Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia Canada to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

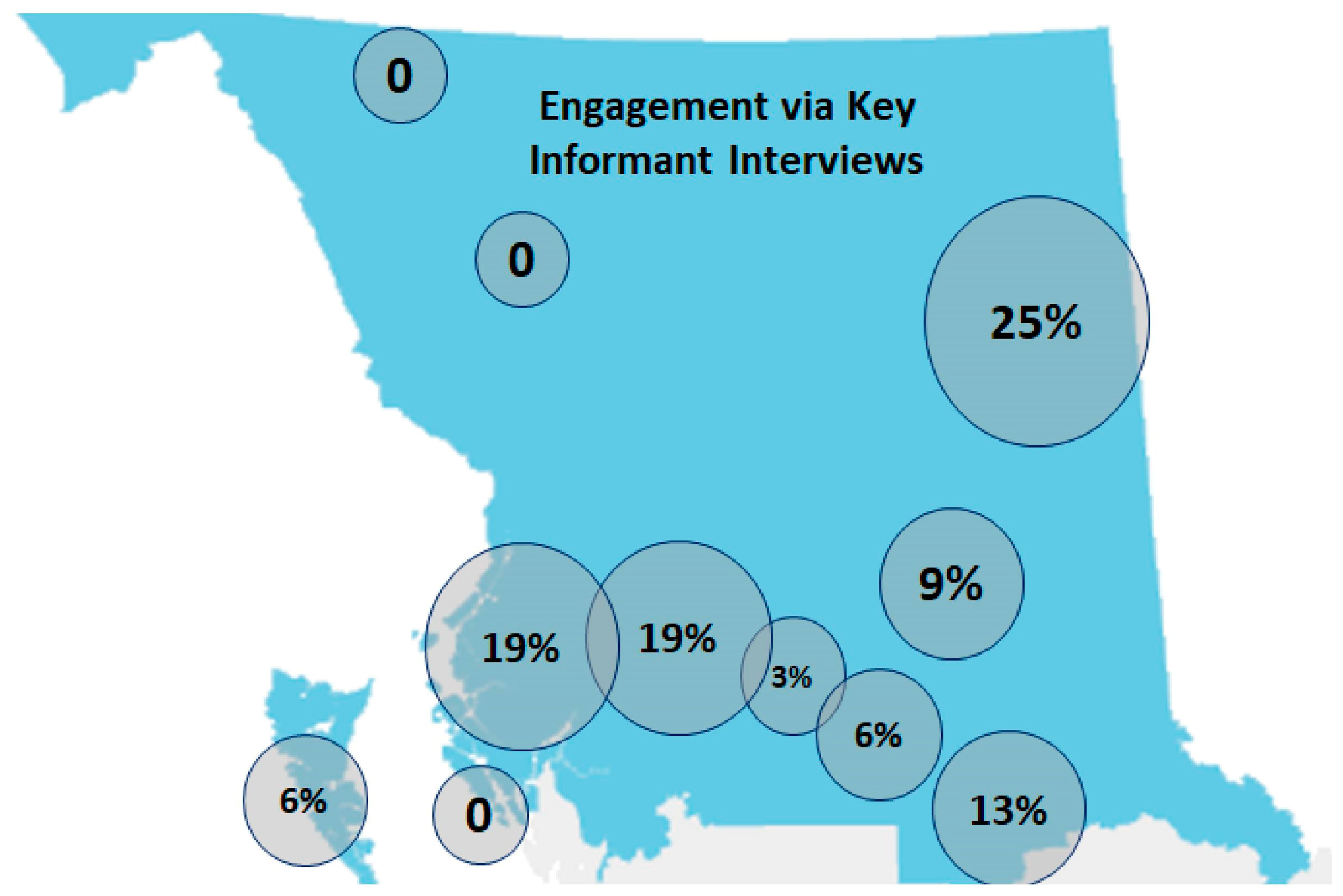

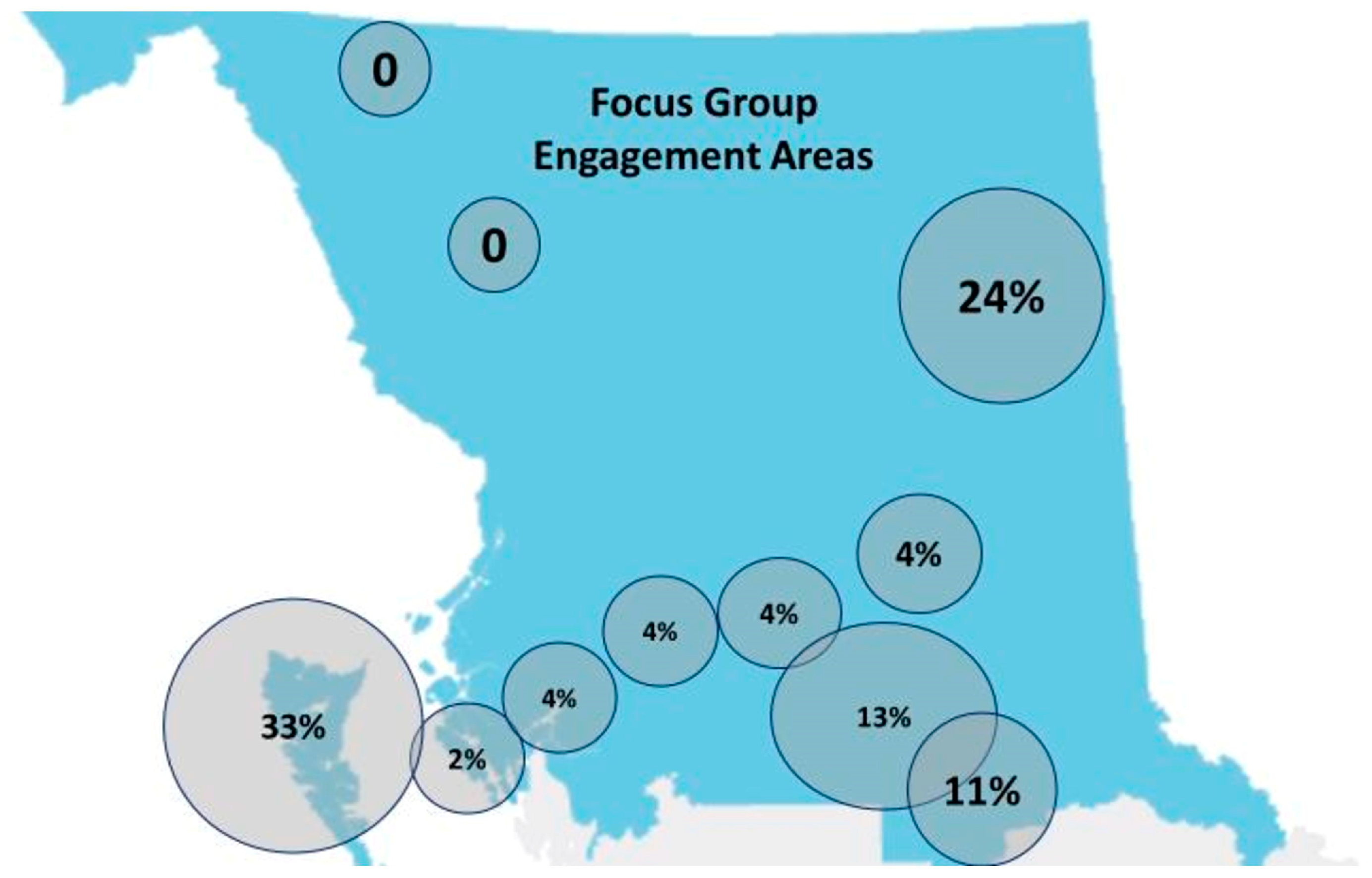

2.2. Research Setting and Participants

2.3. Community and Ethical Approvals

2.4. First Nations Governance

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Community Member Self-Rated Knowledge of Biobanking and Associated Genomic Research

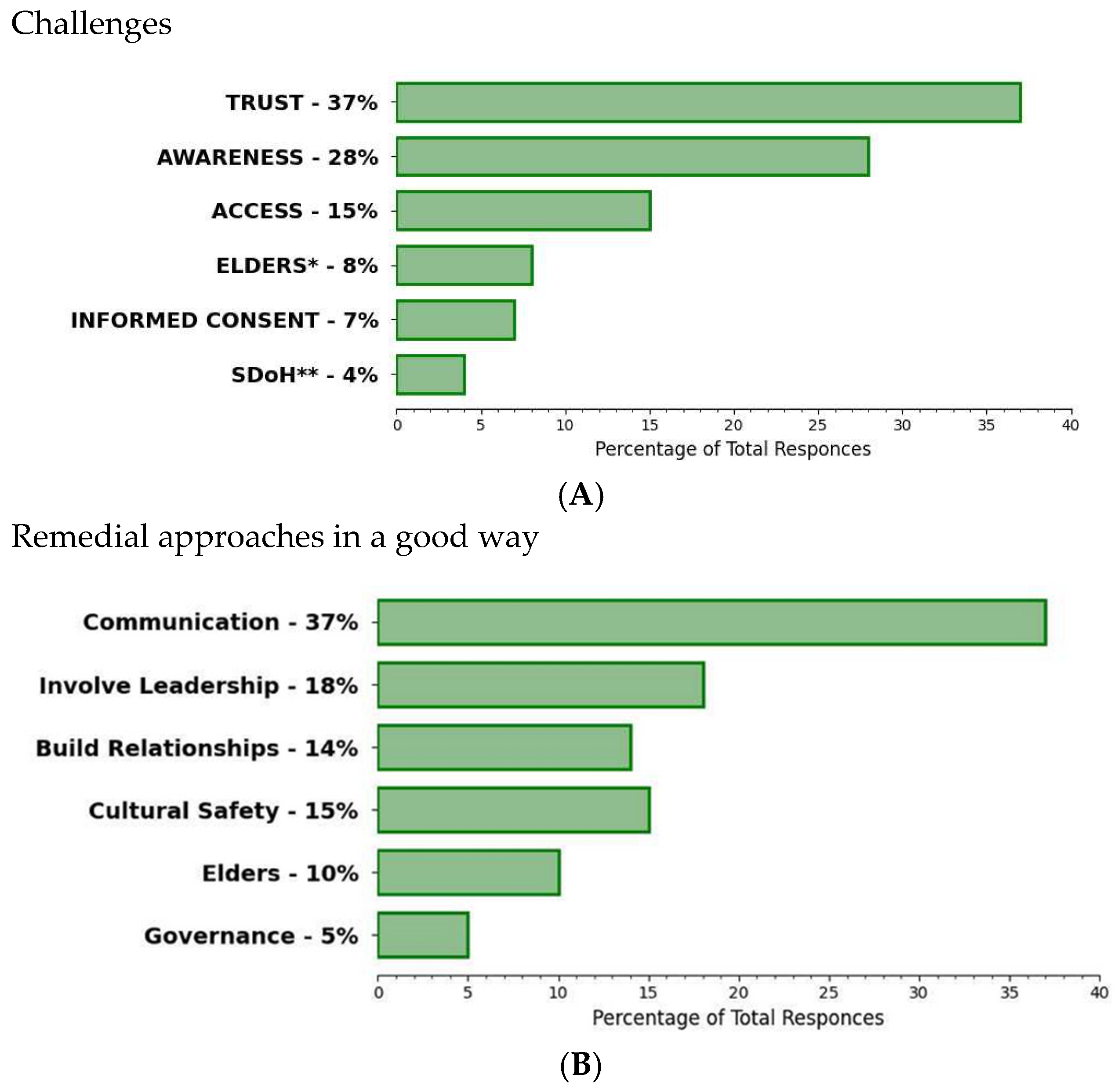

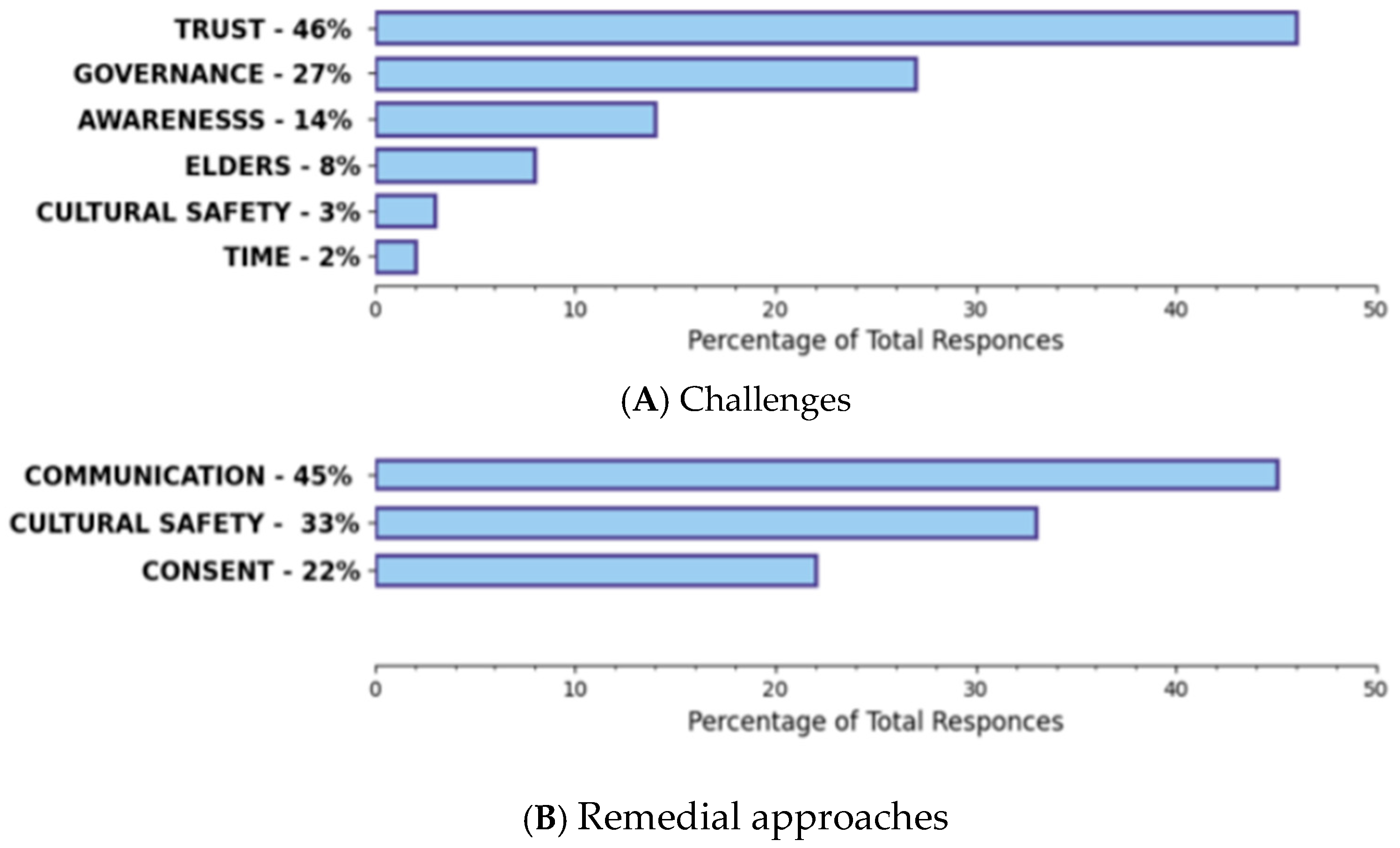

3.3. Response Frequencies for KIs and Community Members in FGs

Remedial Approaches in a Good Way

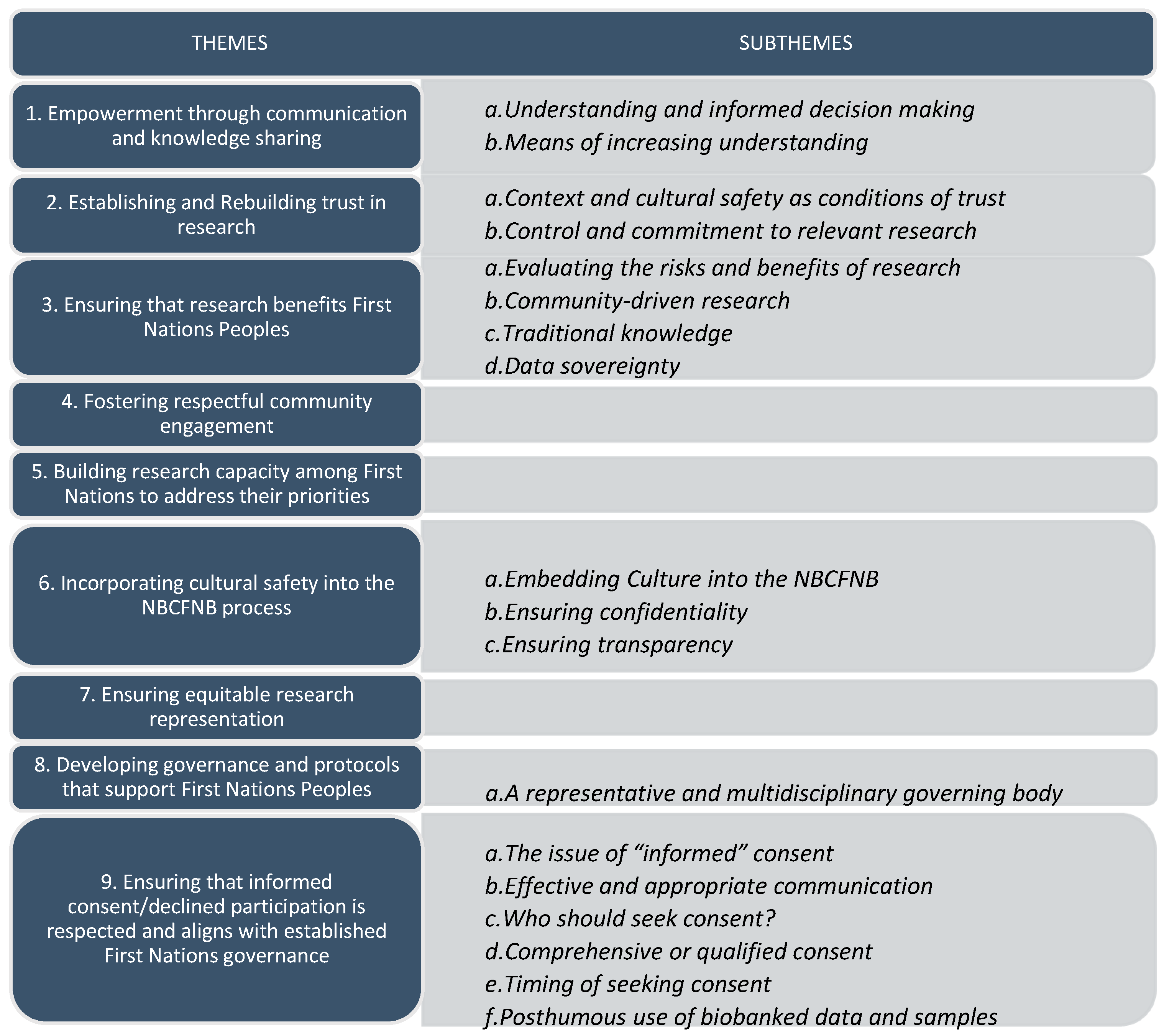

3.4. Qualitative Findings

- Empowerment through communication and knowledge sharing

- Understanding and informed decision making

And so, the process shouldn’t be just about the gold statement or business statement or mission statement, it needs to go back to the community where the people can interpret, allow them to interpret also what it means to them, what biobank means to them, and how it means to them as First Nations people.(FG4-P5)

The communication is really, really, key like we were talking about language, and just getting people to the point where they can see the benefits, right? But this isn’t something that happens in a year, we’re talking decades. Right, this is ongoing, it’s transforming, it’s growing. But I think that there’s much to be gained from this.(FG2-P3)

- b

- Means of increasing understanding

Creating champions within the community and having contact people within the community that have the proper information of the benefits and the risks of this. Just sharing that information within the community, having information sessions, really having a promotion campaign about it.And incorporating traditional ways of gathering and how we share our information within each community, identifying what’s unique for each community, and the biggest thing is sharing the information.(FG5-P4)

… it’s key that they are informed, very well informed. You would need to have a translator to speak to what the work that you are doing in the language because ‘what do you mean by DNA? What do you mean by northern biobank? You know, exactly what does that mean?’ And that needs to be interpreted for them. And not just the elderly but also to the to the younger generation next becausenot everybody’s well-versed in this biobank, well actually nobody is.(FG4-P5)

Go to assemblies or any gathering, health gathering, or even go to the band council meetings of each community and have a presentation and booklets, it’s good to have a presentation but leave some information behind… and I think one of the things that you know young people…they are good with computers. If we do have a website certainly have that available.(K106)

I really appreciated that video [that was] played at the information session…a lot of people may not be able to grasp that [referring to biobanking] just by talking to somebody. A lot of people are visual learners so if there’s something that’s already out there that kind of explains that. It might help. And then also having, well it would differ from nation to nation, having it explained in our language.(K128)

Social media works but it’s a touchy subject because we get worried about outsiders knowing.(FG7-P2)

Because in First Nations culture, they don’t rush. Things are not rushed. The pace is very different. So I really think this work is really important and I think if the community can understand what the goal is…I think they’re really going to want to volunteer to do and promote this research.(K123)

- 2

- Establishing and Rebuilding trust in research

- Context and cultural safety as conditions of trust

I think other benefits is to ensure that it is culturally safe and to ensure that it’s done in a way that our people can be proud of and feel safe to participate in. And that there is a cultural and traditional aspect to the entire project. I think the only risk or even apprehension that I can foresee is that First Nations people were heavily researched. And not with consent. Especially during residential school, the numerous experiments that were done on our children. And so it could hit a nerve in some communities. So, that’s why I feel it’s very important that it [the biobank] is rolled out in a very respectful and culturally safe way.(FG1-P3)

The whole way that community or the clients that you might encounter or people that you wanna have participate in this research, the trust factor is huge, because of the trauma response that people seem to have. Avoidance is, really deep, right?(KI23)

- b

- Control and commitment to relevant research

I’m on the fence on this whole thing. Becausethere’s always new ideas coming along and there’s always people coming to consult with us, First Nations, and on behalf of us kind of thing… I’m not questioning the integrity of your program, it’s just general…we’ve heard it a million times before, right, not just from you guys but every oil company, every government, saying the same old kinda thing, right?(FG3-P4)

- 3

- Ensuring that research benefits First Nations Peoples

- Evaluating the risks and benefits of research

The best communication for this is to have regular community meetings to explain exactly what biobanking is, and what’s the benefit, and if you’re gonna… Like, I’ve heard you say that it’s gonna be focused on cancer. Okay, then, you have the experts that are doing this … Even if it’s the final product to make the community more aware of what it is, what it entails, and how it’s gonna benefit our community, and to ensure the community understand that this is not a cure, it’s more information, and hopefully, a potential option that may arise is that it could lead to maybe intervention, prevention.(KI26)

So, you see that, whenever you are talking to the traditional healers and so on, they are very guarded because they do not want to give away their knowledge of plant medicine, which some corporate entity from far behind pulling the strings will be able to determine and go and take and make use of it without anything coming back to them.(KI22)

- b

- Community-driven research

I think it’s extremely important with the amount of industry and natural resources, especially up here in the north. There’s a lot of industries that are coming in and it’s, I think there’s a lot of effects on the natural and traditional foods and the impact, although there’s not a whole heck of a lot we can do about it, but at least having that information that there is an impact. And I’m astonished at the amount of cancer rates in the XXX [named community]. It seems like they’re exploding exponentially, so having a biobank would be really important to see if there’s some linkages or some risk factors or something that we’re missing that we could actually start addressing for future generations.(K120)

- c

- Traditional knowledge

The other piece I wanted to add too that we do need to have somebody with traditionalhealing or traditional practices. ‘Cause sometimes with those samples there may be a ceremony, there may be taboo, there may be something around samples and body samples, so just recognizing that there may be traditional things that have to happen for those processes.(KI20)

I’m wondering if there should be some form of ritual added in, whether if it’s a giving of tobacco for taking the sample or whether it’s outside or a prayer or a sage… just an honoring of the spirit of what it’s going to…(KI14)

I know that there’s a lot of spiritual reasoning behind people not wanting sampling done or that sort of thing, you know, any tissue samples taken for that purpose. So find a way to, a practice or something, go to the Chiefs maybe, and see what their suggestions are, or any First Nations leaders within the community.(KI09)

And the bank…that’s a lot of information that can end up being used in so many great ways. And like I said before with our natural medicines, because there is no research, if somebody chooses, you know, ‘Well, hey, I’m not going to go with this chemotherapy or I’m not going to go with this, I’m gonna, you know…’ then we have something that’s going to be for future that’s like, ‘Yeah, our medicines do work.’ Then you got that side, for, ‘Uh-ho! All our medicines work!’(FG2-P6)

Yeah are we curing cancer, or you know if, are we gonna create something, are we gonna go into traditional medicine?(FG2-P5)

I would suggest when that tissue is taken, ask whether there is natural medicine used or not. And what was actually being used, because that could actually alter the samples. Like was soap berries used, was spruce used, was chaga used? Which isn’t a normal question either. But some of them may have used it and maybe it’s altered it or shrunk it, that would all be viable information because looking at some of the traditional, did it affect that cancer? Has it changed it, did it shrink it, is it an aggressive cancer that didn’t actually kill because it was treated properly?(KI14)

- d

- Data sovereignty

Well, the more information that we have you know, the better the chances, but also we just have to be careful because this information can be used by some, some ways that other people may use it as monetary gain or whatever or other ways that can benefit others. Not in a way we are thinking of. But mainly I think it’s important the more information we have the better.(KI06)

- 4

- Fostering respectful community engagement

I think what you’re building here by coming to us, explaining it the way you are brings in the trust for me. I don’t know how everybody else feels but I think that’s huge for us. We’ve had so many other things done to us and so thatwe don’t trust too many people. But I feel the trust coming in by you explaining it so nicely and talking to us so we understand what you’re talking about.(FG6-P2)

When we normally do our information sharing to communities, if we do it the Western way, we’d be lucky if we get half a dozen to a dozen people in attendance, but if we do our within our culture, which is the feasts, some people call it the potlatch, we’ll get anywhere from 75 to 250 people.(FG4-P2)

If you could give us a questionnaire paper, you could bring to the [reserve], and just straight-out basic questions and then we could go around and do a survey to the Elders and those people in general and see what kind of feedback we get. And just see how they feel about it.(FG5-P1)

- 5

- Building research capacity among First Nations to address their priorities

I feel that it’s important for us to research that and have control over it ourselves, so we know it’s being taken care of sacredly. Each one of us have a spirit and a soul. And for mine to be out there is a big risk to allow people to research me for whatever reason there is. But I also feel it’s important the name attached to it, and I pray that this doesn’t break down in the future. Because it’s so important to have this. For my generations to come.(FG7-P3)

If we had more First Nations people actual in the, the process. I mean I think it’s a good idea generally, but just in a First Nations context, because we’ve been just [wrung] with the coals how many times right? And someone’s coming in and is like ‘oh we’re gonna help you’ and then, you know, then they get what they want and then they’re out of here.(FG3-P4)

It would be interesting to see too the transition of information between First Nations people and the medical professionals because right now it’s the family physicians that are in charge of our files. They know everything about us. … And so, when we meet with them, we talk about the database, that it would be good for us and a big question is ‘are they prepared to share that information with us? Are they open to us having access to their data?’(FG4-P5)

- 6

- Incorporating cultural safety into the NBCFNB process

- Embedding Culture into the NBCFNB

But you know, there’s a personal touch there, I think, I believe that makes that… says that, ‘Okay, um, it’s not so clinical,’ and I think if you’re going to have something set up for First Nations to come into, you know for a lab that’s traditionally Western, that would be really, really, clinical for a First Nations person.(FG4-P2)

That might be where a traditional healer comes in too, to make a little ceremony to make it safe.(FG6-P10)

…a lot of our people say that they don’t really understand the jargon of the professionals whether they be health or legal and so they like to narrow down the information and make it simple terms andnot too overwhelming, so I think it’s important to work with the staff andmake sure that they have a real understanding of it and then using them togenerate that information and flow it into the community.(KI19)

- b

- Ensuring confidentiality

the end result […] there’s gonna be a paper that’s produced and it’s gonna have these First Nation community names on there […] And long-term it might not be a good outcome because the stigma that comes...obviously that’s gonna have some kind of impact socially between First Nations communities. I think that’s something that you might want to consider […] Cause your pool is not very big.(KI05)

- c

- Ensuring transparency

I have a grandson, now. I don’t want that for him. So those things are all things that First Nations people have fears about too. Because, what will happen to the data? Can we trust people to do what they’re going to say to do, because we have this background where people didn’t do what they said they were going to do. Or they did things that were plainly unethical. You know, in the guise of science.(KI24)

Yeah, and if there’s misinformation given, you can give that fear mongering, especially based on our history of people saddling us from the time. And sure, I have, I remember the doctors just doing really random crazy things and going ‘What did they do?’ … You know, so makes you question, so then I think there are always underlying factors of what information you have to give and what, how useful a biobank is for our people.(KI03)

It’s distinct in thatthe board is somewhat overseeing and has that sense of responsibility regarding how this unfolds, or, operates and, however, in terms of the actual day to day in the operations and what occurs with the biobank, the board would not have direct contact with that.(KI21)

- 7

- Ensuring equitable research representation

…there’s limited access, limited travel, you know, now that they’ve shut down the Greyhound bus (Greyhound is a public bus company no longer serving northern BC). We have that Northern bus and the Northern Health bus [provided by NH] but you know it’s hard to schedule things around those kinds of things, we have the trains but I think reliable transportation is a big piece.(KI25)

So they don’t realize just how far people have to travel to go to get the help they need…Those are things that are really difficult for families. And when you get down there, having a place to stay. So economics, travel, isolation, lack of consultation.(KI17)

- 8

- Developing governance and protocols that support First Nations Peoples

- A representative and multidisciplinary governing body

So they’re also sharing what they’re learning with the communities so there’s less misunderstanding about stuff. So the more you bring in your cultural advisors, or just your Elder advisors that would play a huge role in opening it up to community. To see how what this works like, and how it, you know, and they can also guide you in that process in terms of cultural practices and cultural protocols.(KI08)

The way that our Chiefs have organized themselves is there’s an appointed leader who consults with the rest of the chiefs of the Northwest sub-region and that’s our political rep for the Northwest. Not a leader, but a rep and so there’s one for the Northwest, one for the North Central, one for the Northeast.(FG4-P1)

So really making sure that that whole ethics and all that access is developed more from a First Nations point of view rather than a colonial point of view.(KI20)

… you want someone who’s strong ethically, and like, community-wise and culturally, and we do have those people here, but how would you select? Like the North, even just the North is just huge. So do you wanta North Central person, a Northeast person, a Northwest person, or is it just one for the whole North? Good luck!(KI32)

You’ll be the role model for the other organizations in the area with regard to any health service providers out there… Blazing the trail, is what the biobank can do actually with communication pathways between organizations.(FG4-P2)

- 9

- Ensuring that informed consent/declined participation is respected and aligns with established First Nations governance

- The issue of “informed” consent

I know in our area, a lot of doctors and a lot of dentists, they tested on our people [without their consent], … that could be a possible barrier, but also having thatsuspicion of, ‘What are you going to do with our DNA? What? Are you selling it or are you doing this…or whatever?’(KI03)

I remember an incident where someone was diagnosed and didn’t understand the diagnosis and thought they were gonna die, and so you now got everybody in their family worked up because they didn’t understand that it wasn’t a malignant tumour, that they could have it removed and all of the process but they didn’t understand, they just heard cancer and everything else kind was muffled, so they just thought… ‘oh I’m gonna die,’ and started making plans for dying.(FG1-P3)

- b

- Effective and appropriate communication

I think that’s definitely something that, if somebody’s with a new initiative, any kind, that’s critical, but also continuing as you say that persistence, you have to maintain that conversation with Chiefs, Elders, and community members, and health leads, and so on.(KI09)

So I think it’s really important to have First Nations leaderships or people who are in a leadership position to get their consent.(KI05)

I would look at another avenue to take to get that consent…and I don’t necessarily think it has to be in the hospital setting.(FG4-P3)

When we take something from a tree we acknowledge that tree, when we take something from a fish we put the bones and that back in the water. There’s things that are done because you acknowledge what you’ve taken. So do you acknowledge what you’ve taken from a person or is that a gift? It’s, I think you have to have that conversation.(KI24)

- c

- Who should seek consent?

I would really advocate, that as the biobank develops how this communication, and how this informed consent is going to be sought, you probably are going to need more than one person, because of the geography. And they’re going to need to be spending time and they’re going to need to be visible, kind of on an ongoing basis.(KI23)

- d

- Comprehensive or qualified consent

That just because you give consent once, doesn’t mean that it’s a free for all and everybody gets to access it.(KI20)

For me, one consent form doesn’t mean for everything, you know. I think every time there’s someone coming into the bank with their research, I want them to give me another consent form, you know, for anything and everything.(FG7-P1)

It should spell out in the agreement with their donor [biobank participant] if he or she chooses to keep the sample in the biobank, it should say somewhat what they can do with it—they can say that do whatever you want with it or here’s specific things that you shouldn’t do. Give the authority to my daughter, son or whoever after.(KI06)

- e

- Timing of seeking consent

That one thing that our people really need to know is that they’re involved. If they’re not involved with any process of it then there is lack of interest in it. So if there’s a role that our leadership can play with any of the work that needs to take place in terms of advisory committee, then there’s more interest in it. ike with some community functions that I do, the hereditary chiefs are who we get involved becausewe operate through a cultural system.(KI08)

I would say I would do at least one to two engagements about the project before you even sought consent […] Try to build the relationship and, and the word, get the messaging out as early as possible before you’re sort of going after the signature. Because that in of itself for some people is not something they want to do lightly.(KI23)

… when you get a diagnosis of cancer, you don’t hear anything else. You don’t understand, half the time people don’t understand what’s being said. So when you present that consent, at that time or when you’re doing the initial surgery, you’re taking advantage of a vulnerable person.(KI24)

- f

- Posthumous use of biobanked data and samples

And then a few people around this area have come up and said ‘hey, our protocols are’—and the body being whole was actually specifically one of the ones mentioned to us, yeah, so that’s been really good.(KI09)

4. Discussion

4.1. Establishing and/or Rebuilding Trust in Research

4.2. Building Research Capacity among First Nations to Address Their Priorities

4.3. Developing Governance and Protocols That Support First Nations Peoples

4.4. Ensuring That Consent Is Appropriately Managed

4.5. Limitations

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coppola, L.; Cianflone, A.; Grimaldi, A.M.; Incoronato, M.; Bevilacqua, P.; Messina, F.; Baselice, S.; Soricelli, A.; Mirabelli, P.; Salvatore, M. Biobanking in health care: Evolution and future directions. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, N.R.; Chongo, M.; Hudson, M.; Arbour, L.; Wasserman, W.W.; Robertson, S.; Correard, S.; Wilcox, P. Indigenous Genomic Databases: Pragmatic Considerations and Cultural Contexts. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, N.R.; Boswell, B.T.; Deineko, V.; Hunt, M.A. Partnering With Northern British Columbia First Nations in the Spectrum of Biobanking and Genomic Research: Moving Beyond the Disparities. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genome, B.C. Canadian Patients to Benefit from Major Investment in Genomics and Precision Health Research. Genome British Columbia. 2018. Available online: https://www.genomebc.ca/canadian-patients-benefit-major-investment-genomics-precision-health-research/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Sagner, M.; McNeil, A.; Puska, P.; Auffray, C.; Price, N.D.; Hood, L.; Lavie, C.J.; Han, Z.G.; Chen, Z.; Brahmachari, S.K.; et al. The P4 Health Spectrum—A Predictive, Preventive, Personalized and Participatory Continuum for Promoting Healthspan. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 59, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provincial Health Services Authority. 2021. Available online: https://www.culturallyconnected.ca/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- BC Cancer. Spiritual Health: Supporting Person-Centred Care. 2019. Available online: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/coping-and-support-site/Documents/BCCancer_SpiritualHealth_Brochure.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Blackstock, C. Revisiting the Breath of Life Theory. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 49, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrin, J.J.; Betsou, F. Trends in Biobanking: A Bibliometric Overview. Biopreservation Biobanking 2016, 14, 65–74. Available online: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/epub/10.1089/bio.2015.0019 (accessed on 31 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- McDermott, U.; Downing, J.R.; Stratton, M.R. Genomics and the Continuum of Cancer Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, A.A.; Carini, C. Are innovation and new technologies in precision medicine paving a new era in patients centric care? J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson-Grosjean, J.; Caron, N. Bottlenecks in Translating Genomics from the Academy into the Real World: Risk, Trust and Communication. 2012. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/22226410/Bottlenecks_in_translating_genomics_from_the_academy_into_the_real_world_risk_trust_and_communication (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Biobank Research Center (UBC Office of Biobank Education and Research and the Canadian Tissue Repository Network). Available online: https://biobanking.org/locator (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Bustamante, C.D.; De La Vega, F.M.; Burchard, E.G. Genomics for the world. Nature 2011, 475, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popejoy, A.B.; Fullerton, S.M. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature 2016, 538, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, G. Facing up to injustice in genome science. Nature 2019, 568, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Human Genomics in Global Health: Genomics and the Global Health Divide. World Health Organization. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/genomics/healthdivide/en/ (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Charles, E.J.; Kron, I.L. Bedside-to-Bench and Back Again: Surgeon-Initiated Translational Research. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 105, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, C.A.M.; Cook, C. Creating conditions for Canadian aboriginal health equity: The promise of healthy public policy. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, N.A.; Hudson, M.; Ballantyne, L.L.; Garba, I.; Martinez, A.; Taualii, M.; Arbour, L.; Caron, N.R.; Rainie, S.C. Genomic Research Through an Indigenous Lens: Understanding the Expectations. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2019, 20, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K.A.; Muller, C.; Noonan, C.; Booth-LaForce, C.; Buchwald, D.S. Increasing health equity through biospecimen research: Identification of factors that influence willingness of Native Americans to donate biospecimens. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 21, 101311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, M.; Wolf, L. The Havasupai Indian Tribe Case—Lessons for Research Involving Stored Biologic Samples. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, J. Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP): Impact on indigenous communities. In Living with the Genome; Clarke, A., Ticehurst, F., Eds.; Ethical and Social Aspects of Human Genetics; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Aramoana, J.; Koea, J.; CommNETS Collaboration. An Integrative Review of the Barriers to Indigenous Peoples Participation in Biobanking and Genomic Research. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGahan Linn, K.; Guno, P.; Johnson, H.; Coldman, A.J.; Spinelli, J.J.; Caron, N.R. Cancer in First Nations people living in British Columbia, Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2017, 28, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Nations Health Authority. Indigenous Health Improves But Health Status Gap With Other British Columbians Widens. December 2018. Available online: https://www.fnha.ca/about/news-and-events/news/indigenous-health-improves-but-health-status-gap-with-other-british-columbians-widens (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Rasali, D.; Zhang, R.; Guram, K.; Gustin, S.; Hay, D.I. Priority Health Equity Indicators for British Columbia: Selected Indicators Report. Provincial Health Services Authority. 2016. Available online: http://www.bccdc.ca/pop-public-health/Documents/Priority%20health%20equity%20indicators%20for%20BC_selected%20indicators%20report_2016.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Canadian Partnership against Cancer. First Nations Cancer Control in Canada Baseline Report. Toronto, ON. 2013. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/first-nations-cancer-control-baseline-report.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Lavoie, J.G.; Kaufert, J.; Browne, A.J.; O’Neil, J.D. Managing Matajoosh: Determinants of first Nations’ cancer care decisions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Strengthening Indigenous Research Capacity. Setting New Directions to Support Indigenous Research and Research Training in Canada-Strategic Plan 2019–2022. 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/crcc-ccrc/documents/strategic-plan-2019-2022/sirc_strategic_plan-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH). Fact Sheet-Access to Health Services as a Social Determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/determinants/FS-AccessHealthServicesSDOH-2019-EN.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Nguyen, N.H.; Subhan, F.B.; Williams, K.; Chan, C.B. Barriers and Mitigating Strategies to Healthcare Access in Indigenous Communities of Canada: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, N.; Elder Adam, W.N.; Chongo, M.; Howard Patricia Deineko, V.; Hunt, M.A. The Northern First Nations Biobank: Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research. 11 February 2021; University of British Columbia. Available online: https://learningcircle.ubc.ca/2020/12/18/the-northern-first-nations-biobank-211/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Arbour, L.; Morrison, J.; McIntosh, S.; Whittome, B.; Polanco, F.; Rupps, R. Abstracts from the 16th International Congress on Circumpolar Health: Ten years of a community based participatory research program to address the high rate of Long QT syndrome in First Nations of northern BC. Int. J. Circumpolar. Health 2016, 75, 33200. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Health Authority, 2020. Regions. Northern. First Nations Population in the North. Available online: https://www.fnha.ca/about/regions/north (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Northern Health, about Us, Quick Facts. Available online: https://www.northernhealth.ca/about-us/quick-facts (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- First Nations Health Authority. Northern Region TOR. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjx_a7N9_L8AhWhm4kEHR0pDsYQFnoECAgQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fnha.ca%2FDocuments%2FFNHA-Northern-Region-TOR.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3A3L-qDWwafFgxbwO1e79b (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- First Nations Health Authority. FNHA Overview. 2021. Available online: https://www.fnha.ca/about/fnha-overview (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Version 11). 2015. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Peat, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Smith, J. Interpretive phenomenological analysis applied to healthcare research. Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M. Perfect subjects: Race tuberculosis and the Qu’Appelle BCG vaccine Trial. Can. Bull. Med. Hist. 1998, 15, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosby, I. Administering colonial science: Nutrition research and human biomedical experimentation in Aboriginal communities and residential schools. Hist. Soc./Soc. Hist. 2013, 46, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. The First Nations Principles of OCAP®. 2021. Available online: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Caron, N.; Boswell, B.T.; Deineko, V.; Hunt, M.A.; Cross, N.; Arbour, L. The Northern Biobank Initiative: Dialogue to Permit Dialogue Lessons Learned in Establishing a First Nations Biobank. 16 October 2017; Paetzold Auditorium, Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, BC. Available online: https://med-fom-surgery.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2017/10/Chung-Day-Program-2017.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Brody, J.L.; Dalen, J.; Annett, R.D.; Scherer, D.G.; Turner, C.W. Conceptualizing the Role of Research Literacy in Advancing Societal Health. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claw, K.G.; Anderson, M.Z.; Begay, R.L.; Tsosie, K.S.; Fox, K.; Garrison, N.A.; Summer internship for Indigenous peoples in Genomics (SING) Consortium. A framework for enhancing ethical genomic research with Indigenous communities. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, R.; Heaney, K. We can wipe an entire culture”: Fears and promises of DNA biobanking among Native Americans. Dialect Anthropol. 2015, 39, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, A.; Hudson, M.; Milne, M.; Port, R.V.; Russell, K.; Smith, B.; Toki, V.; Uerata, L.; Wilcox, P.; Bartholomew, K.; et al. Engaging Māori in biobanking and genomic research: A model for biobanks to guide culturally informed governance, operational, and community engagement activities. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.; Tsosie, R.; Sahota, P.; Parker, M.; Dillard, D.; Sylvester, I.; Lewis, J.; Klejka, J.; Muzquiz, L.; Olsen, P.; et al. Exploring pathways to trust: A tribal perspective on data sharing. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, E.; Radin, J. Indigenous biospecimen collections and the cryopolitics of frozen life. J. Sociol. 2015, 51, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Coe, R.R.; Lesueur, R.; Kenny, R.; Price, R.; Makela, N.; Birch, P.H. Indigenous Peoples and genomics: Starting a conversation. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson Cr Rourke, J.; Oandasan, I.; Bosco, C. Progress made on access to rural healthcare in Canada. Can. J. Rural. Med. 2020, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.R.; Rodriguez-Lonebear, D.; Martinez, A. Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations. Data Sci. J. 2019, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, A.; Smith, B.; Toki, V.; Southey, K.; Hudson, M. Engaging Maori in Biobanking and Genetic Research: Legal, Ethical, and Policy Challenges. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2015, 6. Available online: https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/view/7464 (accessed on 31 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kirby, E.; Tassé, A.M.; Zawati, M.; Knoppers, B.M. Data Access and Sharing by Researchers in Genomics. March 2018. Available online: https://www.genomequebec.com/DATA/PUBLICATION/35_en~v~Data_Access_and_Sharing_by_Researchers_in_Genomics_-_Policy_Brief.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Chennells, R.; Steenkamp, A. International Genomics Research Involving the San People. In Ethics Dumping; Schroeder, D., Cook, J., Hirsch, F., Fenet, S., Muthuswamy, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 15–22. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64731-9_3 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Ho, C. Rethinking Informed Consent in Biobanking and Biomedical Research: A Taiwanese Aboriginal Perspective and the Implementation of Group Consultation. ABR 2017, 9, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosseim, P.; Dove, E.S.; Baggaley, C.; Meslin, E.M.; Cate, F.H.; Kaye, J.; Harris, J.R.; Knoppers, B.M. Building a data sharing model for global genomic research. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.; Borry, P. “You want the right amount of oversight”: Interviews with data access committee members and experts on genomic data access. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, D.; Cook, J.; Hirsch, F.; Fenet, S.; Muthuswamy, V. (Eds.) Ethics Dumping: Case Studies from North-South Research Collaborations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64731-9 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Garrison, N.A.; Carroll, S.R.; Hudson, M. Entwined Processes: Rescripting Consent and Strengthening Governance in Genomics Research with Indigenous Communities. J. Law Med. Ethics 2020, 48, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellowknives Dene First Nation Wellness Division; Lines, L.-A.; Jardine, C.G. Connection to the land as a youth-identified social determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembly of First Nations. Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery. January 2018. Available online: https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/18-01-22-Dismantling-the-Doctrine-of-Discovery-EN.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Williams, E.; Guenther, J.; Arnott, A. Traditional Healing: A Literature Review. 2011. Available online: http://www.covaluator.net/docs/S2.2_traditional_healing_lit_review.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Couzin-Frankel, J. Researchers to Return Blood Samples to the Yanomamo. Science 2010, 328, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbour, L.; Cook, D. DNA on Loan: Issues to Consider when Carrying Out Genetic Research with Aboriginal Families and Communities. Public Health Genom. 2006, 9, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Columbia: Building relationships with Indigenous peoples, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (Declaration Act). 2022. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/indigenous-people/new-relationship/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Government of Canada, Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Bill C-15: What We Learned Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/wwl-cna/c15/index.html (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Karpen, S.C. The Social Psychology of Biased Self-Assessment. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T. “We’re Over-Researched Here!”: Exploring Accounts of Research Fatigue within Qualitative Research Engagements. Sociology 2008, 42, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, M.J. Ethical, legal and social issues of biobanking: Past, present, and future. Biopreserv. Biobanking 2017, 15, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaradzki, J. Geneticization and biobanking. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 1, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, T.; Murdoch, B. Genes, cells, and biobanks: Yes, there’s still a consent problem. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2002654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stages | Initiation | Planning | Implementation and Execution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phases | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phase IV | Phase V | Phase VI |

| Deliverable | - Business plan - Establish collaborations - Connect with the Canadian Tissue Repository Network (CTRNet) - Preliminary consultations | REB Approvals:

Sustainability plan | Prospective sample collection (breast, colon, thyroid, and melanoma cancers) | Fresh tissue sample collection | Integration of other tumour types to Northern Biobank Initiative (NBI) | Expansion of sample collection throughout the Northern Health Authority (NHA) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caron, N.R.; Adam, W.; Anderson, K.; Boswell, B.T.; Chongo, M.; Deineko, V.; Dick, A.; Hall, S.E.; Hatcher, J.T.; Howard, P.; et al. Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia Canada to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105783

Caron NR, Adam W, Anderson K, Boswell BT, Chongo M, Deineko V, Dick A, Hall SE, Hatcher JT, Howard P, et al. Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia Canada to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105783

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaron, Nadine R., Wilf Adam, Kate Anderson, Brooke T. Boswell, Meck Chongo, Viktor Deineko, Alexanne Dick, Shannon E. Hall, Jessica T. Hatcher, Patricia Howard, and et al. 2023. "Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia Canada to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105783

APA StyleCaron, N. R., Adam, W., Anderson, K., Boswell, B. T., Chongo, M., Deineko, V., Dick, A., Hall, S. E., Hatcher, J. T., Howard, P., Hunt, M., Linn, K., & O’Neill, A. (2023). Partnering with First Nations in Northern British Columbia Canada to Reduce Inequity in Access to Genomic Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105783