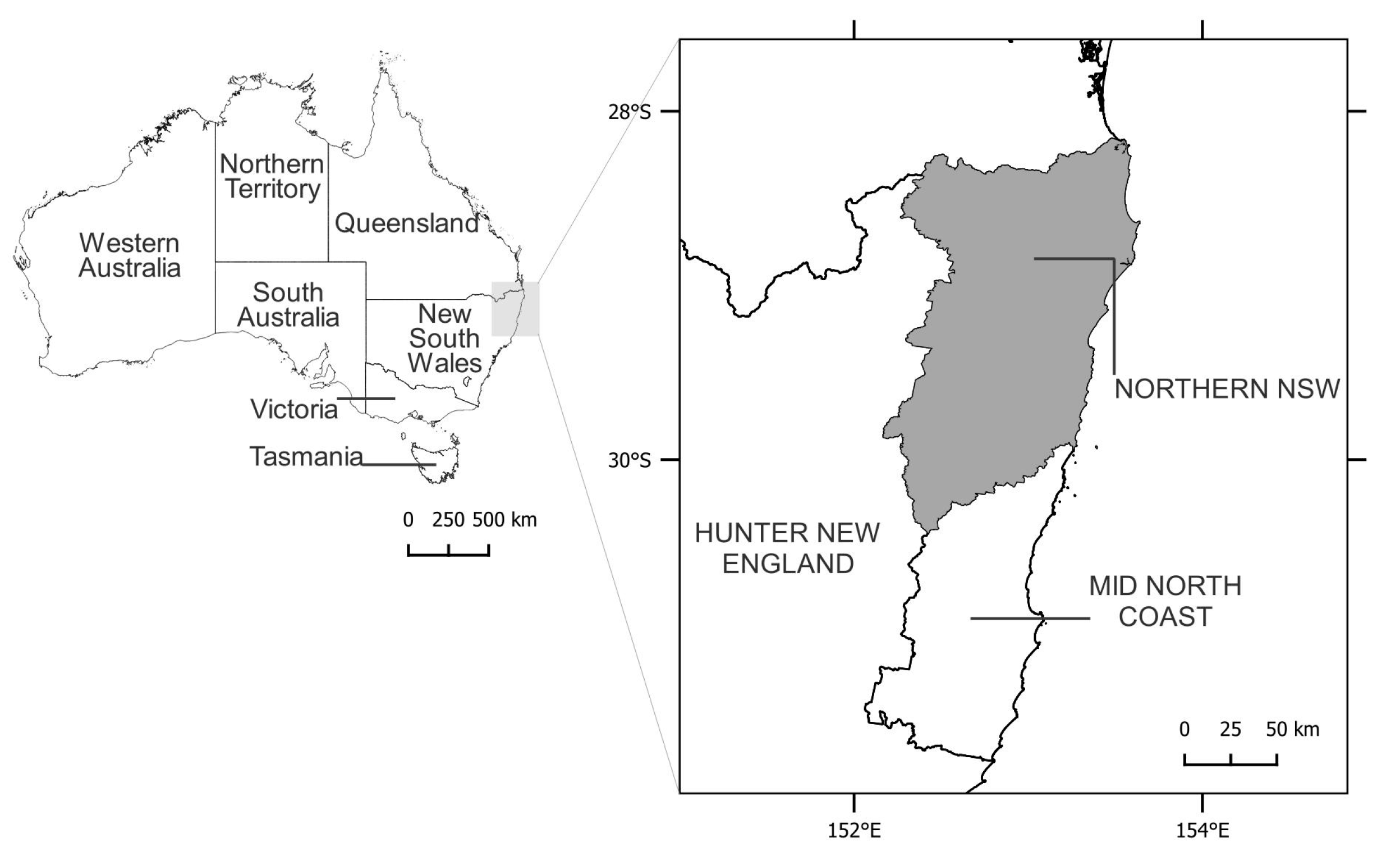

Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Health Services in Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Rapid Review

Abstract

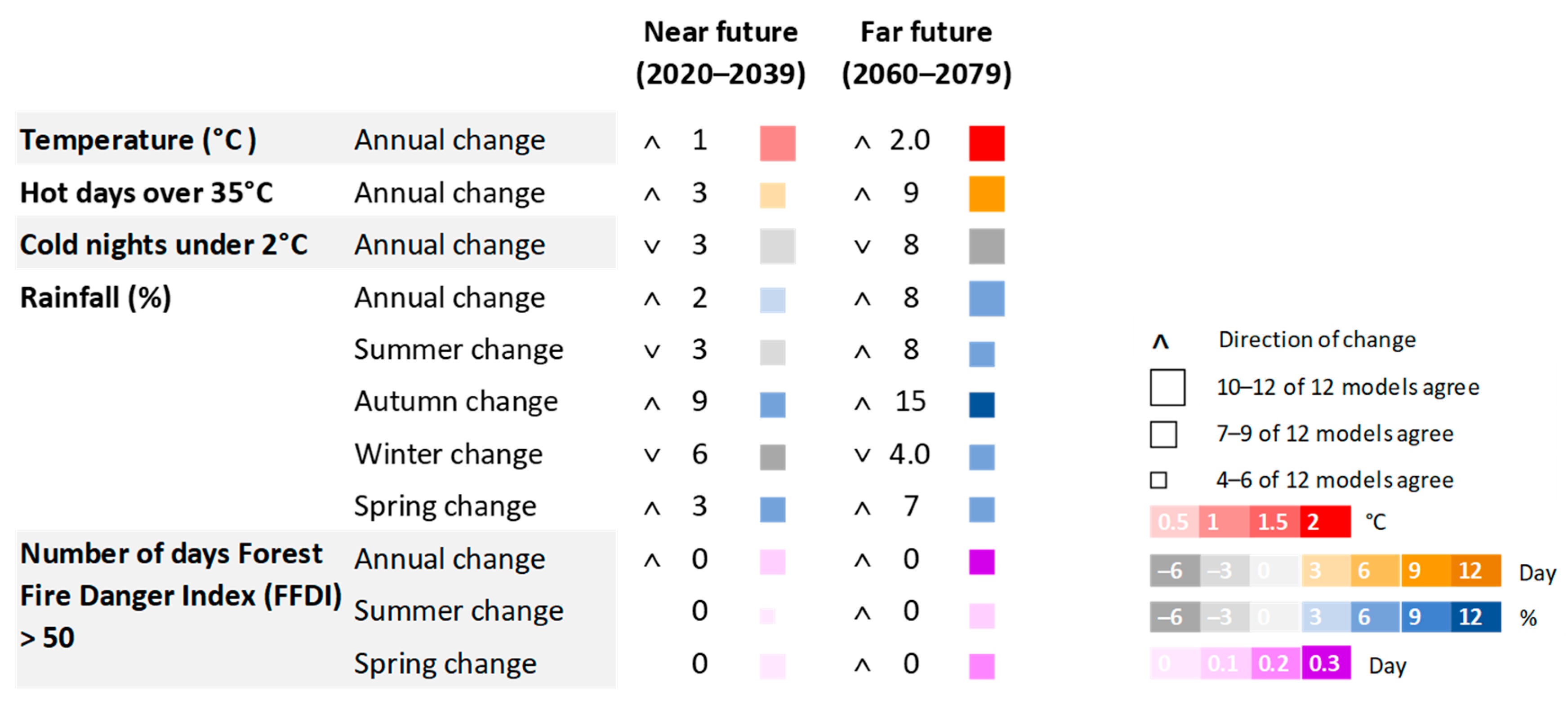

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

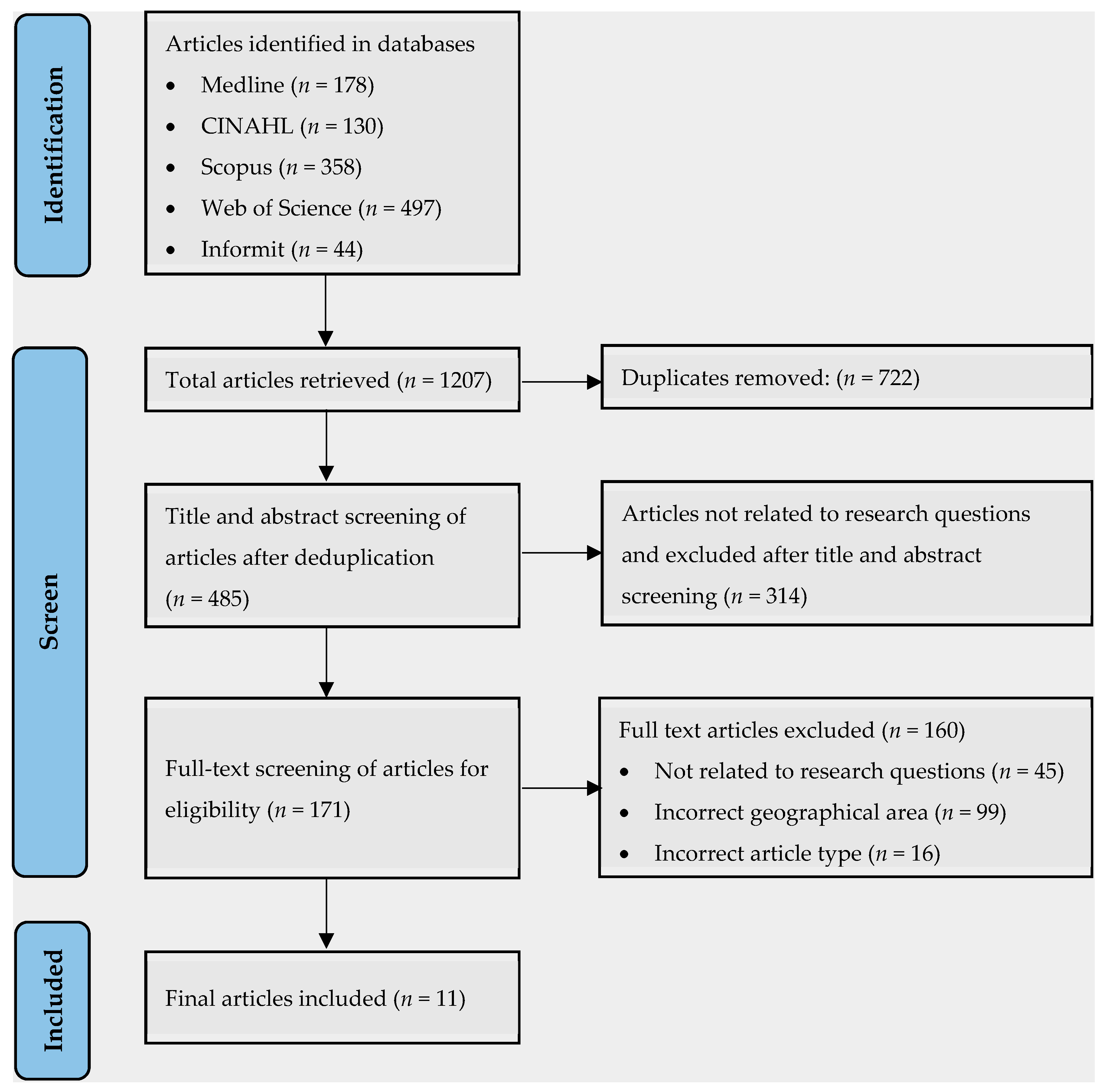

2.4. Screening

2.5. Data Categorisation and Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Articles Selected

3.2. Study Characteristics

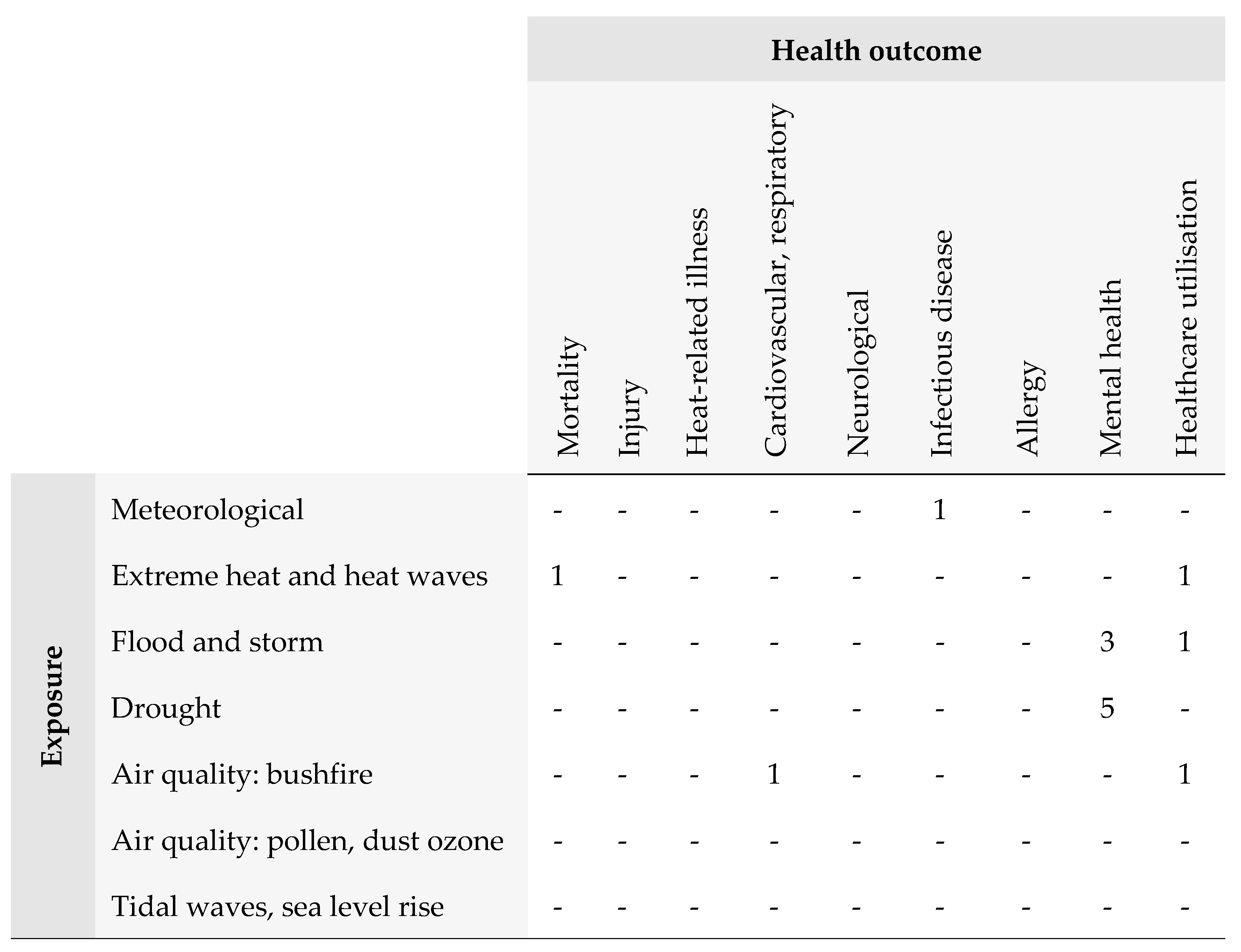

3.3. Research Gaps

3.4. Summary of Findings

3.4.1. Mental Health

3.4.2. Vector Borne Disease

3.4.3. Mortality

3.4.4. Health Services Utilisation

3.5. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Research Gaps

4.3. Research Directions

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Acronyms

Appendix A

| First Author | Year | Title | Location | Population/ Participants | Study Type/Period | Exposure/ Outcome | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austin et al. [38] | 2018 | Drought-related stress among farmers: findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. | NSW non-metropolitan regions (inner regional, outer regional, remote, very remote regions). | Adults living and/or working on a farm (n = 664) aged >18 from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study (ARMHS) Predominately live on farms in inner and outer regional areas. | Longitudinal cohort ARMHS 2007–2013 Generalised Estimating equations model. | Exposure: drought (rainfall deficiency) Outcome: mental health (generalised psychological distress K10 scale, Personal Drought-related Distress (PDS) and Community Drought-related Distress (CDS) Likert scale). | Significant: Compared to those who live on a farm only, those who live and work on a farm were likely to experience PDS (IRR = 1.50; 95% CI: 1.32–1.72). Significant: Compared to female farmers, male farmers were likely to experience elevated general psychological distress. Significant: Compared to older farmers >35, farmers aged 18–35 were likely to experience elevated PDS and CDS. Significant: Compared with farmers from inner regional areas, farmers from outer regional and remote and very remote areas were likely to experience elevated PDS (outer regional IRR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.59–2.23; remote IRR = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.65–2.48); very remote IRR = 2.55, 95% CI: 2.55, 95% CI = 1.97–3.30) and CDS (outer regional IRR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.76–2.38; remote IRR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.83–2.58; very remote IRR = 2.80, 95% CI: 2.26–3.47). Significant: Compared to farmers with comfortable financial status, farmers with lower financial security were likely to experience elevated general psychological distress (IRR = 2.99, 95% CI = 1.52–5.89) and PDS (IRR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.38–2.14). | Application of the meteorological definition of drought may miss out on mental health effects captured by other measures of drought type. Self-reporting of health outcomes can introduce bias and misclassification. |

| Austin et al. [32] | 2020 | Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. | NSW non-metropolitan regions (inner regional, outer regional, remote, and very remote regions). | Adults from non-metropolitan NSW (n = 823) Age > 18 ARMHS Participants. | Open-ended questionnaire. Word frequency test, thematic analysis 2007–2013. | Exposure: drought, climate change Outcome: perspectives and concerns. | Qualitative: Many respondents believed climate change was natural and not caused by human actions. Key concerns were the financial, environmental (particularly water insecurity), and health and social impacts. Both governments’ inaction to mitigate climate change and the cost of such actions were of concern. | Analysis of free text based on an open-ended questionnaire may not capture in-depth opinions. |

| Bailie et al. [35] | 2022 | Exposure to risk and experiences of river flooding for people with disability and carers in rural Australia: a cross-sectional survey. | Northern NSW (6 Local Government Areas: Ballina Shire, Tweed Shire, Richmond Valley, Kyogle, Byron Shire, and Lismore City). | Adults (n = 2252) Age > 16 Predominately female, aged >45; People with disability (n = 165); Carers (n = 91). | Snowball, cross-sectional survey, 6 months post-flood event in 2017. | Exposure: flood event Outcome: mental health. | Significant: Compared to other respondents, the odds of having homes flooded were elevated for people with disability (OR = 2.41, 95% CI: 1.71–3.39) or carers (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.10–2.84). The odds of having to evacuate and be displaced for more than 6 months were elevated for people with disability (OR = 3.78, 95% CI: 2.18–6.55). The odds of not getting timely help or access to health and social services were elevated for people with disability (OR = 3.98%, 95% CI = 2.82–5.60). Significant: Compared to other respondents, the odds of experiencing probable PTSD elevated for carers or people with disability (OR = 3.32, 95% CI: 2.22–4.96). | Limited generalisability. Difficult to establish causation. Self-reporting of mental health conditions can introduce bias and misclassification. |

| Hanigan et al. [39] | 2012 | Suicide and drought in New South Wales, Australia, 1970–2007. | NSW (11 rural or urban regions, including Northern NSW. | Age > 10 by males and females. | Time series 1970–2007 Poisson generalised additive model. | Exposure: drought (Hutchinson Drought Severity Index HDSI) Outcome: suicides. | Significant: Increase in relative risk of suicide by 15% (95% CI: 8–22%) in rural males aged 30–49 years per the first to third quartile increase in the HDSI. The predicted annual suicides in this subgroup was 4 (95% CI: 2.14–6.05) or 9% of the total number in the age group). Significant: Decrease in relative risk of suicide for rural females aged 30–49 (RR = −0.72, 95% CI: −0.31 to −0.01). No association between drought and suicide in urban populations. | Likely underestimation of historical suicide risk in farmers. |

| Hanigan et al. [42] | 2022 | Climate Change, Drought, and Rural Suicide in New South Wales, Australia: Future Impact Scenario Projections to 2099. | NSW (11 rural or urban regions, including Northern NSW. | Age > 10 by males and females. | Modelling Baseline: 1970–1999; Projection: 2000–2099. | Exposure: drought (HDSI) Outcome: suicides. | Significant: Compared to the attributable number (AN) of excess suicides per annum in drought for rural males aged 30–49 in the historical period, an 84% increase (95% CI: 2–159) was projected under the driest scenario RCP 4.5 (AN = 1.5, 95% CI: 0.84–2.13). Significant: Decrease in AN of excess suicides per annum in drought for rural females aged 30–49 between historical (AN = −0.29, 95% CI: −0.61 to −0.03) and projected (AN = −0.53, 95% CI: −1.14 to −0.05) period. Significant: Elevated gender differences in AN of excess suicides per annum in drought between rural males and females aged 30–49 in the projected period (AN = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.98–2.18). No gender difference in drought-related suicide rates in urban populations. | Limited assessment of regional patterns in the modelled climate data may introduce exposure misclassification bias. Did not consider the effect of temperature on suicide. |

| Hime et al. [34] | 2022 | Weather extremes associated with increased Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus notifications in NSW: learnings for public health response. | NSW east coast/northeast NSW (4 major population centres on central, mid-north, and north coast of NSW). | NSW residents of northeast NSW. | Ecological Descriptive analysis February 2020. | Exposure: High rainfall, high tides, high mosquito counts Outcome: RRV/BFV detections and Human RRV/BFV notifications. | Descriptive: Following two extremely dry years and after a significant rainfall event and high tides in February 2020, there was a substantial increase in mosquito abundance occurred after 2 weeks, followed by RRV and BFV notifications in northeast NSW after 8 and 9 weeks, respectively. Mosquito bite avoidance messaging should be instigated within 2 weeks of high summer rainfall, especially after an extended dry period. | Environmental, entomological, and epidemiological events may not necessarily be linked. Underestimation of human infections by surveillance system due to asymptomatic infections. |

| Jagasothy et al. [40] | 2017 | Extreme climatic conditions and health service utilisation across rural and metropolitan New South Wales. | NSW (3 regions: major cities, inner regional and outer regional /remote/very remote areas). | NSW residents. | Time-series 2005–2015 Poisson regression model. | Exposure: Cold wave, heat wave Outcome: mortality, ambulance callouts, and emergency department (ED) presentations. | Significant: A positive dose–response relationship was observed between the severity of heat waves and ambulance callouts in each study region. Significant: Compared with a non-heat wave days, incidence rate ratio (IRR) of ambulance call-outs were elevated in NSW after low-intensity (IRR = 1.018, 95% CI: 1.015–1.022), intense (IRR = 1.047, 95% CI: 1.039–1.056) and very intense (IRR = 1.109, 95% CI: 1.077–1.142) heat waves. This was also the case for each study region. Significant: ED presentations were also elevated in NSW after low-intensity (IRR = 1.009, 95% CI: 1.004–1.014) and intense (IRR = 1.036, 95% CI: 1.024–1.048) heat waves. Significant: Mortality was elevated after intense (IRR = 1.024; 95% CI: 1.008–1.041) and very intense (IRR = 1.108; 95% CI: 1.045–1.174) heat waves for NSW. This is also the case for major cities. This maybe due to the urban heat island effect. Significant: ED presentations were elevated after low (IRR = 1.047; 95% CI: 1.042–1.052); intense (IRR = 1.093; 95% CI: 1.080–1.106) and very intense (IRR = 1.082; 95% CI: 1.050–1.116) cold waves in outer regional/remote/very remote areas. | |

| King et al. [36] | 2020 | Disruptions and mental health outcomes following Cyclone Debbie. | Northern NSW (6 Local Government Areas: Ballina Shire, Tweed Shire, Richmond Valley, Kyogle, Byron Shire, and Lismore City). | Adults (n= 2180) Age > 16 Predominately female, aged >45; Direct disruption (n = 1228); Indirect disruption (n = 605). | Snowball, cross-sectional survey, 6 months post-flood event in 2017. | Exposure: flood event Outcome: Mental health, loss of access to social/health care, food, and utilities. | Significant: Compared to non-disrupted respondents, odds of experiencing distress (OR = 3.31; 95% CI: 1.79–6.12), probable PTSD (OR = 13.48; 95% CI: 5.45–33.35), depression (OR = 4.26; 95% CI: 2.35–7.73), anxiety (OR = 3.64; 95% CI: 1.74–7.62), and suicidal ideation (OR = 2.86; 95% CI: 1.36–5.99) were elevated for directly disrupted respondents. Mental health outcomes of indirectly disrupted respondents were less severe, but the odds of experiencing probable PTSD (OR = 3.52, 95% CI: 1.36–9.15) were still elevated. Significant: Compared to non-disrupted respondents, odds of experiencing distress (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.38–2.49), probable PTSD (OR = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.38–2.7), anxiety (OR = 2.67, 95% CI: 1.64–4.35) and suicidal ideation (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.14–2.66) were elevated for those who lost access to social services/healthcare. | Limited generalisability. Difficult to establish causation. Self-reporting of mental health conditions can introduce bias and misclassification. |

| Matthews et al. [37] | 2019 | Differential mental health impact six months after extensive river flooding in rural Australia: A cross-sectional analysis through an equity lens. | Northern NSW (6 Local Government Areas: Ballina Shire, Tweed Shire, Richmond Valley, Kyogle, Byron Shire, and Lismore City). | Adults (n= 2180) Age > 16 Predominately female, aged 35–74. | Snowball, cross-sectional survey, 6 months post-flood event in 2017. | Exposure: flood event Outcome: mental health. | Significant: Compared to unexposed respondents, odds of experiencing distress (OR = 25.70, 99% CI: 9.20–71.81), probable PTSD(OR = 24.43, 99% CI: 7.05–84.69), anxiety (OR = 14.50, 99% CI: 5.15–40.85), and depression (OR = 8.38, 99% CI: 3.04–23.10) were elevated for respondents who were displaced after 6 months. This was also the case for those whose homes/businesses/farms were evacuated/flooded. Significant: Odds of experiencing probable anxiety (OR = 2.16, 99% CI: 1.08–4.33) and depression (OR = 2.09, 99% CI: 1.04–4.23) were elevated for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. This was also the case for income support recipients’ respondents (anxiety OR = 1.89, 99% CI: 1.26–2.85; depression OR = 1.84, 99% CI: 1.22–2.79). | Limited generalisability. Difficult to establish causation. Self-reporting of mental health conditions can introduce bias and misclassification. |

| Ng et al. [33] | 2015 | Climate adversity and resilience: the voice of rural Australia. | NSW (2 regional centres, 2 rural villages). | Adults who experienced drought and flood within 5 years Age > 18 (n = 46). | In-depth focus groups and interviews Purposive and convenience sampling. | Exposure: drought and flood Outcome: experience, health, and wellbeing. | Qualitative: Flood and drought contributed to emotional stress and anxiety due to fear about the reoccurrence of the disasters, financial loss; loss of possession; loss of status, family heritage, generational history, and rural community structure; loss of material procession; loss of physical infrastructure. Social connectedness can promote resilience in disaster-struck rural communities. | Limited generalisability of research findings to the broader rural population due to differences in climate, farming practices, community, and rural culture. |

| Wen et al. [41] | 2022 | Excess emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases during the 2019–2020 bushfire period in Australia: A two-stage interrupted time-series analysis. | NSW (28 Statistical Area 4 regions in NSW). | NSW residents. | Time-series Two-stage interrupted analysis 2019–2020 bushfire period. | Exposure: Bushfire event Outcome: respiratory and cardiovascular-related ED visits. | Significant: Compared to the same periods of 2017–2018 and 2018–2019, the relative risk (RR) of excess ED visits for respiratory (RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.09) and cardiovascular diseases (RR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.07–1.13) were elevated during the 2019–2020 bushfires. Significant: The RR of excess respiratory -related ED visits were elevated in low SES regions compared to high SES regions (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.06–1.18); and in regions of high fire intensity compared to low fire intensity. For cardiovascular-related ED visits, no significant difference was found when stratified by SES and fire intensity. | Outcome classification maybe introduced in diagnostic outcome data as they were not coded by clinicians. |

| Author, Year, Title | Level of Evidence | Consistency of Evidence | Clinical Impact | Risk of Bias | Generalisability and Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austin et al., 2018 [38] Drought-related stress among farmers: findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. | Level III-2 * | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Very large | Moderate | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Bailie et al., 2022 [35] Exposure to risk and experiences of river flooding for people with disability and carers in rural Australia: a cross-sectional survey. | Level III-2 * | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Very large | High | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Hanigan et al., 2012 [39] Suicide and drought in New South Wales, Australia, 1970–2007. | Level III-2 * | Consistent with other studies. | Moderate | Moderate | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Hanigan et al., 2022 [42] Climate Change, drought and rural suicide in New South Wales, Australia: Future impact scenario projections to 2099. | Level III-2 * | Consistent with other studies The authors discussed in detail the similarity with other study findings and with the findings from their previous studies. | Moderate | Moderate | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Hime et al., 2022 [34] Weather extremes associated with increased Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus notifications in NSW: learnings for public health response. | Level III-2 * | Consistent with other studies. | Very large | Moderate | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Jagasothy et al., 2017 [40] Extreme climatic conditions and health service utilisation across rural and metropolitan New South Wales. | Level III-2 ** | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Very large | Low | Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| King et al., 2020 [36] Disruptions and mental-health outcomes following Cyclone Debbie. | Level III-3 ** | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Very large | High | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Matthews et al., 2019 [37] Differential Mental Health Impact Six Months After Extensive River Flooding in Rural Australia: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Through an Equity Lens. | Level III-2 * | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Very large | Moderate | Population/s studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Wen et al., 2022 [41] Excess emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases during the 2019–2020 bushfire period in Australia: A two-stage interrupted time-series analysis. | Level III-2 * | Mostly consistent with other studies and inconsistency may be explained. | Moderate | Low | Populations studied in body of evidence are the same as the target population in question. Directly applicable to Australian healthcare context. |

| Author, Year, Title | Level of Evidence | Risk of Bias | Evidence for Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austin et al., 2020 [32] Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. | Level 3 Descriptive studies | Do not report full range of responses. | Demonstrate that a phenomenon exists in a defined group. Identify practice issues for further consideration. |

| Ng et al., 2015 [33] Climate adversity and resilience: the voice of rural Australia. | Level 3 Descriptive studies | Do not report full range of responses. | Demonstrate that a phenomenon exists in a defined group. Identify practice issues for further consideration. |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; in press; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation & the Bureau of Meteorology. State of the Climate 2022; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.csiro.au/en/research/environmental-impacts/climate-change/state-of-the-climate (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Regional Fact Sheet—Australiasia. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/factsheets/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Regional_Fact_Sheet_Australasia.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; Lee, M.; et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beggs, P.J.; Zhang, Y.; McGushin, A.; Trueck, S.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Bambrick, H.; Capon, A.G.; Vardoulakis, S.; Green, D.; Malik, A.; et al. The 2022 report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Australia unprepared and paying the price. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 217, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heenan, M.; Rychetnik, L.; Howse, E.; Beggs, P.J.; Weeramanthri, T.S.; Armstrong, F.; Zhang, Y. Australia’s political engagement on health and climate change: The MJA–Lancet Countdown indicator and implications for the future. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 218, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Local Health District Boards and Specialty Network Boards. NSW Health; 6 June 2022. Available online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/lhd/boards/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Rychetnik, L.; Sainsbury, P.; Stewart, G. How Local Health Districts can prepare for the effects of climate change: An adaptation model applied to metropolitan Sydney. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.; Kiem, A.S.; Rich, J.; Perkins, D.; Kelly, B. How effectively do drought indices capture health outcomes? An investigation from rural Australia. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 13, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why Can Floods Like Those in the Northern Rivers Come in Clusters? The Conversation; 31 March 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-can-floods-like-those-in-the-northern-rivers-come-in-clusters-180250 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- State of NSW and Department of Planning Industry and Environment. NSW Fire and the Environment 2019–20 Summary; DPIE: Sydney, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Parks-reserves-and-protected-areas/Fire/fire-and-the-environment-2019-20-summary-200108.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Climate Projections Used on AdaptNSW. NSW Government: Sydney, Australia. Available online: https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/climate-projections-used-adaptnsw (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Emissions Scenarios; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/emissions_scenarios-1.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Office of the Environment & Heritage. North Coast Climate Change Snapshot; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2014. Available online: https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/North%20Coast%20climate%20change%20snapshot.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Dowdy, A.; Abbs, D.; Bhend, J.; Chiew, F.; Church, J.; Ekström, M.; Kirono, D.; Lenton, A.; Lucas, C.; McInnes, K.; et al. Climate Change in Australia Projections Cluster Report: East Coast; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and Bureau of Meteorology: Canberra, Australia, 2015. Available online: https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/media/ccia/2.2/cms_page_media/168/EAST_COAST_CLUSTER_REPORT_2021updated.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Office of Environment & Heritage. Integrated Regional Vulnerability Assessment: North Coast of New South Wales (Volume 1 Assessment Report); NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2016. Available online: https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/IRVA%20North%20Coast%20Vol%201.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Projections Explorer. Department of Planning and Environment. Available online: https://pp.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/populations (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 27 March 2018. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~IRSD%20Interactive%20Map~15 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Australian Bureau of Statistics; June 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/search-by-area (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Healthy Environments and Lives (HEAL) Network & Centre for Research Excellence. Climate Change and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, Discussion Paper; Lowitja Institute: Collingwood, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Image/Lowitja_ClimateChangeHealth_1021_D10.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- PRISMA for Scoping Reviews. Available online: http://prisma-statement.org/Extensions/ScopingReviews (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Beggs, P.J.; Zhang, Y.; Bambrick, H.; Berry, H.L.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Trueck, S.; Bi, P.; Boylan, S.M.; Green, D.; Guo, Y.; et al. The 2019 report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: A turbulent year with mixed progress. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 490–491.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, E.G.; McIver, L.J. Climate change: A brief overview of the science and health impacts for Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change and Health. World Health Organisation; 30 October 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Parise, I. A brief review of global climate change and the public health consequences. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocque, R.J.; Beaudoin, C.; Ndjaboue, R.; Cameron, L.; Poirier-Bergeron, L.; Poulin-Rheault, R.-A.; Fallon, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Witteman, H.O. Health effects of climate change: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.M. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on climate change and human health with an emphasis on infectious diseases. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2009. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/images/NHMRC%20Levels%20and%20Grades%20(2009).pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Daly, J.; Willis, K.; Small, R.; Green, J.; Welch, N.; Kealy, M.; Hughes, E. A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, E.K.; Rich, J.L.; Kiem, A.S.; Handley, T.; Perkins, D.; Kelly, B.J. Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 75, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.Y.; Wilson, L.A.; Veitch, C. Climate adversity and resilience: The voice of rural Australia. Rural. Remote Health 2015, 15, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hime, N.J.; Wickens, M.; Doggett, S.L.; Rahman, K.; Toi, C.; Webb, C.; Vyas, A.; Lachireddy, K. Weather extremes associated with increased Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus notifications in NSW: Learnings for public health response. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 19, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, J.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Villeneuve, M.; Longman, J. Exposure to risk and experiences of river flooding for people with disability and carers in rural Australia: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Longman, J.; Matthews, V.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Bailie, R.S.; Carrig, S.; Passey, M. Disruptions and mental-health outcomes following Cyclone Debbie. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2020, 35, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Berry, H.L.; Passey, M.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Morgan, G.G.; Pit, S.; Rolfe, M.; Bailie, R.S. Differential mental health impact six months after extensive river flooding in rural Australia: A cross-sectional analysis through an equity lens. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.K.; Handley, T.; Kiem, A.S.; Rich, J.L.; Lewin, T.J.; Askland, H.H.; Askarimarnani, S.S.; Perkins, D.A.; Kelly, B.J. Drought-related stress among farmers: Findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigan, I.C.; Butler, C.D.; Kokic, P.N.; Hutchinson, M.F. Suicide and drought in New South Wales, Australia, 1970–2007. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13950–13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegasothy, E.; McGuire, R.; Nairn, J.; Fawcett, R.; Scalley, B. Extreme climatic conditions and health service utilisation across rural and metropolitan New South Wales. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Wu, Y.; Xu, R.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Excess emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases during the 2019–20 bushfire period in Australia: A two-stage interrupted time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 152226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigan, I.C.; Chaston, T.B. Climate change, drought and rural suicide in New South Wales, Australia: Future impact scenario projections to 2099. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standen, J.C.; Spencer, J.; Lee, G.W.; Van Buskirk, J.; Matthews, V.; Hanigan, I.; Boylan, S.; Jegasothy, E.; Breth-Petersen, M.; Morgan, G.G. Aboriginal population and climate change in Australia: Implications for health and adaptation planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau of Meteorology. Special Climate Statement 76—Extreme Rainfall and Flooding in South-Eastern Queensland and Eastern New South Wales; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2022. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/statements/scs76.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Department of Premier and Cabinet. 2022 Flood Inquiry: Full Report; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2022-08/VOLUME_TWO_Full%20report.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Askland, H.H.; Shannon, B.; Chiong, R.; Lockart, N.; Maguire, A.; Rich, J.; Groizard, J. Beyond migration: A critical review of climate change induced displacement. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 8, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury Hall, N.; Crosby, L. Climate change impacts on health in remote indigenous communities in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Webb, L. Climate change, health and well-being in Indigenous Australia. In Health of People, Places and Planet. Reflections Based on Tony McMichael’s Four Decades of Contribution to Epidemiological Understanding; Butler, C.D., Dixon, J., Capon, A.G., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Whitehead, P.J. Healthy Country: Healthy People? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2005, 29, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Bambrick, H.; Su, H.; Tong, S.; Hu, W. Impacts of heat, cold, and temperature variability on mortality in Australia, 2000–2009. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2558–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigan, I.C.; Dear, K.B.G.; Woodward, A. Increased ratio of summer to winter deaths due to climate warming in Australia, 1968–2018. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 504–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.S.G.; Dewan, A.; Botje, D.; Shahid, S.; Hassan, Q.K. Vulnerability of Australia to heatwaves: A systematic review on influencing factors, impacts, and mitigation options. Environ. Res. 2022, 213, 113703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.M.; Pringle, K.J.; Pope, R.J.; Arnold, S.R.; Conibear, L.A.; Burns, H.; Rigby, R.; Borchers-Arriagada, N.; Butt, E.W.; Kiely, L.; et al. Impact of the 2019/2020 Australian megafires on air quality and health. Geohealth 2021, 5, e2021GH000454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.M.; Schneider-Futschik, E.K.; Knibbs, L.D.; Irving, L.B. Health impacts of bushfire smoke exposure in Australia. Respirology 2020, 25, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Jalaludin, B.B.; Morgan, G.G.; Hanigan, I.C.; Johnston, F.H. Bushfire smoke: Urgent need for a national health protection strategy. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 212, 349–353.e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tall, J.A.; Gatton, M.L.; Tong, S. Ross River Virus disease activity associated with naturally occurring nontidal flood events in Australia: A systematic review. J. Med. Entomol. 2014, 51, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.; Coates, L.; van den Honert, R.; Gissing, A.; Bird, D.; Dimer de Oliveira, F.; D’Arcy, R.; Smith, C.; Radford, D. Exploring the circumstances surrounding flood fatalities in Australia—1900–2015 and the implications for policy and practice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.; Handmer, J.; McAneney, J.; Tibbits, A.; Coates, L. Australian bushfire fatalities 1900–2008: Exploring trends in relation to the ‘Prepare, stay and defend or leave early’ policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Waters, E.; Gibbs, L.; Gallagher, H.C.; Pattison, P.; Lusher, D.; MacDougall, C.; Harms, L.; Block, K.; Snowdon, E.; et al. Psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, T.; Stephens, R.; Dominey-Howes, D.T.M.; Bruce, E.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. Disaster declarations associated with bushfires, floods and storms in New South Wales, Australia between 2004 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.P.F.; Amin, J.; Graham, P.L.; Beggs, P.J. Climate variability and change are drivers of salmonellosis in Australia: 1991 to 2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843, 156980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; FitzGerald, G.J.; Clark, M.; Hou, X.-Y. Health impacts of floods. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2010, 25, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.V.; Hanigan, I.C.; Dear, K.B.G.; Vally, H. The influence of weather on community gastroenteritis in Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katelaris, C.H.; Beggs, P.J. Climate change: Allergens and allergic diseases. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Åström, C.; Boyer, C.J.; Harrington, L.J.; Hess, J.J.; Honda, Y.; Kazura, E.; Stuart-Smith, R.F.; Otto, F.E.L. Using detection and attribution to quantify how climate change is affecting health. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Rocklöv, J. Climate change and health modeling: Horses for courses. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 24154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Climate Change and Health Research: Current Trends, Gaps and Perspectives for the Future; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/climate-change-and-health-research-current-trends-gaps-and-perspectives-for-the-future (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Dufty, N. Using heat refuges in heatwave emergencies. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2022, 36, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, G.J.; Capon, A.; Aitken, P. Resilient health systems: Preparing for climate disasters and other emergencies. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hime, N.; Vyas, A.; Lachireddy, K.; Wyett, S.; Scalley, B.; Corvalan, C. Climate change, health and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in NSW, Australia. Public Health Res. Pract. 2018, 28, e2841824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, H.; King, J.C.; Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C. Systematic review of the impact of heatwaves on health service demand in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrey, C.G.A.; Beaton, L.; Kneebone, J.A. General practice in the era of planetary health: Responding to the climate health emergency. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson, K.A.; FitzGerald, G.J.; Lim, D. Disaster management in rural and remote primary health care: A scoping review. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.S.; Hu, W.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Barratt, A.L.; Chu, C. Building resilience to Australian flood disasters in the face of climate change. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 217, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppermann, E.; Brearley, M.; Law, L.; Smith, J.A.; Clough, A.; Zander, K. Heat, health, and humidity in Australia’s monsoon tropics: A critical review of the problematization of ‘heat’ in a changing climate. Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, e468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.H.; Foster, T.; Hall, N.L. The relationship between infectious diseases and housing maintenance in Indigenous Australian households. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.J.; Skinner, A.; Williamson, A.B.; Fernando, P.; Wright, D. Housing conditions associated with recurrent gastrointestinal infection in urban Aboriginal children in NSW, Australia: Findings from SEARCH. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Concept | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Climate change | (exp climate change/OR (climate change * or global warm * or sea level ris *).mp.) AND (cyclonic storms/OR (cyclon * or storm *).mp. OR droughts/OR drought *.mp. OR floods/OR flood *.mp. OR lightning/OR lightning.mp. OR rain/OR (rain * or extreme rain *).mp. OR tidal waves/OR tid * wave *.mp. OR exp natural disasters/OR (natural disaster * or landslide * or wildfire * or bushfire * or landscape fire or fire storm * or tornado *).mp. OR air pollutants/OR (air pollutant * or particulate matter or dust or pollen or ozone).mp. OR air pollution/OR air pollution.mp. OR exp temperature/OR (hot temperature or heat wave or extreme heat).mp. OR extreme weather/OR extreme weather.mp. OR humidity/OR humid *.mp.) AND |

| Human health and | exp health/OR health.mp. OR health equity/OR health equity.mp. OR disease/OR (disease * or cardiovascular or respiratory).mp. OR exp mortality/OR (mortal * or death or premature death or fatal *).mp. OR mental health/OR (mental health or well?being).mp. OR anxiety/OR anxiety.mp. OR depression/OR depress *.mp. OR exp heat stress disorders/OR (heat stress or heat stroke * or heat?related illness * or heat exhaustion).mp. OR exp vector borne diseases/OR (vector?borne disease * or mosquito?borne disease * or arbovirus infection *).mp. OR |

| Health services | exp “health care facilities, manpower, and services”/OR (health service * or community health * or (emergency adj2 service *) or mental health service * or rural health or regional health or urban health or aboriginal health or general practice or public health).mp. OR (workforce * or health infrastructure or supply chain * or transport or health plan *).mp. OR “health services needs and demand”/OR (health * adj3 demand *).mp. OR health servic *.mp. OR Ambulatory care/OR (ambulatory care or ambulance *).mp. OR disasters/or disaster planning/or emergencies/or emergency shelter/OR (disaster * or disaster plan * or emergenc * or emergency shelter *).mp. AND |

| Australia and Northern NSW | exp Australia/OR (Australia * or New South Wales or Northern Territory or Western Australia or South Australia or Victoria or Tasmania or Queensland or Australian Capital Territory or Torres Strait Island *).mp. OR New South Wales/OR (New South Wales or NSW or local government or “Northern New South Wales Local Health District” or “Northern New South Wales” or Northern New South Wales or east coast or north coast or Northern Rivers or Lismore).mp. |

| Characteristics | Number (n = 11) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Qualitative | 2 | [32,33] |

| Descriptive | 1 | [34] | |

| Cross-sectional | 3 | [35,36,37] | |

| Longitudinal cohort | 1 | [38] | |

| Time-series | 3 | [39,40,41] | |

| Detection and attribution model | 1 | [42] | |

| Location | State level with a focus on regional areas | 8 | [32,33,34,38,39,40,41,42] |

| Northern NSW | 3 | [35,36,37] | |

| Climate exposure | Meteorological | 1 | [34] |

| Extreme heat and heat wave | 1 | [40] | |

| Flood | 3 | [35,36,37] | |

| Drought | 5 | [32,33,38,39,42] | |

| Bushfire and air quality | 1 | [41] | |

| Health outcome | All-cause mortality | 1 | [40] |

| Infectious diseases (vector-, food-, water-borne) | 1 | [34] | |

| Respiratory, cardiovascular | 1 | [41] | |

| Mental health | 8 | [32,33,35,36,37,38,39,42] | |

| Health system | Health services | 3 | [35,40,41] |

| Health Outcome | n | Climate Exposure | Location | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | 8 | Flood and storm | Northern NSW | Cross-sectional analyses found that the 2017 flood event in Northern NSW was associated with probable post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression, particularly for people whose homes, businesses, and farms were inundated, displaced [37], and particularly for marginalised communities (e.g., people with a disability) [35,36]. The disruption of access to healthcare and social services due to floods was also associated with probable PTSD [36]. |

| Drought | NSW with a regional focus | A time series analysis found an association between drought and increased risk of suicide in the period of 1970–2007, particularly for male farmers from rural regions of NSW [39]. Modelling of future climate scenarios found that an increase in the duration and intensity of droughts will increase suicide rates among males in rural NSW between 2000–2099 [42]. A longitudinal study found that younger farmers that experienced the Millennium Drought of 1997–2010 in regional NSW were more likely to report drought-related stress [38]. Qualitative studies found that concerns for the environmental, financial, health and social impacts of climate change may impact the mental health and well-being of rural communities [32,33] | ||

| Health service utilisation | 3 | Flood | Northern NSW | A cross-sectional analysis found that access to healthcare and social services were disrupted during and after the 2017 flood event for affected communities in the Northern Rivers, particularly for people with disabilities and for carers [35]. |

| Heat waves | NSW with a regional focus | A time series study found that heat waves were associated with greater ambulance callouts and emergency department (ED) presentations in the period of 2005–2015 across urban, regional and remote areas of NSW [40]. | ||

| Bushfire | NSW with a regional focus | A time-series study found that the 2019–2020 bushfire elevated the use of ED visits due to cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. Respiratory related-ED visits were elevated in regions of lower socioeconomic status and higher fire densities [41]. | ||

| Vector-borne disease | 1 | Rainfall | Northern NSW | A descriptive study found that Ross River virus (RRV) and Bamah Forest virus (BFV) human disease notifications increased in northeast NSW following a significant rainfall event, high tides, and substantial increase in mosquito abundance in the summer of February 2020 [34]. |

| Mortality | 1 | Heat waves | NSW with a regional focus | A time series analysis found an association between heat waves and mortality across urban, regional, and remote areas of NSW in the period between 2005–2015 [40]. |

| Cardiovascular and respiratory | 1 | Bushfire | NSW with a regional focus | A time-series study found that the 2019–2020 bushfire found increased cardiovascular and respiratory-related ED visits [41]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.W.; Vine, K.; Atkinson, A.-R.; Tong, M.; Longman, J.; Barratt, A.; Bailie, R.; Vardoulakis, S.; Matthews, V.; Rahman, K.M. Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Health Services in Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Rapid Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136285

Lee GW, Vine K, Atkinson A-R, Tong M, Longman J, Barratt A, Bailie R, Vardoulakis S, Matthews V, Rahman KM. Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Health Services in Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Rapid Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136285

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Grace W., Kristina Vine, Amba-Rose Atkinson, Michael Tong, Jo Longman, Alexandra Barratt, Ross Bailie, Sotiris Vardoulakis, Veronica Matthews, and Kazi Mizanur Rahman. 2023. "Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Health Services in Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Rapid Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136285

APA StyleLee, G. W., Vine, K., Atkinson, A.-R., Tong, M., Longman, J., Barratt, A., Bailie, R., Vardoulakis, S., Matthews, V., & Rahman, K. M. (2023). Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Health Services in Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Rapid Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136285