“Collapsing into Darkness”: An Exploratory Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Experience of Workplace Reintegration among Nurses with Operational Stress Injuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

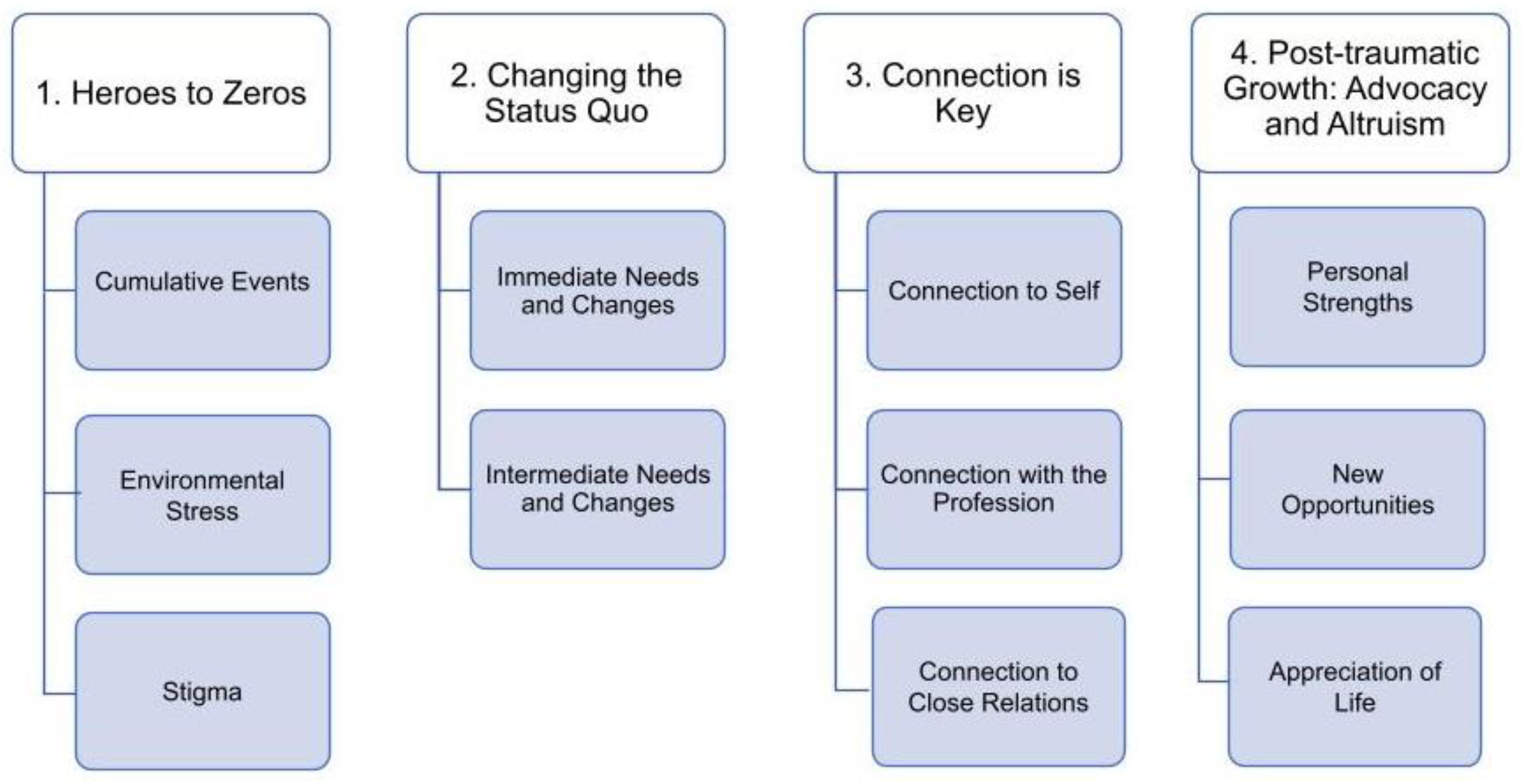

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Heroes to Zeros

“And that was when the dialogue was shifting from us being healthcare heroes to you know, that was just when the flavor really changed.”(P1)

Cumulative Events

“… what they were doing was torturing this man. And I really felt like I was part of it. And I had, I had to take like, some time off work I just called in sick for, I don’t know, maybe maybe just like a set, but it made it so that I had like, over a week off work. Just to kind of like deal with that, because I found it really upsetting to even be like near even like the thought of going to work made me like so anxious.”(P3)

“The paperwork says, well, what’s the one specific event or injury and in my mind, it’s a dozen events that are just right. And it’s not just one, it’s not just this…and it’s difficult to articulate on most forms because those forms are very regimented. For one problem, one injury, one solution done. That is not how complex psychological injuries work.”(P7)

“I think I felt really, like I did something and it was my fault. Like, what could I have done to make this not happen? Because clearly it happens in our workplace, but you just always think, like, it’ll never happen to me kind of thing. So I’m like, What did I do? Because we were always told, like, have exits, like, keep the curtains open. And I was like, I feel like I did that. Like he was on the other side of the structure. So it was a lot of replaying, and what did I do wrong? And I think I felt kind of embarrassed about it.”(P2)

Environmental Stress

“There’s a lot of, I think, stress within the healthcare scenario. And lots of things that I find challenging when you can’t do your work properly. You’re short staffed, I feel like I’m not caring about doing the job to the best, not because of myself, but because of the scenarios around.”(P4)

“But I also, there’s also that history there of being guilted to come into work, and that, you know, ignoring of concerns, our manager came to triage desk, and took off all the signs that were posted, saying like ‘this is a respectful workplace—violence and verbal abuse will not be tolerated.’ …she took down all those signs. And she said, this sends the wrong message to our patients. It’s not welcoming. And I said, ‘Well, what about when people are swearing at me, and I point to the sign saying, you can’t talk to me that way.’ And she’s like, ‘nothing bad ever happens at *site*.’”(P7)

“… in terms of trauma, and it’s like that’s what it felt like going in there. It’s like you didn’t have any idea how you were gonna make it through this shift, like, and how you were gonna be able to physically care for two people who were actively dying, you know, in trying to make sure they’re both okay. And plus, like, take care of yourself in any way like getting a break… and it’s, it is simple stuff like knowing that you can, you will be able to use the washroom when you need to use the washroom knowing like when you need water, you can get water.”(P3)

Stigma

“I think that really primed the pump for the PTSD. And just pretending and the denial. It’s not here. It’s not real. And kind of dissociating from what was happening. And then, the longer I stayed sick, the more angry I felt that it had happened, because I had done everything right. And I had done everything to prevent it and it still happened.”(P1)

“I’ve been in meetings where I’ve openly shared and been treated differently. I’ve been asked if I was well enough to do the work that I’m doing now by another nurse, and not in a way that was caring. Or it was in another way, that did not feel very nice.”(P5)

“It was just the thing to do. You just truck(ed) on, like, you know, like given 12 years ago, often people didn’t even want to admit if they had to take medications for depression or anything. And now that’s changing, and people are much more open about talking about it. But 12 years ago, there was still a fair bit of stigma regarding it.”(P4)

3.2.2. Changing the Status Quo

“Education or mental health resiliency, and all these things that we’re lacking, are more important than taking care of our patients. If we’re not healthy, our patients aren’t going to be well either.”(P7)

Immediate Needs and Changes

“I think there is no clear process for acknowledging when somebody has had a psychological injury. Yeah, so not the same way as if I’ve had a back injury. There’s a very clear return-to-work process (for physical injury).”(P1)

“I don’t think anybody ever talked about anything. Except my co-workers were very upset because, they were like, this could happen to anybody in our department. And I think they wanted to hear something from managers, they wanted to have some sort of debriefing or some sort of ability to talk about kind of what happened.”(P2)

Intermediate Needs and Changes

“I wouldn’t kind of just work myself so hard. And that’s what I felt that I needed to do last time. But I’m sitting here as you ask these questions, I’m like ‘Why? Why did I have no idea but there wasn’t anyone directing the kind of time off or the comeback other than me so I was the one making those decisions?”(P6)

“But I think had I been offered, like, some kind of a slower, like, reintroduction to work, which I know would have been really hard to support, especially like last summer. But that would have been helpful, I think, because it was… it was really tough to go back to, like, full time caring for it.”(P3)

“… * the province* not having presumptive PTSD legislation I had to go through an extensive process. I had to go through a comprehensive psychological assessment. But of course, it was five months after the fact.”(P7)

3.2.3. Connection Is Key

Connection to Self

“When you’re in the darkest moments of this…there’s an identity crisis, there’s like, “am I ever going to nurse again?” and “what the hell is happening to me”, like you just, it feels like, just a cloud, you’ve lost a piece of yourself, you don’t know who you are anymore.”(P5)

“My guilt for being home was crippling. And I don’t say that lightly. But it was because here I am. I’m like ‘here, I’m an emergency nurse. This is my passion, my profession. This is what I’ve been trained for. And here I am at home crying when my coworkers are suffering’.”(P7)

“And I guess taking that time off. And like, losing touch with that, I guess, like not not being able to consider that kind of like my primary, a primary part of my identity or having to think like, will I be able to stay in ICU? Like, do I need to take a different type of job and like, this is what I love. I guess I kind of realized that maybe I need to, like take a step back and kind of take, you know, I can care about what I do. But it’s also… it is just a job. And I need to, like, prioritize myself over any of this.”(P3)

Connection with the Profession

“And no one even, from management or anything, even like checked on me, which I really felt, like, annoyed and upset about at the time. But now I’m kind of like, ‘I don’t know’. If they…don’t know what they’re kind of, like, allowed to do in terms of like, not overstepping boundaries, but it felt kind of like, insensitive, like, no one really said, like, “Oh, how are you feeling? Are you okay?” Or whatever. It’s just like…I didn’t even leave…my work friends, the people I work with were really good…they were really supportive.”(P6)

“My manager, who had just come in, I had never met her before you emailed me and said, I know what happened to you. I’m really sorry, I’m here. These are some mental health resources. I’m a big proponent of it. She was great. Rather than the previous cadre who had just kind of slid the brochure across the table, you know.”(P1)

“And she (colleague) checks on me like she, we kind of check on each other. She’s someone that like, seems to cope really well with all this stuff. But she’s someone I can definitely, like, count on. And then I know that like, if I were to ever just tell my friends like I’m having a really bad day or whatever…they would be there for me.”(P3)

Connection to Family and Friends

“I told my parents, my parents don’t live here. And from *province* my dad, and my mom. And my brother is my only family who lives here. And he said, “You know, I don’t know if this job is the best for you.” I’ve always had lots of family and friends around me, so I’m blessed in that way. And, they also noticed that I was isolating. So my husband, you know, we were just keeping it together…I said to him, finally, I’m like, you got to go and talk to someone because, like, I know, this was hard on you.”(P5)

“[M]y partner unfortunately wasn’t…I don’t think he really even had the capacity to be and then like, also, you know, living with someone that’s depressed and anxious and stuff, and not knowing how to deal with that is probably not easy either. So yeah, that, that I ended up ending that relationship.”(P3)

“I think having somebody there to be able to talk to you, that’s a safe person. Yeah. And I would say, like, really reach out to your support system, because I don’t know what I would do without them. Yeah. I genuinely, like, that sounds very scary, but I don’t think I would still be here without them. I think I would have, like, I think I really would have collapsed in the darkness.”(P2)

3.2.4. Post-Traumatic Growth: Advocacy and Altruism

Personal Strengths

“Some of the differences is that I will realize when I’m getting low, that I will necessarily take a mental health day versus…not. Not having a clue that there’s days when I just know, mentally I need to do that. And I would say there was definitely days when I was redeployed to ICU that I did take more mental health days last fall… I just, I knew I’m like, that’s it. I can’t come back to this scenario tonight. I have realized that sometimes there’s things that I’m just like, need some time out?”(P4)

“So working on that with people and just kind of being an advocate for workplace safety. And helping some of my co-workers and another co-worker got punched in the face by a kid. And just like helping with like, K, you need to do this*workers compensation organization*, you need to go get checked out by a doctor and just kind of being somebody there for support and the department.”(P2)

“I have a lot more empathy. For everybody with every mental health concern, I always did. But man…”(P1)

New Opportunities

“I don’t have to continue in emergency if I don’t want to. I don’t need to be a trauma nurse. I really wanted to be a trauma nurse… But now I’m kind of like, I don’t want that stress in my life. And I will be okay. Without that I don’t need that; I will kind of do the work that makes me happy.”(P2)

“I am now driven and very passionate for supporting mental health for nurses. And I have a lot of experience and knowledge that I want to share with other nurses because there is a substantial gap of knowledge within our profession, and that needs to be addressed, and it’s not in a negative way.”(P7)

Appreciation of Life

“… [I]t almost kind of feels like I don’t owe *healthcare organization* my life anymore. Yeah, I feel like I’ve kind of gotten into being a nurse is not my whole life. There are other things to life that matter. So now I will take my personal days if I need to.”(P2)

“I can happily say that I am very grateful for the experiences that I’ve had, because I have this new knowledge I would have never had. And that’s, you know, someone who’s talking that’s done a lot, a lot of work and healing. And, you know, so there’s a lot of gratitude there.”(P5)

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.1.1. Addressing OSI

4.1.2. Workplace Reintegration: Policy, Initiatives, and Implementation

4.1.3. Future Research

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI). Creating a Safe Space: Strategies to Address the Psychological Safety of Healthcare Workers. 2020. Available online: www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Federal Framework on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. Available online: https://canadacommons.ca/artifacts/1421529/federal-framework-on-posttraumatic-stress-disorder/2035578/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Stelnicki, A.; Carleton, R. Mental Disorder Symptoms Among Nurses in Canada. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: A scoping review. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Pignatiello, G.; Kim, M.; Jun, J.; O’Mathúna, D.; Duah, H.; Taibl, J.; Tucker, S. Moral Injury, Nurse Well-being, and Resilience Among Nurses Practicing During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JONA: J. Nurs. Adm. 2022, 52, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT). Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (Version 2.1). Regina, SK. 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10294/9055 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Smith-MacDonald, L.; Lusk, J.; Lee-Bagsley, D.; Bright, K.; Laidlaw, A.; Voth, M.; Spencer, S.; Cruickshan, E.; Pike, A.; Jones, C.; et al. Companions in the Abyss: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study of an Online Therapy Group for Healthcare Providers Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry Spec. Issue Emerg. Issues Treat. Moral Inj. Moral Distress 2021, 12, 801680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias-Anderson, D. The Process of Work Re-Entry for Nurses after Substance Use Disorders Treatment: A Grounded Theory Study. 2016. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA, 1929. Available online: https://commons.und.edu/theses/1929 (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Jones, C.; O’Greysik, E.; Juby, B.; Spencer, S.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Vincent, M.; Bremault-Phillips, S. How do we keep our heads above water?: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study Exploring Implementation of a Workplace Reintegration Program for Nurses affected by Operational Stress Injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Covell, C.L.; Sands, S.R.; Ingraham, K.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Price, S.L.; Reichert, C.; Bourgeault, I.L. Mapping the Peer-Reviewed Literature on Accommodating Nurses’ Return to Work After Leaves of Absence for Mental Health Issues: A Scoping Review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Koln. Z Soz. Sozpsychol. 2017, 69 (Suppl. S2), 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Guide to Promoting Health Care Workforce Well-Being during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic; Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI): Boston, MA, USA, 2020. Available online: www.ihi.org (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Rivers, F.M.; Dukes, S.; Hatzfeld, J.; Yoder, L.H.; Gordon, S.; Simmons, A. Understanding Post-Deployment Reintegration Concerns Among En Route Care Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.; Polaschek, D.L.L. Evaluating Return-to-Work Programmes after Critical Incidents: A Review of the Evidence. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2022, 37, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Bright, K.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Pike, A.D.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Peers Supporting Reintegration After Occupational Stress Injuries: A Qualitative Analysis of a Workplace Reintegration Facilitator Training Program Developed by Municipal Police for Public Safety Personnel. Police J. Theory Pract. Princ. 2021, 95, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Spencer, S.; Juby, B.; O’Greysik, E.; Vincent, M.L.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Stakeholder Experiences of a Public Safety Personnel Workplace Reintegration Program. J. Community Saf. Wellbeing 2023, 8 (Suppl. S1), S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Sippel, L.; Krystal, J.; Charney, D.; Mayes, L.; Pietrzak, R. Why are some individuals more resilient than others: The role of social support. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angres DHBettinardi-Angres, K.; Cross, w. Nurses with Chemical Dependency: Promoting Successful Treatment and Reentry. J. Nurs. Regul. 2010, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, M. Implementation of Peer Support Groups for Nurses in Delaware’s Professional Health Monitoring Program; Wilmington University, Wilmington Manor, Delaware, United States ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018; p. 10812395. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, M.E.; Scannell-Desch, E. After the Parade: Military Nurses’ Reintegration Experiences from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. 2015, 53, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, S.; Schlundt, D.; Smith, P. Community-Engaged Research Perspectives: Then and Now. Acad. Pediatr. 2013, 13, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, L.; Moore, E.; Rein, A. Evaluating Patient and Stakeholder Engagement in Research: Moving From Theory to Practice. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2015, 4, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Pike, A.; Bright, K.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Workplace Reintegration Facilitator Training Program for Mental Health Literacy and Workplace Attitudes of Public Safety Personnel: Pre-Post Pilot Cohort Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e34394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Union. Canada’s Nurses and Presumptive Legislation for COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://nursesunions.ca/canadas-nurses-and-presumptive-legislation-for-covid-19/#:~:tex (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health Workforce in Canada: In Focus (Including Nurses and Physician) [Report]. 2021. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-workforce-in-canada-in-focus-including-nurses-and-physicians (accessed on 13 May 2023).

| Participant Demographics | Frequency (n/%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 7/100 |

| Male | 0/0 | |

| Intersex | 0/0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 0/0 | |

| Gender | Woman or feminine | 7/100 |

| Man or masculine | 0/0 | |

| Transgender man, male, or masculine | 0/0 | |

| Transgender woman, female, or feminine | 0/0 | |

| Gender nonconforming, genderqueer, or gender questioning | 0/0 | |

| Two-spirit | 0/0 | |

| Prefer not to specify | 0/0 | |

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 1/14 |

| 25–34 | 1/14 | |

| 35–44 | 1/14 | |

| 45–54 | 2/29 | |

| 55–64 | 0/0 | |

| 65+ | 0/0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 2/29 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 6/86 |

| South Asian (e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, etc.) | 1/14 | |

| Chinese | 0/0 | |

| Black | 0/0 | |

| Filipino | 0/0 | |

| Latin American | 0/0 | |

| Arab | 0/0 | |

| Southeast Asian (e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai, etc.) | 1/14 | |

| West Asian (e.g., Iranian, Afghan, etc.) | 0/0 | |

| Korean | 0/0 | |

| Japanese | 0/0 | |

| Indigenous, Metis, Inuit | 0/0 | |

| Other/Unknown | 0/0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1/14 | |

| Highest Level of Education | High School Diploma | 0/0 |

| Vocational or technical college | 0/0 | |

| College Diploma | 0/0 | |

| Some undergraduate | 0/0 | |

| Undergraduate degree | 5/71 | |

| Graduate degree | 2/29 | |

| Professional Role | Registered Nurse | 7/100 |

| Registered Psychiatric Nurse | 0/0 | |

| Licensed Practical Nurse | 0/0 | |

| Nurse Practitioner | 0/0 | |

| Years in Profession | 0–4 | 2/29 |

| 5–9 | 1/14 | |

| 10–14 | 2/29 | |

| 15–19 | 1/14 | |

| 20–24 | 1/14 | |

| 25–29 | 0/0 | |

| 30+ | 0/0 | |

| Years with Provincial Health Organization | 0–4 | 2/29 |

| 5–9 | 1/14 | |

| 10–14 | 3/43 | |

| 15–19 | 0/0 | |

| 20–24 | 1/14 | |

| 25–29 | 0/0 | |

| 30+ | 0/0 | |

| Psychological Exposure to Trauma | Yes | 7/100 |

| No | 0/0 | |

| No Answer/Prefer not to say | 0/0 | |

| Psychological Distress as a Result of Trauma Exposure in the Workplace | Yes | 7/100 |

| No | 0/0 | |

| No Answer/Prefer not to say | 0/0 | |

| Sought Mental Health Care as a Result of Trauma Exposure in the Workplace | Yes | 7/100 |

| No | 0/0 | |

| No Answer/Prefer not to say | 0/0 | |

| Time off Work Due to Exposure to Psychological Trauma in the Workplace | Yes | 6/86 |

| No | 0/0 | |

| No Answer/Prefer not to say | 1/14 | |

| Participation in a Workplace Reintegration or Return-to-Work Process | Yes | 2/29 |

| No | 5/86 | |

| No Answer/Prefer not to say | 0/0 | |

| Return to Work Status | Full-time, previous role | 4/57 |

| Part-time, restricted duties, and/or different role | 2/29 | |

| Have not returned to workplace | 1/14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, C.; Juby, B.; Spencer, S.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; O’Greysik, E.; Vincent, M.; Mooney, C.; Bright, K.S.; Sevigny, P.R.; Burback, L.; et al. “Collapsing into Darkness”: An Exploratory Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Experience of Workplace Reintegration among Nurses with Operational Stress Injuries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176664

Jones C, Juby B, Spencer S, Smith-MacDonald L, O’Greysik E, Vincent M, Mooney C, Bright KS, Sevigny PR, Burback L, et al. “Collapsing into Darkness”: An Exploratory Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Experience of Workplace Reintegration among Nurses with Operational Stress Injuries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(17):6664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176664

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Chelsea, Brenda Juby, Shaylee Spencer, Lorraine Smith-MacDonald, Elly O’Greysik, Michelle Vincent, Colleen Mooney, Katherine S. Bright, Phillip R. Sevigny, Lisa Burback, and et al. 2023. "“Collapsing into Darkness”: An Exploratory Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Experience of Workplace Reintegration among Nurses with Operational Stress Injuries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 17: 6664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176664

APA StyleJones, C., Juby, B., Spencer, S., Smith-MacDonald, L., O’Greysik, E., Vincent, M., Mooney, C., Bright, K. S., Sevigny, P. R., Burback, L., Greenshaw, A., Carleton, R. N., Savage, R., Hayward, J., Zhang, Y., Cao, B., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2023). “Collapsing into Darkness”: An Exploratory Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Experience of Workplace Reintegration among Nurses with Operational Stress Injuries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(17), 6664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176664