 2018, 30, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilan, A.M.; Landovitz, R.J.; Le, M.H.; Grinsztejn, B.; Freedberg, K.A.; McCauley, M.; Wattananimitgul, N.; Cohen, M.S.; Ciaranello, A.L.; Clement, M.E.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Long-Acting Injectable HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in the United States: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousseine, Y.M.; Allaire, C.; Ringa, V.; Lydie, N.; Velter, A. Health Literacy as a Mediator of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Position and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Uptake among Men Who Have Sex with Men Living in France. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2023, 7, e61–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- People Who Reported as Both Black and White More Than Doubled. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn185.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Touger, R.; Wood, B.R. A Review of Telehealth Innovations for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Maria, D.; Flash, C.A.; Narendorf, S.; Barman-Adhikari, A.; Petering, R.; Hsu, H.-T.; Shelton, J.; Bender, K.; Ferguson, K. Knowledge and Attitudes About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Young Adults Experiencing Homelessness in Seven U.S. Cities. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.L.; Rhoades, H.; Harris, T.; Winetrobe, H.; Rice, E.; Henwood, B. Risk Behavior and Access to HIV/Aids Prevention Services in a Community Sample of Homeless Persons Entering Permanent Supportive Housing. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.J.; Dunn, M.; Huff, J. Examining Health Literacy Levels in Homeless Persons and Vulnerably Housed Persons with Mental Health Disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.; Linn, C.; Nace, E.; Gelberg, L.; Cowan, B.; Fulcher, J.A. Implementation of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Homeless Primary Care Setting at the Veterans Affairs. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 215013272090837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.J.; Anderson, K.M.; Mayer, L.; Kuhn, T.; Klein, C.H. Findings from Formative Research to Develop a Strength-Based HIV Prevention and Sexual Health Promotion Mhealth Intervention for Transgender Women. Transgender Health 2019, 4, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, L.A.; Driffin, D.D.; Kegler, C.; Smith, H.; Conway-Washington, C.; White, D.; Cherry, C. The Role of Stigma and Medical Mistrust in the Routine Health Care Engagement of Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e75–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Why Do They Help People with Aids/HIV Online? Altruistic Motivation and Moral Identity. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2020, 46, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, P.L.; Mills, K.L.; Barrett, E.; Back, S.E.; Teesson, M.; Baker, A.; Sannibale, C.; Hopwood, S.; Merz, S.; Rosenfeld, J.; et al. Childhood Trauma among Individuals with Co-Morbid Substance Use and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Ment. Health Subst. Use 2011, 4, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, D.A.; Wells, E.A.; Jiang, H.; Suarez-Morales, L.; Campbell, A.N.C.; Cohen, L.R.; Miele, G.M.; Killeen, T.; Brigham, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Multisite Randomized Trial of Behavioral Interventions for Women with Co-Occurring Ptsd and Substance Use Disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crepaz, N.; Tungol-Ashmon, M.V.; Vosburgh, H.W.; Baack, B.N.; Mullins, M.M. Are Couple-Based Interventions More Effective Than Interventions Delivered to Individuals in Promoting HIV Protective Behaviors? A Meta-Analysis. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher-Borne, M.; Cain, J.M.; Martin, S.L. From Mastery to Accountability: Cultural Humility as an Alternative to Cultural Competence. Soc. Work. Educ. 2015, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayton, S.G.; Pavlicova, M.; Tamir, H.; Karim, Q.A. Development of a Prognostic Tool Exploring Female Adolescent Risk for HIV Prevention and PrEP in Rural South Africa, a Generalised Epidemic Setting. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2020, 96, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottie, K.; Medu, O.; Welch, V.; Dahal, G.P.; Tyndall, M.; Rader, T.; Wells, G. Effect of Rapid HIV Testing on HIV Incidence and Services in Populations at High Risk for HIV Exposure: An Equity-Focused Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffus, W.A.; Barragan, M.; Metsch, L.; Krawczyk, C.S.; Loughlin, A.M.; Gardner, L.I.; Mahoney, P.A.; Dickinson, G.; Rio, C.D.; Antiretroviral Treatment and Access Studies Study Group. Effect of Physician Specialty on Counseling Practices and Medical Referral Patterns among Physicians Caring for Disadvantaged Human Immunodeficiency Virus—Infected Populations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kurth, A.E.; Holmes, K.K.; Hawkins, R.; Golden, M.R. A National Survey of Clinic Sexual Histories for Sexually Transmitted Infection and HIV Screening. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2005, 32, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton Laws, M.; Bradshaw, Y.S.; Safren, S.A.; Beach, M.C.; Lee, Y.; Rogers, W.; Wilson, I.B. Discussion of Sexual Risk Behavior in HIV Care Is Infrequent and Appears Ineffectual: A Mixed Methods Study. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Metsch, L.R.; Pereyra, M.; Del Rio, C.; Gardner, L.; Duffus, W.A.; Dickinson, G.; Kerndt, P.; Anderson-Mahoney, P.; Strathdee, S.A.; Greenberg, A.E. Delivery of HIV Prevention Counseling by Physicians at HIV Medical Care Settings in 4 Us Cities. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, Y.H.; Hogben, M.; Moore-Ruffin, J.; Moore, S.E.; Fry-Johnson, Y. Sexual History-Taking among Primary Care Physicians. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2006, 98, 1924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Storholm, E.D.; Volk, J.E.; Marcus, J.L.; Silverberg, M.J.; Satre, D.D. Risk Perception, Sexual Behaviors, and PrEP Adherence among Substance-Using Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudler, A.; Cournos, F.; Arnold, E.; Koester, K.; Riano, N.S.; Dilley, J.; Liu, A.; Mangurian, C. The Case for Prescribing PrEP in Community Mental Health Settings. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e237–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killelea, A.; Johnson, J.; Dangerfield, D.T.; Beyrer, C.; McGough, M.; McIntyre, J.; Gee, R.E.; Ballreich, J.; Conti, R.; Horn, T.; et al. Financing and Delivering Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to End the HIV Epidemic. J. Law Med. Ethics 2022, 50, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On-Demand PrEP. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep/on-demand-prep.html (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Framework for Fda’s Real-World Evidence Program; The U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.S.; Carney, J.V.; Hazler, R.J. Policy Effects of the Expansion of Telehealth under 1135 Waivers on Intentions to Seek Counseling Services: Difference-in-Difference (Did) Analysis. J. Couns. Dev. 2023, 101, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIV Treatment as Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Weller, S.C.; Davis-Beaty, K. Condom Effectiveness in Reducing Heterosexual HIV Transmission. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 2012, CD003255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, M.; Herbenick, D.; Schick, V.; Sanders, S.A.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. Condom Use Rates in a National Probability Sample of Males and Females Ages 14 to 94 in the United States. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, T.A.; Tian, L.H.; Warner, L.; Satterwhite, C.L.; Metcalf, C.A.; Malotte, K.C.; Paul, S.M.; Douglas, J.M.; The RESPECT-2 Study Group. Condom Use in the Year Following a Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic Visit. Int. J. STD AIDS 2009, 20, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.K.; Pals, S.L.; Herbst, J.H.; Shinde, S.; Carey, J.W. Development of a Clinical Screening Index Predictive of Incident HIV Infection among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 60, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.S.; McCauley, M.; Gamble, T.R. HIV Treatment as Prevention and Hptn 052:. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2012, 7, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroll, A.E.; Walsh, J.L.; Owczarzak, J.L.; McAuliffe, T.L.; Bogart, L.M.; Kelly, J.A. PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among Us Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.; Zhou, G.; Li, X. Disclosure of Same-Sex Behaviors to Health-Care Providers and Uptake of HIV Testing for Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Cooper, H.L.F.; Del Rio, C.; Sanchez, T.H.; Salazar, L.F.; Sullivan, P.S. Racial Differences in the Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Atlanta, Ga. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 138, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhai, Y.; Isadore, K.M.; Parker, L.; Sandberg, J. Responding to the HIV Health Literacy Needs of Clients in Substance Use Treatment: The Role of Universal PrEP Education in HIV Health and Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196893

Zhai Y, Isadore KM, Parker L, Sandberg J. Responding to the HIV Health Literacy Needs of Clients in Substance Use Treatment: The Role of Universal PrEP Education in HIV Health and Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196893

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Yusen, Kyesha M. Isadore, Lauren Parker, and Jeremy Sandberg. 2023. "Responding to the HIV Health Literacy Needs of Clients in Substance Use Treatment: The Role of Universal PrEP Education in HIV Health and Prevention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196893

APA StyleZhai, Y., Isadore, K. M., Parker, L., & Sandberg, J. (2023). Responding to the HIV Health Literacy Needs of Clients in Substance Use Treatment: The Role of Universal PrEP Education in HIV Health and Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196893