Anticoagulant Treatment in Patients with AF and Very High Thromboembolic Risk in the Era before and after the Introduction of NOAC: Observation at a Polish Reference Centre

Abstract

1. Introduction

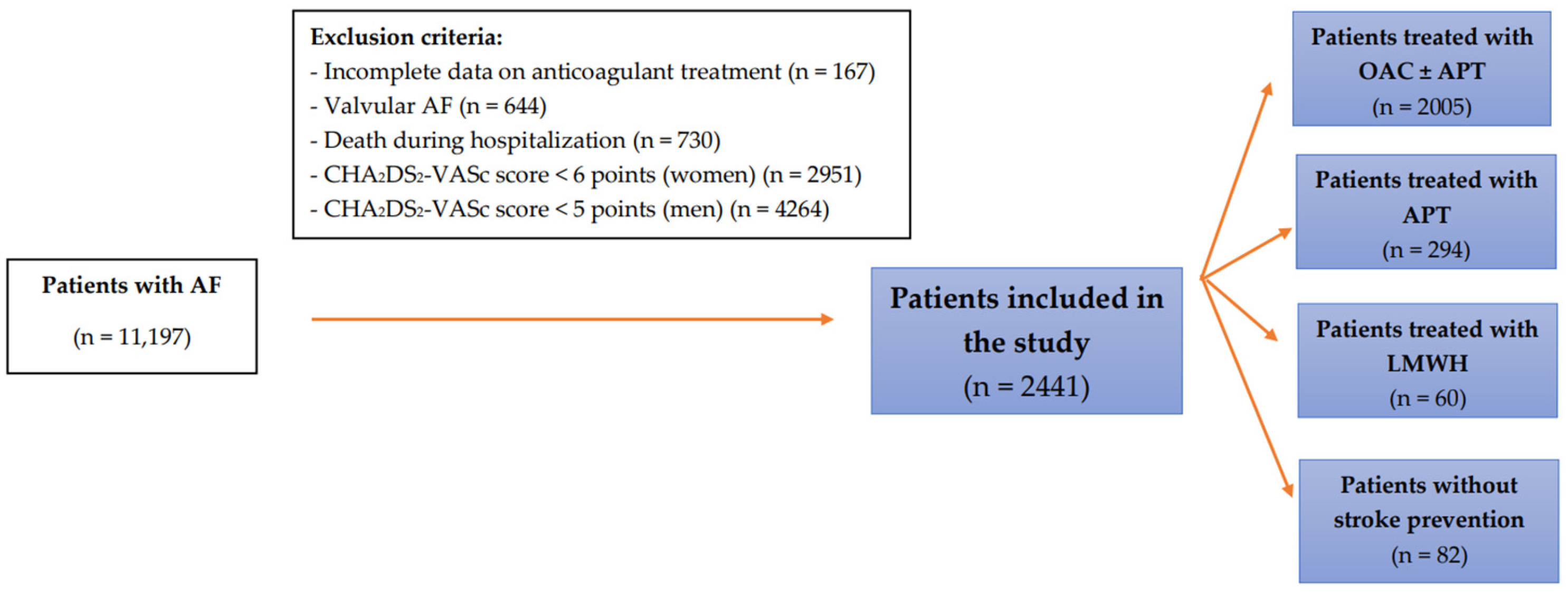

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group

2.2. Methods

2.3. Assessment of the Thromboembolic Risk

2.4. Management of Antithrombotic Therapy

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Predictors of Non-OAC Treatment in Very High-Risk Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C.J.; Toft-Petersen, A.P.; Ozenne, B.; Phelps, M.; Olesen, J.B.; Ellinor, P.T.; Gislason, G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gerds, T.A. Assessing absolute stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation using a risk factor-based approach. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 2021, 7, f3–f10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öz, A.; Cinar, T.; Güler, C.K.; Efe, S.Ç.; Emre, U.; Karabağ, T.; Ayça, B. Novel electrocardiography parameter for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in acute ischaemic stroke patients: P wave peak time. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotalczyk, A.; Mazurek, M.; Kalarus, Z.; Potpara, T.S.; Lip, G.Y.H. Stroke prevention strategies in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potpara, T.S.; Lip, G.Y. Oral anticoagulant therapy in atrial fibrillation patients at high stroke and bleeding risk. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Nieuwlaat, R.; de Vos, C.B.; Crijns, H.J.; Lip, G.Y. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010, 138, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, V.; Marin, F.; Fernandez, H.; Manzano-Fernandez, S.; Gallego, P.; Valdes, M.; Vicente, V.; Lip, G.Y.H. Predictive value of the HAS-BLED and ATRIA bleeding scores for the risk of serious bleeding in a “real-world” population with atrial fibrillation receiving anticoagulant therapy. Chest 2013, 143, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besford, M.; Leahy, T.P.; Sammon, C.; Ulvestad, M.; Carroll, R.; Mehmud, F.; Alikhan, R.; Ramagopalan, S. CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED risk scores and real-world oral anticoagulant prescribing decisions in atrial fibrillation. Future Cardiol. 2021, 17, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchhof, P.; Benussi, S.; Kotecha, D.; Ahlsson, A.; Atar, D.; Casadei, B.; Castella, M.; Diener, H.C.; Heidbuchel, H.; Hendriks, J.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2016, 50, e1–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Calkins, H.; Chen, L.Y.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C., Jr.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; Furie, K.L.; et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, T.F.; Liu, C.J.; Wang, K.L.; Lin, Y.J.; Chang, S.L.; Lo, L.W.; Hu, Y.F.; Tuan, T.C.; Chen, T.J.; Lip, G.Y.; et al. Should atrial fibrillation patients with 1 additional risk factor of the CHA2DS2-VASc score (beyond sex) receive oral anticoagulation? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J.B.; Lip, G.Y.; Hansen, M.L.; Hansen, P.R.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Lindhardsen, J.; Selmer, C.; Ahlehoff, O.; Olsen, A.M.; Gislason, G.H.; et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, d124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friberg, L.; Hammar, N.; Ringh, M.; Pettersson, H.; Rosenqvist, M. Stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation: Who gets it and who does not? Report from the Stockholm Cohort-study on Atrial Fibrillation (SCAF-study). Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 1954–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, I.M.; Newton, N.; Welner, S.A.; Cowell, W.; Lip, G.Y. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 638–645 e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo Garcia, J.; Vargas Ortega, D.; Formiga, F.; Unzueta, I.; Fernandez de Cabo, S.; Chaves, J. Profiling of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate-to-high risk of stroke not receiving oral anticoagulation in Spain. Semergen 2019, 45, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, T.F.; Chiang, C.E.; Chan, Y.H.; Liao, J.N.; Chen, T.J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Chen, S.A. Oral anticoagulants in extremely-high-risk, very elderly (>90 years) patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2021, 18, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gažová, A.; Leddy, J.J.; Rexová, M.; Hlivák, P.; Hatala, R.; Kyselovič, J. Predictive value of CHA2DS2-VASc scores regarding the risk of stroke and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (CONSORT compliant). Medicine 2019, 98, e16560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C.; Conti, J.B.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014, 130, 2071–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhof, P.; Benussi, S.; Kotecha, D.; Ahlsson, A.; Atar, D.; Casadei, B.; Castella, M.; Diener, H.C.; Heidbuchel, H.; Hendriks, J.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2893–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Crijns, H.J. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010, 137, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpotowicz, A.; Gorczyca-Głowacka, I.; Uziębło-Życzkowska, B.; Maciorowska, M.; Wójcik, M.; Błaszczyk, R.; Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; Gawałko, M.; Budnik, M.; Tokarek, T.; et al. Czy wynik CHA2DS2-VASc determinuje leczenie przeciwzakrzepowe u pacjentów z migotaniem przedsionków? Dane z POLish Atrial Fibrillation (POL-AF) Registry? Folia Cardiol. 2021, 16, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-Y.; Lip, G.Y.; Chen, S.-A.; Chao, T.-F. Importance of risk reassessment in patients with atrial fibrillation in guidelines: Assessing risk as a dynamic process. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, M.B.; Hlavacek, P.; Keshishian, A.; Guo, J.D.; Mallampati, R.; Ferri, M.; Russ, C.; Emir, B.; Cato, M.; Yuce, H.; et al. Oral anticoagulant underutilization among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from the United States Medicare database. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2022, 66, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; He, M.; Gabriel, N.; Magnani, J.W.; KIMMEL, S.E.; Gellad, W.; Hernandez, I. Abstract MP07: Are Gaps in Anticoagulation Due to Under-prescribing Or Prescriptions Not Being Filled: An Administrative Health Claims Analysis. Circulation 2022, 145, AMP07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgman, A.S.; Nair, G.; Lyubarova, R.; Merchant, F.M.; Mason, P.; Curtis, A.B.; Wenger, N.K.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Benjamin, E.J. Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients 75 Years and Older: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelig, J.; Pisters, R.; Hemels, M.E.; Huisman, M.V.; Ten Cate, H.; Alings, M. When to withhold oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation—An overview of frequent clinical discussion topics. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y. Stroke prevention in Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Endt, V.H.W.; Milders, J.; Penning de Vries, B.B.L.; Trines, S.A.; Groenwold, R.H.H.; Dekkers, O.M.; Trevisan, M.; Carrero, J.J.; van Diepen, M.; Dekker, F.W.; et al. Comprehensive comparison of stroke risk score performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis among 6 267 728 patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2022, 24, 1739–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. Wytyczne ESC 2020 dotyczące diagnostyki i leczenia migotania przedsionków opracowane we współpracy z European Associationof Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Pol. Heart J. 2021, 79, 8–144. [Google Scholar]

- Proietti, M.; Romanazzi, I.; Romiti, G.F.; Farcomeni, A.; Lip, G.Y.H. Real-World Use of Apixaban for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation. Stroke 2018, 49, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Lane, D.A.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Lip, G.Y. Net clinical benefit of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus no treatment in a ‘real world’ atrial fibrillation population: A modelling analysis based on a nationwide cohort study. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 107, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.-E.; Naditch-Brûlé, L.; Murin, J.; Goethals, M.; Inoue, H.; O’Neill, J.; Silva-Cardoso, J.; Zharinov, O.; Gamra, H.; Alam, S. Distribution and risk profile of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation in routine clinical practice: Insight from the real-life global survey evaluating patients with atrial fibrillation international registry. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Du, X.; Wang, W.; Tang, R.B.; Luo, J.G.; Li, C.; Chang, S.S.; Liu, X.H.; Sang, C.H.; Yu, R.H.; et al. Long-Term Persistence of Newly Initiated Warfarin Therapy in Chinese Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkhon, P.; Alwafi, H.; Fanning, L.; Lau, W.C.Y.; Wei, L.; Kongkaew, C.; Wong, I.C.K. Patterns and factors influencing oral anticoagulant prescription in people with atrial fibrillation and dementia: Results from UK primary care. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubitz, S.A.; Khurshid, S.; Weng, L.-C.; Doros, G.; Keach, J.W.; Gao, Q.; Gehi, A.K.; Hsu, J.C.; Reynolds, M.R.; Turakhia, M.P.; et al. Predictors of oral anticoagulant non-prescription in patients with atrial fibrillation and elevated stroke risk. Am. Heart J. 2018, 200, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Patients n = 2441 | OAC n = 2005 | Non-OAC n = 436 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 1270 (52) | 1043 (52) | 227 (52.1) | 0.987 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 78.7 (7.2) | 78.6 (7.2) | 79.6 (6.9) | 0.007 |

| Age < 65, n (%) | 71 (2.9) | 58 (2.9) | 13 (3) | 0.920 |

| Age 65–74, n (%) | (19) | 408 (20.3) | 56 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Age > 74, n (%) | 1906 (78.1) | 1539 (76.8) | 367 (84.2) | 0.001 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2098 (85.9) 464 | 1705 (85) | 393 (90.1) | 0.005 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 2259 (92.5) | 1861 (92.8) | 398 (91.3) | 0.269 |

| Vascular disease, n (%) | 1697 (69.5) | 1417 (70.7) | 280 (64.2) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1288 (52.8) | 1057 (52.7) | 231 (53) | 0.920 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 773 (31.7) | 635 (31.7) | 138 (31.7) | 0.994 |

| Previous TIA, n (%) | 144 (5.9) | 126 (6.3) | 18 (4.1) | 0.083 |

| Peripheral thromboembolic events, n (%) | 105 (4.3) | 93 (4.6) | 12 (2.8) | 0.079 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 853 (35.2) | 718 (35.8) | 135 (31) | 0.054 |

| Stable CAD, n (%) | 841 (34.5) | 714 (35.6) | 127 (29.1) | 0.010 |

| PCI, n (%) | 530 (21.7) | 464 (23.1) | 66 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| CABG, n (%) | 238 (9.8) | 216 (10.8) | 22 (5) | <0.001 |

| PAD, n (%) | 321 (13.2) | 287 (14.3) | 34 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 96 (3.9) | 73 (3.6) | 23 (5.3) | 0.112 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, n (%) | 83 (3.4) | 62 (3.1) | 21 (4.8) | 0.072 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 121 (5) | 85 (4.2) | 36 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Thrombocythemia, n (%) | 435 (17.8) | 347 (17.3) | 88 (20.2) | 0.155 |

| Anaemia, n (%) | 647 (26.5) | 521 (26) | 126 (28.9) | 0.212 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 6 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.292 * |

| Type of AF, n (%) | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 982 (40.2) | 767 (38.2) | 215 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| Persistent | 135 (5.6) | 126 (6.3) | 9 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Permanent | 1324 (54.2) | 1112 (55.5) | 212 (48.6) | 0.009 |

| Non-permanent (paroxysmal + persistent) | 1117 (45.8) | 893 (44.5) | 224 (51.4) | 0.009 |

| Thromboembolic risk | ||||

| CHADS2, mean (SD) | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.9) | 0.361 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc, mean (SD) | 6.1 (1) | 6.1 (1) | 6.1 (1) | 0.906 |

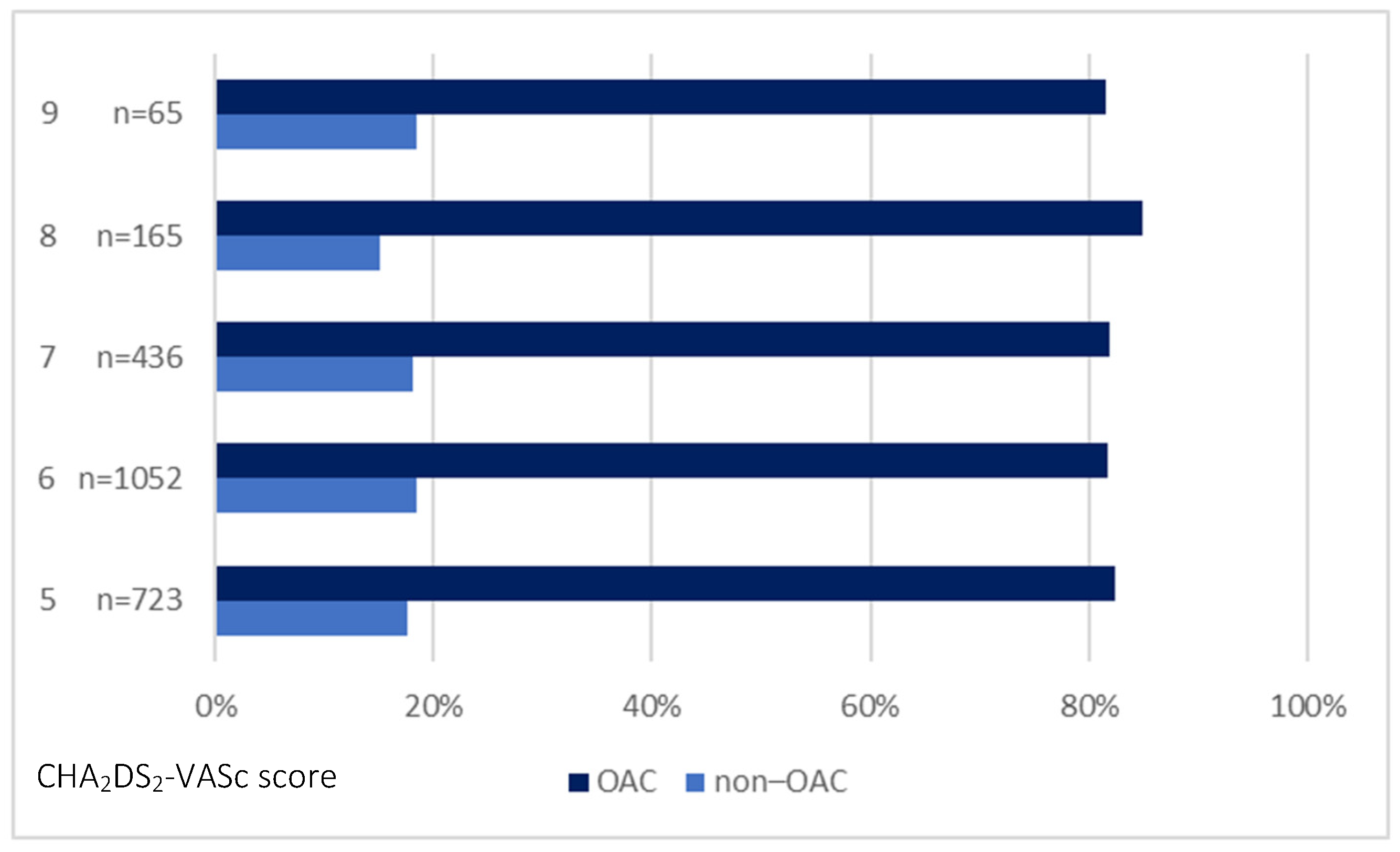

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 5, n (%) | 723 (29.6) | 596 (29.7) | 127 (29.1) | 0.804 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 6, n (%) | 1052 (43.1) | 859 (42.8) | 193 (44.3) | 0.587 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 7, n (%) | 436 (17.9) | 357 (17.8) | 79 (18.1) | 0.877 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 8, n (%) | 165 (6.8) | 140 (7) | 25 (5.7) | 0.347 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 9, n (%) | 65 (2.7) | 53 (2.6) | 12 (2.8) | 0.898 |

| Bleeding risk | ||||

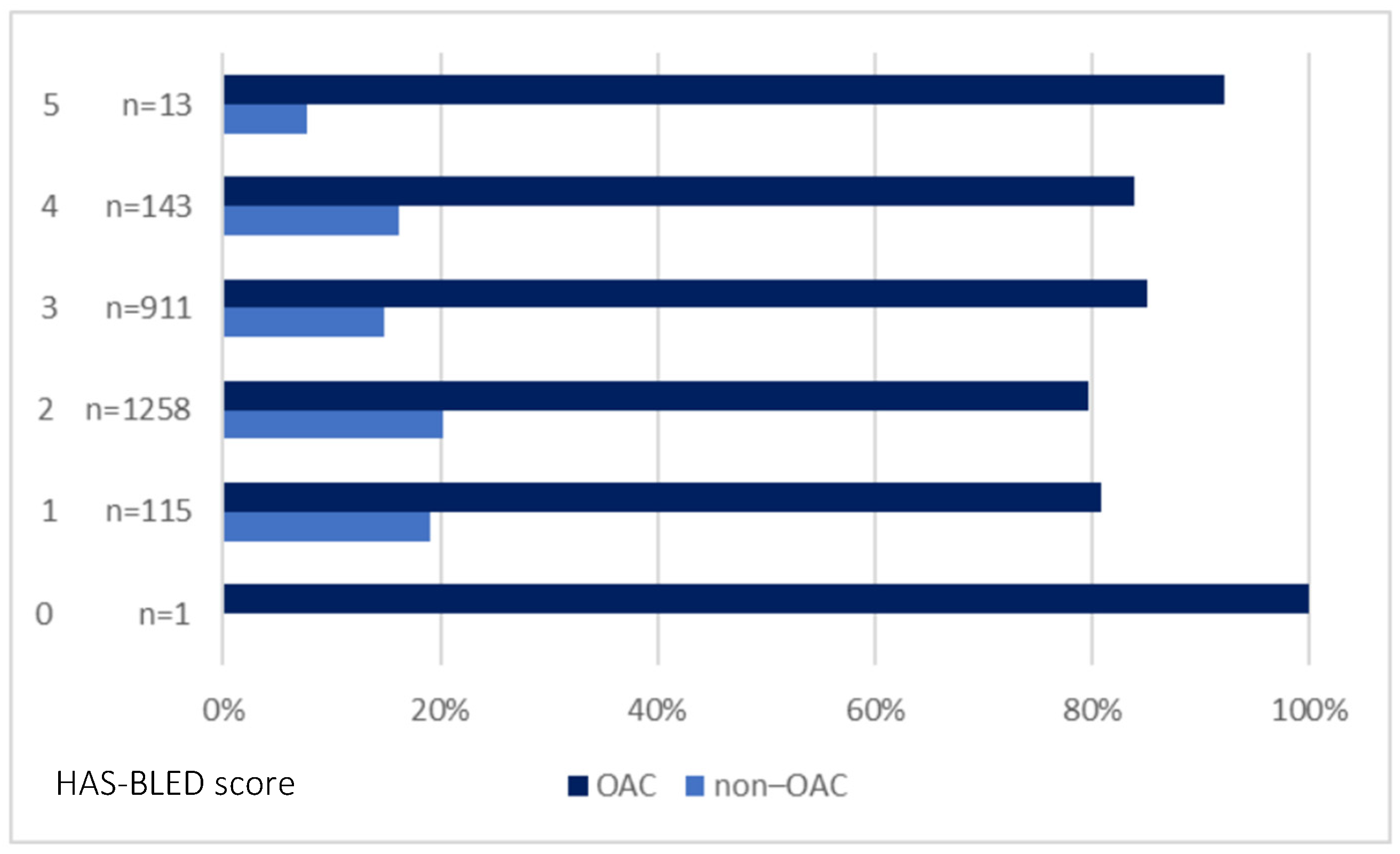

| HAS-BLED, mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.7) | 0.002 |

| HAS-BLED ≥ 3, n (%) | 1067 (43.7) | 908 (45.3) | 159 (36.5) | 0.001 |

| HAS-BLED ≥ 5, n (%) | 13 (0.5) | 12 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.485 * |

| Laboratory test results | ||||

eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2), mean (SD) | n = 2429 49.1 (15.9) | n = 1997 49.3 (15.6) | n = 432 48.7 (17.2) | 0.434 |

| eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 557 (22.9) | 459 (23) | 98 (22.7) | 0.893 |

| eGFR 59–45 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 875 (36) | 719 (36) | 156 (36.1) | 0.966 |

| eGFR 44–30 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 736 (30.3) | 614 (30.7) | 122 (28.2) | 0.304 |

| eGFR 29–15 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 237 (9.8) | 188 (9.4) | 49 (11.4) | 0.221 |

| eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 24 (1) | 17 (0.9) | 7 (1.6) | 0.174 * |

| Echocardiography | ||||

EF (%), mean (SD) | n = 1895 45.8 (12.6) | n = 1567 45.9 (12.9) | n = 328 45.2 (11.5) | 0.132 |

| EF ≥ 50%, n (%) | 920 (48.5) | 776 (49.5) | 144 (43.9) | 0.064 |

| EF 49–41%, n (%) | 305 (16.1) | 249 (15.9) | 56 (17.1) | 0.596 |

| EF ≤ 40%, n (%) | 670 (35.4) | 542 (34.6) | 128 (39) | 0.126 |

LA (mm), mean (SD) | n = 1863 47 (7.5) | n = 1541 47.3 (7.5) | n = 322 45.5 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| LA > 40 mm, n (%) | 1531 (82.2) | 1299 (84.3) | 232 (72) | <0.001 |

| LA ≤ 40 mm, n (%) | 332 (17.8) | 242 (15.7) | 90 (28) | |

| Reason for hospitalisation, n (%) | ||||

| Electrical cardioversion | 72 (2.9) | 68 (3.4) | 4 (0.9) | 0.006 |

| Planned coronary angiography/PCI or ACS | 395 (16.2) | 262 (13.1) | 133 (30.5) | <0.001 |

| Planned CIED implantation/reimplantation | 616 (25.2) | 493 (24.6) | 123 (28.2) | 0.115 |

| Heart failure | 729 (29.9) | 622 (31) | 107 (24.6) | 0.007 |

| Ablation | 19 (0.8) | 17 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0.555 * |

| Other | 457 (18.7) | 408 (20.3) | 49 (11.2) | <0.001 |

| AF without any procedures | 153 (6.3) | 135 (6.7) | 18 (4.1) | 0.042 |

| OAC 2004–2011 n = 470 | OAC 2012–2019 n = 1535 | p | Non-OAC 2004–2011 n = 281 | Non-OAC 2012–2019 n = 155 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 270 (57.4) | 773 (50.4) | 0.007 | 153 (54.4) | 74 (47.7) | 0.180 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 77.2 (6.1) | 79 (7.5) | <0.001 | 79.3 (6.3) | 80.1 (7.9) | 0.078 |

| Age < 65, n (%) | 16 (3.4) | 42 (2.7) | 0.450 | 7 (2.5) | 6 (3.9) | 0.557 * |

| Age 65–74, n (%) | 103 (21.9) | 305 (19.9) | 0.335 | 34 (12.1) | 22 (14.2) | 0.532 |

| Age > 74, n (%) | 351 (74.7) | 1188 (77.4) | 0.223 | 240 (85.4) | 127 (81.9) | 0.341 |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | ||||||

| Heart failure, n (%) | 389 (82.8) | 1316 (85.7) | 0.115 | 252 (89.7) | 141 (91) | 0.666 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 433 (92.1) | 1428 (93) | 0.508 | 256 (91.1) | 142 (91.6) | 0.857 |

| Vascular disease, n (%) | 247 (52.6) | 1170 (76.2) | <0.001 | 163 (58) | 117 (75.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 232 (49.4) | 825 (53.7) | 0.096 | 142 (50.5) | 89 (57.4) | 0.168 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 181 (38.5) | 454 (29.6) | <0.001 | 96 (34.2) | 42 (27.1) | 0.129 |

| Previous TIA, n (%) | 24 (5.1) | 102 (6.6) | 0.229 | 8 (2.8) | 10 (6.5) | 0.070 |

| Peripheral thromboembolic events, n (%) | 34 (7.2) | 59 (3.8) | 0.002 | 9 (3.2) | 3 (1.9) | 0.551 * |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 131 (27.9) | 587 (38.2) | <0.001 | 71 (25.3) | 64 (41.3) | 0.001 |

| PCI, n (%) | 70 (14.9) | 394 (25.7) | <0.001 | 32 (11.4) | 34 (21.9) | 0.003 |

| CABG, n (%) | 33 (7) | 183 (11.9) | 0.003 | 6 (2.1) | 16 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| PAD, n (%) | 14 (3) | 273 (17.8) | <0.001 | 10 (3.6) | 24 (15.5) | <0.001 |

| COPD, n (%) | 49 (10.4) | 153 (10) | 0.773 | 40 (14.2) | 16 (10.3) | 0.243 |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 8 (1.7) | 65 (4.2) | 0.010 | 10 (3.6) | 13 (8.4) | 0.031 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, n (%) | 12 (2.6) | 50 (3.3) | 0.440 | 12 (4.3) | 9 (5.8) | 0.473 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 18 (3.8) | 67 (4.4) | 0.614 | 20 (7.1) | 16 (10.3) | 0.244 |

| Thrombocythemia, n (%) | 72 (15.3) | 275 (17.9) | 0.193 | 58 (20.6) | 30 (19.4) | 0.749 |

| Anaemia, n (%) | 77 (16.4) | 444 (28.9) | <0.001 | 63 (22.4) | 63 (40.6) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0.042 * | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0.541 * |

| Type of AF, n (%) | ||||||

| Paroxysmal, n (%) | 163 (34.7) | 604 (39.4) | 0.068 | 143 (50.9) | 72 (46.4) | 0.375 |

| Persistent, n (%) | 18 (3.8) | 108 (7) | 0.012 | 3 (1.1) | 6 (3.9) | 0.076 * |

| Permanent, n (%) | 289 (61.5) | 823 (53.6) | 0.003 | 135 (48) | 77 (49.7) | 0.744 |

| Non-permanent (paroxysmal + persistent), n (%) | 181 (38.5) | 712 (46.4) | 0.003 | 146 (52) | 78 (50.3) | 0.744 |

| Thromboembolic risk | ||||||

| CHADS2, mean (SD) | 4 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.9) | 0.001 | 4 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.9) | 0.667 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc, mean (SD) | 6.1 (0.9) | 6.1 (1) | 0.792 | 6.1 (1) | 6.1 (1) | 0.371 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 5, n (%) | 128 (27.2) | 468 (30.5) | 0.177 | 83 (29.5) | 44 (28.4) | 0.800 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 6, n (%) | 224 (47.7) | 635 (41.4) | 0.016 | 129 (46) | 64 (41.3) | 0.353 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 7, n (%) | 88 (18.7) | 269 (17.5) | 0.552 | 47 (16.7) | 32 (20.6) | 0.309 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 8, n (%) | 26 (5.5) | 114 (7.4) | 0.158 | 14 (5) | 11 (7.1) | 0.363 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc = 9, n (%) | 4 (0.9) | 49 (3.2) | 0.006 | 8 (2.8) | 4 (2.6) | 1.000 |

| Bleeding risk | ||||||

| HAS-BLED, mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.7) | <0.001 | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED ≥ 3, n (%) | 173 (36.8) | 735 (47.9) | <0.001 | 78 (27.8) | 81 (52.3) | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED ≥ 5, n (%) | 0 (0) | 12 (0.8) | 0.080 * | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.356 * |

| Laboratory test results | ||||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) mean (SD) | n = 469 49.1 (15.6) | n = 1528 49.3 (15.7) | 0.931 | n = 281 49.5 (17.3) | n = 151 47.2 (16.9) | 0.155 |

| eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2, n (%) | 108 (23) | 351 (22.9) | 0.980 | 69 (24.5) | 29 (19.2) | 0.206 |

| eGFR 59–45 mL/min/1.73m2, n (%) | 163 (34.8) | 556 (36.4) | 0.519 | 106 (37.7) | 50 (33.1) | 0.342 |

| eGFR 44–30 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 146 (31.1) | 468 (30.6) | 0.837 | 71 (25.3) | 51 (33.8) | 0.061 |

| eGFR 29–15 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 48 (10.2) | 140 (9.2) | 0.487 | 32 (11.4) | 17 (11.3) | 0.968 |

| eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 4 (0.9) | 13 (0.9) | 1.000 | 3 (1.1) | 4 (2.6) | 0.245 * |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| EF (%), mean (SD) | n = 289 47.1 (13) | n = 1278 45.6 (12.8) | 0.067 | n = 194 45.1 (11.7) | n = 134 45.4 (11.3) | 0.721 |

| EF ≥ 50%, n (%) | 156 (54) | 620 (48.5) | 0.093 | 83 (42.8) | 61 (45.5) | 0.623 |

| EF 41–49%, n (%) | 39 (13.5) | 210 (16.4) | 0.217 | 34 (17.5) | 22 (16.4) | 0.793 |

| EF ≤ 40%, n (%) | 94 (32.5) | 448 (35.1) | 0.414 | 77 (39.7) | 51 (38.1) | 0.766 |

| LA (mm), mean (SD) | n = 285 46.1 (7.6) | n = 1256 47.6 (7.5) | 0.003 | n = 188 44.6 (7.1) | n = 134 46.7 (7.2) | 0.003 |

| LA > 40 mm, n (%) | 223 (78.2) | 1076 (85.7) | 0.002 | 125 (66.5) | 107 (79.9) | 0.008 |

| LA ≤ 40 mm, n (%) | 62 (21.8) | 180 (14.3) | 63 (33.5) | 27 (20.1) | ||

| Reason for hospitalisation, n (%) | ||||||

| Electrical cardioversion, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 67 (4.4) | <0.001 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.9) | 0.131 * |

| Planned coronary angiography/PCI or ACS, n (%) | 89 (19) | 173 (11.3) | <0.001 | 97 (34.5) | 36 (23.2) | 0.014 |

| Planned CIED implantation/reimplantation, n (%) | 193 (41.1) | 300 (19.5) | <0.001 | 99 (35.2) | 24 (15.5) | 0.011 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 105 (22.3) | 517 (33.7) | <0.001 | 58 (20.7) | 49 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Ablation, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 15 (1) | 0.389 * | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.126 * |

| Other, n (%) | 47 (10) | 361 (23.5) | <0.001 | 17 (6) | 32 (20.6) | <0.001 |

| AF without any procedures, n (%) | 33 (7) | 102 (6.6) | 0.776 | 9 (3.2) | 9 (5.8) | 0.191 |

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 74 | 1.78 | 1.32–2.42 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisation (in 2004–2011 vs. 2012–2019) | 0.17 | 0.14–0.22 | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Heart failure | 2.05 | 1.41–2.98 | <0.001 |

| Vascular disease | 0.97 | 0.75–1.25 | 0.805 |

| Cancer | 2.16 | 1.38–3.40 | 0.001 |

| Type of AF | |||

| Paroxysmal | 1.69 | 1.34–2.14 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding risk | |||

| HAS-BLED ≥ 3 | 1.02 | 0.80–1.30 | 0.859 |

| Reason for hospitalisation | |||

| Electrical cardioversion | 0.88 | 0.31–2.52 | 0.815 |

| Planned coronary angiography/PCI or ACS | 2.41 | 1.81–3.22 | <0.001 |

| Planned CIED implantation/reimplantation | 1.21 | 0.85–1.48 | 0.420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bielecka, B.; Gorczyca-Głowacka, I.; Ciba-Stemplewska, A.; Wożakowska-Kapłon, B. Anticoagulant Treatment in Patients with AF and Very High Thromboembolic Risk in the Era before and after the Introduction of NOAC: Observation at a Polish Reference Centre. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126145

Bielecka B, Gorczyca-Głowacka I, Ciba-Stemplewska A, Wożakowska-Kapłon B. Anticoagulant Treatment in Patients with AF and Very High Thromboembolic Risk in the Era before and after the Introduction of NOAC: Observation at a Polish Reference Centre. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126145

Chicago/Turabian StyleBielecka, Bernadetta, Iwona Gorczyca-Głowacka, Agnieszka Ciba-Stemplewska, and Beata Wożakowska-Kapłon. 2023. "Anticoagulant Treatment in Patients with AF and Very High Thromboembolic Risk in the Era before and after the Introduction of NOAC: Observation at a Polish Reference Centre" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126145

APA StyleBielecka, B., Gorczyca-Głowacka, I., Ciba-Stemplewska, A., & Wożakowska-Kapłon, B. (2023). Anticoagulant Treatment in Patients with AF and Very High Thromboembolic Risk in the Era before and after the Introduction of NOAC: Observation at a Polish Reference Centre. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126145