Athletes and Coaches through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative View of Goal Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Philosophical Assumptions

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure and Materials

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Quality Criteria

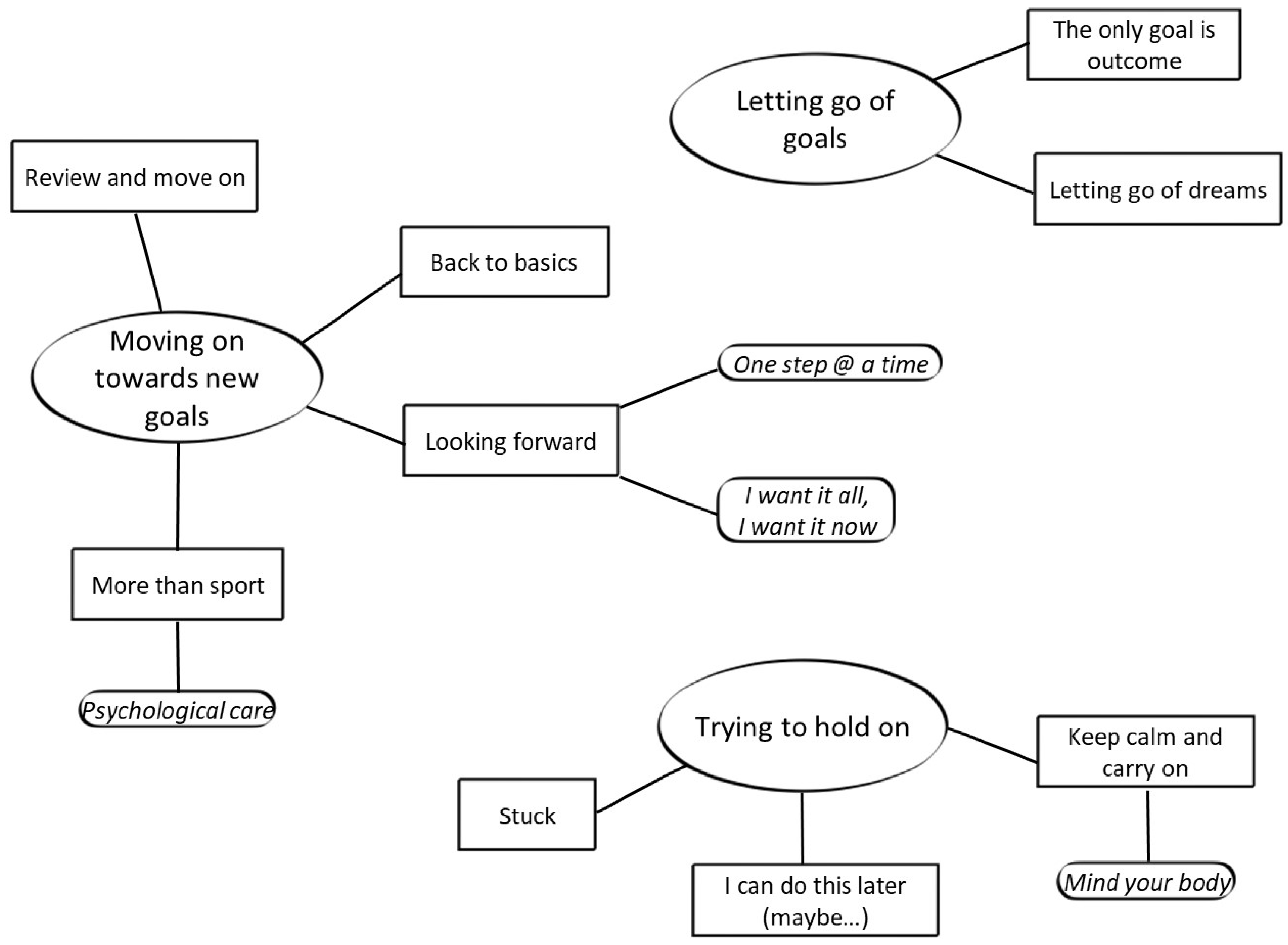

3. Results

3.1. Moving on towards New Goals

3.1.1. Review and Move On

3.1.2. Back to Basics

3.1.3. Looking Forward

One Step @ a Time

I Want It All, I Want It Now

3.1.4. More Than Sport

Psychological Care

3.2. Letting Go of Goals

3.2.1. Letting Go of Dreams

3.2.2. The Only Goal Is Outcome

3.3. Trying to Hold On

3.3.1. Keep Calm and Carry On

Mind Your Body

3.3.2. I Can Do This Later (Maybe…)

3.3.3. Stuck

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doran, G.T. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives. Manag. Rev. 1981, 70, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, R.D.; Tenenbaum, G.; Galily, Y. The 2020 coronavirus pandemic as a change-event in sport performers’ careers: Conceptual and applied practice considerations. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/report-of-the-who-china-joint-mission-on-coronavirus-disease-2019 (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Lesser, I.A.; Nienhuis, C.P. The Impact of COVID-19 on physical activity behavior and well-being of Canadians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, G.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Battaglia, G.; Pippi, R.; D’Agata, V.; Palma, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Musumesi, G. The impact of physical activity on psychological health during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinke, R.J.; Papaioannou, A.; Henriksen, K.; Si, G.; Zhang, L.; Haberl, P. Sport psychology services to high performance athletes during COVID-19. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 18, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taku, K.; Arai, H. Impact of COVID-19 on athletes and coaches, and their values in Japan: Repercussions of postponing the Tokyo 2020 olympic and paralympic games. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Sedikides, C. Holding on to the goal or letting it go and moving on? A tripartite model of goal striving. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swann, C.; Rosenbaum, S. Do we need to reconsider best practice in goal setting for physical activity promotion? Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 52, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P. Goal setting. In Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology: Theories and Applications; Mugford, A., Cremades, J.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a theory by induction: The example of goal setting theory. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staufenbiel, K.; Lobinger, B.; Strauss, B. Home advantage in soccer—A matter of expectations, goal setting and tactical decisions of coaches? J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.; Weinberg, R.S.; Fernández-Castro, J.; Capdevila, L. Emotional and motivational mechanisms mediating the influence of goal setting on endurance athletes’ performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsblom, K.; Konttinen, N.; Weinberg, R.; Matilainen, P.; Lintunen, T. Perceived goal setting practices across a competitive season. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2019, 14, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.H.; Healy, L.C.; McEwan, D. The application of goal setting theory to goal setting interventions in sport: A systematic review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, L.C.; Ntoumanis, N.; van Zanten, J.J.C.S.V.; Paine, N. Goal striving and well-being in sport: The role of contextual and personal motivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascret, N. Confinement during COVID-19 outbreak modifies athletes’ self-based goals. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 51, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, N.; Atienza, F.L.; Tomás, I.; Duda, J.L.; Balaguer, I. The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Lockdown on Athletes’ Subjective Vitality: The Protective Role of Resilience and Autonomous Goal Motives. Front. Psychol. 2021, 10, 612825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, K.E.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Achievement goals and optimal motivation: Testing multiple goal models. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblinger-Peters, V.; Krenn, B. “Time for recovery” or “Utter uncertainty”? The postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic games through the eyes of olympic athletes and coaches. A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 610856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.; Werthner, P. Gathering narratives: Athletes’ experiences preparing for the Tokyo summer olympic games during a global pandemic. J. App. Sport Psychol. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGannon, K.R.; Smith, B.; Kendellen, K.; Gonsalves, C.A. Qualitative research in six sport and exercise psychology journals between 2010 and 2017: An updated and expanded review of trends and interpretations. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 19, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, R.D.; Tenenbaum, G. The role of change in athletes’ careers: A scheme of change for sport psychology practice. Sport Psychol. 2011, 25, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B.W.; Van Raalte, J.L.; Linder, D.E. Athletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel? Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1993, 24, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, S.; Santi, G.; di Fronso, S.; Montesano, C.; Di Gruttola, F.; Ciofi, E.G.; Morgilli, L.; Bertollo, M. Athletes and adversities: Athletic identity and emotional regulation in time of COVID-19. Sport Sci. Health 2020, 16, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McChesney, K.; Aldridge, J. Weaving an interpretivist stance throughout mixed methods research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2019, 42, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio, E. Narrating a crime: Contexts and accounts of deviant actions. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approach 2009, 3, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harré, R.; Moghaddam, F.M. The Self and Others. Positioning Individuals and Groups in Personal, Political, and Cultural Contexts; Praeger: West Port, CT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, C.; Moran, A.; Piggott, D. Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terry, G.; Braun, V. Short but often sweet: The surprising potential of qualitative survey methods. In Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques; Braun, V., Clarke, V., Gray, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Best, S.J.; Krueger, B.S. Internet survey design. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; Fielding, N., Lee, R.M., Blank, G., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Judging the quality of Qual. Inq.: Criteriology and relativism in action. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S. Rethinking ‘validity’ and ‘trustworthiness’ in Qual. Inq.: How might we judge the quality of qualitative research in sport and exercise sciences? In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; Caddick, N. Qualitative methods in sport: A concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia Pac. J. Sport Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, A.; Moesch, K.; Jönsson, C.; Kenttä, G. Potentially prolonged psychological distress from postponed Olympic and Paralympic games during COVID-19—Career uncertainty in elite athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, W.E.G.; Quartiroli, A.; Zakrajsek, R.; Eckenrod, M. Increasing collegiate strength and conditioning coaches’ communication of training performance and process goals with athletes. Streng. Cond. J. 2019, 41, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, L.C.; Tincknell-Smith, A.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Goal setting in sport and performance. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, R.; Butt, J. Goal-setting and sport performance. Research findings and practical applications. In Routledge Companion to Sport and Exercise Psychology: Goal Perspectives and Fundamental Concepts; Papaioannou, A.G., Hackfort, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wrosch, C.; Scheier, M.F.; Miller, G.E.; Schulz, R.; Carver, C.S. Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: Goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 97, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Wrosch, C.; Fleeson, W. Developmental regulation before and after a developmental deadline: The sample case of “biological clock” for childbearing. Psychol. Aging 2001, 16, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filby, W.C.D.; Maynard, I.W.; Graydon, J.K. The effect of multiple-goal strategies on performance outcomes in training and competition. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1999, 11, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D. Winning isn’t everything: Examining the impact of performance goals on collegiate swimmers’ cognitions and performance. Sport Psychol. 1989, 3, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, K.; Schinke, R.; Noce, F.; Poczwardowski, A.; Si, G. Working with athletes during a pandemic and social distancing: International Society of Sport Psychology Corona Challenges and Recommendations. Int. Soc. Sport Psychol. 2020. Available online: https://www.issponline.org/index.php/component/k2/item/49-issp-corona-challenges-and-recommendations (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Ruffault, A.; Fournier, J.F.; Bernier, M.; Hauw, N. Anxiety and motivation to return to sport during the French COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, R.S. Goal setting and performance in sport and exercise settings: A synthesis and critique. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Fronso, S.; Costa, S.; Montesano, C.; Di Gruttola, F.; Ciofi, E.G.; Morgilli, L.; Robazza, C.; Bertollo, M. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress and psychobiosocial states in Italian athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 20, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, G.; Quartiroli, A.; Costa, S.; di Fronso, S.; Montesano, C.; Di Gruttola, F.; Ciofi, E.G.; Morgilli, L.; Bertollo, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on Coaches’ Perception of Stress and Emotion Regulation Strategies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, L.; Janse van Rensburg, D.C.C.; Jansen van Rensburg, A.; Ramagole, D.A.; Holtzhausen, L.; Dijkstra, H.P. Nowhere to hide: The significant impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) measures on elite and semi-elite South African athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sports 2020, 23, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, M.; Forzini, F.; Biondi, S.; Di Liborio, M.; Vaccaro, M.G.; Georgiadis, E.; Conti, C. How does a sport psychological intervention help professional cyclists to cope with their mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 607152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.A.; Gustafsson, H.; Callow, N.; Woodman, T. Written emotional disclosure can promote athletes’ mental health and performance readiness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 599925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, O.A. Sport cyberpsychology in action during the COVID-19 pandemic (opportunities, challenges, and future possibilities): A narrative review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 621283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.; Carless, D. Life Story Research in Sport: Understanding the Experiences of Elite and Professional Athletes through Narrative; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Everard, C.; Wadey, R.; Howells, K. Storying sports injury experiences of elite track athletes: A narrative analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 56, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohsten, J.; Barker-Ruchti, N.; Lindgren, E.C. Caring as sustainable coaching in elite athletics: Benefits and challenges. Sports Coach Rev. 2020, 9, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, B. Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2018, 10, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, K.; Li, T.; Luo, D.; Hou, F.B.F.; Stratton, T.D.; Kavcic, V.; Jiao, R.; Xu, R.; Yan, S.; Jiang, Y. Psychological stress and gender differences during COVID-19 pandemic in Chinese population. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, C.M.; Harvey, S.; Hainline, B.; Hitchcock, M.E.; Reardon, C.L. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related mental disorders in elite athletes: A narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Cagno, A.; Buonsenso, A.; Baralla, F.; Grazioli, E.; Di Martino, G.; Lecce, E.; Calcagno, G.; Fiorilli, G. Psychological impact of the quarantine-induced stress during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak among Italian athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2020, 17, 8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, S.; De Gregorio, E.; Zurzolo, L.; Santi, G.; Ciofi, E.G.; Di Gruttola, F.; Morgilli, L.; Montesano, C.; Cavallerio, F.; Bertollo, M.; et al. Athletes and Coaches through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative View of Goal Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095085

Costa S, De Gregorio E, Zurzolo L, Santi G, Ciofi EG, Di Gruttola F, Morgilli L, Montesano C, Cavallerio F, Bertollo M, et al. Athletes and Coaches through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative View of Goal Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095085

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Sergio, Eugenio De Gregorio, Lisa Zurzolo, Giampaolo Santi, Edoardo Giorgio Ciofi, Francesco Di Gruttola, Luana Morgilli, Cristina Montesano, Francesca Cavallerio, Maurizio Bertollo, and et al. 2022. "Athletes and Coaches through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative View of Goal Management" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095085

APA StyleCosta, S., De Gregorio, E., Zurzolo, L., Santi, G., Ciofi, E. G., Di Gruttola, F., Morgilli, L., Montesano, C., Cavallerio, F., Bertollo, M., & di Fronso, S. (2022). Athletes and Coaches through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative View of Goal Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095085