Preventing Perinatal Depression: Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Course in Kenya and Tanzania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Mothers and Babies Course: History and Background

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Planning Phase

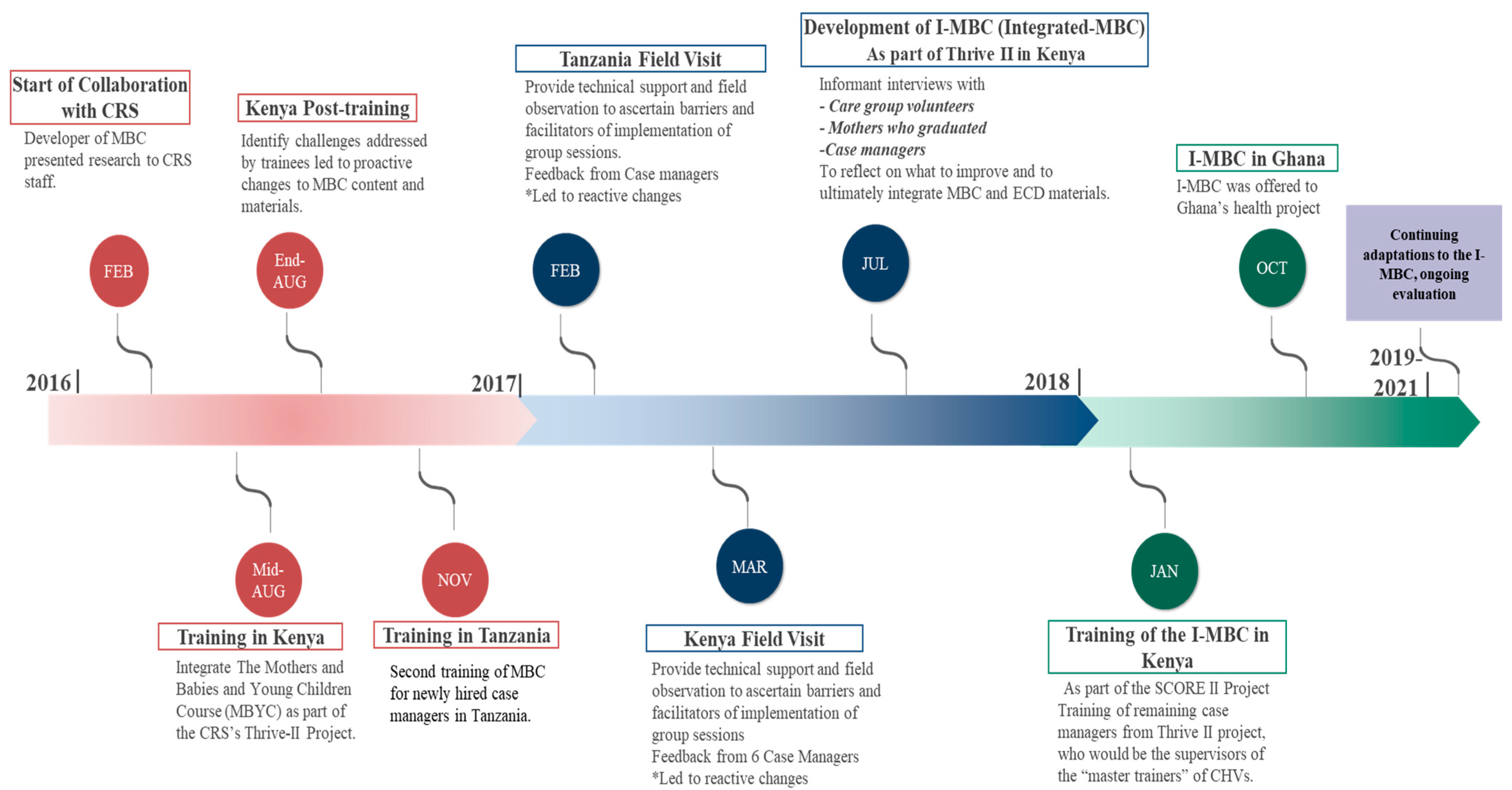

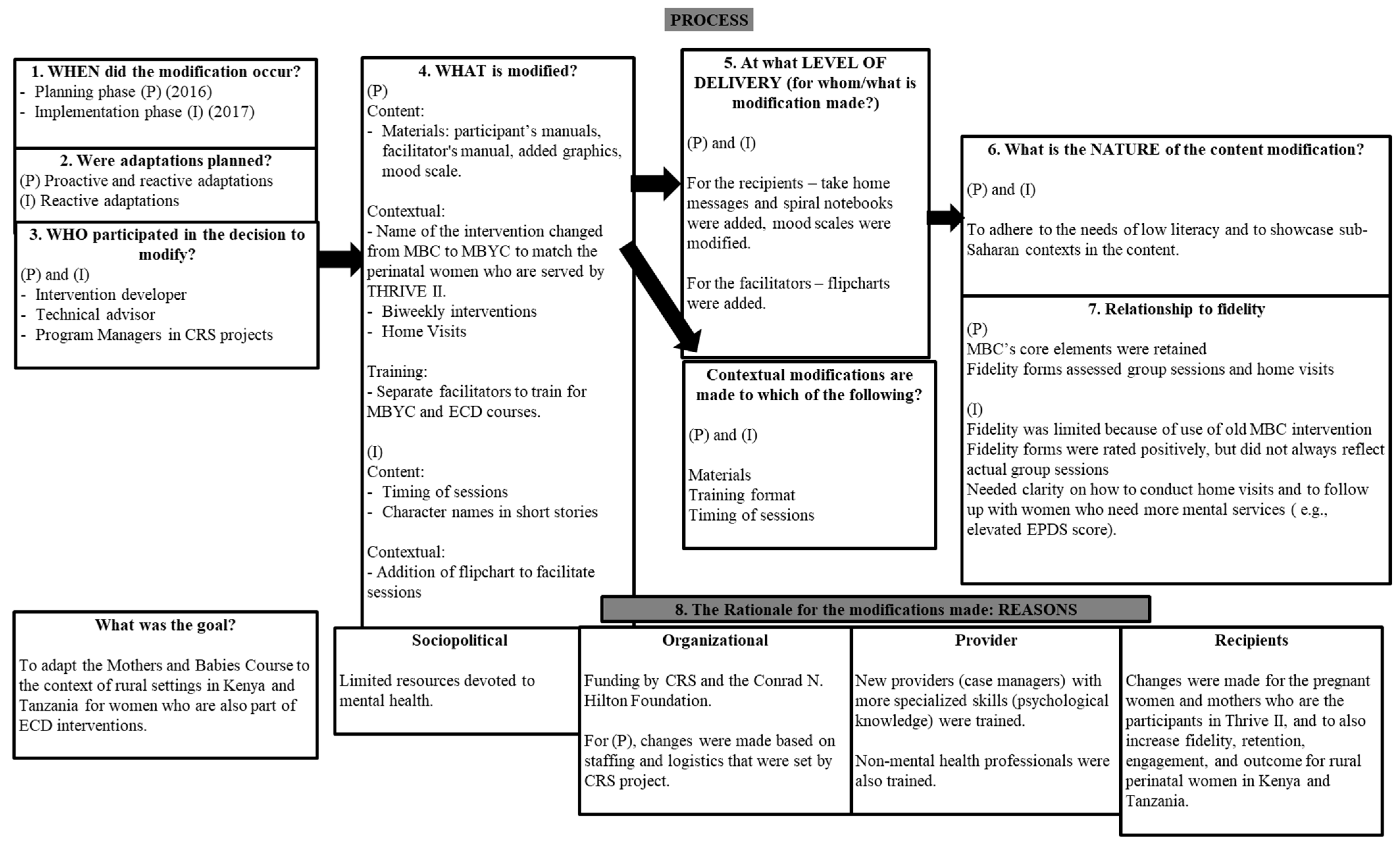

3.1.1. Aspect 1: Modifications: When and How

3.1.2. Aspects 2–6: Detailed Modifications

3.1.3. Aspect 7: Fidelity

3.1.4. Aspect 8: The Rationale for Modifications

3.2. Implementation Phase

3.2.1. Aspect 1. Modifications: When and How

3.2.2. Aspects 2–6: Detailed Modifications

3.2.3. Aspect 7: Fidelity

3.2.4. Aspect 8: The Rationale for Modifications

3.2.5. Field Visits during Implementation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dadi, A.F.; Miller, E.R.; Bisetegn, T.A.; Mwanri, L. Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.-N.; Rabemananjara, K.; Goyal, D. Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions for Mental Health Conditions among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy by Disorder; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Atuhaire, C.; Rukundo, G.Z.; Nambozi, G.; Ngonzi, J.; Atwine, D.; Cumber, S.N.; Brennaman, L. Prevalence of postpartum depression and associated factors among women in Mbarara and Rwampara Districts of South-Western Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittkowski, A.; Gardner, P.; Bunton, P.; Edge, D. Culturally determined risk factors for postnatal depression in Sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed method systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 163, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelaye, B.; Rondon, M.B.; Araya, R.; Williams, M.A. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, N.; Sikander, S.; Atif, N.; Singh, N.; Ahmad, I.; Fuhr, D.C.; Rahman, A.; Patel, V. The content and delivery of psychological interventions for perinatal depression by non-specialist health workers in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 28, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futterman, D.; Shea, J.; Besser, M.J.; Stafford, S.W.; Desmond, K.A.; Comulada, W.S.; Greco, E. Mamekhaya: A Pilot Study Combining a Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention and Mentor Mothers with PMTCT Services in South Africa. Aids Care-Psychol. Socio-Med. Asp. Aids/Hiv 2010, 22, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirman, S.W.; Baumann, A.A.; Miller, C.J. The FRAME: An expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-Based Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.; Leino, A. Advancement in the Maturing Science of Cultural Adaptations of Evidence-Based Interventions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.-N.; Perry, D.F.; Mendelson, T.; Tandon, S.D.; Muñoz, R.F. Preventing Perinatal Depression in High Risk Women: Moving the Mothers and Babies Course from Clinical Trials to Community Implementation. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.-N.; Perry, D.F.; Stuart, E.A. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Preventive Intervention for Perinatal Depression in High-Risk Latinas. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, R.F.; Le, H.-N.; Barrera, A.Z.; Pineda, B.S. Leading the Charge toward a World without Depression: Perinatal Depression Can Be Prevented. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry, S.J.; Krist, A.H. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. 2019, 105, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Second Edition: Basics and Beyond; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sockol, L.E. A Systematic Review of the Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Treating and Preventing Perinatal Depression. J. Affect. Dis. 2015, 177, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Wall, S.; Waters, E. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, C.L.; Abrams, E.T.; Klima, C.S.; Kaponda, C.P.N.; Leshabari, S.; Vonderheid, S.C.; Kamanga, M.; Norr, K.F. CenteringPregnancy-Africa: A Pilot of Group Antenatal Care to Address Millennium Development Goals. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, E. Thrive Final Program Report; Catholic Relief Services: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Docrat, S.; Besada, D.; Cleary, S.; Daviaud, E.; Lund, C. Mental Health System Costs, Resources and Constraints in South Africa: A National Survey. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.-N.; Zmuda, J.H.; Perry, D.F.; Muñoz, R.F. Transforming an Evidence-Based Intervention to Prevent Perinatal Depression for Low-Income Latina Immigrants. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, E.A.; Dogs, E.I.C.-T.; Gier, E.; Littlefield, L.; Tandon, D. Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Intervention for Use in Tribal Communities. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamil, J.; Gier, E.; Garfield, C.F.; Tandon, D. The Development and Pilot of a Technology-Based Intervention in the United States for Father’s Mental Health in the Perinatal Period. Am. J. Men’s Health 2021, 15, 155798832110443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangu, E.; Sands, N.; Rolley, J.X.; Ndetei, D.M.; Mansouri, F. Mental Healthcare in Kenya: Exploring Optimal Conditions for Capacity Building. Afr. J. Prim Health Care Fam. Med. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| FRAME Aspects | Planning Phase | Implementation Phase |

|---|---|---|

| 1. When and how in the implementation process; the modification was made | Collaboration between the intervention developer and senior technical advisor from CRS started in 2016 to add MBC to Thrive II to respond to maternal mental health needs and counseling. The intervention followed the Care Group Model as set by the ECD projects as well as home visits to check in monthly with participants. | Field visits by the intervention developer, two program managers, and the senior technical advisor were done to observe case managers implementing the intervention in Tanzania (February) and Kenya (March), 2017. Changes to the implementation process occurred thereafter. |

| 2. Whether the modification was planned/proactive or unplanned/reactive | Both proactive and reactive | Unplanned/reactive changes in the delivery of the intervention. |

| Planned Modifications | ||

| 3.1 Who determined the modification | Intervention developer, senior technical advisor, project coordinators, and project managers in CRS projects (Thrive I and II). | |

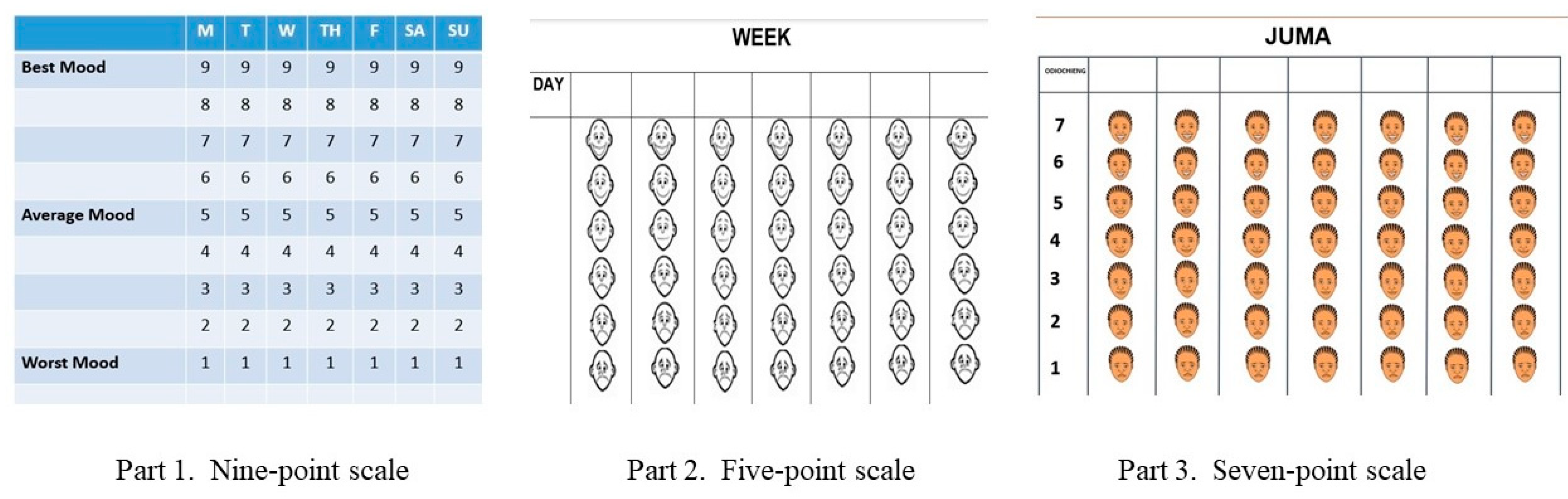

| 4.1 What is modified | (a) Content and training changed to adapt to the contexts of perinatal women in Thrive II. (b) The name of the intervention was changed from MBC to MBYC. (c) Format of the intervention changed from weekly to biweekly (d) Materials: Participants’ manuals changed to flip charts and spiral notebooks; the mood scale was changed to have faces instead of numbers, validated with mothers. (e) Translation of all materials to address local dialects/idioms (f) Separate facilitators for MBYC and ECD courses. (g) CRS recommends integrating the MBC into the existing home-visit structure. | |

| 5.1 At what level of delivery the modification is made | (a) Format of training increased from 2 to 5 days to adapt to the needs of local staff. (b) Sessions in the format were changed to adhere to the ECD intervention structure, timing (45 min), and staffing (biweekly). (c) MBYC and ECD took place concurrently. (d) Booster sessions for MBYC occurred at months 9 and 12. (e) Home visits were conducted for both ECD and MBYC interventions. | |

| 6.1 Type or nature content-level changes | Materials were modified to adapt to low literacy levels for participants and rural sub-Saharan contexts. | |

| Unplanned Modifications | ||

| 3.2 Who determined the modification | Intervention developer, CRS staff, project coordinator, project managers, and attendees at training. | The intervention developer, senior technical advisor, and program managers provided additional guidance on the delivery/process of intervention based on field visit observations. |

| 4.2 What is modified | (a) Materials: Spiral booklets to show core contents, take-home messages, and mood scales. (b) Add contextualized pictures and activities. (c) Timing of sessions (d) Adding a flipchart in addition to the materials for the facilitators (e) Onboarding of new staff to accommodate refresher trainings. | There was variability in how the intervention content was delivered/how much time was spent on each topic/teaching method in both countries. Therefore, contextual modifications (e.g., location and timing) were made in the delivery of the intervention and ways to improve the participant engagement process. |

| 5.2 At what level of delivery the modification is made | (a) Materials were modified for participants (spiral notebooks). (b) Flipcharts were added to accommodate delivery norms, which aligned with the materials used in the ECD intervention. | Rural Africa context (see planning phase). |

| 6.2 Type or nature content-level changes | (a) Names of characters changed to reflect more common names in Kenya and Tanzania (b) Timing of sessions drifted/changed based on the ECD intervention that is being delivered at each site | Few modifications were made to the content. |

| 7. The Relationship to fidelity | The core elements of the original MBC were retained: CBT, reality management, and attachment models. Fidelity was assessed through different forms for group sessions and home visits. These forms were reviewed by the intervention developer. | (a) Use of the previous version of MBC intervention materials limited fidelity at the beginning of the implementation phase. (b) Fidelity forms of group sessions were rated overall positively but did not always reflect the actual facilitator’s performance. (c) Due to limited budgetary issues, Case managers were responsible for too many groups, decreasing their ability to complete all content within sessions and rushing to deliver the next sessions with limited fidelity. (d) Additional clarity regarding how to conduct home visits and follow up of women who may need additional psychological services. |

| 8. The rationale for the modifications made | (a) Sociopolitical: limited resources devoted to mental health in sub-Saharan Africa (b) Organizational: CRS funding by Conrad N. Hilton to implement Thrive II activities; changes were made based on staffing and logistics set by CRS. (c) Provider: Nonmental health professionals were trained, due to limited providers who have more specialized skills in psychology or mental health, and limited financial incentives to recruit and retain specialized staff in rural areas. (d) Recipient: Adapting it to the needs of the local perinatal women live during the session. | In response to field observations:(a) Organizational: Reactive modifications resulted in CRS devoting additional resources to each community on time and according to their unique needs. (b) Provider: Case managers used new materials created. (c) Recipient: Changes made to increase fidelity, retention, engagement, and outcomes for perinatal women in Kenya and Tanzania. |

| Implementation Successes | Implementation Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ and Careggroup Volunteers’ Feedback (n = 5) | Increased awareness of mood and impact of stressors and depression | Timing of session (e.g., facilitators late to session) |

| Enjoyed relaxation and learning activities to manage daily stressors | Expectation of monetary incentives | |

| Valued group support | ||

| Enjoyed incentives (graduate certificates) | ||

| Case Managers’ Feedback (n = 6) | Found remote supervision helpful | Used old intervention materials |

| Role plays were helpful in reinforcing concepts and improving facilitation | Participants had varying levels of comprehension of materials | |

| Limited timing of session (e.g., not enough time to cover challenging concepts | ||

| Limited coordination of materials for MBC and ECD contents as they were presented separately | ||

| Large caseloads, leading to overscheduling and timing issues |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, H.-N.; McEwan, E.; Kapiyo, M.; Muthoni, F.; Opiyo, T.; Rabemananjara, K.M.; Senefeld, S.; Hembling, J. Preventing Perinatal Depression: Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Course in Kenya and Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196811

Le H-N, McEwan E, Kapiyo M, Muthoni F, Opiyo T, Rabemananjara KM, Senefeld S, Hembling J. Preventing Perinatal Depression: Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Course in Kenya and Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196811

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Huynh-Nhu, Elena McEwan, Maureen Kapiyo, Fidelis Muthoni, Tobias Opiyo, Kantoniony M. Rabemananjara, Shannon Senefeld, and John Hembling. 2023. "Preventing Perinatal Depression: Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Course in Kenya and Tanzania" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196811

APA StyleLe, H.-N., McEwan, E., Kapiyo, M., Muthoni, F., Opiyo, T., Rabemananjara, K. M., Senefeld, S., & Hembling, J. (2023). Preventing Perinatal Depression: Cultural Adaptation of the Mothers and Babies Course in Kenya and Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196811