The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning

Abstract

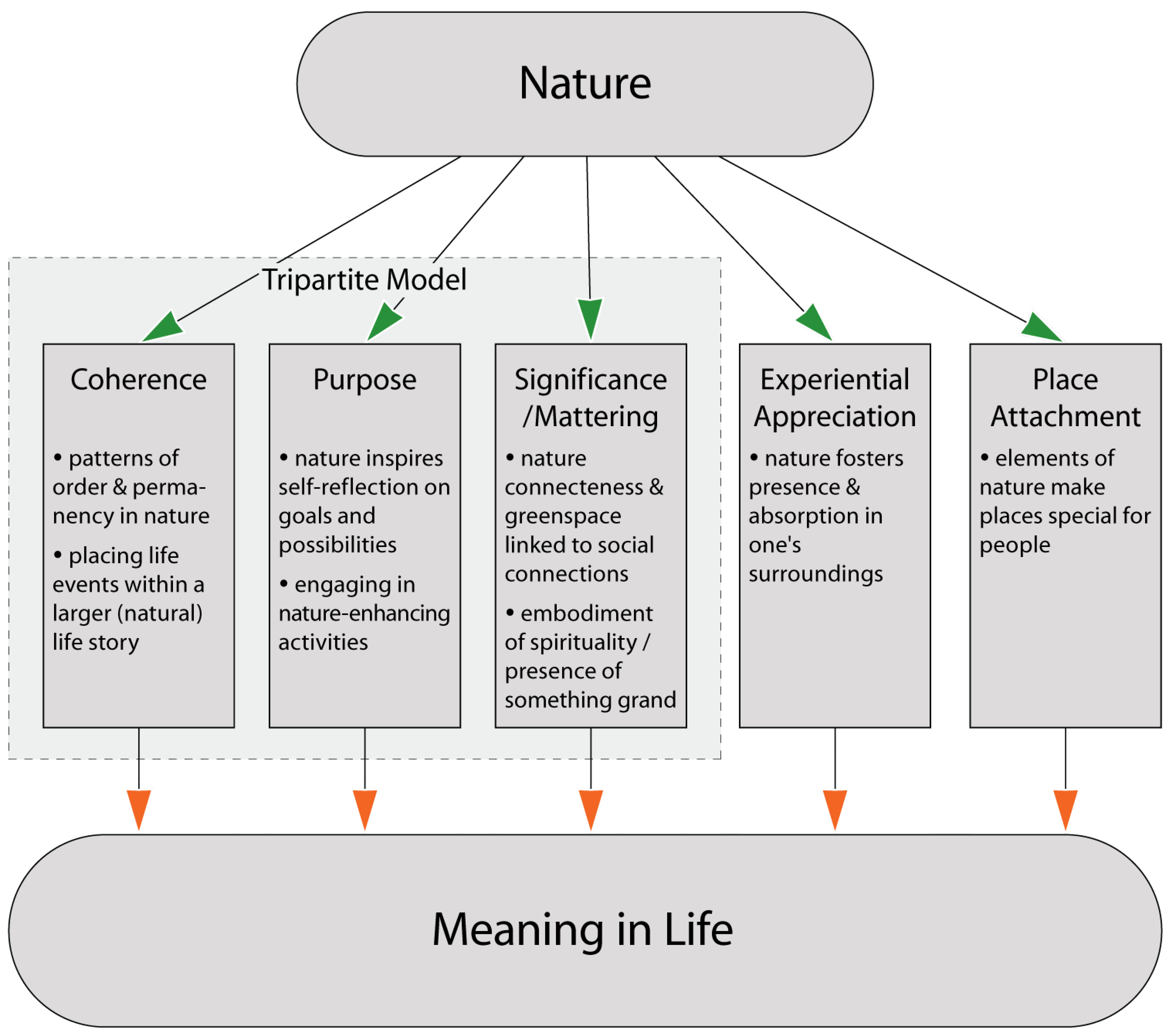

1. Introduction

“Those who come to the natural world for meaning will not go away unrewarded”—([1], p. 7).

2. Providing Meaning

2.1. Nature and Meaning in Life: In General

2.2. Nature Pathways to Meaning in Life: Coherence

2.3. Nature Pathways to Meaning in Life: Significance/Mattering

2.3.1. Social Significance/Mattering

2.3.2. Cosmic Significance/Mattering and Spirituality

2.4. Nature Pathways to Meaning in Life: Purpose

2.5. Nature Pathways to Meaning in Life: Experiential Appreciation

2.6. Nature Pathways to Meaning in Life: A Place of Attachment

3. Making Meaning

4. Threats to Nature—Threats to Meaning

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritland, R.M. A Search for Meaning in Nature: A New Look at Creation and Evolution; Pacific Press: Nampa, ID, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V. Man’s Search for Meaning; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Note, N. Why it definitely matters how we encounter nature. Environ. Ethics 2009, 31, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybron, D.M. Central Park: Nature, context, and human wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2011, 1, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Annas, J. Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Holder, M.D. Foundational frameworks of positive psychology: Mapping well-being orientations. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2015, 56, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and meaning: Me versus us; fleeting versus enduring. In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being; Vittersø, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Passmore, H.-A.; Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Dopko, R.L. Flourishing in nature: A review of the well-being benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a positive psychology intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D. The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 608–618. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F. A Wonderful Life: Insights on Findings a Meaningful Existence; HarperCollins: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- George, L.S.; Park, C.L. Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016, 20, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.S.; Park, C.L. The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Steger, M.F. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing between coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Steger, M.F. The role of significance relative to the other dimensions of meaning in life—An examination utilizing the three dimensional meaning in life scale (3DM). J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 18, 606–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Holte, P.; Martela, F.; Shanahan, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Eisenbeck, N.; Carreno, D.F.; Schlegel, R.J.; Hicks, J.A. Experiential appreciation as a pathway to meaning in life. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Chamberlain, K. Dimensions of life meaning: A qualitative investigation at mid-life. Br. J. Psychol. 1993, 87, 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Reker, G.T. Manual of the Sources of Meaning ProfileRevised (SOMP-R); Student Psychologists Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T. The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegg, M.J.; Kramer, M.; L’hoste, S.; Borasio, G.D. The Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (SMiLE): Validation of a new instrument for meaning-in-life research. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 35, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reker, G.T.; Woo, L.C. Personal meaning orientations and psychosocial adaptation in older adults. SAGE Open 2011, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernes, J.L.; Kinnier, R.T. Meaning in psychologists’ personal and professional lives. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2008, 48, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshtari, L.T.; Monadi, M.; Ashkezari, M.K.; Khamesan, A. Identifying students’ meaning in life: A phenomenological study. Biannu. J. Appl. Couns. 2016, 6, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Shim, Y.; Rush, B.R.; Brueske, L.A.; Shin, J.Y.; Merriman, L.A. The mind’s eye: A photographic method for understanding meaning in people’s lives. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. What Makes Life Meaningful? Views from 17 Advanced Economies. [Report]. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/11/18/what-makes-life-meaningful-views-from-17-advanced-economies/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Hamann, G.A.; Ivtzan, I. 30 minutes in nature a day can increase mood, well-being, meaning in life and mindfulness: Effects of a pilot programme. Soc. Inq. Into Well-Being 2016, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Howell, A.J. Nature involvement increases hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: A two-week experimental study. Ecopsychology 2014, 6, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Yang, Y.; Sabine, S. An extended replication study of the well-being intervention, the Noticing Nature Intervention (NNI). J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2663–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Han, R.; Chen, S.X. Why does nature enhance psychological well-being? A Self-Determination account. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. The quest to mental well-being: Nature connectedness, materialism and the mediating role of meaning in life in the Philippine context. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervinka, R.; Röderer, K.; Hefler, E. Are nature lovers happy? On various indicators of well-being and connectedness with nature. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Nisbet, E.K. Happiness and feeling connected: The distinct role of nature relatedness. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaulana, S.; Kahili-Heede, M.; Riley, L.; Park, M.L.N.; Makua, K.L.; Vegas, J.K.; Antonio, M.C.K. A scoping review of nature, land, and environmental connectedness and relatedness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.-A.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship. Int. J. Wellbeing 2021, 11, 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, S.J.; Proulx, T.; Vohs, K.D. The Meaning Maintenance Model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintzelman, S.J.; King, L.A. On knowing more than we can tell: Intuitive processes and the experience of meaning. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Meanings of Life; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. What is existential positive psychology? Int. J. Existent. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Reker, G.T.; Wong, P.T.P. Aging as an individual process: Toward a theory of personal meaning. In Emergent Theories of Aging; Birren, J.E., Bengtson, V.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 214–246. [Google Scholar]

- Reker, G.T.; Wong, P.T.P. Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. Patterns in Nature: Why the Natural World Looks the Way It Does; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, A. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- McKibben, B. The End of Nature; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon, M. Wellbeing; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Existential Positive Psychology: Experiences in nature, existential anxieties, and well-being. Humanist. Psychol. 2014, 42, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, S. ChangeAbility: How Artists, Activists, and Awakeners Navigate Change; Archer: Alachua County, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R.; McLeod, J. Incorporating nature into therapy: A framework for practice. J. Syst. Ther. 2006, 25, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G.W. Nature-Guided Therapy: Brief Integrative Strategies for Health and Wellbeing; Brunner/Mazel: Levittown, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lipowski, M.; Krokosz, D.; Łada, A.; Sližik, M.; Pasek, M. Sense of coherence and connectedness to nature as predictors of motivation for practicing karate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.M.; Stillman, T.F.; Hicks, J.A.; Kamble, S.; Baumeister, R.F.; Fincham, F.D. To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, V.; Vignoles, V.L. Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 864–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.; Fiske, A.P.; Schubert, T.W. The role of social relational emotions for human-nature connectedness. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Dopko, R.L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, R.R.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nghiem, L.T.P.; Chang, C.; Tan, C.L.Y.; Quazi, S.A.; Shanahan, D.F.; Lin, B.B.; Gaston, K.J.; Fuller, R.A.; et al. Connection to nature and time spent in gardens predicts social cohesion. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Jones, C. The relationship between connectedness to nature and well-being: A meta-analysis. Curr. Res. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2022, 3, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E. Social aspects of urban forestry: The role of aboriculture in a healthy social ecology. J. Aboricult. 2003, 29, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orban, E.; Sutcliffe, R.; Dragano, N.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Moebus, S. Residential surrounding greenness, self-rated health and interrelations with aspects of neighborhood environment and social relations. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavell, M.A.; Leiferman, J.A.; Gascon, M.; Braddick, F.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Litt, J.S. Nature-based social prescribing in urban settings to improve social connectedness and mental well-being: A review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.W.; Keltner, D. Awe and the natural environment. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Friedman, H.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Piff, P.K.; Dietze, P.; Feinberg, M.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, P.; Saroglou, V. Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2012, 4, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldy, S.P.; Piff, P.K. Toward a social ecology of prosociality: Why, when, and where nature enhances social connection. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keltner, D. Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life; Penguin Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Holder, M.D. Noticing nature: Individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Yargeau, A.; Blench, J. Wellbeing in winter: Testing the Noticing Nature Intervention during winter months. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 840273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. The Varieties of Religious Experience; Longmans, Green, and Co.: London, UK, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Bethelmy, L.C.; Corraliza, J.A. Transcendence and sublime experience in nature: Awe and inspiring energy. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. The transpersonal dimensions of ecopsychology: Nature, nonduality, and spiritual practice. Humanist. Psychol. 1998, 26, 69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinzing, M.; Van Cappellen, P.; Fredrickson, B.L. More than a momentary blip in the universe? Investigating the link between religiousness and perceived meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2023, 49, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsis, I.; Francis, A.J.P. Spirituality mediates the relationship between engagement with nature and psychological wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Tipsord, J.M.; Tate, E.M. Allo-inclusive identity: Incorporating the social and natural worlds into one’s sense of self. In Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Exploration of the Quiet Ego; Wayment, H.A., Bauer, J.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Trigwell, J.L.; Francis, A.J.P.; Bagot, K.L. Nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: Spirituality as a potential mediator. Ecopsychology 2014, 6, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, P. Toward an understanding and definition of wilderness spirituality. Aust. Geogr. 2007, 38, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, P. The wilderness experience and spirituality: What recent research tells us. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2003, 74, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, L.; Mayseless, O. The therapeutic value of experiencing spirituality in nature. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 2020, 7, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Little, D.E. Qualitative insights into leisure as a spiritual experience. J. Leis. Res. 2007, 39, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhaar, T.L. Evolutionary advantages of intense spiritual experiences in nature. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2009, 3, 303–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnin, J. The Spirituality of Nature; Northstone Wood Lake Publishing: Kelowna, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shibley, M.A. Sacred nature: Earth-based spirituality as popular religion in the Pacific Northwest. J. Study Relig. Nat. Cult. 2011, 5, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. Earth and nature-based spirituality (Part I): From deep ecology to radical environmentalism. Religion 2001, 31, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, C. The Spirituality Scale: Development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. J. Holist. Nurs. 2005, 23, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.; Fisher, J.W. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1975–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.G.; Teresi, J.A. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.E.; Rice, K.; Hook, J.N.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; DeBlaere, C.; Choe, E.; Worthington, E.L. Development of the Sources of Spirituality Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Steger, M.F. Promoting meaning and purpose in life. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Positive Psychological Interventions; Parks, A.C., Schueller, S.M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.Y.; Steger, M.F. Supportive college environment for meaning searching and meaning in life among American college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2016, 57, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttie, J. Seven Ways to Find Purpose in Life; Greater Good Magazine, Greater Good Science Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/seven_ways_to_find_your_purpose_in_life (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Cohen, A.B.; Gruber, J.; Keltner, D. Comparing spiritual transformations and experiences of profound beauty. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2010, 2, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.R.; Seburn, M.; Averill, J.R.; More, T.A. Solitude experiences: Varieties, settings, and individual differences. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofija, E.; Cleary, A.; Sav, A.; Sebar, B.; Harris, N. How emerging adults perceive elements of nature as resources for wellbeing: A qualitative photo-elicitation study. Youth 2022, 2, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granerud, A.; Eriksson, B.G. Mental health problems, recovery, and the impact of green care services: A qualitative, participant-focused approach. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2014, 30, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debats, D.L. Sources of meaning: An investigation of significant commitments in life. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1999, 39, 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.A.; Mathews, C. Building a culture of conservation: Research findings and research priorities on connecting people to nature in parks. Parks 2015, 21, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Omoto, A.M. Absorption: How nature experiences promote awe and other positive emotions. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Conner, T.S. The quality of time in nature: How fascination explains and enhances the relationship between nature experiences and daily affect. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, Y.; van den Berg, A. Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, D. Do meaningful relationships with nature contribute to a worthwhile life? Environ. Values 2008, 17, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M. Nature Connection: A Fast, Slow and Portable Sense of Place; Finding Nature, 2017. Available online: https://findingnature.org.uk/2017/10/12/nature-connection-a-fast-slow-and-portable-sense-of-place/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Wolf, K.L.; Krueger, S.; Flora, K. Place Attachment and Meaning—A Literature Review. Place Attachment and Meaning. 2014. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/hhwb/Thm_Place.html (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Bush, J.; Hernandez-Santin, C.; Hes, D. Nature in place: Placemaking in the biosphere. In Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment; Hes, D., Hernandez-Santin, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, A. The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Trust UK. Why Places Matter to People: Research Report. 2017. Available online: https://nt.global.ssl.fastly.net/binaries/content/assets/website/national/pdf/why-places-matter-to-people.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.N.; Baldwin, M.; Westgate, E. Does Place Attachment Foster Meaning in Life in Everyday Life? [Poster Presentation]; Society for Personality and Social Psychology Annual Convention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, A.N.; Baldwin, M.; Westgate, E. Experimental Evidence for the Link between Places of Attachment and Meaning in Life; [Poster Presentation]; Society for Personality and Social Psychology Annual Convention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Dasgupta, R. The mediating role of place attachment between nature connectedness and human well-being: Perspectives from Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.; Barbett, L.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro-nature conservation behaviours. People Nat. 2020, 2, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M.; Steger, M.F. Meaningfulness as satisfaction of autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: Comparing the four satisfactions and positive affect as predictors of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, T. Individual differences in meaning-making: Considering the variety of sources of meaning, their density and diversity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, S.J.; Steg, L.; Bouman, T. Meta-analytic evidence for a robust and positive association between individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors and their subjective wellbeing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Haggar, P.; Brügger, A. The connection between subjective wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour: Individual and cross-national characteristics in a seven-country study. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 133, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhoeven, L.A.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Why going green feels good. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinario, E.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Bonaiuto, F.; Bonnes, M.; Cicero, L.; Fornara, F.; Scopelliti, M.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; et al. Motivations to act for the protection of nature biodiversity and the environment: A matter of “significance”. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1133–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Uren, H.; Hardcastle, S.J.; Ryan, R.M. Community gardening: Basic psychological needs as mechanisms to enhance individual and community well-being. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Born, R.J.G.; Arts, B.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Knights, P.; Molinario, E.; Horvat, K.P.; Porras-Gomez, C.; Smrekar, A.; Soethe, N.; et al. The missing pillar: Eudemonic values in the justification of nature conservation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/ (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Trisos, C.H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A.L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budziszewska, M.; Jonsson, S.E. From climate anxiety to climate action: An existential perspective on climate change concerns within psychotherapy. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 002216782199324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Barnwell, G.; Johnstone, L.; Shukla, K.; Mitchell, A. The Power Threat Meaning Framework and the climate and ecological crises. Psychol. Soc. 2022, 63, 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. The process of eco-anxiety and ecological grief: A narrative review and a new proposal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Lutz, P.K.; Howell, A.J. Eco-anxiety: A cascade of fundamental existential anxieties. J. Constr. Psychol. 2023, 36, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinzing, M.M.; Sappenfield, C.A.; Fredrickson, B.L. What makes me matter? Investigating how and why people feel significant. J. Posit. Psychol. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumber, R.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Passmore, H.-A.; Howell, A.J.; Zelenski, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Richardson, M. The continuum of eco-anxiety responses: A preliminary investigation of its nomological network. Collabra Psychol. 2023, 9, 67838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Newman, D.B. Eco-anxiety in daily life: Relationships with well-being and pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet-Tinaoui, S.; Gousse-Lessard, A.-S.; Bolvin, M. Eco-Anxiety and Well-Being: Finding Meaning through Collective Action. [Poster Presentation]. In Proceedings of the International Positive Psychology Association 7th World Congress on Positive Psychology, Virtual Conference, 15–17 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments—Healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Gascon, M.; Perez-Leon, D.; Mudu, P. Green spaces and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e469–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy nature healthy people: ‘Contact with nature’ as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekierda, K.; Banik, A.; Park, C.L.; Luszczynska, A. Meaning in life and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Park, C.L. A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2018, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.E. A Philosophy of Gardens; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.P. Finding—And failing to find—Meaning in nature. Environ. Values 2013, 22, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Passmore, H.-A.; Krause, A.N. The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126170

Passmore H-A, Krause AN. The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126170

Chicago/Turabian StylePassmore, Holli-Anne, and Ashley N. Krause. 2023. "The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126170

APA StylePassmore, H.-A., & Krause, A. N. (2023). The Beyond-Human Natural World: Providing Meaning and Making Meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126170