Dealing with Alcohol-Related Posts on Social Media: Using a Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Young Peoples’ Problem Awareness and Evaluations of Intervention Ideas

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Effects of Alcohol Posts on Drinking Behavior

1.2. The Importance of Problem Awareness

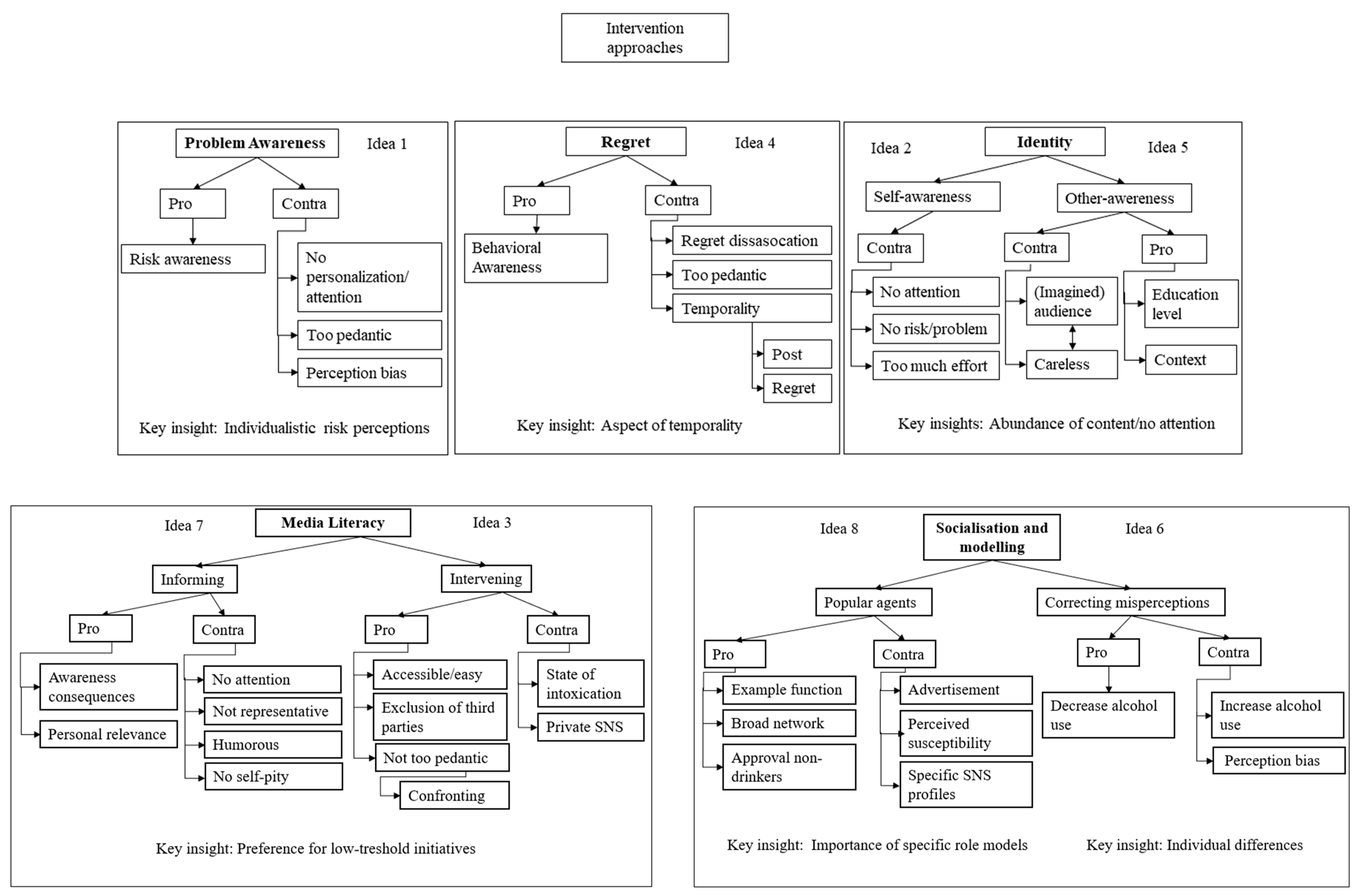

1.3. Intervention Ideas to Decrease (the Effects of) Alcohol Posts

1.3.1. Idea 1: Alcohol-Post Problem

1.3.2. Idea 2: (Too) Many Alcohol Posts

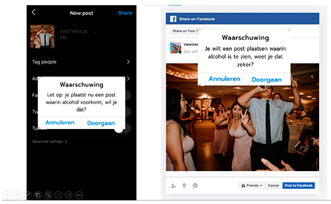

1.3.3. Idea 3: Warning Alcohol Posts

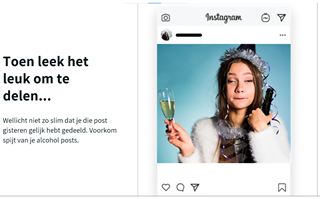

1.3.4. Idea 4: Regret Alcohol Posts

1.3.5. Idea 5: Perceived Identity of Alcohol Posts

1.3.6. Idea 6: Correcting Misperceived Norms

1.3.7. Idea 7: Alcohol Posts Are Unrealistic

1.3.8. Idea 8: Popular Young People

1.4. Individual Differences in Problem Awareness and Intervention Evaluations

2. Methods

2.1. Method Study 1 (Qualitative Study)

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Procedure

2.1.3. Analysis

2.2. Method Study 2 (Quantitative Study)

2.2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2.2. Measures

3. Results

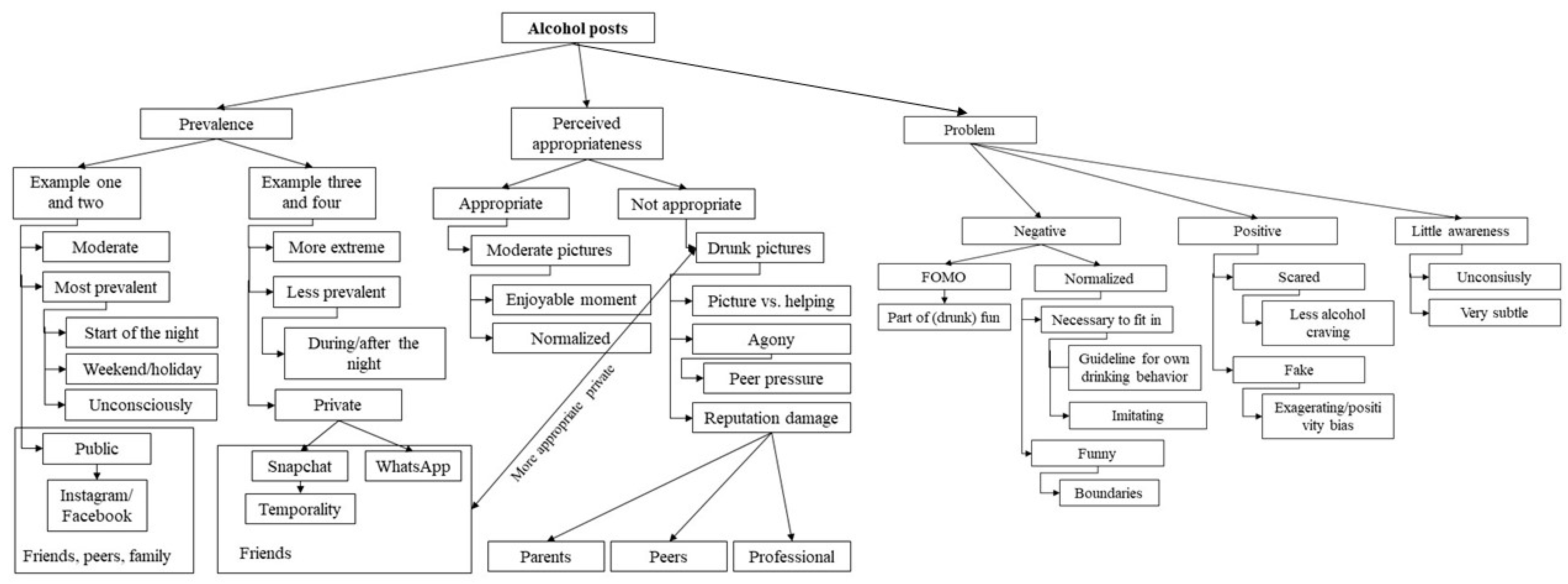

3.1. Results Study 1 (Qualitative Study)

3.1.1. Alcohol Post Prevalence, Perceived Appropriateness, and Problem Awareness

Focus Group 5, university students

- Ciara (Female, 25 years old):

- “Um, yeah. What do I think, I thought 1, that’s, I think it’s nice, just to see it. 2 also, specifically when someone has something to celebrate, for example, I think: ah, yes, nice! That’s just, it remains with one drink, so yes. But if you show a whole table, I don’t know, with all kinds of beer or alcohol, then I think, okay, what are you doing? And especially with a picture or a video of someone who is so wasted that he can’t even stand normally on his legs anymore. Then I really think, Yes, that is just super stupid.”

Focus Group 4, university students

- Atiyah (Female, 26 years old):

- “Yes. I think it’s tricky because young people probably don’t even know that they’re influenced by these posts. Like, I wasn’t even aware until you told me right now. Like, I wasn’t aware of that. Only when I started thinking about it, I was like: Oh yeah, wait, it could have an impact.”

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “The other day, I saw a photo of a birthday party where they had a lot of bottles of alcohol. And then you’re more inclined to think: ‘Oh, I’m also having a party soon, so I must have as much as they are having,’ because it’s a bit normal to have so much.”

3.1.2. Intervention Ideas Proposed by Participants

Focus Group 5, university students

- Ciara (Female, 25 years old):

- “I think you should just really start to actually reduce alcohol consumption in general, or maybe you should develop an app or something, so that you can, for example, start fading alcoholic drinks.”

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “Hey, but I wouldn’t take a picture of an ugly bottle either. You put that one in the back anyway.”

Focus Group 4, university students

- Atiyah (Female, 26 years old):

- “Look, you have to give a convincing reason not to post something. I mean, you can say, ‘Yeah, it’s not cool!’ or whatever, but young people are always going to think booze is cool. Even more if you ban it. [Silence.]”

3.1.3. Perceptions of Theoretically Proposed Intervention Ideas

Idea 1: Alcohol-Post Problem

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Erin (Female, 17 years old):

- “I’m always sensitive to those percentages, though.”

Focus Group 3, high-school students

- Jerry (Male, 17 years old):

- “I personally think that a 15 percent increased chance is not captivating for most people.”

Focus Group 6, university students

- Hugh (Male, 20 years old):

- “15 percent might not say that much to people.”

Focus Group 3, high-school students

- Tanya (Female, 16 years old):

- “Then yes, you should put a picture, but you shouldn’t put the sentence like ‘15 percent of young people have started drinking more,’ that would, ….just no. That doesn’t do anything for me.”

Idea 2: (Too) Many Alcohol Posts

Focus Group 3, high-school students

- Humberto (Male, 16 years old):

- “I don’t think it really does anything to anybody.”

- Jerry (Male, 17 years old):

- “No, because when you see all those pictures, you don’t realize what the consequences were of those pictures.”

Idea 3: Warning Alcohol Posts

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Chantal (Female, 17 years old):

- “I do think it’s a good idea. I also think that if, for example, every time you get a message saying, ‘You’re posting something with alcohol on it,’ then at a certain point, you realize, ‘OK, so there’s something wrong with it, and you’re already spreading information with it.’”

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “So you inform the sender and the receiver of the post. That you slow it down a bit on both sides.”

Focus Group 6, university students

- Hugh (Male, 20 years old):

- “I thought this machine learning, I thought that was pretty smart. I think, if you want to post something, and it says, ‘Yo. There’s also alcohol in here and stuff’ that you’d think about it for a second, one second longer.”

Idea 4: Regret Alcohol Posts

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Chantal (Female, 17 years old):

- “I think it’s a good idea, but I personally always have, the day after I’ve been drinking and I have a hungover, I always regret it. But it’s always a short moment; the next day it’s always over.”

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “I always like it when I see those photos again. When I wake up in the morning and think, okay, that was a good party.”

- Interviewer:

- “Then you don’t think, ‘Naaah, regret?’”

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “Well, when everyone has seen that picture, then I always think ‘Okay.... this is great (sarcastic).’”

- Chantal (Female, 17 years old):

- “I don’t know. But the regret passes so quickly, too.”

- Erin (Female, 17 years old):

- “Yeah, I have that too.”

- Barry (Male, 19 years old):

- “Yes, regret quickly turns into laughter. You start laughing about it, and then you take a picture like that again.”

Idea 5: Perceived Identity of Alcohol Posts

Focus Group 5, university students

- Ciara (Female, 25-years-old):

- “I also think that when you go out until very late every weekend and so on, your parents might already have an idea like, ‘Well, there’s no way she’s going to drink coke all night.’ Those people are already a little closer to you, so maybe you are less interested in what they think. Or then you don’t worry about it that much, unlike, for example, an employer of yours, or I don’t know, the in-laws or something. I have no idea, but yeah, people who are a little bit farther away from you.”

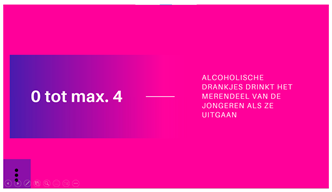

Idea 6: Correcting Misperceived Norms

Focus Group 6, university students

- Jan (Male, 22 years old):

- “Because I think a lot of young people have the opinion that if they go out and drink 0 to 4 drinks, that’s not an excessive amount at all.”

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Andrea (Female, 18 years old):

- “I think specifically this example doesn’t work because it says here that the majority of young people drink 0 to 4 drinks. And so it indicates that the majority of young people drink. Well, only 4, but they do drink.”

Focus Group 4, university students

- Atiyah (Female, 26 years old):

- “You know, you can be a responsible drinker and still post alcoholposts. You don’t have to get wasted, because in your examples you had very decent ones (alcoholposts) too.”

Idea 7: Alcohol Posts Are Unrealistic

Focus Group 3, high-school students

- Tanya (Female, 16 years old):

- “Well, it’s very confronting.”

- Lorenzo (Male, 16 years old):

- “Yes, confronting.”

- Tanya (Female, 16 years old):

- “I think so. You first see a girl who has put on makeup, all pretty, she goes for a drink and the next thing she is throwing up.”

- Interviewer:

- “This works for you?”

- Tanya (Female, 16 years old):

- “Yes, yes, because I don’t think about it that often. When I see a picture, I think, ‘Oh! Fun moment!’ But then maybe half an hour later, she’s lying there arguing because they all had too much … Well, I don’t think about that.”

Idea 8: Popular Young People

Focus Group 1, high-school students

- Barry (Male, 19 years old):

- “This is already happening, right? That influencers are used? It’s good, though, because little kids look up to these kinds of influencers.”

- Erin (Female, 17 years old):

- “Yes, but I don’t know if it helps?”

- Barry (Male, 19 years old):

- “When you see Lil Kleine posting this.... Yeah, Lil Kleine is not credible, either.”

- Gabrielle (Female, 17 years old):

- “I would not go for Lil Kleine because he is someone who often drinks himself anyway.”

3.2. Results Study 2 (Quantitative Study)

3.2.1. Problem Awareness Alcohol Posts

3.2.2. Ranking and Perceived Effectiveness

3.2.3. How Problem Awareness and Ranking Depend on Characteristics

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group ID | Name | Sex | Age 1 | Educational Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents in high school (n = 16) | ||||

| 1 | Andrea | Female | 18 | Vwo (final year) |

| 1 | Chantal | Female | 17 | Vwo (final year) |

| 1 | Erin | Female | 17 | Vwo (final year) |

| 1 | Barry | Male | 19 | Vwo (final year) |

| 1 | Gabrielle | Female | 17 | Vwo (final year) |

| 1 | Imelda | Female | 18 | Vwo (final year) |

| 2 | Karen | Female | 16 | Havo (penultimate year) |

| 2 | Melissa | Female | 16 | Havo (penultimate year) |

| 2 | Olga | Female | 16 | Havo (penultimate year) |

| 2 | Dorian | Male | 16 | Havo (penultimate year) |

| 3 | Rebekah | Female | 16 | Havo (final year) |

| 3 | Fernand | Male | 17 | Havo (final year) |

| 3 | Humberto | Male | 16 | Havo (final year) |

| 3 | Jerry | Male | 17 | Havo (final year) |

| 3 | Lorenzo | Male | 16 | Havo (final year) |

| 3 | Tanya | Female | 16 | Havo (final year) |

| Young adults at university (n = 11) | ||||

| 4 | Brendan | Male | 28 | University (master) |

| 4 | Atiyah | Female | 26 | University (master) |

| 5 | Ciara | Female | 25 | University (master) |

| 5 | Dennis | Male | 22 | University (pre-master) |

| 5 | Francis | Male | 21 | University (bachelor) |

| 6 | Hugh | Male | 20 | University (bachelor) |

| 6 | Ellen | Female | 20 | University (bachelor) |

| 6 | Jan | Male | 22 | University (master) |

| 7 | Gerda | Female | 22 | University (bachelor) |

| 7 | Liam | Male | 24 | University (master) |

| 7 | Iris | Female | 19 | University (bachelor) |

| Focus Group ID | n | Date | Duration (Minutes) | Remarks/Irregularities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-School Students | ||||

| FG 1 | 6 | 29 November 2019 | 26:08 min | All from the same class; two are good friends |

| FG 2 | 6 | 29 November 2019 | 25:52 min | All from the same class. Two participants were below the age range and were removed from the analysis procedure. Interviewer had to put in a lot of effort to keep the group in check and get answers. |

| FG 3 | 6 | 29 November 2019 | 42:14 min | Participants from different classes. Seemed to be good friends. |

| University students | ||||

| FG 4 | 2 | 06 December 2019 | 22:38 min | Three students canceled last minute. Participants knew interviewer. |

| FG 5 | 3 | 07 December 2019 | 41:15 min | Participants knew each other from shared hobby. |

| FG 6 | 3 | 16 December 2019 | 28:27 min | Short session because participants had obligatory classes and because participants arrived late. |

| FG 7 | 3 | 16 December 2019 | 31:23 min | Short session (similar reasons as FG 5). |

Appendix B. Focus-Group Interview Guide (Translated to English)

- Do you ever post such messages on social media? (If “yes,” continue to ask, how often do you place alcohol posts on average?)

- Do you ever see alcohol posts posted by your friends on social media? (If “yes,” how often? What do you see then/what kinds of posts?)

- Do you follow influencers who post such alcohol posts? (If “yes,” how often? What kinds of posts?)

- What do you think of seeing alcohol posts?

- To what extent do you think alcohol posts are a problem? And why? [Keep discussion short.]

- There has been research conducted into the effects of alcohol posts, what do you think researchers have found?

- Supposing you sometimes post alcohol posts, how could we ensure that you post fewer alcohol posts?

- Supposing you sometimes see alcohol posts, how could we ensure that you are less influenced by alcohol posts?

- Could you rank these ideas from best (or most convincing) to the worst idea?

- What do you like about this idea? What do you dislike about this idea?

- What could we add to these ideas to enhance these campaigns according to you?

- After a joint discussion about each idea, ask participants to create a top three with the group.

- Do you have more tips for us (that are not mentioned yet)?

- Imagine that you think the following: “if you do not want me to post this anymore, then you really must do this or that,” or “if you want me to be less influenced about alcohol posts, then you need to address this or that.”

Appendix C. Examples and Descriptions of Alcohol-Related Posts (Translated to English)

| Example 1 1 | Example 2 2 | Example 3 3 | Example 4 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| This is a post in which alcohol is more or less accidentally showcased because you or others are holding or drinking alcoholic beverages (e.g., photos of a dinner party or party). | This is a post where alcohol is shown a bit more prominently (zooming in on 1 drink). | This is a post where someone is very tipsy or drunk. | This is a post referring to a drinking game. |

|  |  |  |

References

- Vanherle, R.; Hendriks, H.; Beullens, K. Only for Friends, Definitely Not for Parents: Adolescents’ Sharing of Alcohol References on Social Media Features. Mass Commun. Soc. 2022, 26, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niland, P.; Lyons, A.C.; Goodwin, I.; Hutton, F. ‘See it doesn’t look pretty does it?’ Young adults’ airbrushed drinking practices on Facebook. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, H.; Putte, B.V.D.; Gebhardt, W.A. Alcoholposts on Social Networking Sites: The Alcoholpost-Typology. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.L.; Lookatch, S.J.; Ramo, D.E.; McKay, J.R.; Feinn, R.S.; Kranzler, H.R. Meta-Analysis of the Association of Alcohol-Related Social Media Use with Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, H.W. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 2002, 14, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Leefstijl en (Preventief) Gezondheidsonderzoek; Persoonskenmerken. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/cijfers/detail/83021NED (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Boyle, S.C.; LaBrie, J.W.; Baez, S.; Taylor, J.E. Integrating social media inspired features into a personalized normative feedback intervention combats social media-based alcohol influence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 228, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridout, B.; Campbell, A. Using Facebook to deliver a social norm intervention to reduce problem drinking at university. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeals: Implications for Effective Public Health Campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and the Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, F.; Beullens, K. Triple spirals? A three-wave panel study on the longitudinal associations between social media use and young individuals’ alcohol consumption. Media Psychol. 2020, 24, 766–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribner, R.A.; Theall, K.P.; Mason, K.; Simonsen, N.; Schneider, S.K.; Towvim, L.G.; DeJong, W. Alcohol Prevention on College Campuses: The Moderating Effect of the Alcohol Environment on the Effectiveness of Social Norms Marketing Campaigns. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 72, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, M.T.; Mcbride, N.T.; Sumnall, H.R.; Cole, J.C. Reducing the harm from adolescent alcohol consumption: Results from an adapted version of SHAHRP in Northern Ireland. J. Subst. Use 2012, 17, 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riper, H.; van Straten, A.; Keuken, M.; Smit, F.; Schippers, G.; Cuijpers, P. Curbing Problem Drinking with Personalized-Feedback Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erevik, E.K.; Torsheim, T.; Vedaa, Ø.; Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Sharing of Alcohol-Related Content on Social Networking Sites: Frequency, Content, and Correlates. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 78, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, C.T.; Kim, Y.; Valov, J.J.; Rosenbaum, J.E.; Johnson, B.K.; Hancock, J.T.; Gonzales, A.L. An Explication of Identity Shift Theory. J. Media Psychol. 2021, 33, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, K.; Rimal, R.N. Friends Talk to Friends About Drinking: Exploring the Role of Peer Communication in the Theory of Normative Social Behavior. Health Commun. 2007, 22, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, D.M.; Stock, M.L. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: The roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011, 25, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, S.C.; Smith, D.J.; Earle, A.M.; Labrie, J.W. What “likes” have got to do with it: Exposure to peers’ alcohol-related posts and perceptions of injunctive drinking norms. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 66, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurten, S.; Vanherle, R.; Beullens, K.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Putte, B.V.D.; Hendriks, H. Like to drink: Dynamics of liking alcohol posts and effects on alcohol use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 121–153. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.A.; Whitehill, J.M. Influence of Social Media on Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Young Adults. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2014, 36, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of travel demand management measures: The importance of problem awareness, personal norm, freedom, and fairness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, C.; Manthey, J.; Martinez, A.; Rehm, J. Alcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: A cross-sectional study in European primary care practices. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2015, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, E.S.; Skobic, I.; Valdez, L.; Garcia, D.O.; Korchmaros, J.; Stevens, S.; Sabo, S.; Carvajal, S. Youth Participatory Action Research for Youth Substance Use Prevention: A Systematic Review. Subst. Use Misuse 2019, 55, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist-Grantz, R.; Abraczinskas, M. Using Youth Participatory Action Research as a Health Intervention in Community Settings. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 21, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernick, L.J.; Woodford, M.R.; Kulick, A. LGBTQQ Youth Using Participatory Action Research and Theater to Effect Change: Moving Adult Decision-Makers to Create Youth-Centered Change. J. Community Pract. 2014, 22, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Greenfield, P.M. Virtual worlds in development: Implications of social networking sites. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Williams, G.C.; Resnicow, K. Toward systematic integration between self-determination theory and motivational interviewing as examples of top-down and bottom-up intervention development: Autonomy or volition as a fundamental theoretical principle. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, F.; Beullens, K. The reciprocal associations between sharing alcohol references on social networking sites and binge drinking: A longitudinal study among late adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geber, S.; Frey, T.; Friemel, T.N. Social Media Use in the Context of Drinking Onset: The Mutual Influences of Social Media Effects and Selectivity. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, H.; de Nooy, W.; Gebhardt, W.A.; van den Putte, B. Causal effects of alcohol-related Facebook posts on drinking behavior: Longitudinal experimental study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, H.; Gebhardt, W.A.; van den Putte, B.; Han, S.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, J.H.; Pegg, K.J.; O’Donnell, A.W.; Lala, G. Alcohol-Related Posts from Young People on Social Networking Sites: Content and Motivations. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlinghaus, K.R.; Johnston, C.A. Advocating for Behavior Change with Education. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 12, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, F.; Beullens, K. Self-Reported versus Actual Alcohol-Related Communication on Instagram: Exploring the Gap. Health Commun. 2021, 38, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compernolle, S.; Desmet, A.; Poppe, L.; Crombez, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Cardon, G.; Van Der Ploeg, H.P.; Van Dyck, D. Effectiveness of interventions using self-monitoring to reduce sedentary behavior in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, K.; Blair, S.; Busam, J.A.; Forstner, S.; Glance, J.; Green, G.; Kawata, A.; Kovvuri, A.; Martin, J.; Morgan, E.; et al. Real Solutions for Fake News? Measuring the Effectiveness of General Warnings and Fact-Check Tags in Reducing Belief in False Stories on Social Media. Polit. Behav. 2019, 42, 1073–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijt, J.; Meppelink, C.S.; Vandeberg, L. Stop and Think! Exploring the Role of News Truth Discernment, Information Literacy, and Impulsivity in the Effect of Critical Thinking Recommendations on Trust in Fake COVID-19 News. Eur. J. Health Commun. 2022, 3, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, T.; Bonela, A.A.; He, Z.; Angus, D.; Carah, N.; Kuntsche, E. Connected and consuming: Applying a deep learning algorithm to quantify alcoholic beverage prevalence in user-generated instagram images. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2021, 29, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, F.; Vranken, I. Drink, Share, and Comment; Wait, What Did I Just Do? Understanding Online Alcohol-Related Regret Experiences Among Emerging Adults. J. Drug Issues 2021, 51, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfer, L. They shouldn’t post that! Student perception of inappropriate posts on Facebook regarding alcohol consumption and the implications for peer socialization. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Sniehotta, F.; Schüz, B. Predicting binge-drinking behaviour using an extended TPB: Examining the impact of anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, H.; Putte, B.V.D.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Moreno, M.A. Social Drinking on Social Media: Content Analysis of the Social Aspects of Alcohol-Related Posts on Facebook and Instagram. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreurs, L.; Vandenbosch, L. Introducing the Social Media Literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. J. Child. Media 2020, 15, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostygina, G.; Tran, H.; Binns, S.; Szczypka, G.; Emery, S.; Vallone, D.; Hair, E. Boosting Health Campaign Reach and Engagement Through Use of Social Media Influencers and Memes. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120912475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Weber, K.M.; Vail, R.G. The Relationship Between the Perceived and Actual Effectiveness of Persuasive Messages: A Meta-Analysis with Implications for Formative Campaign Research. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremers, S.P.; de Bruijn, G.-J.; Droomers, M.; van Lenthe, F.; Brug, J. Moderators of Environmental Intervention Effects on Diet and Activity in Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, P.; Stice, E.; Shaw, H.; Gau, J.M.; Ohls, O.C. Age effects in eating disorder baseline risk factors and prevention intervention effects. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobel, S.; Wirt, T.; Schreiber, A.; Kesztyüs, D.; Kettner, S.; Erkelenz, N.; Wartha, O.; Steinacker, J.M. Intervention Effects of a School-Based Health Promotion Programme on Obesity Related Behavioural Outcomes. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, e476230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, A.; Willgoss, T.; Barbic, S.; International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) Mixed Methods Special Interest Group (SIG). Towards the use of mixed methods inquiry as best practice in health outcomes research. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, V.L.P.; Ivankova, N.V. Mixed Methods Research: A Guide to the Field, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Sheer, V.C.; Li, R. Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penţa, M.A.; Crăciun, I.C.; Băban, A. The power of anticipated regret: Predictors of HPV vaccination and seasonal influenza vaccination acceptability among young Romanians. Vaccine 2019, 38, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Crawford, J.; Rose, A.; Christiansen, P.; Cooke, R. Regret Me Not: Examining the Relationship between Alcohol Consumption and Regrettable Experiences. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Goot, M.J. Qualitative Research-Micro Lecture 5-Quality Criteria [Video File]. 2017. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfkeanmcvRc (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, R.L. A Practical Guide to Focus-Group Research. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Idea | Example Intervention Idea 1 | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Idea 1: Alcohol-post problem |  | Create awareness among young people that alcohol posts can be problematic, for example, by providing facts/figures (“research shows that seeing one alcoholpost increases the odds of drinking alcohol by 15%”). |

| Idea 2: (Too) many alcohol posts |  | Allow young people to come to an understanding that they post (too) many alcohol posts, for instance, by letting them scroll through their timelines and count the number of alcohol posts. |

| Idea 3: Warning alcohol posts |  | Provide an automatic warning when young people intend to upload an alcohol post (e.g., using machine learning to recognize alcohol in images automatically). For example, before uploading an alcohol post, they will get a message: “You are about to upload a post that includes alcohol. Are you sure that you want to upload this?” |

| Idea 4: Regret alcohol posts |  | Emphasize that young people could regret sharing alcohol posts the day after uploading the posts. |

| Idea 5: Perceived identity of alcoholposts |  | Point out to young people that alcohol posts are not well perceived (e.g., by parents and future employers). For example, show a resume including an alcohol post as a profile picture with the statement, “Is this how your future employer should perceive you?” |

| Idea 6: Correcting misperceived norms |  | Young people unfairly hold the idea that many young people drink too much, which could be reinforced by alcohol posts. This idea could be corrected by messages on social media, such as “Most young people consume 0 to 4 drinks when they go out.” |

| Idea 7: Alcohol posts are unrealistic |  | Show young people that alcohol posts are not an accurate representation of reality. These posts are often too positive and do not show the negative aspects of alcohol. For example, show a juxtaposition in which the first photo depicts “what you think happened” (laughing individuals with beers) and the second photo depicts “what actually happened after” (drunk individuals/vomiting). |

| Idea 8: Popular young people | 2 | Allow popular young people (e.g., good friends or influencers) to share social media messages that are negative about alcohol or emphasize not posting alcohol posts. |

| Ranking of Ideas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Mdn | |

| Idea 3 (warning alcohol posts) | 3.41 a | 2.18 | 3 |

| Idea 1 (alcohol-post problem) | 3.84 b | 2.16 | 4 |

| Idea 5 (perceived identity of alcohol posts) | 4.07 b | 2.14 | 4 |

| Idea 7 (alcohol post unrealistic) | 4.39 b | 2.31 | 5 |

| Idea 8 (popular young people) | 4.65 b | 2.34 | 5 |

| Idea 6 (correcting misperceptions) | 5.02 c | 2.14 | 5 |

| Idea 2 (too many alcohol posts) | 5.12 c | 2.18 | 5 |

| Idea 4 (regret alcohol posts) | 5.49 d | 2.13 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hendriks, H.; Thanh Le, T.; Gebhardt, W.A.; van den Putte, B.; Vanherle, R. Dealing with Alcohol-Related Posts on Social Media: Using a Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Young Peoples’ Problem Awareness and Evaluations of Intervention Ideas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105820

Hendriks H, Thanh Le T, Gebhardt WA, van den Putte B, Vanherle R. Dealing with Alcohol-Related Posts on Social Media: Using a Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Young Peoples’ Problem Awareness and Evaluations of Intervention Ideas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105820

Chicago/Turabian StyleHendriks, Hanneke, Tu Thanh Le, Winifred A. Gebhardt, Bas van den Putte, and Robyn Vanherle. 2023. "Dealing with Alcohol-Related Posts on Social Media: Using a Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Young Peoples’ Problem Awareness and Evaluations of Intervention Ideas" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105820

APA StyleHendriks, H., Thanh Le, T., Gebhardt, W. A., van den Putte, B., & Vanherle, R. (2023). Dealing with Alcohol-Related Posts on Social Media: Using a Mixed-Method Approach to Understand Young Peoples’ Problem Awareness and Evaluations of Intervention Ideas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105820