Health Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Medical Staff

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Study Participants

2.2. Research Methodology and Tools

- −

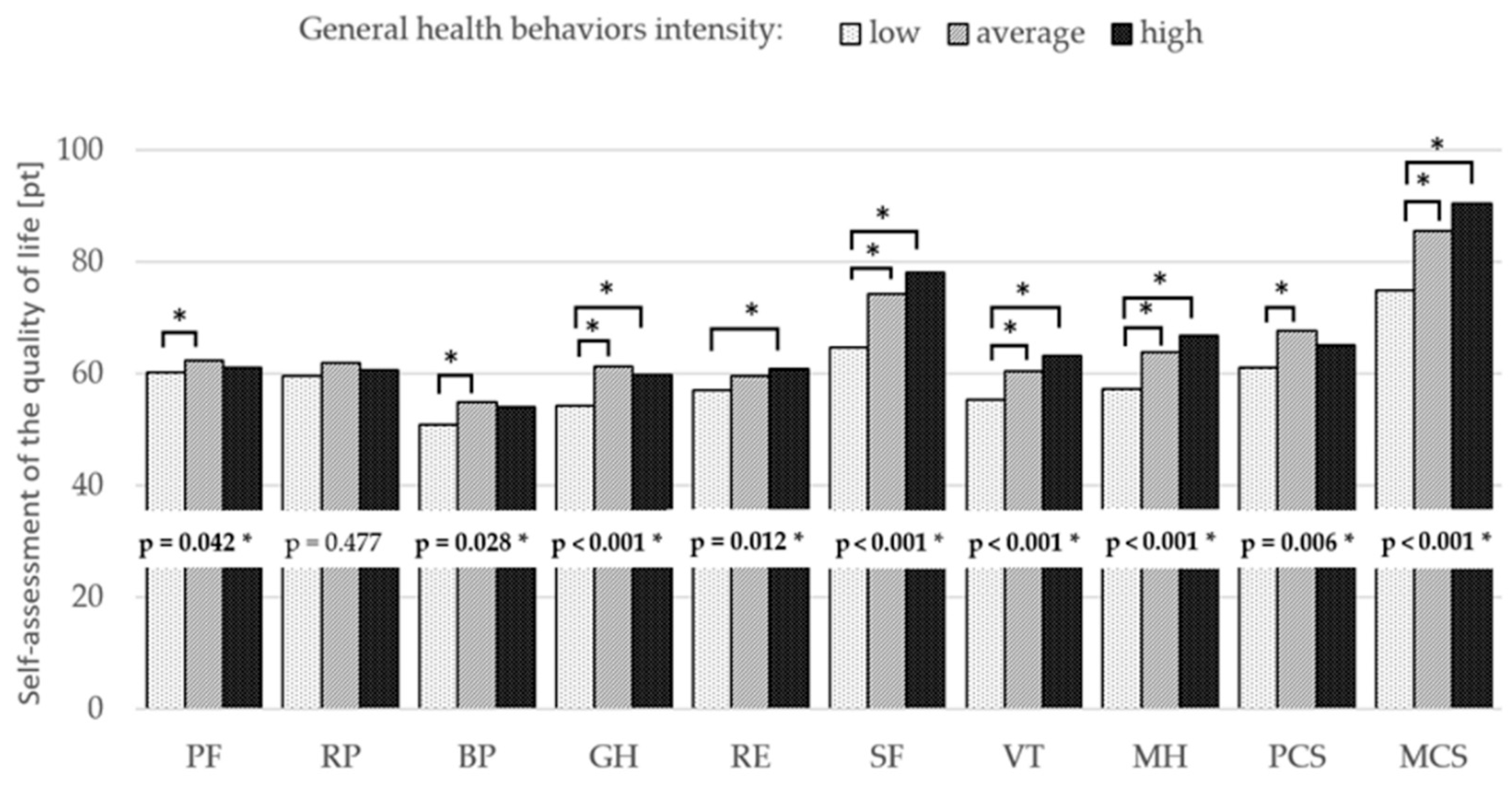

- Physical functioning (PF);

- −

- Role-physical (RP);

- −

- Bodily pain (BP);

- −

- General health (GH);

- −

- Vitality (VT);

- −

- Social functioning (SF);

- −

- Role-emotional (RE);

- −

- Mental health (MH).

- −

- Proper eating habits (PEH);

- −

- Pro-health activities (PhA);

- −

- Preventive actions (PA);

- −

- Positive mental attitude (PMA).

2.3. Research Procedure

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; WHO Library Cataloguing in-Publication Data: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Żołnierczyk-Zreda, D.; Wrześniewski, K.; Bugajska, J.; Jędryka-Góral, A. Polska Wersja Kwestionariusza SF-36v2 Do Badania Jakości Życia; Centralny Instytut Ochrony Pracy-Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wolanin, A. Quality of life in selected psychological concepts. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Q. 2021, 28, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulchinsky, T.H. Marc Lalonde, the health field concept and health promotion. In Case Studies in Public Health; Tulchinsky, T.H., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 523–541. [Google Scholar]

- Lusarska, B.; Kulik, T.; Piasecka, H.; Pacian, A. Knowledge of cardiovascular risk factors and health promoting behaviours among students of medicine. Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu 2012, 18, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Waksmańska, W.; Gajewska, K. Health behaviours of nursing staff working in a shift system in John Paul II District Hospital in Wadowice. Environ. Med. 2021, 22, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusz, K.; Kívés, Z.; Pakai, A.; Kutfej, N.; Deák, A.; Oláh, A. Health behavior, sleep quality and subjective health status among Hungarian nurses working varying shifts. Work 2021, 68, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajo, S.; Reed, J.L.; Hans, H.; Tulloch, H.E.; Reid, R.D.; Prince, S.A. Physical activity, sedentary time and sleep and associations with mood states, shift work disorder and absenteeism among nurses: An analysis of the cross-sectional Champlain Nurses’ Study. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennessy, E.A.; Johnson, B.T.; Acabchuk, R.L.; McCloskey, K.; Stewart-James, J. Self-regulation mechanisms in health behavior change: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses, 2006–2017. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 14, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Kelly, S.A.; Stephens, J.; Dhakal, K.; McGovern, C.; Tucker, S.; Hoying, J.; McRae, K.; Ault, S.; Spurlock, E.; et al. Interventions to Improve Mental Health, Well-Being, Physical Health, and Lifestyle Behaviors in Physicians and Nurses: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.; Prestwich, A.; Quested, E.; Hancox, J.E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Lonsdale, C.; Williams, G.C. A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 214–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teychenne, M.; White, R.L.; Richards, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Bennie, J.A. Do we need physical activity guidelines for mental health: What does the evidence tell us? Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 18, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hell-Cromwijk, M.; Metzelthin, S.F.; Schoonhoven, L.; Verstraten, C.; Kroeze, W.; Ginkel, J.M.d.M.v. Nurses’ perceptions of their role with respect to promoting physical activity in adult patients: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2540–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynarski, W.; Grabara, M.; Nawrocka, A.; Niestrój-Jaworska, M.; Wołkowycka, B.; Cholewa, J. Physical recreational activity and musculoskeletal disorders in nurses. Med. Pract. 2014, 65, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- WCRF. The Link between Food, Nutrition, Diet and Non-Communicable Diseases; WCRF: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Sekyere, F. Assessing the effect of physical activity and exercise on nurses’ well-being. Nurs. Stand. 2020, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagody-Mrozowicz, K.; Puciato, D.; Rozpara, M.; Markiewicz-Patkowska, J. Behaviour Determinants in the Research for Health-Related Quality of Life and Physical Activity of Urban Adults from Single-Person Households. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, A.; Polechoński, J.; Garbaciak, W.; Mynarski, W. Functional Fitness and Quality of Life among Women over 60 Years of Age Depending on Their Level of Objectively Measured Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puciato, D.; Rozpara, M.; Borysiuk, Z. Physical Activity as a Determinant of Quality of Life in Working-Age People in Wrocław, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dębska, M.; Dębski, P.; Miara, A. Self-assessment of health-related quality of life in adults involved in regular physical activity. Ann. Acad. Med. Silesiensis 2017, 72, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, P.; Katsikavali, V.; Galanis, P.; Velonakis, E.; Papadatou, D.; Sourtzi, P. Impact of Job Satisfaction on Greek Nurses' Health-Related Quality of Life. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zwierzchowska, A.; Żebrowska, A.; Szkwara, M. Sports activities and satisfaction of living of men after cervical spinal cord injury. Pol. Ann. Med. 2019, 24, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanulewicz, N.; Knox, E.; Narayanasamy, M.; Shivji, N.; Khunti, K.; Blake, H. Effectiveness of Lifestyle Health Promotion Interventions for Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biernat, E.; Poznańska, A.; Gajewski, A.K. Is Physical Activity of Medical Personnel a Role Model for Their Patients. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 19, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, N.A.; Alaskar, A.; Almuflih, A.; Muhanna, N.; Alzomia, S.B.; Hussein, M.A. Screening Practices, Knowledge and Adherence Among Health Care Professionals at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 6975–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, H.; Gore, R.J.; Boyer, J.; Nobrega, S.; Punnett, L. Health Behaviors and Overweight in Nursing Home Employees: Contribution of Workplace Stressors and Implications for Worksite Health Promotion. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, e915359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiou, S.-T.; Chiang, J.-H.; Huang, N.; Chien, L.-Y. Health behaviors and participation in health promotion activities among hospital staff: Which occupational group performs better? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.K.; D’Silva, F. Job Satisfaction, Burnout and Quality of Life of Nurses from Mangalore. J. Health Manag. 2013, 15, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Segura, C. Health practices of Canadian physicians. Can. Fam. Physician 2009, 55, 810–811.e7. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, T.; Maghaminejad, F.; Azizi-Fini, I. Quality of Working Life of Nurses and Its Related Factors. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2014, 3, e19450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L.; Xu, X.; Gallagher, R.; Nicholls, R.; Sibbritt, D.; Duffield, C. Lifestyle Health Behaviors of Nurses and Midwives: The ‘Fit for the Future’ Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rostami, A.; Ghazinour, M.; Nygren, L.; Nojumi, M.; Richter, J. Health-related Quality of Life, Marital Satisfaction, and Social Support in Medical Staff in Iran. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2013, 8, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiraoui, F.; Gualano, M.; Mannocci, A.; Boccia, A.; La Torre, G. Quality of life among healthcare workers: A multicentre cross-sectional study in Italy. Public Health 2012, 126, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewko, J.; Misiak, B.; Sierżantowicz, R. The Relationship between Mental Health and the Quality of Life of Polish Nurses with Many Years of Experience in the Profession: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suñer-Soler, R.; Grau-Martín, A.; Font-Mayolas, S.; Gras, M.E.; Bertran, C.; Sullman, M.J.M. Burnout and quality of life among Spanish healthcare personnel. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruish, M. User’s Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey; Quality Metric Incorporated: Johnston, RI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Psychologii Zdrowia; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi, S.; While, A.E. Health Professionals’ Alcohol-Related Professional Practices and the Relationship between Their Personal Alcohol Attitudes and Behavior and Professional Practices: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 218–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helfand, B.K.I.; Mukamal, K.J. Healthcare and Lifestyle Practices of Healthcare Workers: Do Healthcare Workers Practice What They Preach? JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peplonska, B.; Bukowska, A.; Sobala, W. Rotating Night Shift Work and Physical Activity of Nurses and Mid-wives in the Cross-Sectional Study in L. Ódź, Poland. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roveda, E.; Castelli, L.; Galasso, L.; Mulè, A.; Cè, E.; Condemi, V.; Banfi, G.; Montaruli, A.; Esposito, F. Differences in Daytime Activity Levels and Daytime Sleep Between Night and Day Duty: An Observational Study in Italian Orthopedic Nurses. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 628231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiga, E.; Panagopoulou, E.; Niakas, D. Health promotion across occupational groups: One size does not fit all. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brand, S.L.; Coon, J.T.; Fleming, L.E.; Carroll, L.; Bethel, A.; Wyatt, K. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amin, K.; Hafeez, S.; Hassan, D.; Zahid, S. Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Physiotherapists. J. Riphah Coll. Rehabil. Sci. 2018, 6, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Ratcliffe, J.; Olds, T.; Magarey, A.; Jones, M.; Leslie, E. BMI, Health Behaviors, and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents: A School-Based Study. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e868–e874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopinath, B.; Hardy, L.L.; Baur, L.A.; Burlutsky, G.; Mitchell, P. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e167–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priano, S.M.; Hong, O.S.; Chen, J.-L. Lifestyles and Health-Related Outcomes of US Hospital Nurses: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Outlook 2018, 66, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D. Occupational Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life in Nursing Professionals: A Multi-Centre Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Su, T.T.; Azzani, M.; Adewale, A.P.; Thangiah, N.; Zainol, R.; Majid, H. Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Low-Income Adults in Metropolitan Kuala Lumpur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurpas, D.; Mroczek, B.; Jasinska, M.; Bielska, D.; Nitsch-Osuch, A.; Kassolik, K.; Andrzejewski, W.M.; Gryko, A.; Krzyzanowski, D.M.; Steciwko, A. Health behaviors and quality of life among patients with chronic respiratory disease. In Neurobiology of Respiration; Pokorski, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 401–406. ISBN 978-94-007-6627-3. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, N.S.; Osann, K.; Hsieh, S.; Tucker, J.A.; Monk, B.J.; Nelson, E.L.; Wenzel, L. Health Behaviors in Cervical Cancer Survivors and Associations with Quality of Life. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nes, L.S.; Ehlers, S.L.; Patten, C.A.; Gastineau, D.A. Self-Regulatory Fatigue, Quality of Life, Health Behaviors, and Coping in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bunyamin, V.; Spaderna, H.; Weidner, G. Health behaviors contribute to quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure independent of psychological and medical patient characteristics. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Oh, J. Health-related quality of life in older adults: Its association with health literacy, self-efficacy, social support, and health-promoting behavior. Healthcare 2020, 8, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, T.W.; Chapman, D.P.; Balluz, L.S.; Moriarty, D.G.; Mokdad, A.H. The Associations Between Life Satisfaction and Health-related Quality of Life, Chronic Illness, and Health Behaviors among U.S. Community-dwelling Adults. J. Community Health 2007, 33, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, S.; Vuillemin, A.; Bertrais, S.; Boini, S.; Le Bihan, E.; Oppert, J.-M.; Hercberg, S.; Guillemin, F.; Briançon, S. Association between leisure-time physical activity and health-related quality of life changes over time. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel-Vos, G.; Schuit, J.; Tijhuis, M.; Kromhout, D. Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova-Karamanova, A.; Todorova, I.; Montgomery, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Costa, P.; Baban, A.; Davas, A.; Milosevic, M.; Mijakoski, D. Burnout and health behaviors in health professionals from seven European countries. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 1059–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.M. Work–family and family–work conflicts and health: The protective role of work engagement and job-related subjective well-being. Med. Pract. 2020, 71, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, D.; Damayanti, N.A. Healthy nurses for a quality health care service: A literature review. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heath Related Quality of Life | ||

| Variable [pt] | ±SD | Min-Max |

| PF | 61.2 ± 4.6 | 39.7–64.6 |

| RP | 60.8 ± 7.1 | 35.9–66.9 |

| BP | 53.3 ± 8.6 | 36.6–66.6 |

| GH | 58.5 ± 8.9 | 38.0–76.0 |

| RE | 59.1 ± 6.2 | 32.1–62.9 |

| SF | 72.2 ± 14.2 | 36.3–85.1 |

| VT | 59.4 ± 9.7 | 18.3–85.6 |

| MH | 62.4 ± 9.2 | 27.1–81.4 |

| PCS | 64.7 ± 10.1 | 34. 2–80.4 |

| MCS | 83.3 ± 15.3 | 21.4–97.1 |

| Heath Behavior | ||

| Variable [pt] | ±SD | Min-Max |

| PEH | 20.5 ± 4.9 | 6.0–30.0 |

| PA | 21.0 ± 4.2 | 9.0–30.0 |

| PMA | 21.6 ± 3.8 | 15.0–29.0 |

| PhA | 19.3 ± 3.6 | 11.0–28.0 |

| HBI | 82.4 ± 13.2 | 47.0–112.0 |

| Variable | PEH | PA | PMA | PhA | HBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rS p | rS p | rS p | rS p | rS p | |

| PF | 0.21 0.009 * | 0.07 0.37 | 0.13 0.116 | 0.18 0.026 * | 0.19 0.016 * |

| RP | 0.05 0.516 | −0.06 0.48 | 0.15 0.059 | 0.08 0.305 | 0.06 0.428 |

| BP | 0.2 0.015 * | 0.15 0.067 | 0.26 0.001 * | 0.25 0.002 * | 0.25 0.002 * |

| GH | 0.21 0.009 * | 0.1 0.207 | 0.32 <0.001 * | 0.3 <0.001 * | 0.29 <0.001 * |

| RE | 0.2 0.015 * | 0.08 0.333 | 0.31 <0.001 * | 0.25 0.002 * | 0.026 0.001 * |

| SF | 0.34 <0.001 * | 0.16 0.054 | 0.4 <0.001 * | 0.44 <0.001 * | 0.24 <0.001 * |

| VT | 0.22 0.007 * | 0.16 0.052 | 0.43 <0.001 * | 0.44 <0.001 * | 0.37 <0.001 * |

| MH | 0.28 <0.001 * | 0.23 0.004 * | 0.56 <0.001 * | 0.39 <0.001 * | 0.46 <0.001 * |

| PCS | 0.21 0.009 * | 0.08 0.303 | 0.27 0.001 * | 0.27 0.001 * | 0.25 0.002 * |

| MCS | 0.32 <0.001 * | 0.2 0.011 * | 0.53 <0.001 * | 0.46 <0.001 * | 0.47 <0.001 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niestrój-Jaworska, M.; Dębska-Janus, M.; Polechoński, J.; Tomik, R. Health Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Medical Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073896

Niestrój-Jaworska M, Dębska-Janus M, Polechoński J, Tomik R. Health Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Medical Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073896

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiestrój-Jaworska, Maria, Małgorzata Dębska-Janus, Jacek Polechoński, and Rajmund Tomik. 2022. "Health Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Medical Staff" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073896

APA StyleNiestrój-Jaworska, M., Dębska-Janus, M., Polechoński, J., & Tomik, R. (2022). Health Behaviors and Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Medical Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073896