Post-Natal Short-Term Home Visiting Programs: An Overview and a Volunteers-Based Program Pilot

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Early Home Visiting Interventions

2.2. Universal Home Visiting Programs

2.3. Short-Term, Universal, Post-Natal Programs

2.4. Volunteer-Based, Home Visiting Interventions

3. Literature Summary as Background to a New Program

3.1. New Pilot for Infant Risk Prevention Home Visiting Program Based on Volunteers

3.2. Main Objectives of the Program

3.3. Intervention Description

3.4. Main Principles of the Program

3.5. Content of the Visits

3.6. The Program Development Process

3.7. Program Implementation Process and Challenges

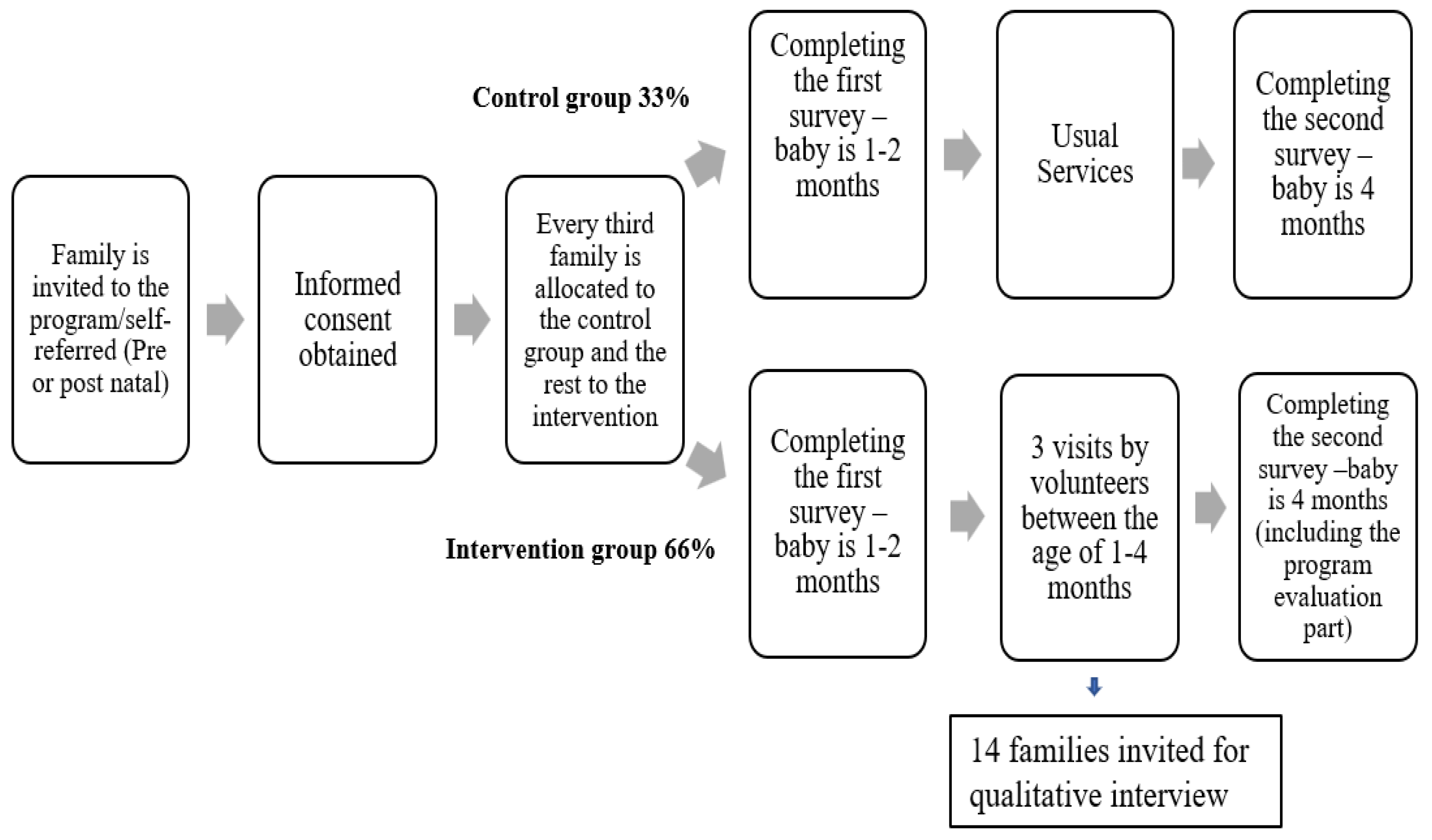

3.8. Planned Study and Evaluation

4. Discussion: Raising Issues in Program Implementation

4.1. Cultural Adaptation

4.2. Dealing with Unexpected Events

4.3. Reciprocal Relationship with the Community

4.4. Program Resources and Affiliation

4.5. Adherence to Study Protocols

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Home Visiting Program

| Part | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Introducing the program and its purpose, creating a relaxed atmosphere and pleasant communication with the parents, while addressing them personally, conveying the message that they are not alone. |

| 2. Recognizing the baby’s condition | Raising awareness of the importance of paying attention to the baby’s condition and recognizing and identifying his/her gestures. |

| 3. How to deal when the baby cries a lot | Interest in the challenging situations and raising awareness of the role of crying in babies, coping with crying and situations of loss of control, the shaking baby syndrome (abusive head trauma). |

| 4. Needs following birth | Filling out a needs-based questionnaire, perception of parenting, personal wellbeing. |

| 5. Introduction to services and areas they need | Examination of familiarity with the main relevant services and brief introduction to unfamiliar services. Checklist of contents they were interested in. Checking needs, is there a need for a connection to the services? |

| 6. Summary and wrap-up | Acknowledgment, repeating the message about how important they are to the baby and how difficult parenting can be. Coordinate a second visit. |

| Part | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Explanation of the focus of the visit—child safety, presentation of the rationale of the service (injury data) | To create connection, using stories and personal experience and address the possibility of discomfort that may arise following entering the personal space. |

| 2. Accident prevention explanation: basic principles for injury prevention | Making a connection between safe environment, safe behavior, and flexibility to the family’s needs. |

| 3. Safeguarding the children using the “Hat’ama” model | Parents are required to constantly monitor their children and identify where a problem may develop and immediately think of a solution. This is not simple, but possible with the help of the “Hat’ama” model, which enables the examination of alternatives to an existing risk situation and the identification of solutions using scenarios written in a transcript. |

| 4. Tour of the house and filling out the checklist | Identification of the situation at home (it is possible to mark more than one answer in the checklist), use of safety accessories, practice: identification of risk situations, identification risks, identification of safe situations, identification of solutions using the “Hat’ama” model. |

| 5. End of visitation | Connection to the model, signing a safety commitment, an explanation of how to fill in the diary, a request to fill in the diary to learn from their experience and passing on the information to other families and parents. |

| Part | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Importance of interaction with the baby | The importance of interaction with the baby, behaviors that are important to incorporate into activities with the baby (including demonstrations with the baby), the importance of speaking and reading books from an early age, appropriate interaction, and stimulation during the day. |

| 2. Mental state of the parent | Raising awareness of the impact of our mental state on the baby and on our ability to function and care, awareness of postpartum depression, the impact of past experiences and uncontrollable factors, and the importance of seeking help if necessary. |

| 3. Postpartum relationship | The process of adapting the relationship to life after giving birth, particularly the need to find time, and looking at gaps in the couple’s experience of change. Attention to continued family planning. |

| 4. End of visit | Saying thank you. Extending an invitation to keep in touch with the Early Childhood Center and volunteer for the program. |

References

- Fang, X.; Brown, D.S.; Florence, C.S.; Mercy, J.A. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Amos, J. The serious health consequences of abuse and neglect in early life. BMJ 2023, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikton, C.; Butchart, A. Child maltreatment prevention: A systematic review of reviews. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsell, D.; Avellar, S.; Sama Martin, E.; Del Grosso, P. Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness Review: Executive Summary; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Administration for Children and Families. The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home: Visiting Program Partnering with Parents to Help Children Succeed; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/programs/home-visiting/maternal-infant-early-childhood-home-visiting-miechv-program (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Gross-Manos, D.; Melckman, E.; Almog-Zaken, A. Child protection in Israel: Main legislation, services and delivery model. In International Handbook of Child Protection Systems; Berrick, J.D., Gilbert, N., Skivenes, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, K.A.; Goodman, W.B.; Murphy, R.A.; O’Donnell, K.; Sato, J.; Guptill, S. Implementation and randomized controlled trial evaluation of universal postnatal nurse home visiting. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S136–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, K.A.; Goodman, W.B.; Bai, Y.; O’Donnell, K.; Murphy, R.A. Effect of a community agency-administered nurse home visitation program on program use and maternal and infant health outcomes: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1914522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, R.; Kemp, L.; Barnes, J.; Elcombe, E.; Knight, J.; Baird, K.; Webster, V.; Byrne, F. Community volunteer support for families with young children: Protocol for the volunteer family connect randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e10000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffin, M.; Hecht, D.; Bard, D.; Silovsky, J.F.; Beasley, W.H. A statewide trial of the SafeCare home-based services model with parents in Child Protective Services. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Chan, K.L. Effects of parenting programs on child maltreatment prevention: A meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 17, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In Examining Lives in Context; Moen, P., Elder, G.H., Jr., Luscher, K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 619–647. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; The Tavistock Institute of Humans Relations: London, UK, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Olds, D.L. The nurse–family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Ment. Health J. 2006, 27, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, R.D. Universal Home Visiting: A Recommendation from the U.S. Advisory Board on child abuse and neglect. Future Child. 1993, 3, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Howard, K.S.; Brooks-Gunn, J. The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. Future Child. 2009, 19, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nievar, M.A.; Van Egeren, L.A.; Pollard, S. A meta-analysis of home visiting programs: Moderators of improvements in maternal behavior. Infant Ment. Health J. 2010, 31, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.; Harris, E.; McMahon, C.; Matthey, S.; Vimpani, G.; Anderson, T.; Schmied, V.; Aslam, H.; Zapart, S. Child and family outcomes of a long-term nurse home visitation programme: A randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 2011, 96, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.; Konrad, S.; Watson, E.; Nickel, D.; Muhajarine, N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olds, D.L.; Henderson, C.R.; Chamberlin, R.; Tatelbaum, R.T. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics 1986, 78, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, K.A.; Goodman, W.B.; Murphy, R.A.; O’Donnell, K.; Sato, J. Randomized controlled trial of universal postnatal nurse home visiting: Impact on emergency care. Pediatrics 2013, 132, S140–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olds, D.L.; Henderson, C.R.; Kitzman, H. Does prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation have enduring effects on qualities of parental caregiving and child health at 25 to 50 months of life? Pediatrics 1994, 98, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, L.; Johnson, M. An Evaluation of a Volunteer-Support Program for Families at Risk. Public Health Nurs. 2004, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellar, S.A.; Supplee, L.H. Effectiveness of home visiting in improving child health and reducing child maltreatment. Pediatrics 2013, 132 (Suppl. S2), S90–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler, K.; Silva, C.; Manning, S.E.; Harvey, E.M.; Posner, E.; Walmer, B.; Downs, K.; Kotelchuck, M. Lessons learned: Implementation of pilot universal postpartum nurse home visiting program, Massachusetts 2013–2016. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, K.; Goodman, B. Durham Connects Impact Evaluation Final Report; Pew Center on the States: Durham, NC, USA, 2012; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Baziyants, G.A.; Dodge, K.A.; Bai, Y.; Goodman, W.B.; O’Donnell, K.; Murphy, R.A. The effects of a universal short-term home visiting program: Two-year impact on parenting behavior and parent mental health. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 140, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, W.B.; Dodge, K.A.; Bai, Y.; Murphy, R.A.; O’Donnell, K. Effect of a universal postpartum nurse home visiting program on child maltreatment and emergency medical care at 5 years of age: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2116024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, A.; Zimmermann, K.; Dominik, B. Universal early home visiting: A strategy for reaching all postpartum women. Matern Child Health J. 2019, 23, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family Connects International. Fci Mission Alignment and Fit. 2023. Available online: https://familyconnects.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2023-FCI-Primer.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Dennis, C.L.; Hodnett, E.; Kenton, L.; Weston, J.; Zupancic, J.; Stewart, D.E.; Kiss, A. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: Multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009, 338, a3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibanda, D.; Weiss, H.A.; Verhey, R.; Simms, V.; Munjoma, R.; Rusakaniko, S.; Chingono, A.; Munetsi, E.; Bere, T.; Manda, E.; et al. Effect of a primary care-based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 2618–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibanda, D. Programmes that bring mental health services to primary care populations in the international setting. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, K.; Barnes, J.; Nichols, M.; Dixon, S. Volunteer support for mothers with new babies: Perceptions of need and support received. Child. Soc. 2009, 24, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.; Gillies, V. Support in parenting: Values and consensus concerning who to turn to. J. Soc. Policy 2004, 33, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adha, M.M. Advantages of volunteerism values for Indonesian community and neighborhoods. Int. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2019, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pesut, B.; Duggleby, W.; Warner, G.; Fassbender, K.; Antifeau, E.; Hooper, B.; Greig, M.; Sullivan, K. Volunteer navigation partnerships: Piloting a compassionate community approach to early palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akister, J.; Johnson, K.; McKeigue, B.; Ambler, S. Parenting with home-start: Users’ views. Practice 2003, 15, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, A.V.; Short, S.D.; Barclay, L. “She has made me feel human again”: An evaluation of a volunteer home-based visiting project for mothers. Health Soc. Care Community 2000, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaitz, M.; Chriki, M.; Tessler, N.; Levy, J. Predictors of self-reported gains in a relationship-based home-visiting project for mothers after childbirth. Infant Ment. Health J. 2018, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J. The impact on child developmental status at 12 months of volunteer home-visiting support. Child Dev. Res. 2012, 2012, 728104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; MacPherson, K.; Senior, R. Factors influencing the acceptance of volunteer home-visiting support offered to families with new babies. Fam. Soc. Work 2006, 11, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; MacPherson, K.; Senior, R. The impact on parenting and the home environment of early support to mothers with new babies. J. Child. Serv. 2006, 1, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Senior, R.; MacPherson, K. The utility of volunteer home-visiting support to prevent maternal depression in the first year of life. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asscher, J.J.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Deković, M. Effectiveness of the home-start parenting support program: Behavioral outcomes for parents and children. Infant Ment. Health J. 2008, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, T.H.; Annisa, Y.N. Home-Start Parenting Program: Supporting Maternal Emotional Functioning in Raising Young Children. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Early Childhood Education (ICECE 2016), Bandung, Indonesia, 11–12 November 2016; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Asscher, J.J.; Deković, M.; Prinzie, P.; Hermanns, J.M.A. Assessing change in families following the home-start parenting program: Clinical significance and predictors of change. Fam. Relat. 2008, 57, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns JM, A.; Asscher, J.J.; Zijlstra BJ, H.; Hoffenaar, P.J.; Dekovič, M. Long-term changes in parenting and child behavior after the Home-Start family support program. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aar, J.V.; Asscher, J.J.; Zijlstra, B.J.H.; Deković, M.; Hoffenaar, P.J. Changes in parenting and child behavior after the home-start family support program: A 10-year follow-up. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 53, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.; Molloy, B.; Scallan, E.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Rooney, B.; Keegan, T.; Byrne, P. Community Mothers Programme—Seven year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of non-professional intervention in parenting. J. Public Health Med. 2000, 22, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, J.; Madhala, S. Developments in Israeli Social Welfare Policy. In The State of the Nation Report 2017; Taub Center: Jerusalem, Israel, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury, J.C.; Dalton, J.E.; Haas, B.M.; Korbin, J.E. “A rising tide floats all boats”: The role of neighborhood collective efficacy in responding to child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 124, 105461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrick, S.; Smith, G.; Nicholson, J. Parenting and Families in Australia; Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Wellbeing Group. Personal Wellbeing Index, 5th ed.; Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 12, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibaud-Wallston, J.; Wandersman, L.P. Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC); APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Esba, H.; Carcara-Ibrahim ALevi, S.; Andi-Findeling, L. Parents of 15-Year-Old and Younger Perspectives on Home Safety; Masaar Institute and Beterem-Safe Kids Israel: Petah Tikva, Israel, 2009; Report #1059. [Google Scholar]

- Cwikel, J.; Segal-Engelchin, D.; Niego, L. Addressing the needs of new mothers in a multi-cultural setting: An evaluation of home visiting support for new mothers—Mom to Mom (Negev). Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, N.; Habibi, R.; Smith, R.; Manthorpe, J. Barriers to access and minority ethnic carers’ satisfaction with social care services in the community: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 23, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gross Manos, D.; Bader, N.G.; Cohen, A. Post-Natal Short-Term Home Visiting Programs: An Overview and a Volunteers-Based Program Pilot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176650

Gross Manos D, Bader NG, Cohen A. Post-Natal Short-Term Home Visiting Programs: An Overview and a Volunteers-Based Program Pilot. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(17):6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176650

Chicago/Turabian StyleGross Manos, Daphna, Noha Gaber Bader, and Ayala Cohen. 2023. "Post-Natal Short-Term Home Visiting Programs: An Overview and a Volunteers-Based Program Pilot" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 17: 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176650

APA StyleGross Manos, D., Bader, N. G., & Cohen, A. (2023). Post-Natal Short-Term Home Visiting Programs: An Overview and a Volunteers-Based Program Pilot. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(17), 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176650