Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The COVID-19 lockdown would affect the mental health of children and adolescents from Spain. In particular, we assumed that they would show significantly higher emotional and behavioral problems during home quarantine than before the COVID-19 outbreak.

- The mental health impairment experienced by children and adolescents would be associated with their sociodemographic characteristics, situation prior to home quarantine, physical environment and accompaniment during the lockdown, and COVID-related variables (e.g., concerns about health, presence of learning problems and economic difficulties in the family caused by the pandemic). For instance, we expected that those with preexisting mental conditions, such as emotional/behavioral problems and neurodevelopmental disorders, or limited housing facilities would be particularly vulnerable to the potentially negative effects of quarantine. In contrast, maintaining social interaction, albeit remotely, with family members, friends, classmates, and teachers, as well as daily life routines, would be protective factors.

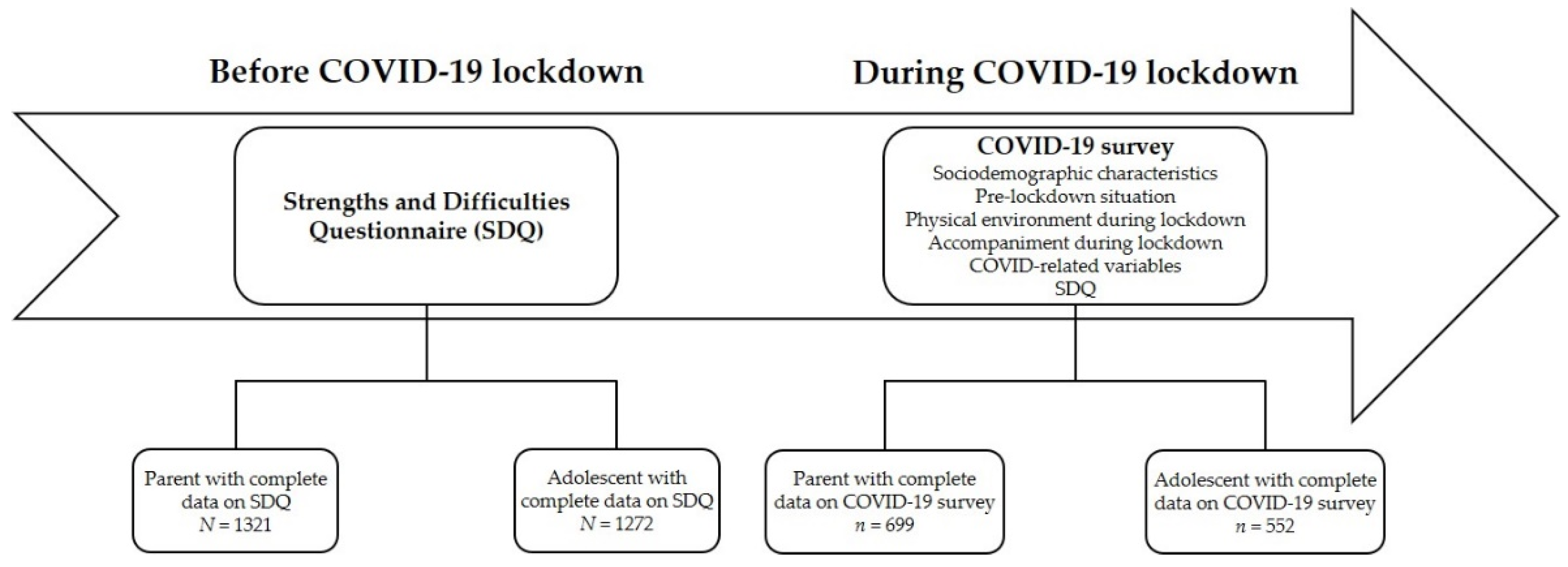

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Changes in Psychological Symptoms before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown

3.3. Factors Influencing Mental Health Impairment during COVID-19 Lockdown

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Eccles, J.S. Participation in extracurricular activities in middle school years: Are there developmental benefits for African American and European American Youth? J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.J.; Schmidt, C.; Abraham, A.; Walker, L.; Tercyak, K. Adolescents’ social environment and depression: Social networks, extracurricular activity, and family relationship influences. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2009, 16, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbele, E.; Xi, X.R.; Kerai, S.; Guhn, M.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Gaderman, A.M. Screen time and extracurricular activities as risk and protective factors for mental health in adolescence: A population-level study. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106291. [Google Scholar]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprang, G.; Silman, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2013, 7, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anniko, M.K.; Boersma, K.; Tillfors, M. Investigating the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in the development of adolescent emotional problems. Nord. Psychol. 2018, 70, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, A.; Goenjian, A.K.; Steinberg, A.M.; Sotiropoulou, C.; Kakaki, M.; Kabakos, C.; Karagianni, S.; Manouras, V. Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake in Ano Liosia, Greece. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E.; McGinnis, E.; Bai, Y.; Adams, Z.; Nardone, H.; Devadanam, V.; Rettew, J.; Hudziak, J.J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.Y.; Wang, L.N.; Liu, J.; Fang, S.F.; Jiao, F.Y.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Somekh, E. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Pediatrics 2020, 221, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, W.; Chen, Z. Latent profiles of the comorbidity of the symptoms for posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder among children and adolescents who are susceptible to COVID-19. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Chen, X.; Yuan, X.F.; Li, Y.Q.; Huang, H.H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, G. Prevalence of anxiety and associated factors for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.J.; Zhang, L.G.; Wang, L.L.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, J.C.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.X. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearchou, F.; Flinn, C.; Niland, R.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Hennessy, E. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Delecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J.P. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 579038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, L.; Navarro, J.B.; de la Osa, N.; Trepat, E.; Penelo, E. Life conditions during COVID-19 lockdown and mental health in Spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, G.S.; Clarke-Pearson, K.; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Billieux, J.; Potenza, M.N. Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.A.; Choo, H.; Liau, A.; Sim, T.; Li, D.; Fung, D.; Khoo, A. Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e319–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gentile, D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: A national study. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T.; Parker, P.D.; Del Pozo-Cruz, B.; Noetel, M.; Lonsdale, C. Type of screen time moderates effects on outcomes in 4013 children: Evidence from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. 2019, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassman-Pines, A.; Ananat, E.O.; Fitz-Henley, J. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020007294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Schlack, R.; Otto, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Song, R. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics 2020, 174, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bobo, E.; Lin, L.; Acquaviva, E.; Caci, H.; Franc, N.; Gamon, L.; Picot, M.C.; Pupier, F.; Speranza, M.; Falissard, B.; et al. How do children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) experience lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak. Encephale 2020, 46, S85–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Asherson, P.; Sonuga-Barke, E.; Banaschewski, T.; Brandeis, D.; Buitelaar, J.; Coghill, D.; Daley, D.; Danckaerts, M.; Dittmann, R.W.; et al. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: Guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smile, S.C. Supporting children with autism spectrum disorder in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ 2020, 192, E587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neece, C.; McIntyre, L.L.; Fenning, R. Examining the impact of COVID-19 in ethnically diverse families with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shuai, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Lu, L.; Cao, X.; Xia, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R. Acute stress, behavioral symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonweiler, J.; Rattray, F.; Baulcomb, J.; Happé, F.; Absoud, M. Prevalence and associated factors of emotional and behavioral difficulties during COVID-19 pandemic in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Children 2020, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, R.; Pagerols, M.; Rivas, C.; Sixto, L.; Bricollé, L.; Español-Martín, G.; Prat, R.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Casas, M. Neurodevelopmental disorders among Spanish school-age children: Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Psychol. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Español-Martín, G.; Pagerols, M.; Prat, R.; Rivas, C.; Sixto, L.; Valero, S.; Soler-Artigas, M.; Ribasés, M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Casas, M.; et al. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and normative data for Spanish 5- to 17-year-olds. Assessment 2021, 28, 1445–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci. 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.W.; Saridjan, N.S.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Verhulst, F.C.; Tiemeier, H. Does disturbed sleeping precede symptoms of anxiety or depression in toddlers? The generation R study. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovato, N.; Gradisar, M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: Recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med. Rev. 2014, 18, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.; Copeland-Stewart, A. Playing video games during the COVID-19 pandemic and effects on players’ well-being. Games Cult. 2022, 17, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, A.; Di Blasi, M.; Schimmenti, A.; King, D.L.; Starcevic, V.; Billieux, J. Online gaming and prolonged self-isolation: Evidence from Italian gamers during the Covid-19 outbreak. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Vaderloo, L.M.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Cost, K.T.; Charach, A.; Maguire, J.L.; Monga, S.; Crosbie, J.; Burton, C.; Anagnostou, E.; et al. Screen use and mental health symptoms in Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e21408575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavelier, D.; Green, C.S.; Han, D.H.; Renshaw, P.F.; Merzenich, M.M.; Gentile, D.A. Brains on video games. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smirni, D.; Garufo, E.; Di Falco, L.; Lavanco, G. The playing brain. The impact of video games on cognition and behavior in pediatric age at the time of lockdown: A systematic review. Pediatric Rep. 2021, 13, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, M.A.; Guido, C.A.; De Meo, G.; Spalice, A.; Sanson, F.; Beccari, C.; Primi, C. Gaming among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown: The role of parents in time spent on video games and gaming disorder symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C. A novel approach of consultation on 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)-related psychological and mental problems: Structured letter therapy. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manuell, M.E.; Cukor, J. Mother Nature versus human nature: Public compliance with evacuation and quarantine. Disasters 2011, 35, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Giacco, D.; Forsyth, R.; Nebo, C.; Mann, F.; Johnson, S. Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Yim, H.W.; Song, Y.J.; Ki, M.; Min, J.A.; Cho, J.; Chae, J.H. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol. Health 2016, 38, e2016048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihashi, M.; Otsubo, Y.; Yinjuan, X.; Nagatomi, K.; Hoshiko, M.; Ishitake, T. Predictive factors of psychological disorder development during recovery following SARS outbreak. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Parent-Reported Sample (N = 699) | Adolescent-Reported Sample (N = 552) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 362 (51.8) | 217 (39.3) |

| Female | 337 (48.2) | 335 (60.7) |

| Age, M (SD) | 12.5 (3.19) | 14.8 (0.62) |

| Type of school, n (%) | ||

| Public | 511 (73.1) | 341 (61.8) |

| Private | 188 (26.9) | 211 (38.2) |

| Educational stage, n (%) | ||

| Primary | 245 (35.1) | ― |

| Secondary | 454 (64.9) | 552 (100.0) |

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Family environment, n (%) | ||

| Bad or very bad | 3 (0.43) | 12 (2.17) |

| Average | 55 (7.89) | 108 (19.6) |

| Very good or good | 641 (91.7) | 432 (78.2) |

| Child’s mood, n (%) | ||

| Insomnia | 21 (3.00) | 62 (11.2) |

| Hypersomnia | 12 (1.72) | 24 (4.35) |

| Waking up multiple times at night | 26 (3.72) | 58 (10.5) |

| Disorganized sleep schedule | 13 (1.86) | 25 (4.53) |

| Loss of appetite | 23 (3.29) | 40 (7.25) |

| Increased appetite | 21 (3.00) | 30 (5.43) |

| Euphoria | 13 (1.86) | 16 (2.90) |

| Irritability | 78 (11.2) | 68 (12.3) |

| Exaggerated worries | 31 (4.43) | 55 (9.96) |

| Sadness | 20 (2.86) | 70 (12.7) |

| Nervousness | 83 (11.9) | 131 (23.7) |

| Use of alcohol or other drugs | 1 (0.14) | 9 (1.63) |

| Aggressiveness | 8 (1.14) | 20 (3.62) |

| Child’s behavior, n (%) | ||

| Bad or very bad | 5 (0.72) | 13 (2.36) |

| Average | 96 (13.7) | 134 (24.3) |

| Very good or good | 598 (85.6) | 405 (73.4) |

| Presence of ND, n (%) | 164 (23.5) | ― |

| Video games use, n (%) | 403 (57.7) | 272 (49.3) |

| Physical environment during lockdown | ||

| Length of lockdown (days), M (SD) | 78.8 (5.12) | 78.7 (5.29) |

| City of residence, n (%) | ||

| <2000 inhabitants | 8 (1.14) | 9 (1.63) |

| 2000–10,000 inhabitants | 80 (11.4) | 61 (11.1) |

| 10,000–50,000 inhabitants | 208 (29.8) | 264 (47.8) |

| >50,000 inhabitants | 403 (57.7) | 215 (38.9) |

| Comfort Home (range = 2–11), M (SD) | 7.39 (2.28) | 6.31 (3.04) |

| Study Facilities (range = 1–7), M (SD) | 5.44 (1.47) | 5.75 (1.40) |

| Accompaniment during lockdown | ||

| People sharing lockdown—parents, n (%) | ||

| Both parents | 606 (86.7) | 474 (85.9) |

| Single parent | 88 (12.6) | 75 (13.6) |

| No parents | 5 (0.72) | 3 (0.54) |

| People sharing lockdown—siblings, n (%) | ||

| No siblings | 183 (26.2) | 107 (19.4) |

| 1 sibling | 412 (58.9) | 289 (52.4) |

| 2 siblings | 89 (12.7) | 105 (19.0) |

| ≥3 siblings | 15 (2.15) | 50 (9.06) |

| Online communication with relatives, n (%) | ||

| 1 (Not at all) | 16 (2.29) | 26 (4.71) |

| 2 | 72 (10.3) | 57 (10.3) |

| 3 | 183 (26.2) | 99 (17.9) |

| 4 | 202 (28.9) | 166 (30.1) |

| 5 (Extremely) | 226 (32.3) | 204 (37.0) |

| Online communication with friends, n (%) | ||

| 1 (Not at all) | 18 (2.58) | 14 (2.54) |

| 2 | 94 (13.4) | 38 (6.88) |

| 3 | 164 (23.5) | 93 (16.8) |

| 4 | 174 (24.9) | 129 (23.4) |

| 5 (Extremely) | 249 (35.6) | 278 (50.4) |

| Participation in online classes, n (%) | ||

| 1 (Never) | 44 (6.29) | 11 (1.99) |

| 2 (Occasionally) | 96 (13.7) | 51 (9.24) |

| 3 (Once a week) | 197 (28.2) | 38 (6.88) |

| 4 (2–3 times a week) | 150 (21.5) | 108 (19.6) |

| 5 (Every day) | 212 (30.3) | 344 (62.3) |

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Economic problems, n (%) | 252 (36.1) | 136 (24.6) |

| Concerned about health problems, n (%) | ||

| 1 (Not at all) | 127 (18.2) | 67 (12.1) |

| 2 | 143 (20.5) | 98 (17.8) |

| 3 | 179 (25.6) | 166 (30.1) |

| 4 | 119 (17.0) | 120 (21.7) |

| 5 (Extremely) | 131 (18.7) | 101 (18.3) |

| Children diagnosed with COVID-19, n (%) | 6 (0.85) | 9 (1.63) |

| Relative or friend got COVID-19, n (%) | 146 (20.9) | 161 (29.1) |

| Relative or friend hospitalized because of COVID-19, n (%) | 51 (7.29) | 63 (11.4) |

| Relative or friend died because of COVID-19, n (%) | 14 (2.00) | 21 (3.80) |

| Before Lockdown | During Lockdown | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ Parent (N = 699) | M (SD) | M (SD) | p | Effect Size (r) |

| Emotional symptoms | 1.63 (1.85) | 2.16 (2.03) | <0.001 | 0.19 |

| Conduct problems | 1.26 (1.52) | 1.74 (1.51) | <0.001 | 0.25 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | 2.99 (2.53) | 3.85 (2.67) | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| Peer problems | 1.13 (1.55) | 1.65 (1.67) | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| Prosocial behavior | 7.82 (1.88) | 7.87 (1.69) | ― | |

| Total difficulties | 7.02 (5.57) | 9.40 (5.61) | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| SDQ adolescent (N = 552) | ||||

| Emotional symptoms | 2.42 (2.14) | 3.29 (2.29) | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Conduct problems | 1.51 (1.49) | 1.92 (1.55) | <0.001 | 0.16 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | 3.42 (2.44) | 4.27 (2.52) | <0.001 | 0.25 |

| Peer problems | 1.27 (1.58) | 1.70 (1.67) | <0.001 | 0.18 |

| Prosocial behavior | 7.96 (1.71) | 7.81 (1.77) | 0.046 | 0.059 |

| Total difficulties | 8.62 (5.59) | 11.2 (5.62) | <0.001 | 0.33 |

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional symptoms | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Educational stage (reference: primary) | 1.62 (1.16–2.25) | 0.004 |

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Exaggerated worries (reference: no) | 3.01 (1.28–7.06) | 0.011 |

| Waking up multiple times at night (reference: no) | 2.87 (1.16–7.11) | 0.023 |

| Nervousness (reference: no) | 1.67 (1.01–2.75) | 0.046 |

| Video games use (reference: no) | 0.59 (0.43–0.81) | <0.001 |

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Perceived academic delay | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 0.018 |

| Conduct problems | ||

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Child’s behavior | 0.54 (0.42–0.70) | <0.001 |

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Following daily routines | 0.83 (0.71–0.98) | 0.027 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Gender (reference: female) | 1.41 (1.04–1.92) | 0.027 |

| Age | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 0.043 |

| Accompaniment during lockdown | ||

| Following virtual learning | 0.85 (0.55–0.99) | 0.035 |

| Peer problems | ||

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Sadness (reference: no) | 4.16 (1.47–11.8) | 0.007 |

| Video games use (reference: no) | 0.60 (0.44–0.82) | 0.001 |

| Accompaniment during lockdown | ||

| Online communication with friends | 0.74 (0.64–0.84) | <0.001 |

| Total difficulties | ||

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Presence of ND (reference: no) | 0.52 (0.36–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Video games use (ref. no) | 0.65 (0.46–0.90) | 0.011 |

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional symptoms | ||

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Waking up multiple times at night (reference: no) | 2.11 (1.14–3.93) | 0.018 |

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Health concerns | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) | 0.017 |

| Conduct problems | ||

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Academic advantage of lockdown | 0.81 (0.71–0.93) | 0.004 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | ||

| Physical environment | ||

| Study facilities | 0.83 (0.74–0.94) | 0.005 |

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Academic advantage of lockdown | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 0.001 |

| Peer problems | ||

| Pre-lockdown situation | ||

| Disorganized sleep schedule (reference: no) | 3.23 (1.32–7.92) | 0.010 |

| Accompaniment during lockdown | ||

| Online communication with friends | 0.79 (0.68–0.93) | 0.005 |

| Total difficulties | ||

| COVID-related variables | ||

| Economic problems (reference: no) | 1.88 (1.21–2.90) | 0.005 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosch, R.; Pagerols, M.; Prat, R.; Español-Martín, G.; Rivas, C.; Dolz, M.; Haro, J.M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Ribasés, M.; Casas, M. Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074120

Bosch R, Pagerols M, Prat R, Español-Martín G, Rivas C, Dolz M, Haro JM, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Ribasés M, Casas M. Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074120

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosch, Rosa, Mireia Pagerols, Raquel Prat, Gemma Español-Martín, Cristina Rivas, Montserrat Dolz, Josep Maria Haro, Josep Antoni Ramos-Quiroga, Marta Ribasés, and Miquel Casas. 2022. "Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074120

APA StyleBosch, R., Pagerols, M., Prat, R., Español-Martín, G., Rivas, C., Dolz, M., Haro, J. M., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Ribasés, M., & Casas, M. (2022). Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074120