Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction: Communication with Peers as a Mediator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction

1.2. Self-Esteem and Peer Communication

1.3. Peer Communication and Life Satisfaction

1.4. Peer Communication as a Mediator

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

2.3. Satisfaction with Life Scale

2.4. Scale of Communication of Adolescents with Peers

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlations

3.3. Multicollinearity and Confounding Variables

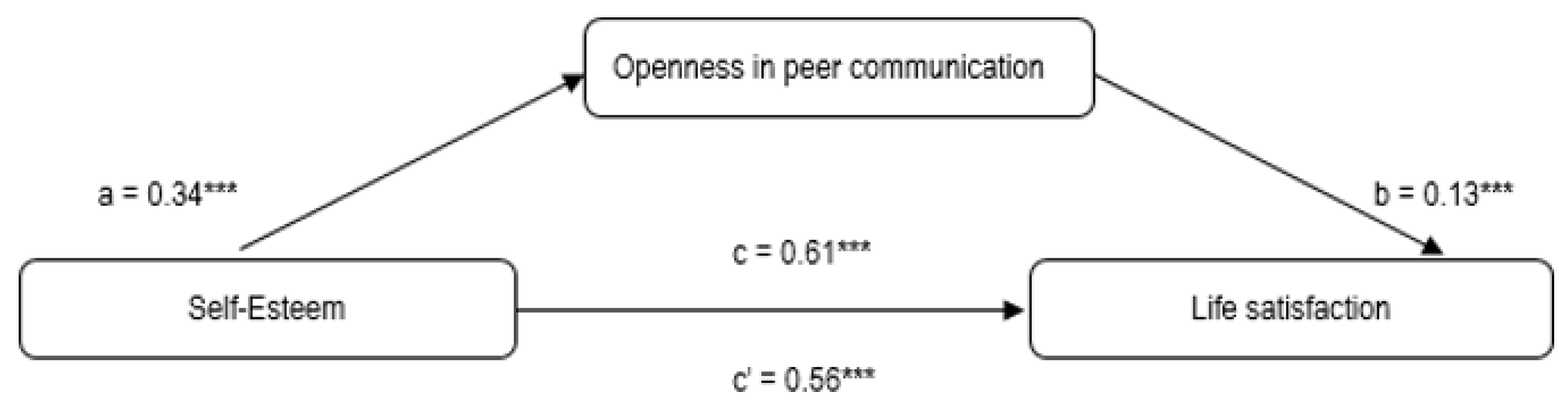

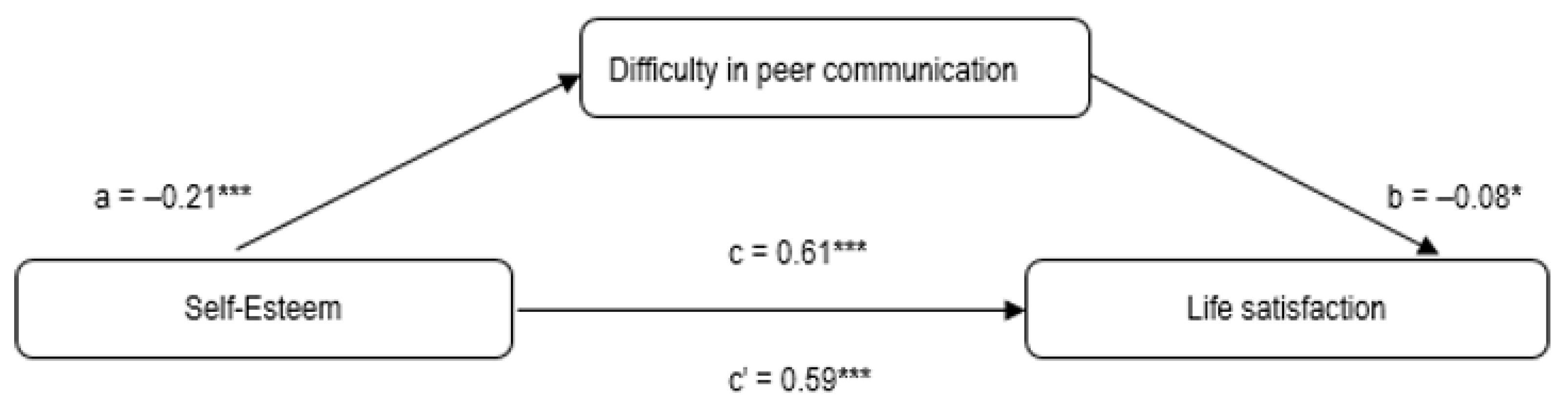

3.4. Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Investing in a Safe, Healthy and Productive Transition from Childhood to Adulthood is Critical. Adolescents Overview. 2019. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/ (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Adriana Sas. Number of Young People Aged 15–24 in Poland from 2008 to 2020. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1257255/poland-number-of-young-people/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Antaramian, S.P.; Huebner, E.S.; Valois, R.F. Adolescent life satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greischel, H.; Noack, P.; Neyer, F.J. Oh, the places you’ll go! How international mobility challenges identity development in adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escott-Stump, S. Nutrition and Diagnosis-Related Care, 6th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Daddis, C. Desire for increased autonomy and adolescents’ perceptions of peer autonomy: “Everyone else can; why can’t I?”. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1310–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, L.M. Studying adolescence. Science 2006, 312, 1902–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.J. Development of the social brain during adolescence. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2008, 61, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, J.; Tyler, T.R. Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Soc. Justice Res. 2005, 18, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschaleri, Z.; Arabatzi, F.; Christou, E.A. Postural control in adolescent boys and girls before the age of peak height velocity: Effects of task difficulty. Gait Posture 2021, 24, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Schneider, B. Conditions for optimal development in adolescence: An experiential approach. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2001, 5, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E. Identity formation in adolescence: The dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child Dev. Persp. 2017, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R.; Johnson, M.K. Research on adolescence in the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Espnes, G.A. Self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents—gender and age as potential moderators. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aymerich, M.; Cladellas, R.; Castelló, A.; Casas, F.; Cunill, M. The evolution of life satisfaction throughout childhood and adolescence: Differences in young people’s evaluations according to age and gender. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 2347–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 66, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S.; Suldo, S.M.; Gilman, R. Life satisfaction. In Children’s Needs III: Development, Prevention, and Intervention; Bear, G.G., Minke, K.M., Eds.; National Association of School Psychologists: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 357–368. ISBN 0932955797/9780932955791. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; McBride-Chang, C.; Stewart, S.M.; Au, E. Life satisfaction, self-concept, and family relations in Chinese adolescents and children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2003, 27, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbeck, L.; Schmitz, T.G.; Besier, T.; Herschbach, P.; Henrich, G. Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.D.; Huebner, E.S.; Hills, K.J.; Van Horn, M.L. Mechanisms of change in adolescent life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suldo, S.M.; Huebner, E.S. Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 78, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Schooler, C.; Schoenbach, C.; Rosenberg, F. Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Cheung, F.M.; Bond, M.H.; Leung, J.P. Going beyond self-esteem to predict life satisfaction: The Chinese case. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 9, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, L.; Extremera, N.; Pena, M. Perceived emotional intelligence, self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents. Psychosoc. Interv. 2011, 20, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Simón Márquez, M.D.M.; Saracostti, M. Parenting practices, life satisfaction, and the role of self-esteem in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marcionetti, J.; Rossier, J. Global life satisfaction in adolescence: The role of personality traits, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. J. Individ. Differ. 2016, 37, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Diener, M. Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R.; Baumgartner, E.; Laghi, F. Social anxiety and peer communication quality during adolescence: The interaction of social avoidance, empathic concern and perspective taking. Child Youth Care Forum 2020, 49, 853–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; PallinI, S.; Baumgartner, E.; Guarino, A.; Baiocco, R. Parent and peer attachment relationships and time perspective in adolescence: Are they related to satisfaction with life? Time Soc. 2016, 25, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelienė, T. Links of adolescents identity development and relationship with peers: A systematic literature review. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Boneva, B.; Quinn, A.; Kraut, R.; Kiesler, S.; Shklovski, I. Teenage communication in the instant messaging era. In Computers, Phones and the Internet: Domesticating Information Technology; Kraut, R., Brynin, M., Kiesler, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 201–218. ISBN 139780195179637. [Google Scholar]

- Branwhite, T. Helping Adolescents in School; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 2000; ISBN 0275968987. [Google Scholar]

- Smahel, D.; Brown, B.B.; Blinka, L. Associations between online friendship and Internet addiction among adolescents and emerging adults. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr, M.; Håkan, S.; Biesecker, G.; Ferrer-Wreder, L. Relationships with parents and peers in adolescence. In Handbook of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 6, pp. 395–419. ISBN 0471384054. [Google Scholar]

- Tomé, G.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Simões, C.; Camacho, I.; AlvesDiniz, J. How can peer group influence the behavior of adolescents: Explanatory model. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manago, A.; Brown, G.; Lawley, K.; Anderson, G. Adolescent’s daily face-to-face and computer-mediated communication: Associations with autonomy and closeness to parents and friends. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 56, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poudel, A.; Gurung, B.; Khanal, G.P. Perceived social support and psychological wellbeing among Nepalese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Schooler, C.; Schoenbach, C. Self-esteem and adolescent problems: Modeling reciprocal effects. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1989, 54, 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, D.J.; Carlo, G.; Roesch, S.C. Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviors. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeus, A.; Beullens, K.; Eggermont, S. Like me (please?): Connecting online self-presentation to pre- and early adolescents’ self-esteem. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 2386–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, C. Adolescent self-esteem and social adaptation: Chain mediation of peer trust and perceived social support. Soc. Behav. Persy. 2019, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, K.G.; Meyer, L.; Schwartz, J. Effects of gender, target’s gender, topic, and self-esteem on disclosure to best and midling friends. Sex Roles 1991, 25, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.; Hendrick, S.S. Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fallah, N. Willingness to communicate in English, communication self-confidence, motivation, shyness and teacher immediacy among Iranian English-major undergraduates: A structural equation modeling approach. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 30, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D. Variables underlying willingness to communicate: A causal analysis. Commun. Res. Rep. 1994, 11, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Hu, T.; Pan, Y. The relationship between psychological Suzhi and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem and sense of security. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2018, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, S.; Smorti, M.; Tani, F. Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.Q.; Huebner, E.S. Attachment relationship and adolescents’ life satisfaction: Some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska-Cieślik, M.; Mazur, J.; Nałęcz, H.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A. Social and behavioral predictors of adolescents’ positive attitude towards life and self. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piko, B.F.; Hamvai, C. Parent, school and peer-related correlates of adolescents’ life satisfaction. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 1479–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, G.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Camacho, I.; Simões, C.; Diniz, J.A. Portuguese adolescents: The importance of parents and peer groups in positive health. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klemera, E.; Brooks, F.M.; Chester, K.L.; Magnusson, J.; Spencer, N. Self-harm in adolescence: Protective health assets in the family, school and community. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilt, L.M.; Cha, C.B.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Nonsuicidal self-injury adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.B.; Nagle, R.J. The influence of parent and peer attachments on life satisfaction in middle childhood and early adolescence. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 66, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.; Taylor, M. Positive interpersonal relationships mediate the association between social skills and psychological well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, B.M.; Webster, A.A.; Westerveld, M.F. A systematic review of school-based interventions targeting social communication behaviors for students with autism. Autism 2018, 23, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, R.W.; Seehuus, M. Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. J. Adolesc. 2019, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, S.; Joshi, H.L. Happiness in relation to social skills and self-esteem among youths. IJHW 2013, 4, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.M. Michel Hersen and the development of social skills training: Historical perspective of an academic scholar and pioneer. Behav. Modif. 2012, 36, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, M.P.; Branje, S.; Keijsers, L.; Hawk, S.T.; Hale, W.W.; Meeus, W. Self-concept clarity across adolescence: Longitudinal associations with open communication with parents and internalizing symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1861–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, V.S.Y.; Bond, M.H.; Singelis, T.M. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.M.; Zawadzka, A. Subjective well-being and citizenship dimensions according to individualism and collectivism beliefs among Polish adolescents. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2016, 4, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Germani, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Li, J.B.; Lis, A.; Nartova-Bochaver, S.K.; Vazsonyi, A.T.; Mazzeschi, C. The link between individualism-collectivism and life satisfaction among emerging adults from four countries. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021, 13, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and Adolescent Self-Image; Wesleyan University: Middletown, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri, G.; Vecchione, M.; Eisenberg, N.; Łaguna, M. On the factor structure of the Rosenberg (1965) General Self-Esteem Scale. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łaguna, M.; Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K.; Dzwonkowska, I. Skala Samooceny SES Morrisa Rosenberga—Polska adaptacja metody. Psychol. Społ. 2007, 2, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; PTP: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napora, E. Skala Komunikowania się Adolescentów z Rówieśnikami (SKAR)—Właściwości psychometryczne narzędzia szacującego zadowolenie z relacji z rówieśnikami. Pol. Forum Psychol. 2019, 24, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L.F. Statistical Analyses for Language Assessment; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock “n” Roll, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Birndorf, S.; Ryan, S.; Auinger, P.; Aten, M. High self-esteem among adolescents: Longitudinal trends, sex differences, and protective factors. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 37, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachman, J.G.; O’Malley, P.M.; Freedman-Doan, P.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Donnellan, M.B. Adolescent self-esteem: Differences by race/ethnicity, gender, and age. Self Identity 2011, 10, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canary, D.J.; Hause, K.S. Is there any reason to research sex differences in communication? Comm. Q. 1993, 41, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Thompson, R.A.; Ferrer, E. Attachment and self-evaluation in Chinese adolescents: Age and gender differences. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 1267–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A review of sex differences in peer relationship process: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strough, J.; Berg, C.A. Goals as a mediator of gender differences in high-affiliation dyadic conversations. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill, J.F. Interpreting the magnitude of correlation coefficients. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldsmith, A.H.; Veum, J.R.; Darity, W., Jr. Unemployment, joblessness, psychological well-being and self-esteem: Theory and evidence. J. Soc. Econ. 1997, 26, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, A.E.; Fend, H.A.; Allemand, M. Testing the vulnerability and scar models of self-esteem and depressive symptoms from adolescence to middle adulthood and across generations. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kapıkıran, Ş. Loneliness and life satisfaction in Turkish early adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, J.K.; Warren, M.T. Comparing adolescent positive affect and self-esteem as precursors to adult self-esteem and life satisfaction. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, V.P.; McCroskey, J.C.; McCroskey, L.L. An investigation of self-perceived communication competence and personality orientations. Commun. Res. Rep. 1989, 6, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P.; Daly, J.A.; Falcione, R.L. Studies of the relationship between communication apprehension and self-esteem. Hum. Commun. Res. 1977, 3, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Widjaja, A.E.; Yen, D.C. Need for affiliation, need for popularity, self-esteem, and the moderating effect of Big Five personality traits affecting individuals’ self-disclosure on Facebook. Int. J. Hum. Comput Int. 2015, 31, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.C.; Child, J.T.; DeGreeff, B.L.; Semlak, J.L.; Burnett, A. The influence of biological sex, self-esteem, and communication apprehension on unwillingness to communicate. Atl. J. Comm. 2011, 19, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Beer, J.S. How self-evaluations relate to being liked by others: Integrating sociometer and attachment perspectives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, M.A.; Orth, U. The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Moon, H.; Yoo, J.P.; Nam, E. How do time use and social relationships affect the life satisfaction trajectory of Korean adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lau, M.; Bradshaw, J. Material well-being, social relationships and children’s overall life satisfaction in Hong Kong. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 11, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, B.; Mayer, B.; Trommsdorff, G.; Ben-Arieh, A.; Friedlmeier, M.; Lubiewska, K.; Mishra, R.; Peltzer, K. Does the importance of parent and peer relationships for adolescents’ life satisfaction vary across cultures? J. Early Adolesc. 2012, 32, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Ozkaya, E.; LaRose, R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, V.P.; Roach, K.D. Willingness to communicate and employee success in U.S. organizations. J. Appl. Comm. Res. 1992, 20, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Feng, S. The effect of social communication on life satisfaction among the rural elderly: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salimi, A. Social-emotional loneliness and life satisfaction. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez Escoda, N.P.; Alegre, A. Does emotional intelligence moderate the relationship between satisfaction in specific domains and life satisfaction? Int. I. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2016, 16, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Yuan, R. Why do people with high dispositional gratitude tend to experience high life satisfaction? A broaden-and-build theory perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 22, 2485–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, M.; Wang, W.; Sun, G.; Cheng, Z. The influence of grit on life satisfaction: Self-esteem as a mediator. Psychol. Belg. 2018, 58, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | 27.34 | 6.42 | −0.205 | −0.507 |

| Life satisfaction | 19.37 | 6.09 | 0.012 | −0.553 |

| Openness | 37.10 | 7.34 | −0.414 | −0.420 |

| Difficulty | 25.21 | 6.07 | 0.012 | −0.259 |

| Scales | Self-Esteem | Life Satisfaction | Openness | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | 1 | |||

| Life satisfaction | 0.64 *** | 1 | ||

| Openness | 0.30 *** | 0.33 *** | 1 | |

| Difficulty | −0.23 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.49 *** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szcześniak, M.; Bajkowska, I.; Czaprowska, A.; Sileńska, A. Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction: Communication with Peers as a Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073777

Szcześniak M, Bajkowska I, Czaprowska A, Sileńska A. Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction: Communication with Peers as a Mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073777

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzcześniak, Małgorzata, Iga Bajkowska, Anna Czaprowska, and Aleksandra Sileńska. 2022. "Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction: Communication with Peers as a Mediator" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073777

APA StyleSzcześniak, M., Bajkowska, I., Czaprowska, A., & Sileńska, A. (2022). Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction: Communication with Peers as a Mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073777