Dark Personality Traits and Online Behaviors: Portuguese Versions of Cyberstalking, Online Harassment, Flaming and Trolling Scales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.2.2. Psychological Variables

Internet Addiction Test

Dirty Dozen Dark Triad

Cyberstalking Scale

Online Harassment Scale

Flaming Behaviors Scale

Trolling Behaviors Scale

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

3.2. Study 1

3.2.1. Specific Objective (1) to Evaluate the Psychometric Qualities of the Instruments Used in This Study through (1a) Assessment of the Adjustment to Our Sample of Instruments Previously Validated for the Portuguese Population (Internet Addiction Test and Dirty Dozen Dark Triad)

3.2.2. Specific Objective (1) to Evaluate the Psychometric Qualities of the Instruments Used in this Study through (1b) the Validation for the Portuguese Population of the Cyberstalking Scale, Online Harassment Scale, Flaming Scale and Trolling Scale

Cyberstalking Scale

Online Harassment Scale

Flaming Behaviors Scale

Trolling Behaviors Scale

3.2.3. Correlations between Psychological Variables

3.3. Specific Objective (2) to Establish Associations between the Variables under Study and the Sociodemographic Variables

3.4. Study 2

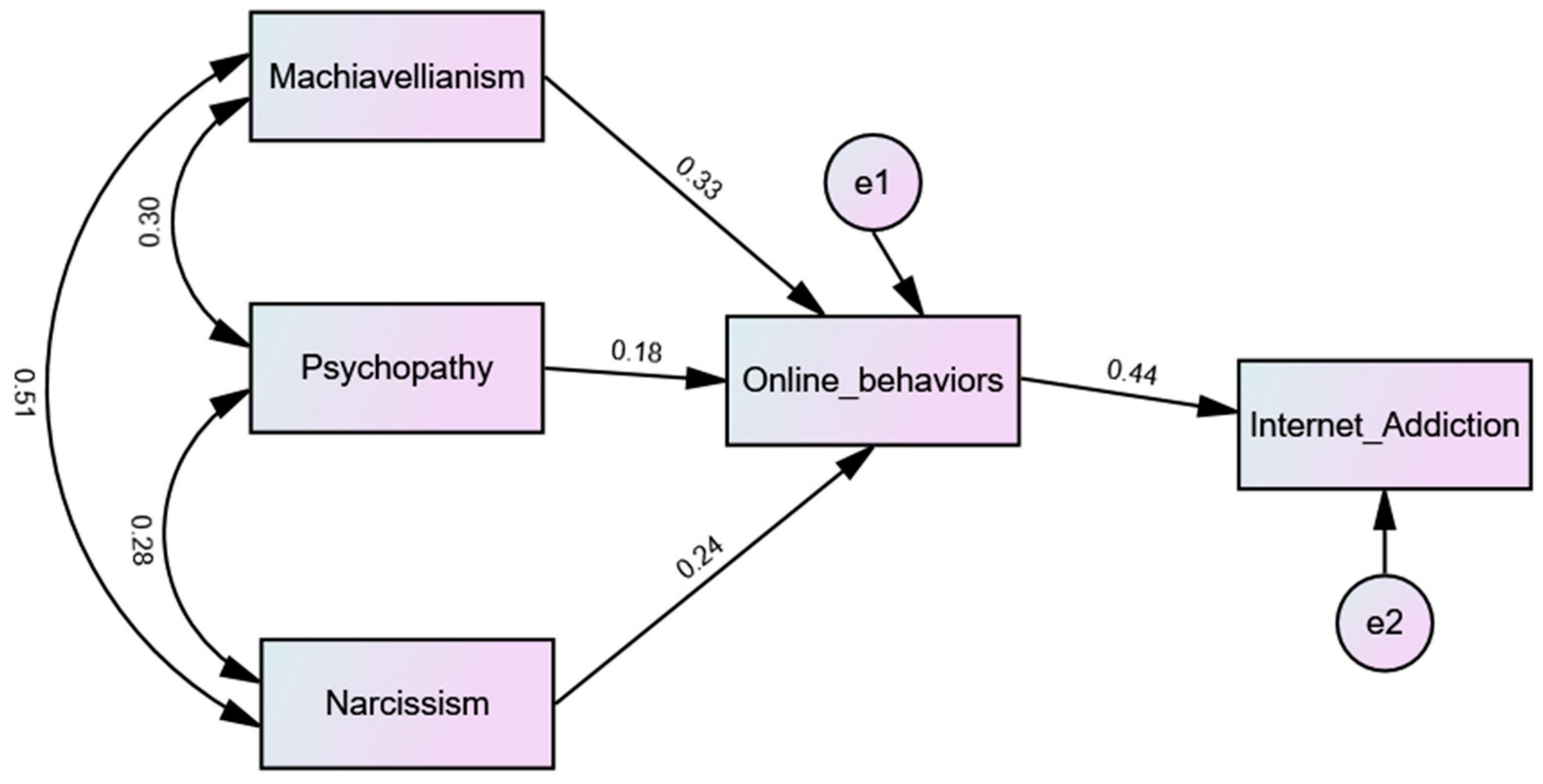

Specific Objective (3) to Look for Relationships between Personality Traits and Online Behaviors

3.5. Specific Objective (4) to Determine Whether Online Behaviors Moderate the Relation between the Dimensions of the Dark Triad of Personality and Internet Addiction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Original and Portuguese versions of the instruments validated in this study | |

| Cyberstalking Scale [51] | Escala de Cybertalking |

| 1. I usually find the social media of someone I’m interested in, even if it takes hours. | Costumo encontrar as redes sociais de alguém que me suscite interesse, mesmo que demore horas. |

| 2. It’s ok to check who likes and comments on the posts of your partner. | Acho aceitável verificar quem “gosta” e comenta os posts de um(a) parceiro(a) amoroso(a). |

| 3. I lose track of time searching for information about my acquaintances on the Internet. | Perco a noção do tempo à procura de informações acerca dos meus conhecidos na Internet. |

| 4. It is normal to “keep an eye” on the social media of someone who frequently interacts with your partner. | É normal estar atenta às redes sociais de alguém que interage frequentemente com o meu (minha) parceiro(a) amoroso (a). |

| 5. If a person hides their messages, I look for other ways to find out the content of them. | Se uma pessoa esconde muito as suas mensagens, procuro outras formas de as descobrir. |

| 6. If I had my partner’s social media passwords, my life would be easier. | Se eu tivesse as passwords das redes sociais do(a) meu(minha) parceiro(a), a minha vida seria mais fácil. |

| 7. If I could I would look at my love partner’s browsing history. | Se eu pudesse, veria o histórico de navegação do(a) meu(minha) parceiro(a) amoroso(a). |

| 8. I prefer to form relationships with people that I can investigate on social media. | Prefiro relacionar-me com pessoas que possa investigar nas redes sociais. |

| 9. I check what kind of apps my partner uses on their phone. | Verifico que tipo de aplicações o(a) meu (minha) parceiro(a) amoroso(a) utiliza no seu telemóvel. |

| 10. When you’re interested in someone, it’s not wrong to look at their acquaintances’ social media, in order to get to know them better. | Quando se está interessado em alguém, não tem mal ver as redes sociais das pessoas próximas dele(a) para conhecê-lo(a) melhor. |

| Online Harassment Scale [52] | Escala de Assédio Online |

| 1. Embarrassed on purpose. | Envergonhado(a) de propósito. |

| 2. Called offensive names. | Alvo de nomes ofensivos. |

| 3. Unwanted sexual messages. | Mensagens sexuais indesejadas. |

| 4. Threats of physical sexual violence. | Ameaças de violência sexual física. |

| 5. Threats of physical non-sexual violence. | Ameaças de violência física não sexual. |

| 6. Hurt emotionally or psychologically. | Ferido emocionalmente ou psicologicamente. |

| 7. Used information from your social media profile in a way that made you uncomfortable. | Utilizaram informações do seu perfil das redes sociais de uma forma que o(a) deixou desconfortável. |

| 8. Repeatedly contacted in a way that made you feel afraid or unsafe. | Repetidamente contactado de uma maneira que o fez sentir com medo ou inseguro(a). |

| Flaming Behaviours Scale [7] | Escala de Comportamentos de Flaming |

| 1. In the community, I tend to use swear or harsh words. (Aggression) | Na comunidade, costumo usar palavrões ou palavras duras. (Agressão) |

| 2. In the community, I tend to intimidate people who get on my nerves. (Intimidation) | Na comunidade, costumo intimidar as pessoas que me enervam. (Intimidação) |

| 3. In the community, I tend to insult people who I hate. (Insults) | Na comunidade, costumo insultar as pessoas que odeio. (Insultos) |

| 4. In the community, I tend to make vulgar jokes. (Uninhibited language) | Na comunidade, costumo fazer piadas ordinárias. (Linguagem desinibida) |

| 5. In the community, I tend to make sarcastic remarks about others opinion. (Sarcasm) | Na comunidade, costumo fazer comentários sarcásticos sobre a opinião dos outros (Sarcasmo) |

| Trolling Behaviors Scale [54] | Escala de Comportamentos de Trolling |

| 1. Debating various topics with the intention to irritate/upset others. | Debater vários tópicos com a intenção de irritar/perturbar os outros. |

| 2. Trolling’ on public forums. | Trolling em fóruns públicos. |

| 3. I like to post memes and comments with the intent to aggravate or annoy others. | Gosto de postar memes e comentários com a intenção de aborrecer ou irritar os outros. |

Appendix B

| Items description (N = 773) | ||||

| M | SD | Sk (SD = 0.088) | Kr (SD = 0.176) | |

| Internet Addiction Test Items | (0–5) | |||

| 1. Do you find that you stay on-line longer than you intended? | 3.28 | 1.05 | −0.53 | −0.09 |

| 2. Do you neglect household chores to spend more time on-line? | 2.19 | 1.15 | 0.12 | −0.48 |

| 3. Do you prefer the excitement of the Internet to intimacy with your partner? | 0.81 | 0.92 | 1.56 | 3.49 |

| 4. Do you form new relationships with fellow on-line users? | 1.72 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.14 |

| 5. Do others in your life complain to you about the amount of time you spend on-line? | 1.77 | 1.11 | 0.70 | −0.04 |

| 6. Do your grades or school work suffer because of the amount of time you spend on-line? | 1.37 | 1.16 | 0.81 | 0.33 |

| 7. Do you check your e-mail before something else that you need to do? | 2.92 | 1.20 | −0.20 | −0.56 |

| 8. Does your job performance or productivity suffer because of the Internet? | 1.82 | 1.15 | 0.56 | −0.27 |

| 9. Do you become defensive or secretive when anyone asks you what you do on-line? | 1.46 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 1.54 |

| 10. Do you block out disturbing thoughts about your life with soothing thoughts of the Internet? | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.32 | 1.73 |

| 11. Do you find yourself anticipating when you will go on-line again? | 1.45 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.50 |

| 12. Do you fear that life without the Internet would be boring, empty, and joyless? | 2.02 | 1.25 | 0.61 | −0.32 |

| 13. Do you snap, yell, or act annoyed if someone bothers you while you are on-line? | 1.38 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.63 |

| 14. Do you lose sleep due to late-night log-ins? | 2.11 | 1.28 | 0.43 | −0.69 |

| 15. Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet when off-line, or fantasize about being on-line? | 1.40 | 0.97 | 1.20 | 1.71 |

| 16. Do you find yourself saying “just a few more minutes” when on-line? | 2.49 | 1.33 | 0.06 | −0.95 |

| 17. Do you try to cut down the amount of time you spend on-line and fail? | 2.02 | 1.17 | 0.44 | −0.37 |

| 18. Do you try to hide how long you’ve been on-line? | 1.29 | 0.87 | 1.29 | 2.31 |

| 19. Do you choose to spend more time on-line over going out with others? | 1.55 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.43 |

| 20. Do you feel depressed, moody, or nervous when you are off-line, which goes away once you are back on-line? | 1.31 | 0.91 | 1.09 | 1.48 |

| Dirty Dozen Dark Triad Items | (1–5) | |||

| 1. I tend to manipulate others to get my way. | 2.43 | 1.09 | 0.33 | −0.77 |

| 2. I have used deceit or lied to get my way. | 2.58 | 1.21 | 0.13 | −1.29 |

| 3. I have use flattery to get my way. | 2.47 | 1.20 | 0.25 | −1.22 |

| 4. I tend to exploit others towards my own end. | 1.62 | 0.81 | 1.29 | 1.36 |

| 5. I tend to lack remorse. | 1.86 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 0.84 |

| 6. I tend to not be too concerned with morality or the morality of my actions. | 1.62 | 0.95 | 1.73 | 2.67 |

| 7. I tend to be callous or insensitive. | 1.95 | 1.08 | 0.91 | −0.19 |

| 8. I tend to be cynical. | 1.82 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 0.74 |

| 9. I tend to want others to admire me. | 2.61 | 1.21 | 0.10 | −1.16 |

| 10. I tend to want others to pay attention to me. | 2.68 | 1.19 | 0.05 | −1.08 |

| 11. I tend to seek prestige or status. | 2.42 | 1.23 | 0.40 | −0.95 |

| 12. I tend to expect special favors from others. | 1.81 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 0.86 |

| Cyberstalking Scale Items | (1–5) | |||

| 1. I usually find the social media of someone I’m interested in, even if it takes hours. | 2.30 | 1.26 | 0.64 | −0.78 |

| 2. It’s ok to check who likes and comments on the posts of your partner. | 2.45 | 1.17 | 0.24 | −0.97 |

| 3. I lose track of time searching for information about my acquaintances on the Internet. | 1.90 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.33 |

| 4. It is normal to “keep an eye” on the social media of someone who frequently interacts with your partner. | 2.18 | 1.13 | 0.61 | −0.57 |

| 5. If a person hides their messages, I look for other ways to find out the content of them. | 1.90 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 0.30 |

| 6. If I had my partner’s social media passwords, my life would be easier. | 1.38 | 0.70 | 1.88 | 3.11 |

| 7. If I could I would look at my love partner’s browsing history. | 1.51 | 0.86 | 1.87 | 3.32 |

| 8. I prefer to form relationships with people that I can investigate on social media. | 1.49 | 0.78 | 1.63 | 2.23 |

| 9. I check what kind of apps my partner uses on their phone. | 1.54 | 0.87 | 1.72 | 2.62 |

| 10. When you’re interested in someone, it’s not wrong to look at their acquaintances’ social media, in order to get to know them better. | 2.65 | 1.20 | −0.03 | −1.13 |

| Online Harassment Scale Items | (1–7) | |||

| 1. Embarrassed on purpose. | 1.91 | 1.21 | 1.50 | 1.93 |

| 2. Called offensive names. | 2.09 | 1.44 | 1.30 | 0.89 |

| 3. Unwanted sexual messages. | 2.30 | 1.67 | 1.11 | 0.01 |

| 4. Threats of physical sexual violence. | 1.20 | 0.69 | 4.50 | 23.47 |

| 5. Threats of physical non-sexual violence. | 1.40 | 0.94 | 2.88 | 8.98 |

| 6. Hurt emotionally or psychologically. | 2.45 | 1.58 | 0.93 | −0.06 |

| 7. Used information from your social media profile in a way that made you uncomfortable. | 1.64 | 1.18 | 2.06 | 3.70 |

| 8. Repeatedly contacted in a way that made you feel afraid or unsafe. | 1.80 | 1.27 | 1.83 | 2.93 |

| Flaming Behaviours Scale Items | (1–7) | |||

| 1. In the community, I tend to use swear or harsh words. (Aggression) | 2.20 | 1.69 | 1.30 | 0.63 |

| 2. In the community, I tend to intimidate people who get on my nerves. (Intimidation) | 1.67 | 1.22 | 2.08 | 3.98 |

| 3. In the community, I tend to insult people who I hate. (Insults) | 1.75 | 1.33 | 2.01 | 3.57 |

| 4. In the community, I tend to make vulgar jokes. (Uninhibited language) | 2.10 | 1.62 | 1.46 | 1.22 |

| 5. In the community, I tend to make sarcastic remarks about others opinion. (Sarcasm) | 2.76 | 1.84 | 0.71 | −0.66 |

| Trolling Behaviors Scale Items | (1–5) | |||

| 1. Debating various topics with the intention to irritate/upset others | 1.66 | 1.05 | 1.64 | 1.89 |

| 2. Trolling’ on public forums | 1.38 | 0.86 | 2.44 | 5.44 |

| 3. I like to post memes and comments with the intent to aggravate or annoy others | 1.65 | 1.06 | 1.59 | 1.53 |

References

- Monteiro, A.P.; Sousa, M.; Correia, E. Adição à Internet e Caraterísticas de Personalidade: Um Estudo com Estudantes Universitários Portugueses. Revista Portuguesa de Educação 2020, 33, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet addiction: A systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2014, 20, 4026–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.; Pistner, M.; O’Mara, J.; Buchanan, J. Cyber disorders: The mental health concern for the new millennium. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1999, 2, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckels, E.E.; Jones, D.N.; Paulhus, D.L. Behavioral confirmation of everyday Sadism. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.I.; Valquaresma, J. Cyberstalking: Prevalência e estratégias de coping em estudantes portugueses do ensino secundário. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana 2020, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, B.; Megan; Krysik, J. Online Harassment Among College Students: A Replication Study Incorporating New Internet Trends. 2011. Available online: http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1941065 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Turnage, A.K. Email flaming behaviors and organizational conflict. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoker, M.; March, E. Predicting perpetration of intimate partner cyberstalking: Gender and the Dark Tetrad. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuoğlu, E.; Öner-Özkan, B. Sarcastic and Deviant Trolling in Turkey: Associations with Dark Triad and Aggression. Soc. Media Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, N.; An Educator’s Guide to Cyberbullying. Center for Responsible Internet Use. 2005. Available online: http://www.cyberbully.org/docs/cbct.educators.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Nova, F.F.; Rifat, M.R.; Saha, P.; Ahmed, S.I.; Guha, S. Online sexual harassment over anonymous social media in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, Ahmedabad, India, 4–7 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashang, S.; Khanlou, N.; Clarke, J. The mental health impact of cyber sexual violence on youth identity. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, F.; Nurse, J.R.; Arief, B. Cyber stalking, cyber harassment, and adult mental health: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying, 2nd ed.; Corwin, A Sage Company: London, UK, 2015; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, L.; Anderson, J.R. A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviours. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 144, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins Norman, J. Tackling Bullying from the Inside Out: Shifting Paradigms in Bullying Research and Interventions. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2020, 2, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.K. School bullying. Sociologia Problemas e Práticas 2013, 71, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogolyubova, O.; Panicheva, P.; Tikhonov, R.; Ivanov, V.; Ledovaya, Y. Dark personalities on Facebook: Harmful online behaviors and language. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Demetrovics, Z.; Tosuntaş, Ş.B. Analyzing the links between problematic social media use, dark triad traits, and self-esteem. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Williams, K.M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 2002, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L. Toward a taxonomy of dark personalities. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Richards, S.C.; Paulhus, D.L. The Dark Triad of personality: A 10 year review. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salessi, S.; Omar, A. Propriedades psicométricas de uma escala para medir o lado escuro da personalidade. Estudos de Psicologia 2018, 35, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfá-Araujo, B.; Lima-Costa, A.R.; Hauck-Filho, N.; Jonason, P.K. Considering sadism in the shadow of the Dark Triad traits: A meta-analytic review of the Dark Tetrad. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 197, 111767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, D.; Martínez-Martínez, A.; Galán, M.; Rico-Bordera, P.; Piqueras, J.A. The Dark Tetrad and online sexual victimization: Enjoying in the distance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 142, 107659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, M.; Tiliopoulos, N. The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, M.; Giardina, A.; Coco, G.L.; Giordano, C.; Billieux, J.; Schimmenti, A. A compensatory model to understand dysfunctional personality traits in problematic gaming: The role of vulnerable narcissism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 160, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czibor, A.; Szabo, Z.P.; Jones, D.N.; Zsido, A.N.; Paal, T.; Szijjarto, L.; Carre, J.R.; Bereczkei, T. Male and female face of Machiavellianism: Opportunism or anxiety? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 117, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.D. Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. The dark side of the Internet: Preliminary evidence for the associations of dark personality traits with specific online activities and problematic Internet use. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckels, E.E.; Trapnell, P.D.; Paulhus, D.L. Trolls just want to have fun. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 67, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, B.; Yu, H. Who do you troll and Why: An investigation into the relationship between the Dark Triad Personalities and online trolling behaviours towards popular and less popular Facebook profiles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Zeng, P.; Lei, L. Social support and cyberbullying for university students: The mediating role of Internet addiction and the moderating role of stress. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.H.; Liu, T.L.; Wang, P.W.; Chen, C.S.; Yen, C.F.; Yen, J.Y. The exacerbation of depression, hostility, and social anxiety in the course of Internet addiction among adolescents: A prospective study. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindermann, C.; Sariyska, R.; Lachmann, B.; Brand, M.; Montag, C. Associations between the dark triad of personality and unspecified/specific forms of Internet-use disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alloway, T.; Runac, R.; Quershi, M.; Kemp, G. Is Facebook linked to selfishness? Investigating the relationships among social media use, empathy, and narcissism. Soc. Netw. 2014, 3, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I.; Milanovic, A.; Loboda, B.; Błachnio, A.; Przepiorka, A.; Nesic, D.; Mazic, S.; Dugalic, S.; Ristic, S. Association between physiological oscillations in self-esteem, narcissism and Internet addiction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 258, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, H.; Egan, V. The dark triad and intimate partner violence. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoire, J. ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests. Int. J. Test. 2018, 18, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-cultural research methods. In Environment and Culture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Clinical assessment of Internet-addicted clients. In Internet Addiction: A Handbook and Guide to Evaluation and Treatment; Young, K., Abreu, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K. Caught in the Net: How to Recognize the Signs of Internet Addiction; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Widyanto, L.; McMurran, M. The psychometric properties of the Internet addiction test. Cyberpsychology Behav. 2004, 7, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, H.K.; Gyeong, H.; Yu, B.; Song, Y.M.; Kim, D. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Internet Addiction Test among college students. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, H. Internet addiction in Japanese college students: Is Japanese version of Internet Addiction Test (JIAT) useful as a screening tool. Bull. Senshu Univ. Sch. Hum. Sci. 2013, 3, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, H.M.; Patrão, I.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Portuguese validation of the Internet Addiction Test: An empirical study. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Webster, G.D. The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess 2010, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechorro, P.; Jonason, P.K.; Raposo, V.; Maroco, J. Dirty Dozen: A concise measure of Dark Triad traits among at-risk youths. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3522–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Santos, I.L.; Pimentel, C.E.; Mariano, T.E. Cyberstalking scale: Development and relations with gender, FOMO and social media engagement. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 4802–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.C.; Zamith, R.; Coddington, M. Online harassment and its implications for the journalist–audience relationship. Digit. J. 2020, 8, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Cyber neutralisation and flaming. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, K.; Zolnierek, K.H.; Critz, K.; Dailey, S.; Ceballos, N. An examination of psychosocial factors associated with malicious online trolling behaviors. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 149, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 6, pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Benesty, J.; Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Cohen, I. Pearson Correlation Coefficient. Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’connor, B.P. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2000, 32, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, S.; Skewness | Definition, Examples & Formula. Scribbr. 2022. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/skewness/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Buckner, J.; Castille, C.; Sheets, T. The five-factor model of personality and employees’ excessive use of technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, Z.A.; Marchlewska, M.; Rogoza, M.; Michalski, P.; Górska, P.; Szczepańska, D.; Cislak, A. What makes an Internet troll? On the relationships between temperament (BIS/BAS), Dark Triad, and Internet trolling. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much time do you dedicate to the Internet per day, in non-academic or professional tasks? | 1 | Up to 2 h | 185 | 23.9 |

| 2 | Between 2 to 4 h | 253 | 32.7 | |

| 3 | Between 4 to 6 h | 234 | 30.3 | |

| 4 | More than 6 h | 101 | 13.1 | |

| Identify how you use the Internet (excluding academic or professional tasks). | ||||

| No | Yes | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| 1—Consult email | 102 | 13.2 | 671 | 86.8 |

| 2—Social networks | 23 | 3.0 | 750 | 97.0 |

| 3—Listen to music online | 85 | 11.0 | 688 | 89.0 |

| 4—Looking for new friends | 622 | 80.5 | 151 | 19.5 |

| 5—Search for information and news in general | 98 | 12.7 | 675 | 87.3 |

| 6—Play online | 475 | 61.4 | 298 | 38.6 |

| 7—Communicate and relate to others | 81 | 10.5 | 692 | 89.5 |

| 8—Online shopping | 263 | 34.0 | 510 | 66.0 |

| 9—Digress on the Internet | 223 | 28.8 | 550 | 71.2 |

| 10—Watch movies/series | 159 | 20.6 | 614 | 79.4 |

| 11—Betting sites | 679 | 87.8 | 94 | 12.2 |

| 12—Search for adult content | 598 | 77.4 | 175 | 22.6 |

| (N = 387) (10 Items) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| h2 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| Control | Justification | Time | ||

| 1. I usually find the social media of someone I’m interested in, even if it takes hours. | 0.704 | 0.034 | 0.280 | 0.791 |

| 2. It’s ok to check who likes and comments on the posts of your partner. | 0.741 | 0.093 | 0.837 | 0.177 |

| 3. I lose track of time searching for information about my acquaintances on the Internet. | 0.738 | 0.228 | 0.151 | 0.814 |

| 4. It is normal to “keep an eye” on the social media of someone who frequently interacts with your partner. | 0.747 | 0.169 | 0.841 | 0.107 |

| 5. If a person hides their messages, I look for other ways to find out the content of them. | 0.515 | 0.350 | 0.617 | 0.108 |

| 6. If I had my partner’s social media passwords, my life would be easier. | 0.750 | 0.839 | 0.206 | 0.070 |

| 7. If I could I would look at my love partner’s browsing history. | 0.711 | 0.791 | 0.291 | 0.019 |

| 8. I prefer to form relationships with people that I can investigate on social media. | 0.702 | 0.702 | −0.015 | 0.457 |

| 9. I check what kind of apps my partner uses on her/his phone. | 0.562 | 0.678 | 0.282 | 0.153 |

| 10. When you’re interested in someone, it’s not wrong to look at their acquaintances’ social media, in order to get to know them better. | 0.537 | 0.271 | 0.620 | 0.281 |

| Eigenvalues | 4.32 | 1.30 | 1.10 | |

| Total variance explained (67.07%) | 43.23 | 12.98 | 10.87 | |

| Cronbach’s alfa (α) | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.65 |

| Correlation matrix range [0.30–0.90] | 0.19–0.69 | |||

| Determinant score [above 0.00001] | 0.023 | |||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (df); p < 0.05 | 1441.77 (45); <0.001 | |||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (KMO) (above 0.50) | 0.846 | |||

| Diagonal element anti-correlation matrix (above 0.50) | 0.81–0.91 | |||

| Pearson’s Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | CR | AVE | Mean (Standard Deviation) | |

| 1. Cyberstalking Total | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 1.93 (0.66) | |||

| 2. Cyberstalking Control | 0.80 ** | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 1.48 (0.64) | ||

| 3. Cyberstalking Justification | 0.89 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 2.30 (0.89) | |

| 4. Cyberstalking Time | 0.69 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 2.10 (0.97) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adiction Internet Total | |||||||||||

| 2. Dirty Dozen Machiavellianism | 0.336 ** | ||||||||||

| 3. Dirty Dozen Psychopathy | 0.168 ** | 0.300 ** | |||||||||

| 4. Dirty Dozen Narcissism | 0.254 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.278 ** | ||||||||

| 5. Cyberstalking Total | 0.358 ** | 0.399 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.430 ** | |||||||

| 6. Cyberstalking Control | 0.234 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.803 ** | ||||||

| 7. Cyberstalking Justification | 0.290 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.181 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.892 ** | 0.554 ** | |||||

| 8. Cyberstalking Time | 0.372 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.150 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.452 ** | ||||

| 9. Online Harassment Total | 0.319 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.309 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.307 ** | |||

| 10. Flaming Total | 0.291 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.378 ** | ||

| 11. TrollingTotal | 0.221 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.224 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.535 ** | |

| Skweness | 0.212 | 0.188 | 0.983 | 0.212 | 0.640 | 1.424 | 0.457 | 0.688 | 1.547 | 1.404 | 1.744 |

| Kurtosis | 0.100 | −0.715 | 0.632 | −0.712 | −0.053 | 1.827 | −0.297 | −0.354 | 2.918 | 1.658 | 2.650 |

| Tolerance | 0.626 | 0.813 | 0.662 | 0.877 | 0.639 | 0.587 | 0.713 | 0.761 | 0.606 | 0.686 | |

| VIF | 1.598 | 1.230 | 1.511 | 1.140 | 1.564 | 1.704 | 1.402 | 1.314 | 1.649 | 1.457 |

| Sex | N | M | SD | t(771) | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adiction Internet Total | Man | 306 | 1.78 | 0.67 | −0.11 | 0.910 | 0.64 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.79 | 0.62 | ||||

| 2. Dirty Dozen Machiavellianism | Man | 306 | 2.36 | 0.82 | 2.47 | 0.014 | 0.80 |

| Woman | 467 | 2.22 | 0.80 | ||||

| 3. Dirty Dozen Psychopathy | Man | 306 | 1.93 | 0.78 | 3.48 | <0.001 | 0.72 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.74 | 0.68 | ||||

| 4. Dirty Dozen Narcissism | Man | 306 | 2.50 | 0.95 | 2.92 | 0.004 | 0.92 |

| Woman | 467 | 2.30 | 0.90 | ||||

| 5. Cyberstalking Total | Man | 306 | 1.85 | 0.62 | −2.87 | 0.004 | 0.65 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.98 | 0.68 | ||||

| 6. Cyberstalking Control | Man | 306 | 1.51 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.322 | 0.64 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.46 | 0.64 | ||||

| 7. Cyberstalking Justification | Man | 306 | 2.15 | 0.79 | −3.89 | <0.001 | 0.89 |

| Woman | 467 | 2.39 | 0.94 | ||||

| 8. Cyberstalking Time | Man | 306 | 1.92 | 0.88 | −4.11 | <0.001 | 0.96 |

| Woman | 467 | 2.21 | 1.01 | ||||

| 9. Online Harassment Total | Man | 306 | 1.78 | 0.76 | −1.97 | 0.049 | 0.87 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.90 | 0.94 | ||||

| 10. Flaming Total | Man | 306 | 2.48 | 1.42 | 6.66 | <0.001 | 1.22 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.85 | 1.06 | ||||

| 11. TrollingTotal | Man | 306 | 1.78 | 0.93 | 5.70 | <0.001 | 0.80 |

| Woman | 467 | 1.42 | 0.70 |

| Romantic Relationship | N | M | SD | t(771) | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adiction Internet Total | No | 331 | 1.97 | 0.63 | 7.19 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.65 | 0.61 | ||||

| 2. Dirty Dozen Machiavellianism | No | 331 | 2.29 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.548 | 0.81 |

| Yes | 442 | 2.26 | 0.81 | ||||

| 3 Dirty Dozen Psychopathy | No | 331 | 1.89 | 0.77 | 2.41 | 0.016 | 0.73 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.76 | 0.69 | ||||

| 4. Dirty Dozen Narcissism | No | 331 | 2.38 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.969 | 0.93 |

| Yes | 442 | 2.38 | 0.93 | ||||

| 5. Cyberstalking Total | No | 331 | 1.95 | 0.61 | 0.89 | 0.371 | 0.66 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.91 | 0.69 | ||||

| 6. Cyberstalking Control | No | 331 | 1.48 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.975 | 0.64 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.48 | 0.65 | ||||

| 7. Cyberstalking Justification | No | 331 | 2.25 | 0.78 | −1.30 | 0.193 | 0.89 |

| Yes | 442 | 2.33 | 0.97 | ||||

| 8. Cyberstalking Time | No | 331 | 2.31 | 0.98 | 5.35 | <0.001 | 0.96 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.94 | 0.93 | ||||

| 9. Online Harassment Total | No | 331 | 1.94 | 0.85 | 2.63 | 0.009 | 0.87 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.78 | 0.88 | ||||

| 10. Flaming Total | No | 331 | 2.21 | 1.24 | 2.07 | 0.039 | 1.25 |

| Yes | 442 | 2.02 | 1.26 | ||||

| 11. TrollingTotal | No | 331 | 1.61 | 0.84 | 1.36 | 0.176 | 0.82 |

| Yes | 442 | 1.53 | 0.81 |

| β (t) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberstalking Total | Cyberstalking Control | Cyberstalking Justification | Cyberstalking Time | Online Harassment | Flaming | Trolling | ||

| Block 1 | Gender | 0.163 (5.222) *** | 0.023 (0.679) ns | 0.185 (5.734) *** | 0.182 (5.579) *** | 0.095 (2.913) ** | −0.200 (−6.491) *** | −0.169 (−5.119) *** |

| Age | −0.075 (−2.353) * | 0.075 (2.185) * | −0.098 (−2.974) ** | −0.172 (−5.160) *** | −0.286 (−8.594) *** | −0.238 (−7.590) *** | −0.123 (−3.632) *** | |

| Block 2 | Machiavellianism | 0.214 (5.766) *** | 0.173 (4.347) *** | 0.175 (4.585) *** | 0.174 (4.486) *** | 0.250 (6.472) *** | 0.216 (5.901) *** | 0.180 (4.587) *** |

| Psychopathy | 0.101 (3.049 ** | 0.161 (4.532) *** | 0.055 (1.617) ns | 0.029 (0.832) ns | 0.060 (1.720) ns | 0.195 (5.976) *** | 0.159 (4.538) *** | |

| Narcissism | 0.301(8.287) *** | 0.205 (5.250) *** | 0.286 (7.630) *** | 0.225 (5.907) *** | 0.016 (0.422) ns | 0.059 (1.655) ns | 0.079 (2.048) * | |

| R2adj | 0.264 | 0.154 | 0.217 | 0.195 | 0.198 | 0.285 | 0.174 | |

| F(3, 767) | 79.874 | 47.901 | 56.575 | 38.815 | 23.945 | 44.122 | 24.591 | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leite, Â.; Cardoso, S.; Monteiro, A.P. Dark Personality Traits and Online Behaviors: Portuguese Versions of Cyberstalking, Online Harassment, Flaming and Trolling Scales. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126136

Leite Â, Cardoso S, Monteiro AP. Dark Personality Traits and Online Behaviors: Portuguese Versions of Cyberstalking, Online Harassment, Flaming and Trolling Scales. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126136

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeite, Ângela, Susana Cardoso, and Ana Paula Monteiro. 2023. "Dark Personality Traits and Online Behaviors: Portuguese Versions of Cyberstalking, Online Harassment, Flaming and Trolling Scales" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126136

APA StyleLeite, Â., Cardoso, S., & Monteiro, A. P. (2023). Dark Personality Traits and Online Behaviors: Portuguese Versions of Cyberstalking, Online Harassment, Flaming and Trolling Scales. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126136