The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- To describe the role and use of the Bolk model in the development and implementation of an integrated health promotion approach in Amsterdam SE.

- (ii)

- To describe the experiences and perceptions of residents and other stakeholders in the community where this model has been implemented.

- (iii)

- To explore whether a cultural transformation had occurred from “disease management thinking” towards “Positive Health thinking” and towards better collaboration among stakeholders in Amsterdam SE.

2. Methods

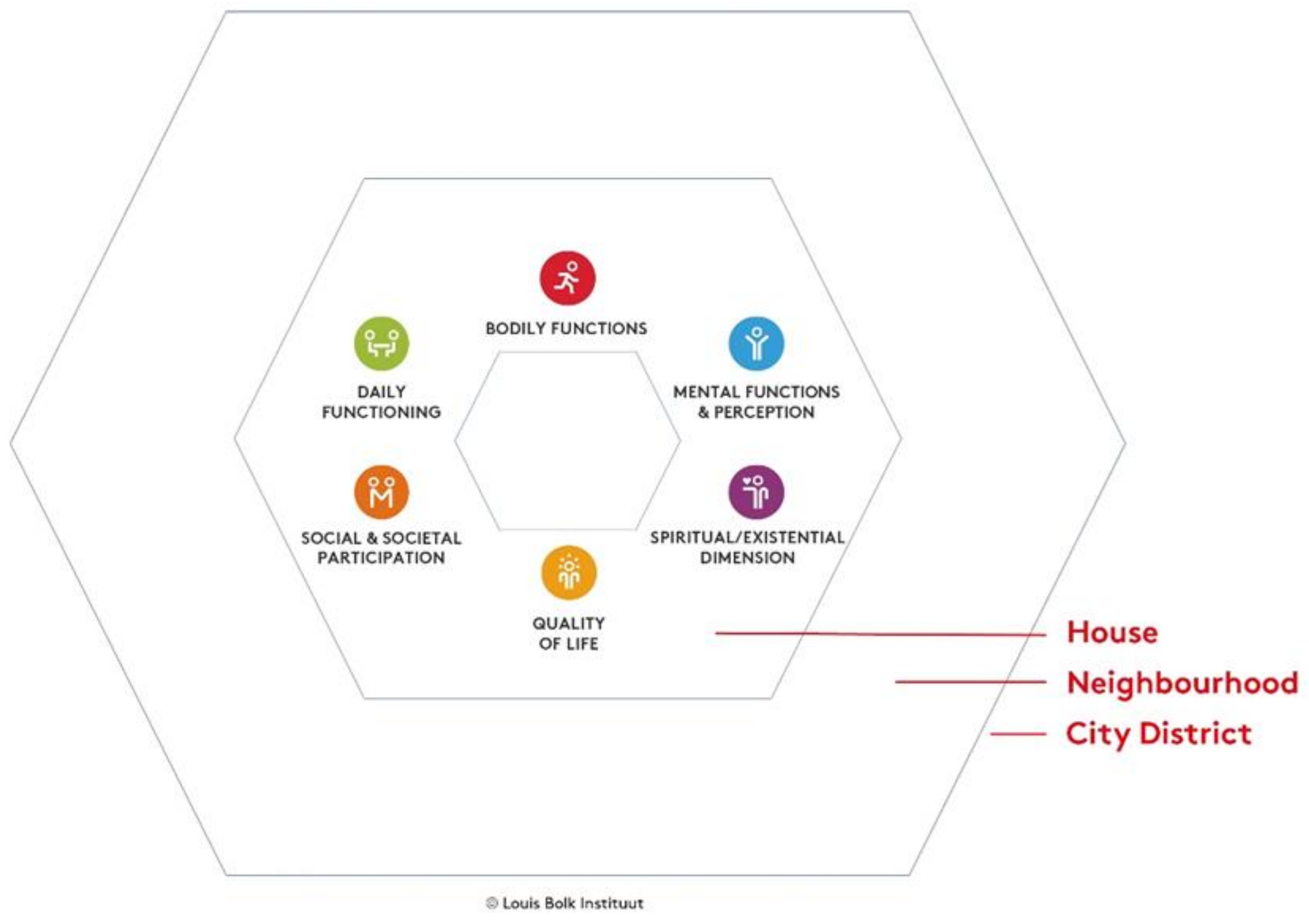

2.1. The Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment

2.2. Case Study—Setting

2.3. Case Study—Design

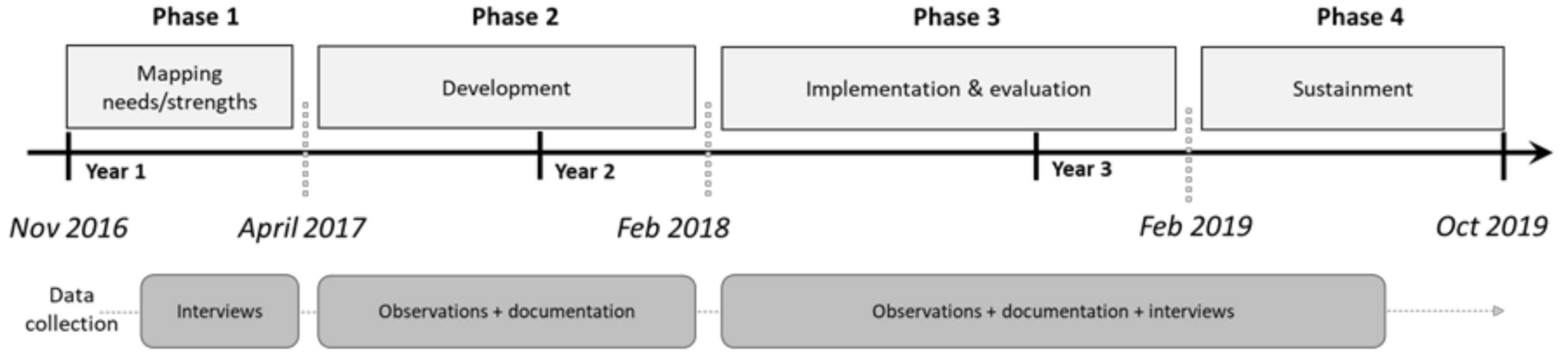

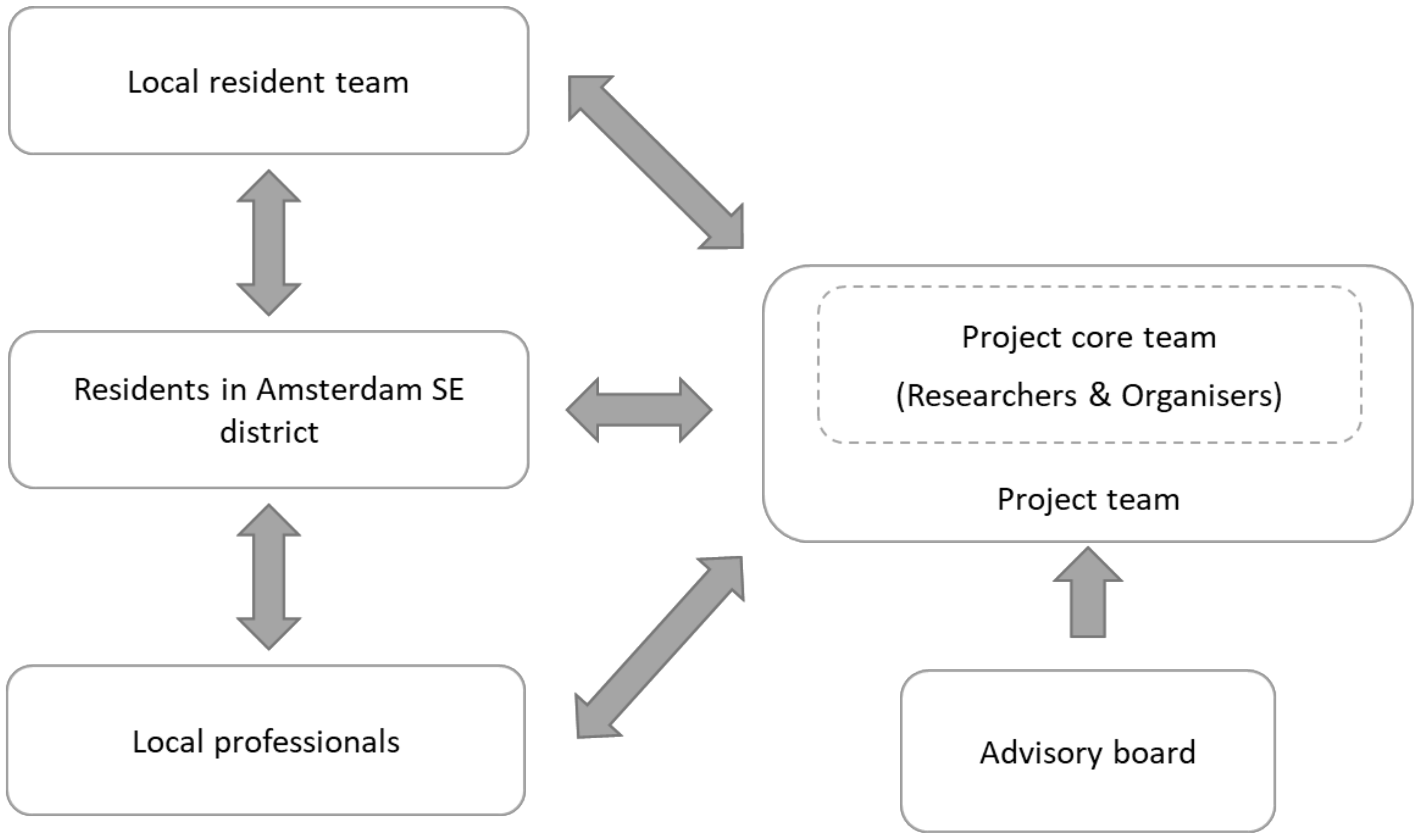

2.4. Case Study—Participatory Approach

2.4.1. Phase 1: Mapping Needs and Strengths of Residents in the Amsterdam South East District

2.4.2. Phase 2: Development of the Integrated Health Promotion Approach

2.4.3. Phase 3: Implementation and Evaluation of the Integrated Health Promotion Approach

2.4.4. Phase 4: Sustainment of the Integrated Health Promotion Approach

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. The Role and Use of the Bolk Model in the Development and Implementation of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach

3.1.1. Identifying Needs and Strengths of Residents of Residents by Means of the Bolk Model (Phase 1)

Appearance of the Neighborhood

Resident 1: “If you look outside and the weather is dark, you get dark yourself. But if the doors are closed and the windows are closed and the flowers and trees are nice and green, that makes me happy, it makes me smile. And then you go outside much happier.”

Social Cohesion

Resident 2: “I think people meet each other in community centers and there is a street culture here. Many people chat with each other on the street. At Multibron [read: a community center] we have a lot of accessible activities such as a chat hour.”

Resident 3: “I always make contact with everyone. When I go out in the street, I say: good morning, good day.”

Help and Care

Resident 4: “It is so nice that there are parents that are really “the help parents” in the school, they are like the mother of your child at that moment. If there is something [read: that they know about your child], and they know you or they know another mother, then it reaches you, (…) because you don’t always hear everything from the teacher.”

Knowledge and Self-Development

Resident 4: “You should work with the parents. Health can only be improved if you can get parents to change their mind setting as awareness of what is in the food products, how do I prepare it, how much do I eat, how do I balance it throughout the day and how do I combine it with exercise and how do I communicate my limits to my children.”

Organizations and Services in the Neighborhood

3.1.2. Mapping Needs and Strengths of Residents Using the Bolk Model (Phase 1)

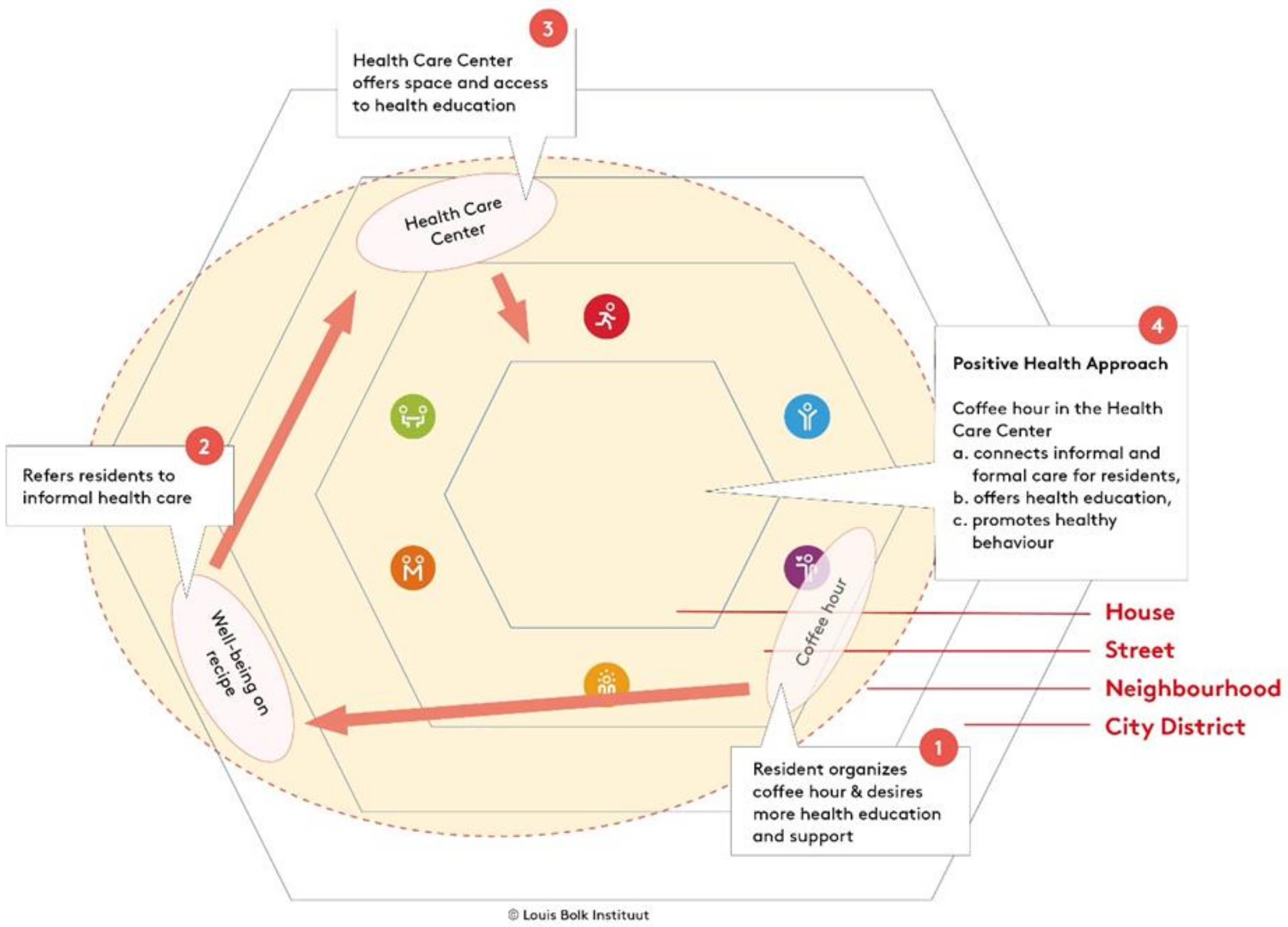

3.1.3. Development of Health Promotion Pilots (HPPs) by Means of the Bolk Model (Phase 2)

3.1.4. Implementation of the HPPs by Means of the Bolk Model (Phase 3)

3.2. Experiences and Perceptions of Residents and Other Stakeholders in the Community of Working with the Bolk Model (Phase 3)

3.2.1. Understanding of Positive Health

Resident 9: “I do not know, maybe I do not understand [PH], maybe others do. I think [it is] a little bit difficult.”

3.2.2. Acceptance of Positive Health

Resident 14: “Yes, I think it can [PH to bring change in Venserpolder], it makes you more conscious of the choices you can make to be more positive or aware of your neighborhood or with yourself.”

3.2.3. Integration of Positive Health in Thinking and Behavior

Professional 2: “I have to say, the research, for me personally it was an eye opener. Health is not just health; it is also wellbeing.”

3.3. The Process of Cultural Transformation from “Disease Management Thinking” towards “Positive Health Thinking” and towards Better Collaboration among Stakeholders in Amsterdam SE (Phase 3 and 4)

3.3.1. Urgency

Professional 1: “People live seven years shorter, and the quality of healthy living is fourteen years shorter I believe. Well, you do not need more reasons I think.”

3.3.2. Guiding Coalition

Researcher 1: “Yes I think one of the powers [PH] is that it creates connections between different organizations and stakeholders. The people feel seen, that they all form part of the solution and that the resident is central.”

3.3.3. Change Vision and Communicating the Change Vision

Project coordinator 1: “The system world speaks a different language than the target group whom it concerns. The communication has to be target-bound, the information that is made public should be accessible for everyone.”

3.3.4. Barriers and Enabling Factors

Resident 15: “… The communication they [the project team] have with residents [is specifically good about this project in comparison to other projects], to involve residents and that they can take initiative to organize things and create workshops, etc.”

3.3.5. Sustainability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mackenbach, J.; Stronks, K. Volksgezondheidszorg en Gezondheidszorg [Public Health and Healthcare]; Reed Business: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Van Vuuren, C.L.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van der Wal, M.F.; Verhoeff, A.P. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation characteristics in child (0–18 years) health studies: A review. Heal. Place 2014, 29, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Kulhánová, I.; Artnik, B.; Bopp, M.; Borrell, C.; Clemens, T.; Costa, G.; Dibben, C.; Kalediene, R.; Lundberg, O.; et al. Changes in mortality inequalities over two decades: Register based study of European countries. BMJ 2016, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Broeders, D.; Das, D.; Jennissen, R.; Tiemeijer, W.; Visser de, M. Van verschil naar potentieel Een realistisch perspectief op de sociaaleconomische gezondheidsverschillen. WRR Policy Br. 2018, 46, pp. 2–14.

- GGD Amsterdam. Zuidoost Gezond en Wel? Factsheet Amsterdamse Gezondheidsmonitor 2012; Is the South-East Amsterdam Healthy and Happy? Factsheet Amsterdam Health Monitor. Amsterdam. 2014. Available online: https://www.ggdgezondheidinbeeld.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/gib_amsterdam_volwassenen_in_zuidoost_2012.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Van Vuuren, C.L.; Verhagen, C.; van der Wal, M. Hoe Gezond Zijn Jongeren in Zuidoost. How Healthy is the Youth Living in South East Amsterdam. In Epidemiology & Gezondheidsbevordering/Jeugdgezondheidszorg; GGD Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, C.E.; Buster, M.C.A. Sterk en Zwak in Amsterdam: Een analyse van 11 leefdomeinen in 22 Amsterdamse gebieden. In Strong and Weak in Amsterdam: An Analysis of 11 Life Domains in 22 Areas in Amsterdam; GGD Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Droomers, M.; Harting, J.; Jongeneel-Grimen, B.; Rutten, L.; van Kats, J.; Stronks, K. Area-based interventions to ameliorate deprived Dutch neighborhoods in practice: Does the Dutch District Approach address the social determinants of health to such an extent that future health impacts may be expected? Prev. Med. 2014, 61, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droomers, M.; Jongeneel-Grimen, B.; Kramer, D.; de Vries, S.; Kremers, S.; Bruggink, J.-W.; van Oers, H.; Kunst, A.E.; Stronks, K. The impact of intervening in green space in Dutch deprived neighbourhoods on physical activity and general health: Results from the quasi-experimental URBAN40 study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Dieren, L.; Steenkamer, I. Kinderen in Zuid Gezond en Wel? Children in the South of The Netherlands Healthy and Happy? GGD Amsterdam, Epidemiology & Gezondheidsbevordering: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.C.; Winpenny, E.; Ball, S.; Fowler, T.; Rubin, J.; Nolte, E. For debate: A new wave in public health improvement. Lancet 2014, 384, 1889–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, J.; Jones, R.; Stansfield, J.; Bagnali, A.-M. What Quantitative and Qualitative Methods Have Been Developed to Measure Health-Related Community Resilience at a National and Local Level? 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30484993 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- WHO. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lucyk, K.; McLaren, L. Taking stock of the social determinants of health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F.; Floyd, M.F.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Saelens, B.E. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Van Den Berg, M.M.H.E. Health benefits of plants and green space: Establishing the evidence base. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1093, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Green, L.; Horst, H.V.D.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; Meer, J.W.M.V.D.; et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huber, M.; van Vliet, M.; Giezenberg, M.; Winkens, B.; Heerkens, Y.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Knottnerus, J.A. Towards a “patient-centred” operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Steekelenburg, E.; Kersten, I. ‘Positieve Gezondheid’ in Nederland; Institute for Positive Health: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MinVWS. Gezondheid Breed op de Agenda; [General Health on the Agenda]; MinVWS: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Lemmens, L.; de Bruin, S.; Beijer, M.; Hendrikx, R.; Baan, C. Het Gebruik van Brede Gezondheidsconcepten: Inspirerend en Uitdagend Voor de Praktijk. The Use of Broad Health Concepts: Inspiring and Challeging to Put into Practice. RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians; Department of Supply and Services: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1974. Available online: https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/pdf/perspect-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- GGD. Monitor Gezondheid Health Monitor. Available online: http://www.monitorgezondheid.nl (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Grandy, G. Instrumental Case Study. In Encyclopaedia of Case Study Research; Mills, A., Durepos, G., Wiebe, E., Eds.; SAGE Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 474–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hoes, A.; Regeer, B.; Bunders, J. Facilitating Learning in Innovative Projects: Reflections on our experiences with ILA-monitoring. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Organizational Learning, Knowledge and Capabilities OLKC; Northeastern University: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L.; Ellström, L.; Brulin, P.-E. Introduction-on interactive research. Int. J. Action Res. 2007, 3, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research: Observational methods in health care settings. BMJ 1995, 311, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.J.; Spencer, R.A.; Shrestha, B.; Ferguson, G.; Oakes, J.M.; Gupta, J. Evaluating a multicomponent social behaviour change communication strategy to reduce intimate partner violence among married couples: Study protocol for a cluster randomized trial in Nepal. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conner, D.; Patterson, R. Building commitment to organizational change. Train. Dev. J. 1982, 36, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt, J. ADKAR: A Model for Change in Business, Government and Our Community; Prosci Learning Center Publications: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MDRC Applying Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Promote Positive Change. Available online: https://www.mdrc.org/publication/applying-cognitive-behavioral-therapy-promote-positive-change (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Kotter, J. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, S.F.; Luke, D.A.; Schooley, M.W.; Elliott, M.B.; Herbers, S.H.; Mueller, N.B.; Bunger, A.C. Public health program capacity for sustainability: A new framework. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranney, M.L.; Griffeth, V.; Jha, A.K. Social Prescribing—Transforming the Relationship between Physicians and Their Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1969–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, E.R.; Dombrowski, S.U.; McCleary, N.; Johnston, M. Are interventions for low-income groups effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Translating Social Ecological Theory Into. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nickel, S.; von dem Knesebeck, O. Effectiveness of Community-Based Health Promotion Interventions in Urban Areas: A Systematic Review. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husk, K.; Elston, J.; Gradinger, F.; Callaghan, L.; Asthana, S. Social prescribing: Where is the evidence? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pescheny, J.V.; Randhawa, G.; Pappas, Y. The impact of social prescribing services on service users: A systematic review of the evidence. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boers, I.; Huber, M. Hoe Krijgt het Concept Positieve Gezondheid Regionaal Handen en Voeten? [How Does the Concept of Positive Health become Established in a Region?]; Louis Bolk Institute: Driebergen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GGD Amsterdam. Gezondheid en Welbevinden in Amsterdam Kernpunten [Health and Wellbeing in Amsterdam]; GGD: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shilton, T.; Sparks, M.; McQueen, D.; Lamarre, M.C.; Jackson, S. How should we define health? Proposal for new definition of health. BMJ 2011, 343, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in context. Online readings. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Acosta, J.; Meredith, L.; Sanches, K.; Howard, S.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Williams, M.; Yeung, D. Understanding Community Resilience in the Context of National Health Security: A Literature Review. RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winderl, T.; Whittaker, J.; Handmer, J.; Mclennan, B.; United Nations Volunteers; United Nations Deveopment Programme; United Nations Development Programme; Un-Isdr; UNDP (United Nations Development Programme); UNDP Drylands Development Centre; et al. IFRC framework for community resilience. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Pilot | Expected Result | Target Group |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Coffee hour in health care center | Informal talk about health and social support, improved access of health care professionals to residents | Residents Venserpolder |

| 2. Digital connecting | Digital map of informal care options and social activities available in the library | Residents Amsterdam South East |

| 3. Healthy shopping area | More healthy products in shops in the local shopping area | Residents Venserpolder |

| 4. Green and health workshops | Vegetable gardening workshops, | Women Venserpolder |

| 5. Healthy eating for kids | Teaching children food preparation and healthy eating | Children Venserpolder |

| 6. Man power | More activities for men | Men Venserpolder |

| 7. Accessibility | Better access to streets and buildings for people with special needs | Residents with special needs |

| 8. Thematic health events | Knowledge sharing about health and personal development | Residents Venserpolder |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Wietmarschen, H.A.; Staps, S.; Meijer, J.; Flinterman, J.F.; Jong, M.C. The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042478

van Wietmarschen HA, Staps S, Meijer J, Flinterman JF, Jong MC. The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042478

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Wietmarschen, Herman A., Sjef Staps, Judith Meijer, J. Francisca Flinterman, and Miek C. Jong. 2022. "The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042478

APA Stylevan Wietmarschen, H. A., Staps, S., Meijer, J., Flinterman, J. F., & Jong, M. C. (2022). The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042478