Health Equity Implications of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Visitation Strategies in Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario: A Mixed Method Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objectives and Research Questions

- What are stakeholders’ perspectives on the priority, feasibility, and acceptability, as well as implementation considerations (duration, frequency, number of visitors), of different visitation strategies to LTC homes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario?

- What are the lived experiences of long-term care residents, their family members, and their designated caregivers of the COVID-19 lockdown and visitation strategies in the context of LTC homes in Ontario?

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.5.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.5.3. Integration and Interpretation

2.5.4. Researcher Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Stakeholder Perspectives on Visits to Long-Term Care Homes

“… we had our first grandchild … she hasn’t been able to hug them or hold them. And he’s going to be a year and a half … she hasn’t held him in over a year, or he hasn’t sat on her lap in over a year”.(Interview D)

“I didn’t only help my mom, I would help everybody else right, but I can’t do that now. So you’d lose some of that relationship, even helping other residents, even talking to other residents, you’re not allowed to. So, you really are there for your resident only, and the relationships with everybody else within the home is slightly different”.(Interview G)

“It [virtual visit] helps my parents, it helps us. It also helps us in different ways, not only in showing our love telling them, you know, our love, [but] showing the grandchildren who don’t want to sometimes be there”.(Interview B)

4. Discussion

The Equity Implications of Visitation Strategies for Long-Term Care Homes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G.; Merone, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of published research data on COVID-19 infection-fatality rates. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Eng. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Meyer, B.D.; Sullivan, J.X. Income and Poverty in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act. 2020, 2020, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, A.; Hoy, C.; Ortiz-Juarez, E. Estimates of the Impact of COVID-19 on Global Poverty; WIDER working paper 2020; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Singh, J. COVID-19 and its impact on society. Electron. Res. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 146, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Myint, M.T.; Zeanah, C.H. Increased Risk for Family Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. The Impact of COVID-19 on Global Health Goals. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-global-health-goals (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.Z.; Wang, S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsu, A.T.; Lane, N.; Sinha, S.K.; Dunning, J.; Dhuper, M.; Kahiel, Z.; Sveistrup, H. Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes–ongoing challenges and policy response. Int. Long-Term Care Policy Netw. 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Langins, M.; Curry, N.; Lorenz-Dant, K.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Rajan, S.; World Health Organization. The COVID-19 pandemic and long-term care: What can we learn from the first wave about how to protect care homes? Eurohealth 2020, 26, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Livelihoods, Their Health and Our Food Systems. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people’s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Perrotta, F.; Corbi, G.; Mazzeo, G.; Boccia, M.; Aronne, L.; D’Agnano, V.; Komici, K.; Mazzarella, G.; Parrella, R.; Bianco, A. COVID-19 and the elderly: Insights into pathogenesis and clinical decision-making. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Lana, S.; Marquié, M.; Ruiz, A.; Boada, M. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and effects on elderly individuals with dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 588772. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Herrera, A.; Zalakaín, J.; Lemmon, E.; Henderson, D.; Litwin, C.; Hsu, A.T.; Schmidt, A.E.; Kruse, G.A.F.; Fernández, J. Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: International evidence. In LTCcovid org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network; CPEC-LSE: London, UK, 2020; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Information (CIHI). Long-Term Care Homes in Canada: How Many and who Owns Them? Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/long-term-care-homes-in-canada-how-many-and-who-owns-them (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Ontario Long Term Care Association. This Is Long-Term Care. 2019. Available online: https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/TILTC2019web.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Government of Ontario. How Ontario is Responding to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/how-ontario-is-responding-covid-19 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Government of Ontario. Chief Medical Officer of Health Memo—COVID-19 Updates: Visitors. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/dir_mem_res.aspx (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Bethell, J.; O’Rourke, H.M.; Eagleson, H.; Gaetano, D.; Hykaway, W.; McAiney, C. Social Connection is Essential in Long-Term Care Homes: Considerations During COVID-19 and Beyond. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, A. Neglected No More: The Urgent Need to Improve the Lives of Canada’s Elders in the Wake of a Pandemic; Random House of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patient Ombudsman. Honouring the Voices and Experiences of Long-Term Care Home Residents, Caregivers and Staff during the First Wave of COVID-19 in Ontario. Available online: https://www.patientombudsman.ca/Portals/0/documents/covid-19-report-en.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Government of Ontario. Update to Visits at Long-Term Care Homes. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ltc/docs/covid-19/mltc_resuming_ltc_home_visits_20200715.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Government of Ontario. Resident Visiting Policy Questions. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ltc/faq_20200715.aspx (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Government of Ontario. COVID-19 Guidance Document for Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/covid-19-guidance-document-long-term-care-homes-ontario (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Whitehead, M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot. Int. 1991, 6, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Gruskin, S. Defining equity in health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, M.; Wong, R.Y. The impact of limiting family visits in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia. UBC Med. J. 2021, 12, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, J. Social Isolation—The Other COVID-19 Threat in Nursing Homes. JAMA 2020, 324, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Cook, K.; Hynan, L.; Chafetz, P.K.; Weiner, M.F. Impact of family visits on agitation in residents with dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2001, 16, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, R.; van Schalkwyk, M.C.; Akl, E.A.; Kristjannson, E.; Lotfi, T.; Petkovic, J.; Petticrew, M.P.; Pottie, K.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V. A framework for identifying and mitigating the equity harms of COVID-19 policy interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 128, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity. 2011. US Department of Health and Human Services Published Online First: 2011. Available online: https://www.phdmc.org/program-documents/healthy-lifestyles/dche/64-achieving-health-equity/file (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Agarwal, A.; Saad, A.; Magwood, O.; Benjamen, J.; Hashmi, S.S.; Haridas, R.; Sayfi, S.; Pottie, K. Examining the Health Equity Implications of Rapidly Emerging COVID-19 Visitation Strategies to LongTerm Care Homes in Ontario: A Protocol for A Mixed-Methods Study. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/projects/global-mental-health (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- O’cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, T.W.; Grant, S.; Welch, V.; Petkovic, J.; Selby, J.; Crowe, S.; Synnot, A.; Greer-Smith, R.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Tambor, E.; et al. Practical Guidance for Involving Stakeholders in Health Research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodman, M.S.; Thompson, V.L.S. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: Classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Government of Ontario. Find Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ltc/home-finder.aspx (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Hoddinott, S.N.; Bass, M.J. The dillman total design survey method. Can. Fam. Physician 1986, 32, 2366. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pottie, K.; Magwood, O.; Rahman, P.; Concannon, T.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Garcia, A.J.; Santesso, N.; Thombs, B.; Welch, V.; Wells, G.A.; et al. GRADE Concept Paper 1: Validating the “FACE” instrument using stakeholder perceptions of feasibility, acceptability, cost, and equity in guideline implement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 131, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Coello, P.; Oxman, A.D.; Moberg, J.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Akl, E.A.; Davoli, M.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; O Vandvik, P.; Meerpohl, J.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: A systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016, 353, i2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otter.ai-Otter-Mated Meeting Notes. Available online: https://otter.ai/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Altman, D.G.; Machin, D.; Bryant, T.N.; Gardner, M.J.; Auton, T. eds 2000: Statistics with Confidence, 2nd ed.; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 0 7279 1375 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVivo-Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Haynes-Brown, T.K.; Fetters, M.D. Using Joint Display as an Analytic Process: An Illustration Using Bar Graphs Joint Displays from a Mixed Methods Study of How Beliefs Shape Secondary School Teachers’ Use of Technology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1609406921993286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Welch, V.; Morton, R.; Akl, E.A.; Eslava-Schmalbach, J.H.; Katikireddi, V.; Singh, J.; Moja, L.; Lang, E.; Magrini, N.; et al. GRADE equity guidelines 4: Considering health equity in GRADE guideline development: Evidence to decision process. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 90, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moore, J. Placing home in context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HA, T. How Quebec’s Response to COVID-19 Left 4000 Dead in Long-Term Care Homes. The Globe and Mail. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-how-quebecs-response-to-covid-19-left-4000-dead-in-long-term-care/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Hindmarch, W.; McGhan, G.; Flemons, K.; McCaughey, D. COVID-19 and Long-Term Care: The Essential Role of Family Caregivers. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelen, S.; Boogaard, W.V.D.; Pellecchia, U.; Spiers, S.; De Cramer, C.; Demaegd, G.; Fouqueray, E.; Bergh, R.V.D.; Goublomme, S.; Decroo, T.; et al. How to bring residents’ psychosocial well-being to the heart of the fight against COVID-19 in Belgian nursing homes—A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Baan, F.; Aarts, S.; Verbeek, H. Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Video Calling for Connecting with Family Residing in Nursing Homes. IPA Bull. 2020, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. Long-Term Care Homes Act. 2007. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/100079 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Naudé, B.; Rigaud, A.-S.; Pino, M. Video Calls for Older Adults: A Narrative Review of Experiments Involving Older Adults in Elderly Care Institutions. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 751150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hado, E.; Friss Feinberg, L. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, meaningful communication between family caregivers and residents of long-term care facilities is imperative. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strang, V.R.; Koop, P.M.; Dupuis-Blanchard, S.; Nordstrom, M.; Thompson, B. Family Caregivers and Transition to Long-Term Care. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2006, 15, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Standards. Long-Term Care Services, 11.020.10. March. 2021. Available online: https://healthstandards.org/standards/notices-of-intent/long-term-care-services/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Laucius, J. New Standards Are Being Created for LTC Homes—and the Public is Asked to Weigh in. The Ottawa Citizen. Available online: https://ottawacitizen.com/health/new-standards-are-being-created-for-ltc-homes-and-the-public-is-asked-to-weigh-in (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Characteristics of Nursing Homes and Other Residential Long-Term Care Settings for People with Dementia; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville (MD): Rockville, MA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/dementia-nursing-home-characteristics/research-protocol (accessed on 12 December 2021).

| Visitation Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Designated caregivers | An essential visitor designated by the resident and/or their substitute decision-maker to visit and provide direct care to the resident (e.g., supporting feeding, mobility, personal hygiene, cognitive stimulation, communication, meaningful connection, relational continuity, and assistance in decision-making) [27]. Also referred to as: Essential visitors, designated care partners, and essential caregivers. |

| Outdoor visits | Visitors may visit an LTC resident at an outdoor space/setting, based on scheduling with the homes. Recognising that not all homes have suitable outdoor space, outdoor visits may also take place in the general vicinity of the home [27]. |

| Window visits | Residents can meet a visitor or a small group of visitors at a window within the LTC home. |

| Virtual visits | Connect by video teleconferencing software, such as Skype, FaceTime or Zoom. |

| Audio/video recorded messages | Record an audio or video message and send it to an LTC resident for them to watch/listen to. |

| Printed emails read by staff | Send a letter by email to an LTC resident and an LTC staff reads the letter to the resident. |

| Characteristic | Survey Participants (n = 201) | Interview Participants (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD (Range) | M | SD (Range) | |

| Age | 53.51 | 14.03 (21–85) | 58.4 | 10.87 (29–73) |

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25 | 12.4 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Female | 175 | 87.1 | 10 | 66.7 |

| Other | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| Canada | 168 | 83.6 | 9 | 60 |

| Other | 33 | 16.4 | 6 | 40 |

| Stakeholder group | ||||

| A family/relative of an LTC home resident | 96 | 47.8 | 14 * | 93.3 |

| Healthcare workers (both clinical and managerial) | 96 | 47.8 | 0 | 0 |

| LTC resident | 4 | 2.0 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Other | 5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 |

| This theme was built upon asking participants about their experiences and stories with LTC visits during the COVID-19 pandemic and is seldom qualitative in nature. |

| Subthemes: The “initial lockdown” |

|

| The initial lockdown and restricting visits to LTC residents were perceived as unfair and in violation of residents’ rights to access their support network. |

Supportive quotes:

|

| Subthemes: |

| |

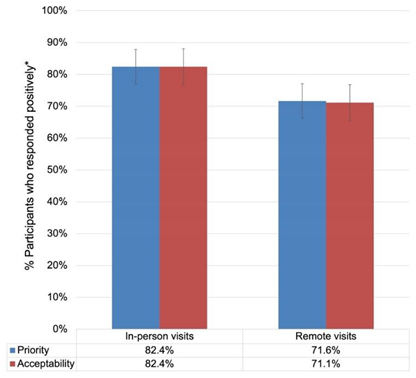

| Comparison 1: In-person visits were rated to be more prioritised than remote visits: Difference = 10.8%; 95% CI [2.64%, 18.96%]. Within-trend differences: More “yes” than “probably yes” responses; more “probably no” than “no” responses. (See Supplementary File S3) Comparison 2: In-person visits were rated to be more acceptable than remote visits: Difference = 11.3; 95% CI [3.12%, 19.48%]. Within-trend differences: More “yes” than “probably yes” responses; more “no” than “probably no” responses for in-person-visits, and the opposite for remote visits. (See Supplementary File S3) | Supportive quote:

|

| Subthemes: |

| |

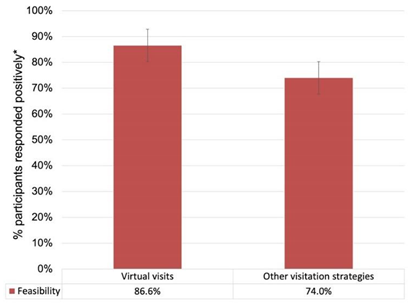

| Comparison 3: Virtual visits were rated to be more feasible than other visitation strategies: Difference = 12.6%; 95% CI [4.92%, 20.28%]. Within-trend differences: More “yes” than “probably yes” responses; more “probably no” than “no” responses. (See Supplementary File S3) | Supportive quote:

|

| Subthemes: |

| |

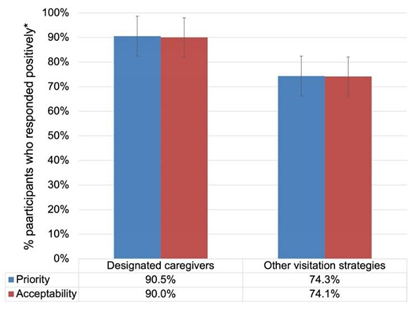

| Comparison 4: Designated caregivers were rated to be more prioritised than other visitation strategies: Difference = 16.2%; 95% CI [8.93%, 23.47%]. Within-trend differences: More “yes” than “probably yes” responses; more “probably no” than “no” responses. (See Supplementary File S3) Comparison 5: Designated caregivers were rated to be more acceptable than other visitation strategies: Difference = 15.9%; 95% CI [8.56%, 23.24%]. Within-trend differences: More “yes” than “probably yes” responses; more “probably no” than “no” responses. (See Supplementary File S3) | Supportive quote:

|

| Health Equity Implications | Justification |

|---|---|

| Participants highlighted the unfairness and negative unintended consequences of the initial lockdown, and emphasised that such aggressive measures cannot be implemented again. | Locking down homes disconnected LTC residents from their family members, friends, and community and confined them to their rooms, often without compensating care. This lockdown sparked feelings of loneliness and isolation and had a detrimental effect on their well-being. |

| Future visitation strategies should be designed to maintain emotional value for LTC residents and their family members, allowing for in-person interactions in a safe and visit-friendly environment. | Transitional visitation strategies may have provided means to connect LTC residents to their family members, but participants highlighted that they lacked the emotional value needed to sustain their benefit for both the resident and care partners in the long run. |

| Designated caregiver programs may provide LTC residents with emotional connection and family caregiving, but such programs must also be accessible and adapted to the needs level and context of residents and their family members. | Participants emphasised that many LTC residents need sustained caregiving from their support network. They highlighted designated caregivers as the most prioritised and most acceptable form of visitation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saad, A.; Magwood, O.; Benjamen, J.; Haridas, R.; Hashmi, S.S.; Girard, V.; Sayfi, S.; Unachukwu, U.; Rowhani, M.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Health Equity Implications of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Visitation Strategies in Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario: A Mixed Method Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074275

Saad A, Magwood O, Benjamen J, Haridas R, Hashmi SS, Girard V, Sayfi S, Unachukwu U, Rowhani M, Agarwal A, et al. Health Equity Implications of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Visitation Strategies in Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario: A Mixed Method Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074275

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaad, Ammar, Olivia Magwood, Joseph Benjamen, Rinila Haridas, Syeda Shanza Hashmi, Vincent Girard, Shahab Sayfi, Ubabuko Unachukwu, Melody Rowhani, Arunika Agarwal, and et al. 2022. "Health Equity Implications of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Visitation Strategies in Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario: A Mixed Method Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074275

APA StyleSaad, A., Magwood, O., Benjamen, J., Haridas, R., Hashmi, S. S., Girard, V., Sayfi, S., Unachukwu, U., Rowhani, M., Agarwal, A., Fleming, M., Filip, A., & Pottie, K. (2022). Health Equity Implications of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Visitation Strategies in Long-Term Care Homes in Ontario: A Mixed Method Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074275