Social Health among German Nursing Home Residents with Dementia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Role of Technology to Promote Social Participation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Has there been an observable change in the clinical conditions of nursing home residents with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the availability of social activities for nursing home residents with dementia?

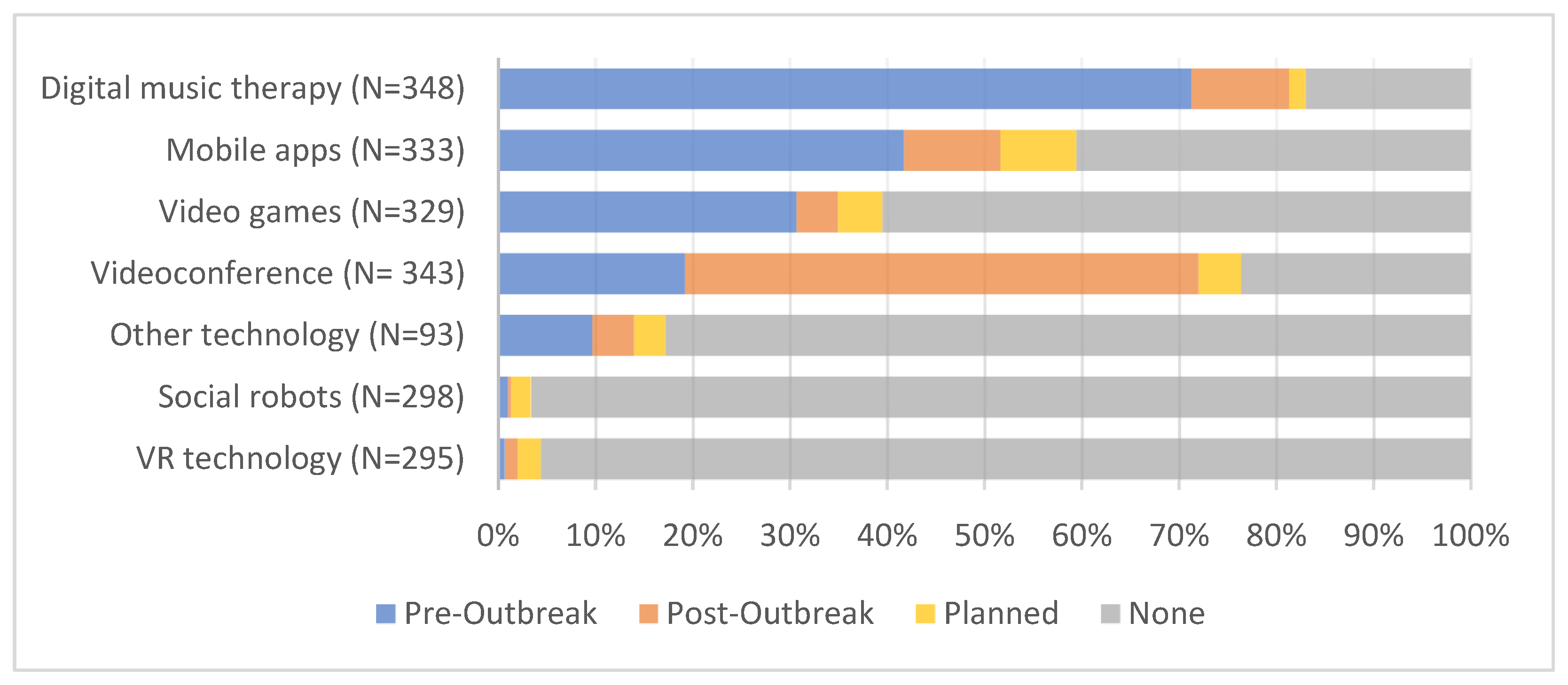

- How has technology played a role in ensuring social participation for nursing home residents?

- What barriers and facilitators exist for people in need of care to use digital technologies for social participation?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Processing and Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Clinical Conditions

3.3. Social Activities for People Living with Dementia during COVID-19

3.4. Promoting Social Participation for People Living with Dementia Using Technology

3.5. Qualitative Findings

3.5.1. Micro-Level: Care Recipient

“On average, they should be 30 years younger and open to digital technologies. They will be in 30 years.”(id_401)

“They should have the ability to handle it. The currently cared-for seniors have not learned how to deal with today’s technologies, and most of them are not even willing to learn how to use them—they feel overwhelmed. It is still an absolute minority that uses digital technologies. Only the next generation of seniors will use digital technology because they are already using it today.”(id_1182)

“For people with dementia who live alone in their homes, I’m rather skeptical about such digital technologies because they have a view of the world that lies in the past. So, it would shake their worldview and also their self-image because it simply doesn’t fit into their world. Such technologies would only make sense if they were used together with caregivers.”(id_482)

3.5.2. Meso-Level: Organizational Requirements

“Contact persons and people in charge who accompany the organization, administration and implementation, since nursing staff have too little time and knowledge of possible technologies and their application. For many clients, staff must be present during the entire period of use to provide support, which everyday life does not allow.”(id_337)

“Education (to take away the anxiety), instruction and accompaniment until the technology can either be safely operated by the user or an everyday helper who can provide support.”(id_1148)

“It would be great to have at least one additional job position in each nursing service/nursing home, financed through the nursing tariffs. This position should be specifically responsible for digital technologies and be able to train customers and employees. Overall, the introduction of the technologies would have to be supported more. We don’t get it done here because there is too little time left for it.”(id_195)

3.5.3. Macro-Level: Policy and Legislation

“Secure communication channels, adequately fast and cheap internet, adequate equipment, possibly free Wi-Fi should be considered, additional rights to tablets for seniors with basic income support or welfare benefits.”(id_379)

“Low-cost devices or cost support from health or long-term care insurers. Telecommunications providers must expand their offerings to explain and install this technology on-site. This responsibility must not be shifted to care employees.”(id_1246)

3.5.4. Technology Requirements

“The technology must be available on site (Wi-Fi, laptop, camera, etc.), […], physical limitations must be taken into account (paralysis, etc.), the monitor must be large, and all buttons must be large and clearly arranged, possibly a voice assistant.”(id_1093)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, E.E.; Kumar, S.; Rajji, T.K.; Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H. Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canevelli, M.; Bruno, G.; Cesari, M. Providing Simultaneous COVID-19-sensitive and Dementia-Sensitive Care as We Transition from Crisis Care to Ongoing Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 968–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devita, M.; Bordignon, A.; Sergi, G.; Coin, A. The psychological and cognitive impact of COVID-19 on individuals with neurocognitive impairments: Research topics and remote intervention proposals. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Amiri, A.; Morovatdar, N.; Steinwender, S.; Rezaei Ardani, A.; Yassi, N.; Biller, J.; Stranges, S.; Tokazebani Belasi, M.; Neya, S.K.; et al. Correlations between COVID-19 and burden of dementia: An ecological study and review of literature. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 416, 117013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F.S.; Wallace, T.; Luszcz, M.A.; Reynolds, K.J. Usability of Tablet Computers by People with Early-Stage Dementia. Gerontology 2013, 59, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2009; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti, A.; Pais, C.; Jones, M.; Cipriani, M.C.; Janiri, D.; Monti, L.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Liperoti, R.; Sani, G. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Elderly With Dementia During COVID-19 Pandemic: Definition, Treatment, and Future Directions. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.Y.; Schwartz, J.; King, C.C.; Lee, C.M.; Hsueh, P.R. Recommendations for protecting against and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care facilities. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Ouslander, J.G. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Geriatrics and Long-Term Care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drupp, M.; Meyer, M.; Winter, W. Betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement (BGM) für Pflegeeinrichtungen und Krankenhäuser unter Pandemiebedingungen. In Pflege-Report 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Schmidt, A.; Preuß, B.; Heinze, F.; Seibert, K.; Friedrich, A.C.; Domhoff, D.; Stolle, C.; Rothgang, H. Care in times of Corona: Results of a cross-sectional study in German home care services. Pflege 2020, 33, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, A.; Bellelli, G.; Guerini, F.; Marengoni, A.; Padovani, A.; Rozzini, R.; Trabucchi, M. Improving the care of older patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouslander, J.G.; Grabowski, D.C. COVID-19 in Nursing Homes: Calming the Perfect Storm. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padala, S.P.; Jendro, A.M.; Orr, L.C. Facetime to reduce behavioral problems in a nursing home resident with Alzheimer’s dementia during COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 113028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, L.; Aarsland, D.; Ballard, C. Mental health of people living with dementia in care homes during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1253–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Gerritsen, D.L.; Backhaus, R.; de Boer, B.S.; Koopmans, R.T.C.M.; Hamers, J.P.H. Allowing Visitors Back in the Nursing Home During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Dutch National Study Into First Experiences and Impact on Well-Being. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, S.H.; Beck, C.; Hong, S.H. Feasibility of providing computer activities for nursing home residents with dementia. Non-Pharmacol. Ther. Dement. 2013, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski, A.; Litaker, M. Social interaction, premorbid personality, and agitation in nursing home residents with dementia. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2006, 20, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Marx, M.S.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Regier, N.G.; Thein, K.; Freedman, L. Can Agitated Behavior of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia Be Prevented with the Use of Standardized Stimuli? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper Ice, G. Daily life in a nursing home: Has it changed in 25 years? J. Aging Stud. 2002, 16, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. MDS Active Resident Information Report: Third Quarter 2010. Available online: https://www.cms.gov (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Kang, H. Correlates of social engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tak, S.H.; Kedia, S.; Tongumpun, T.M.; Hong, S.H. Activity engagement: Perspectives from nursing home residents with dementia. Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Green, L.; van der Horst, H.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dröes, R.M.; Chattat, R.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Graff, M.; Murphy, K.; Verbeek, H.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Clare, L.; Johannessen, A.; et al. Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vugt, M.; Dröes, R.-M. Social health in dementia. Towards a positive dementia discourse. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. The impact of group activities and their content on persons with dementia attending them. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Vasse, E.; Zuidema, S.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Moyle, W. Psychosocial interventions in dementia care in long term care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orsulic-Jeras, S.; Judge, K.S.; Camp, C.J. Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents with advanced dementia: Effects on engagement and affect. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T.M. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haitsma, K.S.; Curyto, K.; Abbott, K.M.; Towsley, G.L.; Spector, A.; Kleban, M. A randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, S.I.; e Silva, J.C.; Cohen, G.; Miller, S.; Sartorius, N. Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: A consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1996, 8, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, A.; Litaker, M.; Buettner, L.; Moeller, J.; Costa, J.; Paul, T. A randomized clinical trial of theory-based activities for the behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jøranson, N.; Pedersen, I.; Rokstad, A.M.M.; Ihlebæk, C. Effects on Symptoms of Agitation and Depression in Persons With Dementia Participating in Robot-Assisted Activity: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyle, W.; Bramble, M.; Jones, C.J.; Murfield, J.E. “She had a smile on her face as wide as the Great Australian Bite”: A qualitative examination of family perceptions of a therapeutic robot and a plush toy. Spec. Issue Technol. Aging Evolv. Partnersh. 2019, 59, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossey, J.; Ballard, C.; Juszczak, E.; James, I.; Alder, N.; Jacoby, R.; Howard, R. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ballard, C.; Corbett, A. Agitation and aggression in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2013, 26, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerens, H.C.; de Boer, B.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Tan, F.E.S.; Ruwaard, D.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Verbeek, H. The association between aspects of daily life and quality of life of people with dementia living in long-term care facilities: A momentary assessment study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, K.; Beer, E.; Eppingstall, B.; O’Connor, D.W. A comparison of two treatments of agitated behavior in nursing home residents with dementia: Simulated family presence and preferred music. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Fisher, J.; Segal, G. Characterization and effectivenes of family-generated videotape for the management of VDB. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2000, 19, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camberg, L.; Woods, P.; Ooi, W.L.; Hurley, A.; Volicer, L.; Ashley, J.; Odenheimer, G.; McIntyre, K. Evaluation of Simulated Presence: A personalized approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgang, H.; Domhoff, D.; Friedrich, A.-C.; Heinze, F.; Preuß, B.; Schmidt, A.; Seibert, K.; Stolle, C.; Wolf-Ostermann, K. Pflege in Zeiten von Corona: Zentrale Ergebnisse einer deutschlandweiten Querschnitts befragung vollstationärer Pflegeheime Long-term care during the Corona pandemic -Main results from a nationwide online survey in nursing homes in Germany Einleitung. Pflege 2020, 33, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerejeira, J.; Lagarto, L.; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Front. Neurol. 2012, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinand, C.; Halek, M. 2 Challenges in interacting with people with dementia. In Aging between Participation and Simulation; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cloak, N.; Al Khalili, Y. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Duval, S.; Anderson, K.A.; Kane, R.L. Predicting nursing home admission in the US: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hébert, R.; Dubois, M.-F.; Wolfson, C.; Chambers, L.; Cohen, C. Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: Data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M693–M699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, E.J.; Yu, F.F.; Krichbaum, F.K.; Wyman, F.J. Predictors of Nursing Home Admission for Persons with Dementia. Med. Care 2009, 47, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Marx, M.S.; Rosenthal, A.S. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J. Gerontol. 1989, 44, M77–M84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Cooke, M.; O’Dwyer, S.; Sung, B.; Drummond, S. Connecting the person with dementia and family: A feasibility study of a telepresence robot. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koh, W.Q.; Felding, S.; Budak, B.; Toomey, E.; Casey, D. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of social robots for older adults and people with dementia: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Wagner, L.; Spetz, J. Nursing Home Implementation of Health Information Technology: Review of the Literature Finds Inadequate Investment in Preparation, Infrastructure, and Training. Inquiry 2018, 55, 0046958018778902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, V.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Ambugo, E.A. Social isolation and the use of technology in caregiving dyads living with dementia during COVID-19 restrictions. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 697496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.; van den Berg, F.; Planting, C.; Ettema, T.; Dijkstra, K.; Finnema, E.; Dröes, R.-M. Can Use of Digital Technologies by People with Dementia Improve Self-Management and Social Participation? A Systematic Review of Effect Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, H.; Parker, K.; Howard, N.; Hugo, G. New technologies: Their potential role in linking rural older people to community. Ijets 2010, 8, 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, M.V.; Scopelliti, M.; Fornara, F. Elderly people at home: Technological help in everyday activities. In Proceedings of the ROMAN 2005 IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Nashville, TN, USA, 13–15 August 2005; pp. 365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, V.; von Zweck, C.; Ledgerd, R. Was a global pandemic needed to adopt the use of telehealth in occupational therapy? Work 2020, 68, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, N. Digitalization and Political Science in Germany. In Political Science and Digitalization–Global Perspectives, 1st ed.; Kneuer, M., Milner, H.V., Eds.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2019; pp. 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Pflegestatistik, Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung Deutschlandergebnisse. 2019. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Pflege/Publikationen/Downloads-Pflege/laender-pflegeheime-5224102199004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Budak, K.B.; Atefi, G.; Hoel, V.; Laporte Uribe, F.; Meiland, F.; Teupen, S.; Felding, S.A.; Roes, M. Can technology impact loneliness in dementia? A scoping review on the role of assistive technologies in delivering psychosocial interventions in long-term care. Disabil. Rehabilit. Assist. Technol. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Bruno, A.C.; Garcia-Casal, J.A.; Csipke, E.; Jenaro-Rio, C.; Franco-Martin, M. ICT-based applications to improve social health and social participation in older adults with dementia. A systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neal, I.; du Toit, S.H.J.; Lovarini, M. The use of technology to promote meaningful engagement for adults with dementia in residential aged care: A scoping review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (N a) | N b (SD) | % c |

|---|---|---|

| Sector (N = 401) | ||

| Public | 37 | 9.2 |

| Private | 149 | 37.2 |

| Non-Profit | 215 | 53.6 |

| Special dementia care contract (N = 407) | 70 | 17.2 |

| Average no. of healthcare staff per facility (SD) (N = 366) | 48.3 (26.5) | - |

| Average client capacity per facility (SD) (N = 404) | 86.3 (41.2) | - |

| Confirmed COVID-19 cases among residents ( d) (N = 402) | 212 (21) | 52.7 |

| Confirmed COVID-19 cases among staff () (N = 402) | 281 (11) | 69.9 |

| Average no. of deaths with COVID-19 among residents (N = 139) | 7 (6.61) | - |

| Social activities canceled (N = 366) | 155 | 42.4 |

| Special access to visit residents with dementia (N = 284) | 42 | 14.8 |

| Established procedures to use technology with residents with dementia (N = 369) | 24 | 6.5 |

| Opportunities to use digital communication technology for social contact (N = 349) | 254 | 72.8 |

| Social Tech training for staff (N = 353) | ||

| None | 179 | 50.7 |

| Less than 2 h | 112 | 31.7. |

| Up to 4 h | 21 | 6.0 |

| Up to 8 h | 4 | 1.1 |

| Over days | 1 | 0.3 |

| Training is planned | 17 | 4.8 |

| Observed increase of pharmacological therapy (N = 344) | 20 | 5.8 |

| Observed increase of BPSD e (N = 373) | ||

| Aggression | 63 | 16.9 |

| Anxiety | 144 | 38.6 |

| Apathy | 60 | 16.1 |

| Appetite loss | 90 | 24.1 |

| Depression | 145 | 38.9 |

| Hallucinations | 5 | 1.3 |

| Paranoia | 2 | 0.5 |

| Psychosis | 17 | 4.6 |

| Sleeplessness | 39 | 10.5 |

| Wandering | 63 | 16.9 |

| Other | 36 | 9.7 |

| Social Activities Canceled | Total | Χ2 | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||

| type of provider | public | N | 15 | 17 | 32 | 3.5929 | 0.464 |

| % | 46.9 | 53.1 | 100 | ||||

| private | N | 47 | 81 | 128 | |||

| % | 36.7 | 63.3 | 100 | ||||

| non-profit | N | 87 | 100 | 187 | |||

| % | 46.5 | 53.5 | 100 | ||||

| total | N | 149 | 198 | 347 | |||

| % | 42.9 | 57.1 | 100 | ||||

| special dementia care contract | yes | N | 26 | 37 | 63 | 1.3689 | 0.504 |

| % | 41.3 | 58.7 | 100 | ||||

| no | N | 129 | 168 | 297 | |||

| % | 43.4 | 56.6 | 100 | ||||

| total | N | 155 | 205 | 360 | |||

| % | 43.1 | 56.9 | 100 | ||||

| cases among residents | yes | N | 93 | 98 | 191 | 7.693 | 0.021 * |

| % | 48.7 | 51.3 | 100 | ||||

| no | N | 53 | 102 | 155 | |||

| % | 34.2 | 65.8 | 100 | ||||

| total | N | 146 | 200 | 346 | |||

| % | 42.2 | 57.8 | 100 | ||||

| cases among staff | yes | N | 119 | 133 | 252 | 9.9753 | 0.007 ** |

| % | 47.2 | 52.8 | 100 | ||||

| no | N | 27 | 67 | 94 | |||

| % | 28.7 | 71.3 | 100 | ||||

| total | N | 146 | 200 | 346 | |||

| % | 42.2 | 57.8 | 100 | ||||

| >5% staff shortage | yes | N | 101 | 96 | 197 | 13.0971 | 0.001 ** |

| % | 51.3 | 48.7 | 100 | ||||

| no | N | 53 | 107 | 160 | |||

| % | 33.1 | 66.9 | 100 | ||||

| total | N | 154 | 203 | 357 | |||

| % | 43.1 | 56.9 | 100 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoel, V.; Seibert, K.; Domhoff, D.; Preuß, B.; Heinze, F.; Rothgang, H.; Wolf-Ostermann, K. Social Health among German Nursing Home Residents with Dementia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Role of Technology to Promote Social Participation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041956

Hoel V, Seibert K, Domhoff D, Preuß B, Heinze F, Rothgang H, Wolf-Ostermann K. Social Health among German Nursing Home Residents with Dementia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Role of Technology to Promote Social Participation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041956

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoel, Viktoria, Kathrin Seibert, Dominik Domhoff, Benedikt Preuß, Franziska Heinze, Heinz Rothgang, and Karin Wolf-Ostermann. 2022. "Social Health among German Nursing Home Residents with Dementia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Role of Technology to Promote Social Participation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041956

APA StyleHoel, V., Seibert, K., Domhoff, D., Preuß, B., Heinze, F., Rothgang, H., & Wolf-Ostermann, K. (2022). Social Health among German Nursing Home Residents with Dementia during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Role of Technology to Promote Social Participation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041956