Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with Psychotropic Medication and Mental Health Service Use among Children in Out-of-Home Care in the United States: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Service Use

1.3. Study Purpose

2. Method

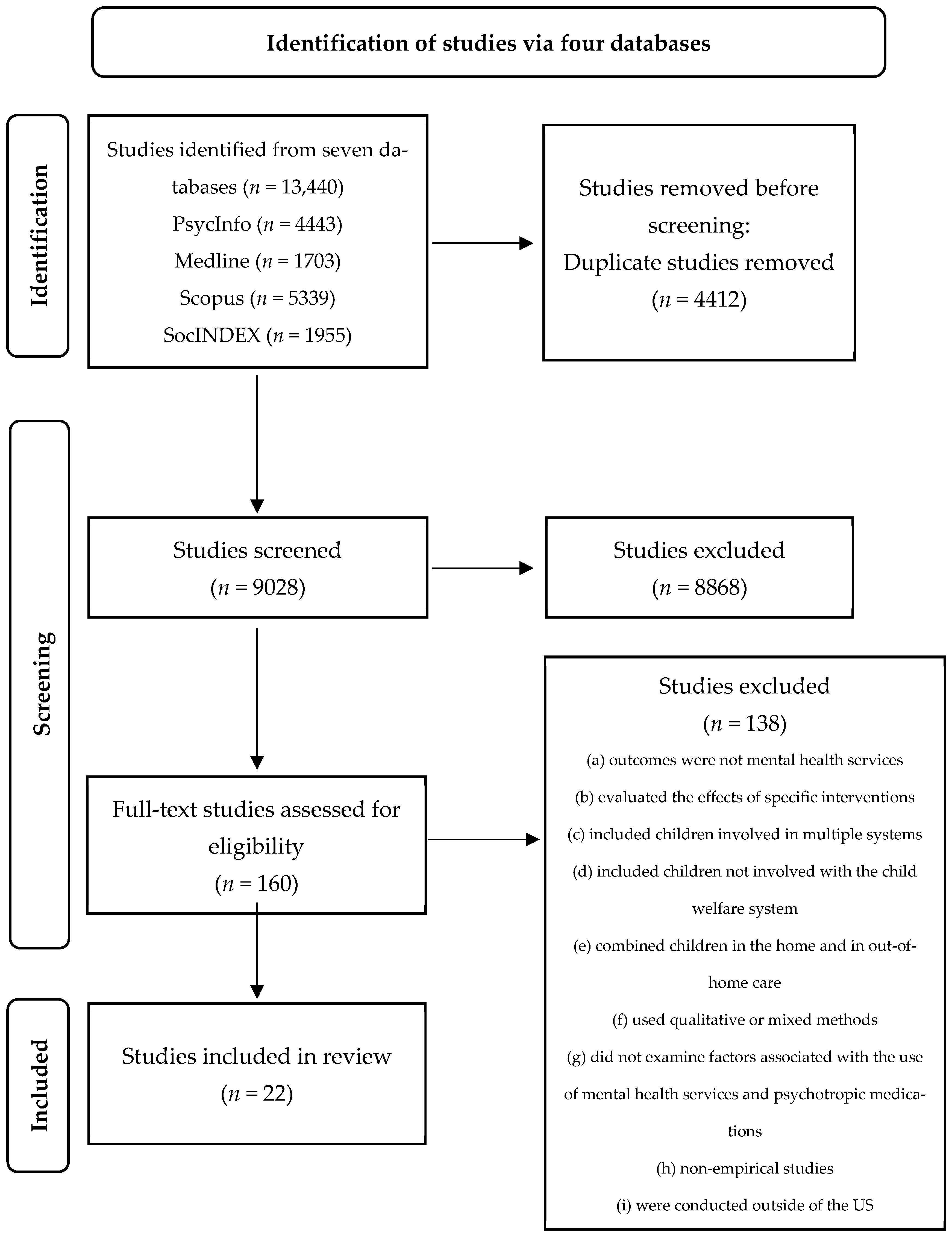

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Systematic Searches

2.4. Data Screening, Extraction, Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with the Use of Psychotropic Medications

3.3. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with the Use of Mental Health Services

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Directions for Future Research

4.5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Out-of-Home Care. Available online: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/outofhome/ (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in Foster Care and Adoption: FY 2012–2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/trends-foster-care-adoption (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Anctil, T.M.; McCubbin, L.D.; O’Brien, K.; Pecora, P. An evaluation of recovery factors for foster care alumni with physical or psychiatric impairments: Predictors of psychological outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2007, 29, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E.; Dworsky, A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2006, 11, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, P.J.; Jensen, P.S.; Romanelli, L.H.; Jackson, L.J.; Ortiz, A. Mental health services for children placed in foster care: An overview of current challenges. Child Welf. 2009, 88, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, E.P.; Oppenheim-Weller, S.; N’zi, A.M.; Taussig, H.N. Mental health interventions for children in foster care: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 70, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, P.J.; Williams, J.; Kessler, R.C.; Downs, A.C.; O’Brien, K.; Hiripi, E.; Morello, S. Assessing the Effects of Foster Care: Early Results from the Casey National Alumni Study; Casey Family Programs: Seattle, WA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, J.S.; Childs, G.E.; Kelleher, K.J. Mental health care utilization and expenditures by children in foster care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, L.K.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Landsverk, J.; Barth, R.; Slymen, D.J. Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: A national perspective. Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J.C.; Scott, L.D.; Zima, B.T.; Ollie, M.T.; Munson, M.R.; Spitznagel, E. Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004, 55, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, B.J.; Phillips, S.D.; Wagner, H.R.; Barth, R.P.; Kolko, D.J.; Campbell, Y.; Landsverk, J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Mental Health Services. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/mental-health-services (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Burns, B.J.; Costello, E.J.; Angold, A.; Tweed, D.; Stangl, D.; Farmer, E.M.; Erkanli, A. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Aff. 1995, 14, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Goldhaber-Fiebert, J.D.; Heneghan, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Rolls-Reutz, J.; Fisher, E.; Landsverk, J.; Stein, R.E. Mental health services use by children investigated by child welfare agencies. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Zima, B.T.; Andersen, R.M.; Leibowitz, A.A.; Schuster, M.A.; Landsverk, J. Psychotropic medication use in a national probability sample of children in the child welfare system. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutz, G.D. Foster Children: HHS Guidance Could Help States Improve Oversight of Psychotropic Prescriptions; U.S. Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Raghavan, R.; Brown, D.S.; Allaire, B.T.; Garfield, L.D.; Ross, R.E. Medicaid expenditures on psychotropic medications for maltreated children: A study of 36 states. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, L.K.; James, S.; Monn, A.; Kauten, M.C.; Zhang, J.; Aarons, G. Health-risk behaviors in young adolescents in the child welfare system. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, R.; Alexandrova, A. Toward a theory of child well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; McMillen, J.C. Use of multiple psychotropic medications among adolescents aging out of foster care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, K.; Yang, J.; Ferguson, K.; Thompson, S. Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 55, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, G.R.; Havlicek, J.R.; Courtney, M.E. Risk for arrest: The role of social bonds in protecting foster youth making the transition to adulthood. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2012, 82, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harris, M.S.; Jackson, L.J.; O’Brien, K.; Pecora, P.J. Disproportionality in education and employment outcomes of adult foster care alumni. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglehart, A.P.; Becerra, R.M. Hispanic and African American youth: Life after foster care emancipation. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 2002, 11, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Courtney, M.E.; Tajima, E. Extended foster care support during the transition to adulthood: Effect on the risk of arrest. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 42, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, S.; Rosenthal, J.A.; O’Brien, K.; Pecora, P. Health outcomes for adults in family foster care as children: An analysis by ethnicity. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, A.R. A mistreated epidemic: State and federal failure to adequately regulate psychotropic medications prescribed to children in foster care. Temple Law Rev. 2010, 83, 369–404. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.; Newman, J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Meml. Fund Q. Health Soc. 1973, 51, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, M.; Tempes, J.; Bitzer, E.M. Application of Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use: A scoping review with a focus on qualitative health services research. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Jedwab, M.; Soto-Ramirez, N.; Weist, M.D. The use of mental health services among children in kinship care: An application of Anderson’s behavioral model for health services use. J. Public Child Welf. 2023, 17, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsard, G.; Alessandrini, M.; Fond, G.; Loundou, A.; Auquier, P.; Tordjman, S.; Boyer, L. The prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the child welfare system: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2016, 95, e2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler, A.D.; Sarpong, K.O.; Van Horne, B.S.; Greeley, C.S.; Keefe, R.J. A systematic review of mental health disorders of children in foster care. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: https://www.covidence.org (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Bozzi, L.M.; Shah, P.; DosReis, S. Community adversity and utilization of psychotropic medications among children in foster care. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 49, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breland-Noble, A.M.; Elbogen, E.B.; Farmer, E.M.; Dubs, M.S.; Wagner, H.R.; Burns, B.J. Use of psychotropic medications by youths in therapeutic foster care and group homes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004, 55, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Breland-Noble, A.M.; Farmer, E.M.; Dubs, M.S.; Potter, E.; Burns, B.J. Mental health and other service use by youth in therapeutic foster care and group homes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2005, 14, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S.L.; Southerland, D.G.; Burns, B.J.; Wagner, H.R.; Farmer, E.M. Use of psychotropic medications among youth in treatment foster care. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DosReis, S.; Tai, M.H.; Goffman, D.; Lynch, S.E.; Reeves, G.; Shaw, T. Age-related trends in psychotropic medication use among very young children in foster care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 1452–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawley-King, K.; Snowden, L.R. Relationship between placement change during foster care and utilization of emergency mental health services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glesener, D.; Anderson, G.; Li, X.; Brown, J.; Amell, J.; Regal, R.; Ferguson, D. Psychotropic medication patterns for American Indian children in foster care. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Landsverk, J.; Slymen, D.J.; Leslie, L.K. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use—The role of foster care placement change. Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 6, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Barnhart, S.; Garcia, A.R.; Jung, N.; Wu, C. Changes in mental health service use over a decade: Evidence from two cohorts of youth involved in the child welfare system. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2021, 40, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, L.K.; Landsverk, J.; Ezzet-Lofstrom, R.; Tschann, J.M.; Slymen, D.J.; Garland, A.F. Children in foster care: Factors influencing outpatient mental health service use. Child Abus. Negl. 2000, 24, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J.C.; Raghavan, R. Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.; Okpych, N.J.; Courtney, M.E. Psychotropic medication use and perceptions of medication effects among transition-age foster youth. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2019, 36, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, C.L.; Culhane, S.E.; Garrido, E.F.; Taussig, H.N. Do youth in out-of-home care receive recommended mental health and educational services following screening evaluations? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pullmann, M.D.; Jacobson, J.; Parker, E.; Cevasco, M.; Uomoto, J.A.; Putnam, B.J.; Benshoof, T.; Kerns, S.E.U. Tracing the pathway from mental health screening to services for children and youth in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 89, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H. Need for and actual use of mental health service by adolescents in the child welfare system. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2005, 27, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanke, J.R.; Yampolskaya, S.; Strozier, A.; Armstrong, M.I. Mental health service utilization and time to care: A comparison of children in traditional foster care and children in kinship care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 68, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrana, M. Mental health services for children and youth in the child welfare system: A focus on caregivers as gatekeepers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrana, M. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use for older foster youth and foster care alumni. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2017, 34, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yampolskaya, S.; Sharrock, P.J.; Clark, C.; Hanson, A. Utilization of mental health services and mental health status among children placed in out-of-home care: A parallel process latent growth modeling approach. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zima, B.T.; Bussing, R.; Yang, X.; Belin, T.R. Help-seeking steps and service use for children in foster care. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 27, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashiell-Earp, C.; Zlotnik, S. Psychotropic medications and children in foster care. Policy Pract. 2011, 69, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Predictors Associated with Mental Health Service or Psychotropic Medication Use | |

|---|---|---|

| Bozzi et al., 2022 [37] | DV: Psychotropic use Predisposing: n/a Enabling: Community adversity – Need: n/a | |

| Breland-Noble et al., 2004 [38] | DV: Taking any medication Predisposing: White + Younger than 13 (ref: >13) − Enabling: Group home (ref: therapeutic foster care) + Need: Clinical range on externalizing CBCL subscale + Clinical ranges for both externalizing and internalizing subscales + | DV: Taking multiple medications Predisposing: Younger − Enabling: n/a Need: Clinical ranges on both externalizing and internalizing CBCL scores + |

| Breland-Noble et al., 2005 [39] | DV: Outpatient mental health Predisposing: Age − Enabling: Group home (ref: therapeutic foster care) + Need: CBCL total score + | DV: In-home counseling or crisis services Predisposing: African American (ref: White) + Enabling: n/a Need: CBCL total score + |

| Brenner et al., 2014 [40] | DV: Any psychotropic medication use Predisposing: Aged 6–12 (ref: 13–21) + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a | DV: ADHD medication Predisposing: Aged 6–12 (ref. 13–21) + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a |

| DosReis et al., 2014 [41] | DV: Antipsychotic Predisposing: Age + Enabling: n/a Need: Mood disorder (ref: no diagnosis) + Antidepressant (ref: no use) + ADHD medication (ref: no use) + DV: ADHD medication Predisposing: Age + Enabling: n/a Need: Disruptive behavior disorder + | DV: Mood stabilizer Predisposing: n/a Enabling: n/a Need: Disruptive behavior disorder − DV: Antidepressant Predisposing: Age + Enabling: n/a Need: Internalizing disorder + |

| Fawley-King and Snowden, 2012 [42] | DV: Subsequent crisis visit Predisposing: Hispanic (ref: White) − Aged 6–11 (ref: 12–18) − Enabling: n/a Need: Prior outpatient treatment (ref: none) + Day treatment (ref: none) + Inpatient stay (ref: none) + | DV: Subsequent psychiatric hospitalization Predisposing: Aged 6–11 (ref: 12–18) − Placement change prior to hospitalization (ref: none) + Enabling: n/a Need: Prior outpatient treatment (ref: none) + Day treatment (ref: none) + Inpatient stay (ref: none) + |

| Glesener et al., 2018 [43] | DV: Any psychotropic medication Predisposing: Aged 5–9 (ref: 15–17) − Time in foster care + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a DV: Antidepressant Predisposing: Aged 5–9 (ref: 15–17) − Time in foster care + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a DV: ADHD Predisposing: Aged 5–9 (ref: 15–17) − American Indian (ref: White) − Male + Time in foster care + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a | DV: Alpha-agonists Predisposing: Male + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a DV: Antipsychotic Predisposing: Aged 5–9 − Male + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a DV: Multiple medication classes Predisposing: Aged 5–9 − African American (ref: White) − American Indian (ref: White) − Male + Time in foster care + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a |

| James et al., 2004 [44] | DV: Number of mental health visits Predisposing: Female (ref: male) − Age at entry into out-of-home care + African American (ref: White) + Hispanic (ref: White) − Other (ref: White) − Caretaker absence − Enabling: Number of placement changes + Episodes in kinship care − Need: Behavior problems + | |

| Kim et al., 2021 [45] | DV: Receipt of MH service Predisposing: Age − Female (ref: male) − Latino (ref: White) + Juvenile justice involvement + Enabling: Placement instability + Placement type (ref: none) Foster care + Kinship care − Group home + Institution + Months in dependent care + Need: n/a | DV: Dosage of MH service Predisposing: Age − Female (ref: male) − Juvenile justice involvement − Enabling: Placement type (ref: none): Foster care + Kinship care + Group home + Institution + Months in dependent care + Need: Psychotic disorder + Mood disorder + Disruptive behavior disorder + Anxiety disorder + Adjustment disorder + Other disorder + Comorbidity + |

| Leslie et al., 2000 [46] | DV: Number of outpatient mental health visits Predisposing: Age + Latino (ref: White) − Asian or other (ref: White) − Male (ref: female) + Sexual abuse (ref: no) − Caregiver absence (ref: no) − Enabling: Kinship care only (ref: foster care only) − Kinship or foster care (ref: foster care only) − Need: Total CBCL ≥ 60 (ref: < 60) + | |

| Leslie et al., 2004 [9] | DV: Use of outpatient mental health service Predisposing: Aged 2–3 (ref: 11+) − Aged 6–10 (ref: 11+) − Physical neglect (ref: no) − Sexual abuse (ref: no) + Enabling: Group or residential care (ref: foster care) + Need: CBCL score ≥ 64 (ref: below 64) + | |

| McMillen and Raghavan, 2009 [47] | DV: Service retention Predisposing: Male (ref: female) − History of juvenile detention − Release from state custody prior to age 19 − Enabling: n/a Need: Posttraumatic stress disorder − DV: MH service discontinuation Predisposing: Youth of color + History of physical neglect − Each 6-month period of earlier discharge + Enabling: Congregate care (ref: other, with family, non-kinship foster family, and living more independently) − Need: n/a | DV: Psychotropic medication discontinuation Predisposing: Youth of color (ref: White) + History of penetrative sexual abuse (ref: no) − Enabling: Congregate care (ref: other, with family, non-kinship foster family, and living more independently) − Left care aged 17 to 17.5 (ref: did not leave before 19) + Left care aged 17.5 to 18 (ref: did not leave before 19) + Left care aged 18 to 18.5 (ref: did not leave before 19) + Left care aged 18.5 to 19: (ref: did not leave before 19) + Need: History of disruptive behavioral disorder + DV: Continued medication use across transition out of foster care Predisposing: Male (ref: female) − History of physical neglect – Enabling: n/a Need: n/a |

| McMillen et al., 2004 [10] | DV: Lifetime inpatient psychiatry Predisposing: Youth of color − Age at entrance to foster care system − Physical abuse (ref: no) + Sexual abuse (ref: no) + Enabling: n/a Need: Lifetime disorder (ref: no) + DV: Lifetime residential or group care Predisposing: Youth of color + Age at entrance to foster care system − Enabling: n/a Need: Lifetime disorder (ref: no) + DV: Lifetime outpatient therapy Predisposing: Youth of color − Age at entrance to foster care system − Physical abuse + Physical neglect − Sexual abuse + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a | DV: Current psychotropic medication Predisposing: Youth of color − Age at entrance to foster care system − Enabling: Congregate care (ref: non-kinship family foster home or living more independently) + Need: Disorder in past 12 months + DV: Current residential or group care Predisposing: Youth of color − Physical abuse − Enabling: n/a Need: Disorder in past 12 months + DV: Current outpatient therapy Predisposing: Youth of color − Enabling: n/a Need: Disorder in past 12 months + |

| Park et al., 2019 [48] | DV: Psychotropic medication use at age 17 Predisposing: n/a Enabling: Congregate care (ref: nonrelative foster home) + Independent living (ref: nonrelative foster home) + Need: Any mental health issue or substance use (ref. no diagnosis) + | DV: Psychotropic medication use at age 19 Predisposing: Used medication, agreed that good things outweigh bad things (ref: no meds) + Used medication, neutral that good things outweigh bad things (ref: no meds) + Used medication, disagreed that good things outweigh bad things (ref: no meds) + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a |

| Petrenko et al., 2011 [49] | DV: Receiving mental health services at Time 1 Predisposing: History of physical or sexual abuse (ref: other maltreatment type) + Enabling: Nonrelative foster care (ref: kinship) + Need: n/a | DV: Receiving mental health services at Time 2 Predisposing: n/a Enabling: n/a Need: Received recommendation for new services + |

| Pullmann et al., 2018 [50] | DV: Service receipt within 4 months among those screening above criteria Predisposing: Age at time of removal + African American in high-density county − Asian or Pacific Islander in high-density county − Physical abuse (ref: neglect) + Sexual abuse (ref: neglect) + Enabling: Relative caregiver (ref. all other) − Nonrelative caregiver (ref. all other) − Need: Bipolar + Anxiety + ADHD, conduct, impulsive disorder + Adjustment disorder + | DV: Service receipt within 4 months among those screening below criteria Predisposing: Age at time of removal + Physical abuse (ref: neglect) + Sexual abuse (ref: neglect) + Enabling: n/a Need: ADHD, conduct, impulsive disorder + Adjustment disorder + DV: Continued engagement in behavioral health or evidence-based services among those above criteria Predisposing: Physical abuse + Removal due to voluntary agreement (ref: court order) − Enabling: Caucasian in low-density county − African American in medium-density county − Native American in low-density county − First placement – Need: n/a |

| Shin et al., 2005 [51] | DV: Mental health service use Predisposing: Child abuse history (ref. no) + Time in care + Enabling: Nonrelative foster care (ref: kinship) + Need: Anxiety + Psychological well-being + | |

| Swanke et al., 2016 [52] | DV: Outpatient mental health services Predisposing: Hispanic (ref: non-Hispanic) + Physical abuse + Parental substance abuse + Age − Enabling: Placement in kinship care − Need: Physical health problems + Adjustment reaction disorder + Attention deficit disorder + Conduct disorder + Comorbidity − | |

| Villagrana, 2010 [53] | DV: Mental health utilization Predisposing: Aged 11–16 (ref: 5–10) + Sexual abuse (ref. neglect) + Enabling: Referral to mental health services (ref. not referred) + Need: n/a | |

| Villagrana et al., 2017 [54] | DV: Mental health service use during foster care Predisposing: Aged 18 (ref: 17) + Aged 19 (ref: 17) + Enabling: Other case closure reason (ref: court ordered) + Emancipation case closure (ref: court ordered) + Need: n/a | DV: Mental health service use after foster care Predisposing: Physical abuse (ref: neglect) + Sexual abuse (ref: neglect) + Latino (ref: White) − Enabling: Other case closure (ref: court ordered) + Emancipation case closure (ref: court ordered) + Need: n/a |

| Yampolskaya et al., 2017 [55] | DV: Mental health service use Predisposing: Male (ref: female) + Age + African American (ref: White) + Other race and ethnicity (ref: White) + Sexual abuse (ref: threatened harm) + Neglect (ref: threatened harm) + Maltreatment chronicity + Enabling: n/a Need: n/a | |

| Zima et al., 2000 [56] | DV: Mental health service referral for ADHD Predisposing: Foster parent education + Time in care – Enabling: n/a Need: n/a | DV: Mental health service referral for other diagnosis Predisposing: Foster parent education + Enabling: n/a Need: Level of comorbidity + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Winters, A.M.; Soto-Ramírez, N.; McCarthy, L.; Betz, G.; Liu, M. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with Psychotropic Medication and Mental Health Service Use among Children in Out-of-Home Care in the United States: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186769

Xu Y, Winters AM, Soto-Ramírez N, McCarthy L, Betz G, Liu M. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with Psychotropic Medication and Mental Health Service Use among Children in Out-of-Home Care in the United States: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(18):6769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186769

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yanfeng, Andrew M. Winters, Nelís Soto-Ramírez, Lauren McCarthy, Gail Betz, and Meirong Liu. 2023. "Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with Psychotropic Medication and Mental Health Service Use among Children in Out-of-Home Care in the United States: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 18: 6769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186769

APA StyleXu, Y., Winters, A. M., Soto-Ramírez, N., McCarthy, L., Betz, G., & Liu, M. (2023). Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors Associated with Psychotropic Medication and Mental Health Service Use among Children in Out-of-Home Care in the United States: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(18), 6769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186769