Climate Change and Health: Challenges to the Local Government Environmental Health Workforce in South Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results: Participant Demographics and Workplace Profiles

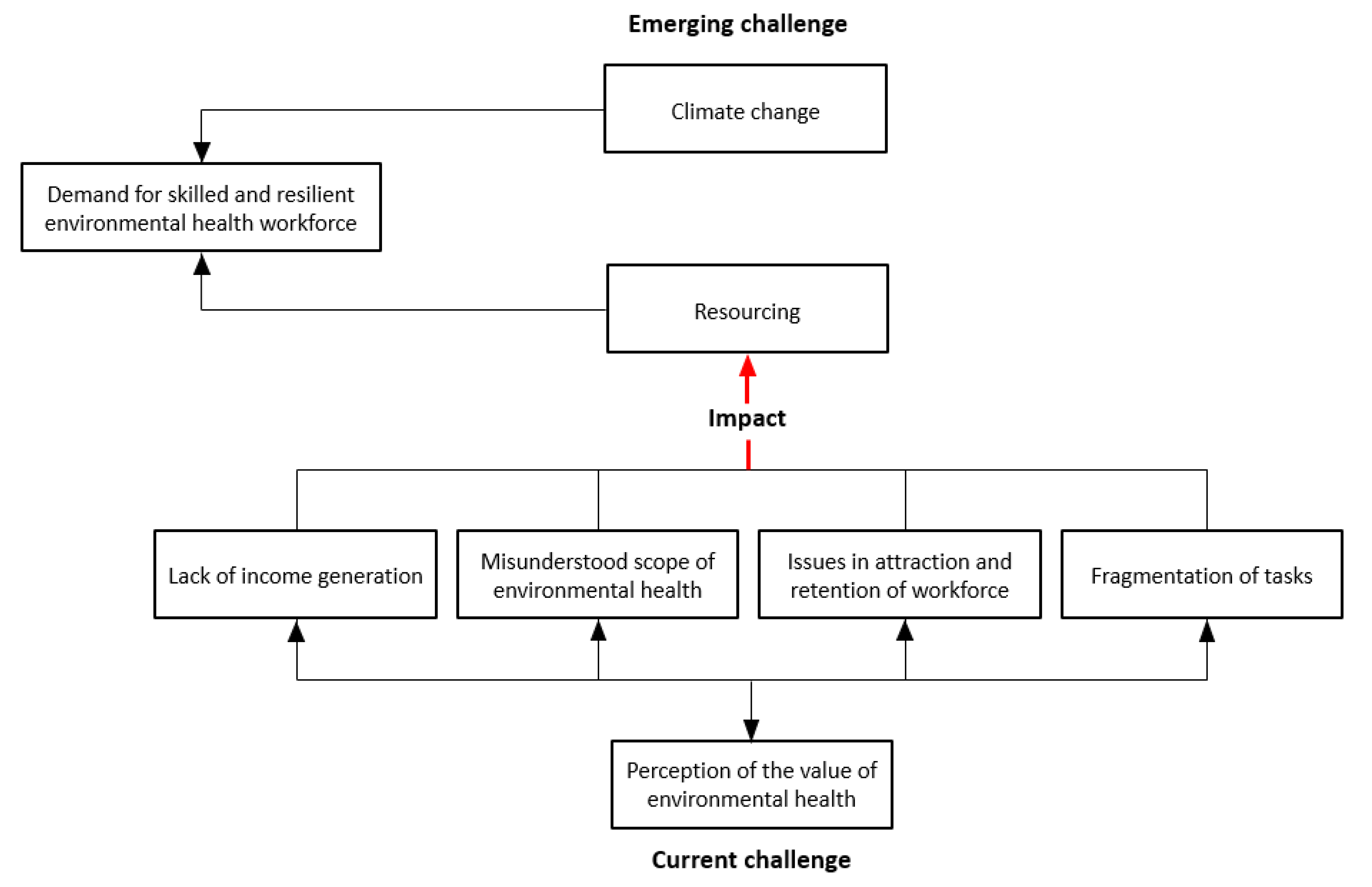

3.2. Survey Results: Workforce Challenges

3.3. Interview Results: Workforce Challenge

3.4. Survey Results: Workforce Response to COVID-19

3.5. Interview Results: Workforce Response to COVID-19

4. Discussion

4.1. Workforce Demographics

4.2. Future Workforce Challenges

4.3. Lessons Learnt from COVID-19

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cop24 Special Report: Health and Climate Change; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9241514973. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, A.J. Earth as humans’ habitat: Global climate change and the health of populations. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 2, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, M.C.; Fox, M.A.; Kaye, C.; Resnick, B. Integrating health into local climate response: Lessons from the us cdc climate-ready states and cities initiative. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 094501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, T.A.; Fox, M.A. Global to local: Public health on the front lines of climate change. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S74–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, P. Cholera is back but the world is looking away. BMJ 2023, 380, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawed, S.; Islam, M.B.; Awan, H.A.; Ullah, I.; Asghar, M.S. Cholera outbreak in balochistan amidst flash floods: An impending public health crisis. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyburn, R.; Kim, D.R.; Emch, M.; Khatib, A.; Von Seidlein, L.; Ali, M. Climate variability and the outbreaks of cholera in zanzibar, east africa: A time series analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Rouse, B.T.; Sarangi, P.P. Did climate change influence the emergence, transmission, and expression of the COVID-19 pandemic? Front. Med. 2021, 8, 769208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Environmental Health. Available online: http://origin.searo.who.int/topics/environmental_health/en/ (accessed on 13 March 2017).

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Overview of Environmental Health. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-envhlth-index.htm (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Environmental Health Committee (enHealth). Preventing Disease and Injury through Healthy Environments: Environmental Health Standing Committee (enHealth) Strategic Plan 2016 to 2020; Endorsed by the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee; Environmental Health Standing Committee (enHealth): Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Environmental Health. National Local Government Environmental Health Workforce Summit. The Changing Landscape of the Environmental Health Workforce in Local Government: Turning Threats into Opportunities; Australian Institute of Environmental Health: Brisbane, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Health Committee (enHealth). Enhealth Environmental Health Officer Skills and Knowledge Matrix; Department of Health and Ageing, Ed.; Environmental Health Committee (enHealth): Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, V.; Smith, J.; Fawkes, S. Public Health Practice in Australia: The Organised Effort, 2nd ed.; Allen & Unwin: Crow’s Nest, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, B.S.; Parker, C.; Glass, T.A.; Hu, H. Global environmental change: What can health care providers and the environmental health community do about it now? Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.C.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.E. Climate change and health: Local government capacity for health protection in australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.Y.; Mathee, A.; Garland, R.M. Climate change, human health and the role of environmental health practitioners. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerding, J.A.; Brooks, B.W.; Landeen, E.; Whitehead, S.; Kelly, K.R.; Allen, A.; Banaszynski, D.; Dorshorst, M.; Drager, L.; Eshenaur, T.; et al. Identifying needs for advancing the profession and workforce in environmental health. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Beggs, P.J.; Bambrick, H.; Berry, H.L.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Trueck, S.; Alders, R.; Bi, P.; Boylan, S.M.; Green, D. The mja–lancet countdown on health and climate change: Australian policy inaction threatens lives. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Health Australia [South Australia]. Environmental Health Workforce Attraction and Retention—Research Paper; Environmental Health Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen, J.; Stoneham, M.; Hannelly, T.; Masaka, E.; Dodds, G.; Andrich, V. Environmental health responses to COVID-19 in western australia: Lessons for the future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Health Australia. Environmental Health Course Accreditation Policy; Environmental Health Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, G.; Smith, J. Environmental health officers and health for all in australia and the united kingdom. Environ. Health Rev. Aust. 1992, 21, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.C.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.E. The new environmental health in australia: Failure to launch? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, I. Roles and Opportunities for the Environmental Health Practitioner in the Next Cntury. Paper Presented to the Australian Institute of Environmental Health (Queensland Branch) Conference, September 1999. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/56578429/Roles_and_opportunities_for_the_environmental_health_practitioner_in_the_next_century-libre.pdf?1526449055=response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DRoles_and_opportunities_for_the_environm.pdfExpires=1689650676Signature=f5RSBvx-jx3a13ZSzFaAbRR~oVAWrBLjq2qophMJmc8B23-AMyo5TCyhsbWFu2Sl5ePftk21fFX1ezsGGu2U6S9EGsTipcJnFZc5FMyItUb9wOvcSoMMg5c~28i7yccISpkwrwGWcO56BANbKeuvzZosuCTOhxPZt9jZHQyigzj7rAAuJrnRRav8RVsFSfQ5hrHPXUBgEih4g3IqN0Y25MLpDiKS17ix~g283im5~bieOohudk9sAZLaSS4FSDakFlzAfpjnv~DyzXg166ttlLL8RsbZfqECciTzVrGfTaU3YW2HJLs13TgKPjWyAgs7Bk0ciuH~56MvMZAw9ol1Bg__Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Ryan, B.J.; Swienton, R.; Harris, C.; James, J.J. Environmental health workforce—Essential for interdisciplinary solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Whiley, H.; Smith, J.C.; Moore, N.; Burton, R.; Conci, N.; Psarras, H.; Ross, K.E. Climate Change and Health: Challenges to the Local Government Environmental Health Workforce in South Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146384

Whiley H, Smith JC, Moore N, Burton R, Conci N, Psarras H, Ross KE. Climate Change and Health: Challenges to the Local Government Environmental Health Workforce in South Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(14):6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146384

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhiley, Harriet, James C. Smith, Nicole Moore, Rebecca Burton, Nadia Conci, Helen Psarras, and Kirstin E. Ross. 2023. "Climate Change and Health: Challenges to the Local Government Environmental Health Workforce in South Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 14: 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146384

APA StyleWhiley, H., Smith, J. C., Moore, N., Burton, R., Conci, N., Psarras, H., & Ross, K. E. (2023). Climate Change and Health: Challenges to the Local Government Environmental Health Workforce in South Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146384