Health and Socioeconomic Determinants of Abuse among Women with Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Aims

3. Data and Methods

Sampling

4. Findings

4.1. Quantitative Analyses

4.1.1. Experienced Abuse: Having Experienced Any Type of Abuse from Their Current or Former Partners

Education Level

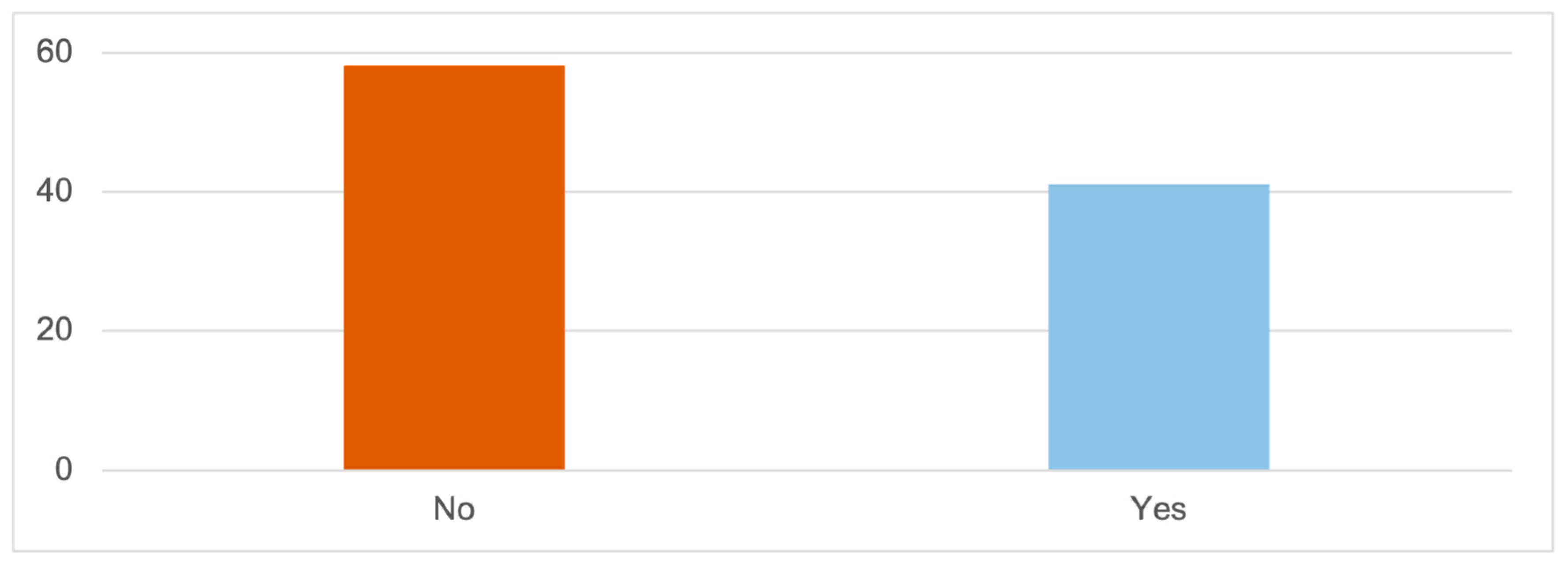

Received Economic Assistance

4.1.2. Physical Abuse: Having Suffered Physical Abuse at the Hands of Their Partners or Ex-Partners

Education Level

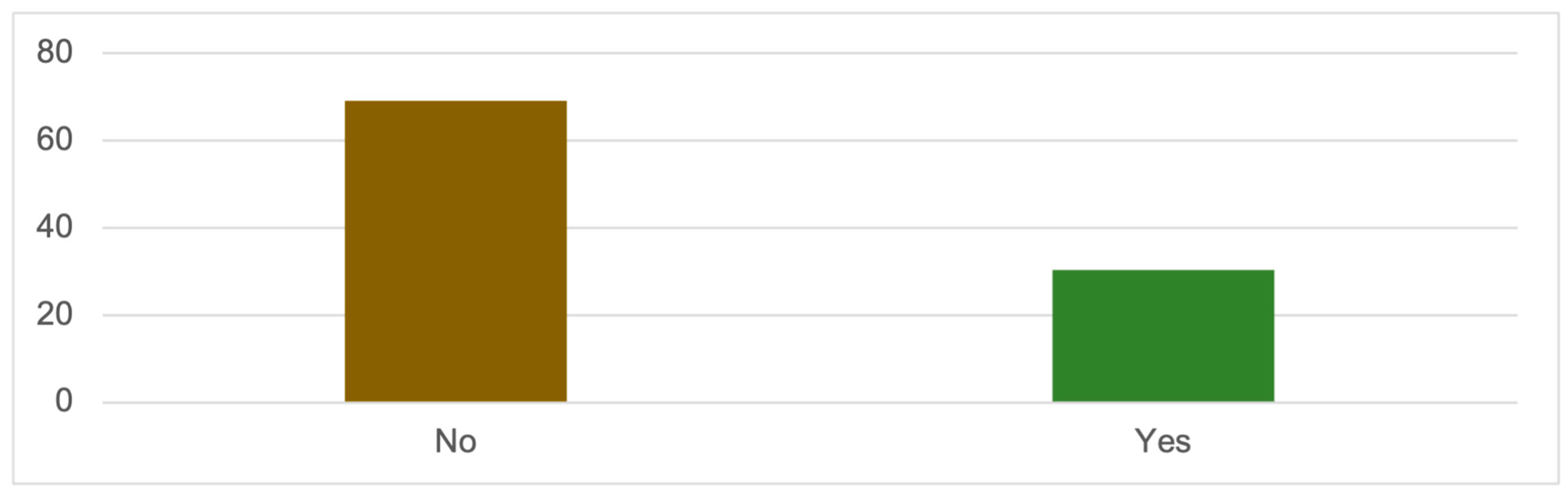

Membership in the Associative Movement

Working Status

4.1.3. Sexual Abuse: Having Experienced Situations of Sexual Abuse by Their Partners or Ex-Partners

Working Status

4.1.4. Other Types of Gender-Based Violence: Having Been Victims of Other Forms of Mistreatment or Aggression (Different from the Previous Ones) Perpetrated by Their Partners or Ex-Partners

4.2. Qualitative Analyses

4.2.1. Face-to-Face Interviews with Women with Disabilities

No, no, it’s me, it’s been since I was 20 when I’ve had any relationship and they’ve told me they wanted to have children… After being abused I’ve suffered, and I don’t want another person to suffer in life because of me. I don’t feel prepared, I don’t feel responsible enough to take care of someone and make them happy. Like I said, I don’t want to bring another unhappy person into the world. I’ve been through such a hard time that I don’t want to repeat it.(M: INT. 13, 47, DO)

Ugh… always, for ten years one after another, one after another, one after another. He was always hitting me. He was always hitting me and talking to me badly. He has always… psychologically, and those things shouldn’t be done.(E: INT. 16, 37, DPsi)

Yes, but I have to have enough economic independence to take care of myself and do what I want at a certain moment, which I’m not doing right now. However, many of them confess to having personal reservations about committing to other partners as a result of previous intimate partner violence, except in cases where the partner has been or is a vital support (when they have not been the ones perpetrating the violence).(M: INT. 1, 32, DPsi)

Included? No, not at all, not at all. You can’t go around saying that you’re an abused woman, that you’ve been abused. It’s like… oh, trauma…, do you understand me?, and it… pushes you away.(M: INT. 5, 48, MU)

Yes, but I need to have enough financial independence to support myself and do what I want at a given moment, which I’m not currently doing.(M: INT. 1, 32, DPsi)

He drank… I saw him drinking because downstairs there was his brother’s bar and every night he was stuck there and he didn’t come out, he didn’t come up to my house until eleven at night and when he went up, he went up really bombed… Our kids woke up when he hit me….(E: INT. 23, 29, DI)

Yes, sometimes I feel insecure. […] Because I have my idiot ex…(S: INT. 3, 25, DI)

But then he would insult me every day.(M: INT. 9, 39, DPsi)

Possessive, anxious, upset. Angry.(M: INT. 4, 29, DI)

Very jealous …He wouldn’t let me talk to my friends or anyone else.(E: INT. 23, 29, DI)

Fear. Fear of that person (perpetrator).(Y: INT. 22, 21, MU)

Yes, I was afraid of my husband, and towards the end, almost afraid of my last partner too.(Y: INT. 19, 57, PM)

4.2.2. Focus Group with Professionals

You have said it, it is that we were made invisible, it is that a few years ago when talking about violence against women, they said no, no…, who is going to harm a woman with disability, who is going to harm a girl with disability?…(P2)

…I have to report…, okay, I have to report and then what…, which resources are there? … which resources do I have? I denounce so what, restraining order?; I have to leave my home?; I have no means, my situation is what it is… okay, but you know you can have support… it’s just that there aren’t steps.(P6)

Abusive caregivers who are caring for people with disabilities, with physical and organic disabilities, with serious mobility problems, and well, they do take care of them…(P4)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bote, M.; Martínez, A.L. Main theoretical approaches to functional diversity: A literature review. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2019, 18, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera, D.; Millán, A.; Sánchez-Mora, M.I. Estrategias de Responsabilidad Social corporativa y Recursos Humanos, para la inclusión laboral de personas con discapacidad. In Aspectos Claves Para a Igualdad en las Relaciones Laborales del Siglo XXI Desde Una Perspectiva Interdisciplinary; Portillo, M.J., Millán, A., Rubio, P.A., Eds.; Aranzadi: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, D. Models of disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 1997, 19, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareño, M.; Masuero, F. La discapacitación social del diferente. Intersicios Rev. Sociol. Pensam. Crít. 2020, 14, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, T. Capabilities and disability: The capabilities framework and the social model of disability. Disabil. Soc. 2004, 19, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo Alonso, M.A. Personas con deficiencias, discapacidades y minusvalías. In Personas Con Discapacidad. Perspectivas Psicopedagógicas y Rehabilitadoras; Verdugo, M.A., Ed.; Siglo Veintiuno: Madrid, Spain, 1995; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo Alonso, M.A. La concepción de la discapacidad en los modelos sociales. In Investigación, Innovación y Cambio. V Jornadas Científicas de Investigación Sobre Personas Con Discapacidad; Verdugo, M.A., Jordán de Urríes, F.B., Eds.; Amarú: Salamanca, Spain, 2003; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, A.S.; Pagani, M.; Meucci, P. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model in mental health: A research critique. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 91, S173–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare, T.; Watson, N.; Alghaib, O.A. Blaming the victim, all over again: Waddell and Aylward’s biopsychosocial (BPS) model of disability. Crit. Soc. Policy 2017, 37, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud; Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento; la Discapacidad y la Salud (CIF). Programa Docente y de Difusión; Instituto Nacional de Servicios Sociales: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, A.; Romañach, J. El Modelo de la Diversidad. la Bioética y los Derechos Humanos Como Herramientas para Alcanzar la Plena Dignidad en la Diversidad Funcional; Diversitas-AIES: Vedra, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Romañach, J.; Lobato, M. Diversidad Funcional, Nuevo Término para la Lucha por la Dignidad en la Diversidad del ser Humano; Foro de Vida Independiente: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; OHCHR; UN Women; UNAIDS; UNDP; UNFPA; UNICEF. Eliminating Forced, Coercive and Otherwise Involuntary Sterilization: An Interagency Statement; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, E. El Reflejo de la Mujer en el Espejo de la Discapacidad: La Conquista de los Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos de las Mujeres con Discapacidad; Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J.; Luna, A. Intersecciones de género y discapacidad. La inclusión laboral de mujeres con discapacidad. Soc. Econ. 2018, 35, 158–177. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Riío-Ferres, E.; Megiías, J.L.; Expoísito, F. Gender-based violence against women with visual and physical disabilities. Psicothema 2013, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo Alonso, M.A.; Alcedo, M.A.; Bermejo, B.; Aguado, A.L. El abuso sexual en personas con discapacidad intellectual. Psicothema 2002, 14, 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez, A. El Derecho a Ser Madre. In Maternidad y Discapacidad. Colección Barclays Igualdad y Diversidad; Peláez, A., Ed.; Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación CERMI Mujeres. Protocolo para la Atención a Mujeres con Discapacidad Víctimas de Violencia; Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, J.; Hughes, R.B.; Nosek, M.A.; Groff, J.Y.; Swedlend, N.; Dolen Mullen, P. Abuse Assessment Screen—Disability (AAS-D): Measuring frequency, type, and perpetrator of abuse toward women with physical disabilities. J. Women’s Health Gend.-Based Med. 2001, 10, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.; Padilla, V.; Gutiérrez, A. Mujeres Maltratadas por su Pareja. Guía de Tratamiento Psicológico; Minerva Ediciones: Lima, Peru, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Igualdad. Macroencuesta de Violencia Contra la Mujer 2019; Ministerio de Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty, C.; Brown, J. Screening for abuse in Spanish-speaking women. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2002, 15, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Integración Social y Salud; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- Wetherell, M.; Potter, J. El análisis del discurso y la identificación de los repertorios interpretativos. In Psicologías, Discursos y Poder; Gordo, A., López, J., Eds.; Visor: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M.; Lachica, E.; Molina, A.; Villanueva de la Torre, H. Violencia contra la mujer. El perfil del agresor: Criterios de valoración del riesgo. Cuad. Med. Forense 2004, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, L. Perfil sociodemográfico y delictivo en maltratadores encarcelados en Gran Canaria por Violencia de Género en el entorno familiar. Rev. Clepsydra 2020, 19, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Estatal de la Discapacidad (Ed.) Informe Olivenza 2020–2021; Observatorio Estatal de la Discapacidad: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mailhot Amborski, A.; Bussieres, E.L.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Joyal, C.C. Sexual violence against persons with disabilities: A meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 1330–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Huete, A. Estudio Sobre el Agravio Comparativo Económico Que Origina la Discapacidad; Ministerio de Sanidad Política Social e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.R.; Lund, E.M. Socioeconomic status and geographical rural settings’ contribution to oppression of women with disabilities who experience gender violence. In Religion, Disability, and Interpersonal Violence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Yang, L. ‘Me too!’: Individual empowerment of disabled women in the# MeToo movement in China. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 842–847. [Google Scholar]

- Donoso-Vaízquez, T.; Luna-Gonzaílez, E.; Velasco-Martiínez, A. Relación entre autoestima y violencia de género. Un estudio con mujeres autóctonas y migradas en territorio español. Trabajo Social Global—Global Social Work. Rev. Investig. Interv. Soc. 2017, 7, 93–119. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Organization Acronym | Organization Name | Profile of the Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | ONCE | Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles | For the autonomy and inclusion of blind people and people with visual disability |

| P2 | CERMI | Comité Español de Representantes de Personas con Discapacidad | Platform for the representation, defense, and action of Spanish citizens with disabilities |

| P3 | ACIME | Asociación Militares y Guardias Civiles con Discapacidad | Defense of the rights of soldiers and civil guards who have acquired a sudden disability |

| P4 | FAMDIF | Federación de Asociaciones Murcianas de Personas con Discapacidad Física y Orgánica | Social and cultural inclusion of people with physical and organic disabilities for normalized active participation in society |

| P5 | PI | Plena Inclusión | For the development of the quality-of-life project for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities and their families |

| P6 | FUNDOWN | Fundación Síndrome de Down Región de Murcia | For the care and promotion of Personal Autonomy of the group of people with intellectual disabilities and/or Down Syndrome |

| P7 | FUNDOWN |

| SECTION 1: Perception of Well-Being and Resilience | ||

|---|---|---|

| Categories | Subcategories | |

| General life assessment | ||

| Life satisfaction | ||

| Life purposes | ||

| Self-esteem | ||

| Relational | ||

| Support network | ||

| Sense of belonging and inclusion | ||

| Threats/resilience/emotional | ||

| Fear, insecurities | ||

| Resilience/response strategies | ||

| Professional emotional support | ||

| General emotional state | ||

| SECTION 2: Perception of control and decision making | ||

| Relationships and friendship | ||

| Current situation | ||

| Motivations | ||

| Limitations | ||

| Romantic | ||

| Relationships | ||

| Sexual relationships | ||

| Motivations | ||

| Limitations | ||

| Health/reproductive | ||

| Health decisions and self-determination | ||

| Access to healthcare | ||

| Pregnancy and motherhood | ||

| Work/economic | ||

| Skills and motivations | ||

| Access to belongings | ||

| Economic independence | ||

| Financial management | ||

| Independence/Control/Self-determination | ||

| Independence | ||

| Control | ||

| Self-determination | ||

| SECTION 3: Gender-based and/or intimate partner violence (sexual, physical, and psychological) and violence in close surroundings | ||

| Home/close surroundings (non-partner) | ||

| Experience of violence | ||

| Narrative/discourse of the experience | ||

| Partner | ||

| Experience of violence | ||

| Narrative/discourse of the experience | ||

| Sexual | ||

| Sexual assault and harassment | ||

| Narrative of the experience | ||

| Characteristics of abuse | ||

| Characteristics | ||

| Frequency and temporality | ||

| Perpetrator | ||

| Relationship (past and present) | ||

| Addictions | ||

| Psychological profile (controlling, possessive, and abusive) | ||

| Victimhood 1 | ||

| Experience | ||

| Justification | ||

| Support | ||

| Victimhood 2 | ||

| Institutional response | ||

| CODE INT | C. Letter | CODE QUE | Age | Diagnoses | DIAG CODE | City |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 87 | 32 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Molina de Segura |

| 2 | M | 102 | 74 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Cehegín |

| 3 | S | 23 | 25 | Intellectual Disability | DI | Cartagena |

| 4 | M | 16 | 29 | Intellectual Disability | DI | Cartagena |

| 5 | M | 157 | 48 | Multiple Diagnoses | Mu | Las Torres de Cotillas |

| 7 | Y | 5 | 34 | Intellectual Disability | DI | Murcia |

| 8 | N | 88 | 53 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Molina de Segura |

| 9 | M | 85 | 39 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Molina de Segura |

| 10 | C | 105 | 66 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Mula |

| 11 | T | 11 | 37 | Mobility Problems | PM | Murcia |

| 12 | M | 12 | 55 | Physical Disability | DF | Murcia |

| 13 | M | 154 | 47 | Organic Disability | DO | Alguazas |

| 14 | P | 54 | 49 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Cieza |

| 15 | M | 52 | 37 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | Cieza |

| 16 | E | 44 | 37 | Psychosocial Disability | DPsi | San Javier |

| 19 | Y | 36 | 57 | Mobility Problems | PM | San Pedro del Pinatar |

| 22 | Y | 74 | 21 | Multiple Diagnoses | Mu | Los Alcázares |

| 23 | E | 76 | 29 | Intellectual Disability | DI | San Javier |

| Variable | N (% Valid) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Current age (n = 158) | Mean (SD): 44.21 (13.35) |

| Median: 45.00 | |

| Minimum: 21 | |

| Maximum: 88 | |

| From 21 to 30 years | 27 (17.1) |

| From 31 to 40 years | 40 (25.3) |

| From 41 to 50 years | 35 (22.2) |

| From 51 to 60 years | 36 (22.8) |

| 61 years and above | 17 (10.8) |

| Place of residence | |

| Alone | 22 (13.9) |

| Family members | 116 (73.4) |

| Shared apartments | 3 (1.9) |

| Residential facilities | 7 (4.4) |

| Other options | 10 (6.3) |

| Recognized degree of disability | |

| Recognized degree of disability (n = 158) | Median (SD): 65% (SD: 16.16) |

| 33 to 64% | 59 (37.3) |

| 65 to 75% | 53 (33.5) |

| Over 75% | 19 (12.0) |

| Educational level | |

| Higher education | 28 (17.7) |

| Non-higher education | 127 (80.4) |

| Recognized disability | |

| Intellectual | 91 (57.6) |

| Non-intellectual | 67 (42.4) |

| Membership in the associative movement | |

| No | 60 (38.0) |

| Unsure | 17 (10.8) |

| Yes | 81 (51.2) |

| Working status | |

| Employed | 51 (32.3) |

| Unemployed | 107 (67.7) |

| Financial assistance | |

| No | 60 (38.0) |

| Unsure | 21 (13.3) |

| Yes, myself | 52 (32.9) |

| Yes, others | 25 (15.8) |

| Variables | No | Yes | Chi | Df | sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Educational level | |||||||

| Higher education Non-higher education | 21 69 | 75 54.8 | 7 57 | 25 45.2 | 3.863 | 1 | 0.049 * |

| Financial assistance | |||||||

| No Unsure Yes, myself Yes, others | 40 16 24 12 | 66.7 76.2 47.1 48.0 | 20 5 27 13 | 33.3 23.8 52.9 52 | 8.246 | 3 | 0.046 * |

| Variables | No | Yes | Chi | Df | sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Educational level | |||||||

| Higher education Non-higher education | 24 83 | 85.7 65.9 | 4 43 | 14.3 34.1 | 4.253 | 1 | 0.039 * |

| Membership in the associative movement | |||||||

| No Unsure Yes | 34 13 62 | 57.6 76.5 76.5 | 25 4 19 | 42.4 23.5 23.5 | 6.200 | 2 | 0.045 * |

| Working status | |||||||

| Employed Unemployed | 41 68 | 80.4 64.2 | 10 38 | 19.6 35.8 | 4.279 | 1 | 0.039 * |

| Variables | No | Yes | Chi | Df | sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Working status | |||||||

| Employed Unemployed | 49 89 | 96.1 84.0 | 2 17 | 3.9 16.0 | 4.752 | 1 | 0.029 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zamora Arenas, J.; Millán Jiménez, A.; Bote, M. Health and Socioeconomic Determinants of Abuse among Women with Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126191

Zamora Arenas J, Millán Jiménez A, Bote M. Health and Socioeconomic Determinants of Abuse among Women with Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126191

Chicago/Turabian StyleZamora Arenas, Javier, Ana Millán Jiménez, and Marcos Bote. 2023. "Health and Socioeconomic Determinants of Abuse among Women with Disabilities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126191

APA StyleZamora Arenas, J., Millán Jiménez, A., & Bote, M. (2023). Health and Socioeconomic Determinants of Abuse among Women with Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126191