In Whom Do We Trust? A Multifoci Person-Centered Perspective on Institutional Trust during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Person-Centered Approach to Trust in Government

1.2. Trust-in-Government Profiles and COVID-19 Attitudes and Compliance

1.3. Trust-in-Government Profiles and Job Insecurity

1.4. Trust-in-Government Profiles and Affective Commitment

1.5. Trust-in-Government Profiles and Helping Behavior

1.6. Trust-in-Government Profiles and Psychological Well-Being

2. Method

2.1. Participants, Procedure, and Measures

2.2. Statistical Analyses: Latent Profile Analysis (LPA)

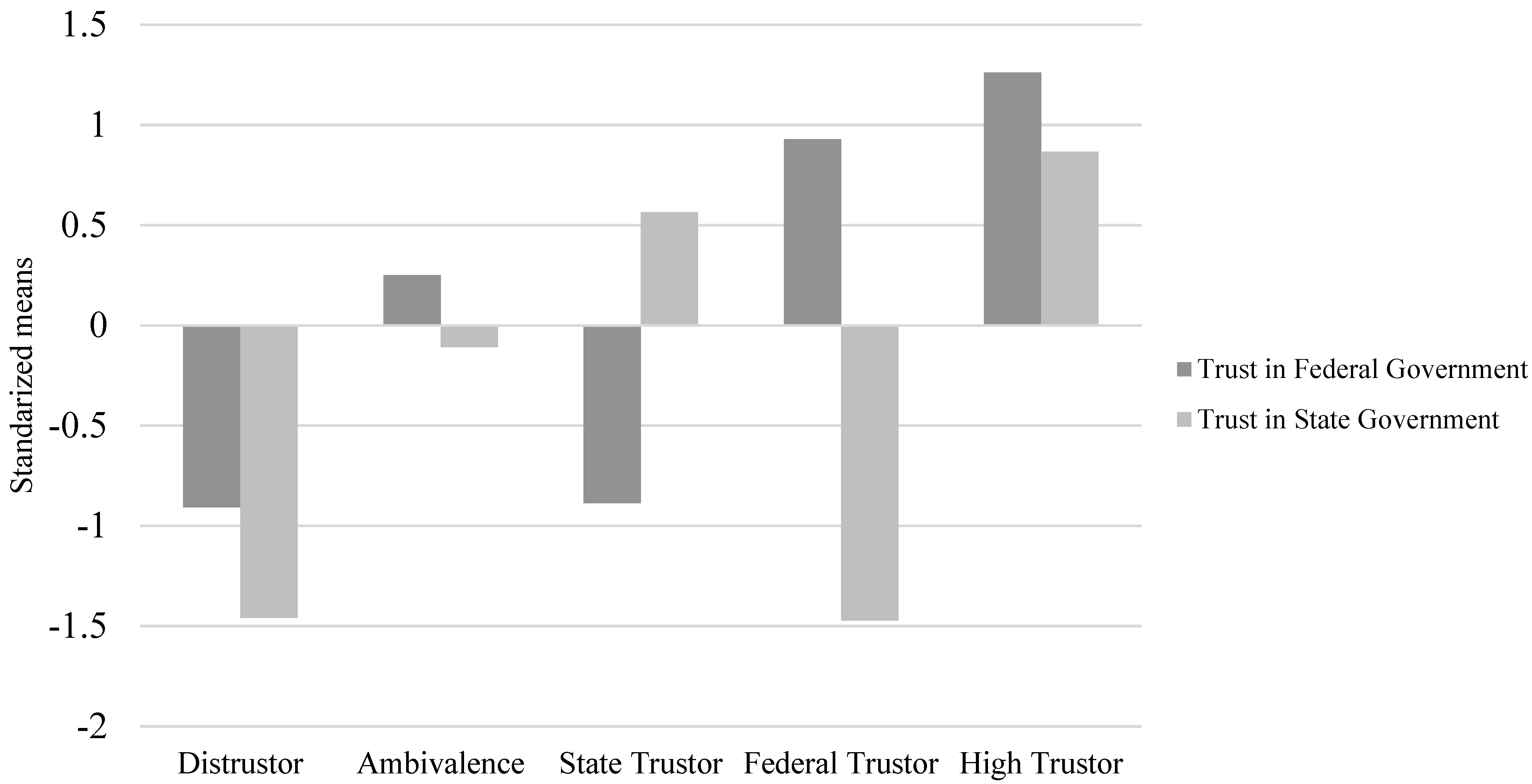

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. American’s Views of Government: Low Trust, but Some Positive Performance Ratings. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/09/14/americans-views-of-government-low-trust-but-some-positive-performance-ratings (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Tyler, T.R. Policing in black and white: Ethnic group differences in trust and confidence in the police. Police Q. 2005, 8, 322–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsloot, I.; Boin, A.; Jacobs, B.; Comfort, L.K. Mega-Crises: Understanding the Prospects, Nature, Characteristics, and the Effects of Cataclysmic Events; Charles C Thomas Publisher: Springfield, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Willer, R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangerter, A. Investigating and rebuilding public trust in preparation for the next pandemic. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K. Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2001, 22, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Mizrahi, S. Prologue: The conflict between good governance and open democracy: A crisis of trust. In Managing Democracies in Turbulent Times; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M.E. 11 Democratic theory and trust. Democr. Trust. 1999, 310, 310–345. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, B.J.; Sinha, T. Who is that masked person: The use of face masks on Mexico City public transportation during the Influenza A (H1N1) outbreak. Health Policy 2010, 95, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Q.; Cowling, B.; Lam, W.T.; Ng, M.W.; Fielding, R. Situational awareness and health protective responses to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podlesek, A.; Roškar, S.; Komidar, L. Some factors affecting the decision on non-mandatory vaccination in an influenza pandemic: Comparison of pandemic (H1N1) and seasonal influenza vaccination. Slov. J. Public Health 2011, 50, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Zani, B. A social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk perception and recommended behaviors in Italy. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2011, 31, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D. America Is Having a Moral Convulsion. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/10/collapsing-levels-trust-are-devastating-america/616581 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Quinn, S.C.; Kumar, S.; Freimuth, V.S.; Kidwell, K.; Musa, D. Public willingness to take a vaccine or drug under Emergency Use Authorization during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Biosecur. Bioterror. Biodef. Strat. Pract. Sci. 2009, 7, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, P.R.; Sigelman, L. Trust in government: Personal ties that bind? Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D. Understanding the US failure on coronavirus—an essay by Drew Altman. BMJ 2020, 370, m3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L. Analyzing the Patterns in Trump’s Falsehood about Coronavirus. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/27/us/politics/trump-coronavirus-factcheck.html (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Strauss, D.; Singh, M. U.S. Governors and Coronavirus: Who has Responded Best and Worst? The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/17/us-governors-coronavirus-best-worst-andrew-cuomo (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Tan, H.H.; Tan, C.S. Toward the differentiation of trust in supervisor and trust in organization. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2000, 126, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chanley, V.A.; Rudolph, T.J.; Rahn, W.M. The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanley, V.A. Trust in Government in the Aftermath of 9/11: Determinants and Consequences. Polit. Psychol. 2002, 23, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Lüdtke, O.; Trautwein, U.; Morin, A.J. Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: Synergy of person-and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weerd, W.; Timmermans, D.R.; Beaujean, D.J.; Oudhoff, J.; van Steenbergen, J.E. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, T.C.; Cvetkovich, G. Culture, cosmopolitanism, and risk management. Risk Anal. 1997, 17, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayachi, K.; Cvetkovich, G. Public trust in government concerning tobacco control in Japan. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2010, 30, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G.; Roth, C. Salient value similarity, social trust, and risk/benefit perception. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Zingg, A. The role of public trust during pandemics: Implications for crisis communication. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K. Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.-J. A resources–demands approach to sources of job insecurity: A multilevel meta-analytic investigation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, T.M.; Jiang, L.; Benson, W.L. Job insecurity and anticipated job loss: A primer and exploration of possible interventions. In The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search; Klehe, U., van Hooft, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wroe, A. Political trust and job insecurity in 18 European polities. J. Trust. Res. 2014, 4, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keele, L. The authorities really do matter: Party control and trust in government. J. Politics 2005, 67, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M.; Wille, A. Deciphering the Dutch drop: Ten explanations for decreasing political trust in the Netherlands. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2008, 74, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.J.; Pontusson, J. Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2007, 46, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 7, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organizational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, D.P.; Kuhnert, K.W. A theoretical review and empirical investigation of employee trust in management. Public Adm. Q. 1992, 16, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Guh, W.Y.; Lin, S.P.; Fan, C.J.; Yang, C.F. Effects of organizational justice on organizational citizenship behaviors: Mediating effects of institutional trust and affective commitment. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 112, 818–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, R.C. Increasing affective organizational commitment in public organizations: The key role of interpersonal trust. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 1999, 19, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Gender equity and trust in government: Evidence from South Korea. Sex. Gend. Policy 2019, 2, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, M.R.; Rivera, R.E.; Conway, B.P.; Yonkoski, J.; Lupton, P.M.; Giancola, R. Determinants and consequences of social trust. Sociol. Inq. 2005, 75, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Srivastava, K.B. Organizational trust and organizational citizenship behaviour. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Wheeler, A.R. To invest or not? The role of coworker support and trust in daily reciprocal gain spirals of helping behavior. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1628–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.M. Trust-in-supervisor and helping coworkers: Moderating effect of perceived politics. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Cummings, L.L.; Chervany, N.L. Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allum, N.; Patulny, R.; Read, S.; Sturgis, P. Re-evaluating the links between social trust, institutional trust and civic association. In Spatial and Social Disparities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, P. Association memberships and generalized trust: A multilevel model across 31 countries. Soc. Forces 2007, 86, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, H.; Taguchi, A.; Ryu, S.; Nagata, S.; Murashima, S. Institutional trust in the national social security and municipal healthcare systems for the elderly in Japan. Health Promot. Int. 2012, 27, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Belief in a just world mediates the relationship between institutional trust and life satisfaction among the elderly in China. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 83, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J. Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos 2006, 59, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Kier, C.; Fung, T.; Fung, L.; Sproule, R. Searching for happiness: The importance of social capital. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E.; Vosgerau, J.; Acquisti, A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoli, A.; Probst, T.M.; Lee, H.J. Economic stressors, COVID-19 attitudes, worry, and behaviors among US working adults: A mixture analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Lee, H.J.; Bazzoli, A. Economic stressors and the enactment of CDC-recommended COVID-19 prevention behaviors: The impact of state-level context. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, T.M. Development and validation of the Job Security Index and the Job Security Satisfaction Scale: A classical test theory and IRT approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHorney, C.A.; Ware, J.E., Jr. Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey. Med. Care 1995, 33, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Struct. Equ. Model. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.J.; Morizot, J.; Boudrias, J.S.; Madore, I. A multifoci person-centered perspective on workplace affective commitment: A latent profile/factor mixture analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund-Gibson, K.; Grimm, R.; Quirk, M.; Furlong, M. A latent transition mixture model using the three-step specification. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakk, Z.; Vermunt, J.K. Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2016, 23, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J.R.; Bauer, D.J. Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.; Grimm, K.J. Methods and measures: Growth mixture modeling: A method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.B.; Mamerow, L.; Taylor, A.W.; Henderson, J.; Ward, P.R.; Coveney, J. Demographic indicators of trust in federal, state and local government: Implications for Australian health policy makers. Aust. Health Rev. 2012, 37, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohle, S.; Wingen, T.; Schreiber, M. Acceptance and adoption of protective measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of trust in politics and trust in science. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Balcetis, E.; Bastian, B.; Berkman, E.T.; Bosson, J.K.; Brannon, T.N.; Tomiyama, A.J. Psychological science in the wake of COVID-19: Social, methodological, and meta-scientific considerations. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.L.; Branyiczki, I.; Bigley, G.A. Insufficient bureaucracy: Trust and commitment in particularistic organizations. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, B.; Cristea, M.; Agostini, M.; Belanger, J.J.; Gützkow, B.; Kreienkamp, J.; Reitsema, A.M.; van Breen, J.; Abakoumkin, G.; et al. Trust in government and its associations with health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, K.; Stolle, D.; Zmerli, S. Social and political trust. Oxf. Handb. Soc. Polit. Trust. 2018, 37, 961–976. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Huang, H. How’s your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2008, 38, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mækelæ, M.J.; Reggev, N.; Dutra, N.; Tamayo, R.M.; Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Klevjer, K.; Pfuhl, G. Perceived efficacy of COVID-19 restrictions, reactions and their impact on mental health during the early phase of the outbreak in six countries. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center Trust and Distrust in America. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/07/22/trust-and-distrust-in-america (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Barnett, J.; Cooper, H.; Senior, V. Belief in public efficacy, trust, and attitudes toward modern genetic science. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2007, 27, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. Public trust in government in Japan and South Korea: Does the rise of critical citizens matter? Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Ngo, H.Y. Ethical leadership behavior and employee justice perceptions: The mediating role of trust in organization. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztompka, P. Trust: A Sociological Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, M.; Åström, J.; Adenskog, M. Democratic innovation in times of crisis: Exploring changes in social and political trust. Policy Internet 2021, 13, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, G.; Neale, M.C. Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors: Resolution by maximum likelihood? Multivar. Behav. Res. 2006, 41, 499–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. 2019. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- McLarnon, M.J.; O’Neill, T.A. Extensions of auxiliary variable approaches for the investigation of mediation, moderation, and conditional effects in mixture models. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 955–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, J. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Wileden, L.; Rodems, R. Reach and Impact of Federal Stimulus Checks in Detroit. Available online: https://poverty.umich.edu/files/2020/07/Poverty-Solutions_Brief_DMACS_Stimulus_7142020.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Simmel, G. The Sociology of Georg Simmel; Wolff, K., Ed.; Free Press: Glencoe, MN, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 60.9 |

| Female | 39.1 |

| Race | |

| African American or Black | 11.5 |

| American Indian or Native American | 0.6 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 7.4 |

| Anglo/White | 69.8 |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 9.3 |

| Other | 1.3 |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school diploma | 0.3 |

| High school diploma or GED | 8.7 |

| High school diploma plus some technical training or apprenticeship | 1.0 |

| Some college | 22.8 |

| Graduate from college (BA/BS or other Bachelor’s degree) | 49.8 |

| Some graduate school | 2.4 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 15.0 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living with a partner | 55.7 |

| Separated | 1.4 |

| Divorced | 5.7 |

| Widowed | 0.5 |

| Never married | 36.6 |

| Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 1.9 |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 6.6 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 8.6 |

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 12.8 |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 12.5 |

| $50,000 to $59,999 | 11.6 |

| $60,000 to $69,999 | 11.6 |

| $70,000 to $79,999 | 10.1 |

| $80,000 to $89,999 | 5.0 |

| $90,000 to $99,999 | 4.8 |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 10.2 |

| $150,000 or more | 4.4 |

| Industrial sectors | |

| Accommodation or food services | 4.9 |

| Administration and Support Services | 4.6 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting | 0.8 |

| Arts, entertainment or recreation | 3.1 |

| Construction | 3.5 |

| Educational Services | 8.1 |

| Finance or Insurance | 11.7 |

| Health Care or Social Assistance | 9.1 |

| Information | 8.1 |

| Management of companies or enterprises | 2.8 |

| Manufacturing | 8.2 |

| Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction | 0.1 |

| Other Services | 1.9 |

| Professional, Scientific or Technical Services | 13.7 |

| Real Estate, Rental and Leasing | 1.2 |

| Retail Trade | 11.3 |

| Self-Employed | 0.9 |

| Transportation or Warehousing | 3.5 |

| Utilities | 0.6 |

| Other | 2.1 |

| Variable | Definition | Items & Origin | Response Option | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in federal government (Time 1) | Beliefs about the degree to which the federal government are honest, care for the public, have benevolent and caring intentions towards the public, and make a good faith effort to react to the needs and concerns of the public [2]. | Read each statement and indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each [2]. (1) I trust the leaders of the federal government to make decisions that are good for everyone in the U.S. (2) People’s basic rights are well protected by the federal government (3) The federal government cares about the well-being of everyone in the U.S. (4) The federal government is honest (5) The federal government considers the views of the people in the U.S. (6) The federal government takes account of the needs and concerns of the people in the U.S. (7) The federal government gives honest explanations for their actions to the people in the U.S. | 1–7 strongly disagree to strongly agree | 0.96 |

| Trust in state government (Time 1) | Beliefs about the degree to which the state government are honest, care for the public, have benevolent and caring intentions towards the public, and make a good faith effort to react to the needs and concerns of the public [2]. | Read each statement and indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each [2]. (1) I trust the leaders of the state government to make decisions that are good for everyone in the state (2) People’s basic rights are well protected by the state government (3) The state government cares about the well-being of everyone in the state (4) The state government is honest (5) The state government considers the views of the people in the state (6) The state government takes account of the needs and concerns of the people in the state (7) The state government gives honest explanations for their actions to the people in the state | 1–7 strongly disagree to strongly agree | 0.97 |

| Attitudes toward COVID-19 prevention guidelines (Time 2) | The extent to which individuals have positive attitudes toward the recommended COVID-19 prevention guidelines [59] | Please indicate your thoughts regarding physical/social distancing and hygiene recommendations from the CDC [59]. (1) It is important to maintain a distance of at least 6 ft. from others when out in public or at work. (2) Staying at home except to conduct essential tasks (e.g., grocery shopping, medical appointments) is an effective way of stopping the spread of COVID-19. (3) Disinfecting frequently used items and surfaces is beneficial to prevent spreading the virus. (4) Frequently washing hands for a minimum of 20 s can reduce the spread of the virus. (5) Avoiding touching my face will help protect me from COVID-19. (6) When coughing or sneezing, people should aim inside their elbow or into a tissue. (7) The economic cost of social distancing measures is worth the price to protect public health. (8) Wearing a mask (e.g., N95 respirator masks, medical masks, or fabric masks) while out in public can reduce my chances of potentially spreading COVID-19 to others. | 1–7 strongly disagree to strongly agree | 0.90 |

| Behavioral compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines (Time 2) | The extent to which individuals comply with the recommended COVID-19 prevention guidelines [60] | Please indicate how often you currently engage in the following behaviors to prevent spreading the coronavirus [60]. (1) I maintain a distance of at least 6 ft. from others when out in public or at work; (2) I stay at home except to conduct essential tasks (e.g., grocery shopping, medical appointments). (3) I disinfect frequently used items and surfaces. (4) I frequently wash hands for a minimum of 20 s. (5) I avoid touching my face. (6) When coughing or sneezing, I aim inside my elbow or into a tissue. (7) I wear a mask (e.g., N95 respirator masks, medical masks, or fabric masks) when I am out in public. | 1–5 Never to always | 0.84 |

| Perceived job insecurity (Time 2) | “perceived threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced” ([28], p. 1911) | What is your FUTURE EMPLOYMENT like in your organization? [61] My future employment is: (1) Sure (2) Unpredictable (3) Up in the air (4) Stable (5) Questionable (6) Unknown (7) My job is almost guaranteed (8) Can depend on being here (9) Certain | No Don’t know Yes | 0.97 |

| Affective commitment (Time 2) | Employees’ sense of belonging towards and identification with their employer that increases their involvement in the organization’s activities, their willingness to pursue the organization’s goals, and their desire to stay with the organization [35] | The following statements are about how you feel about your organization. Please read each statement carefully and indicate to what extent you agree that each of the following statements [62]. (1) I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. (2) I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own. (3) I do not feel a strong sense of “belonging” to my organization. (4) I do not feel “emotionally attached” to this organization. (5) I do not feel like “part of the family” at my organization. (6) This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me. | 1–7 strongly disagree to strongly agree | 0.94 |

| Helping behaviors (Time 2) | Voluntarily helping others with, or the prevention of, work-related problems [41] | Read each statement and indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each [63]. (1) I help others who have been absent. (2) I help others who have heavy workloads. (3) I take time to listen to co-workers’ problems and worries. (4) I go out of my way to help new employees. | 1–7 strongly disagree to strongly agree | 0.88 |

| Psychological well-being (Time 2) | The extent to which individuals experience positive emotions [64]. | During the past month… [65] (1) How often have you been a very nervous person? (2) How often have you felt calm and peaceful? (3) How often have you felt downhearted and blue? (4) How often have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? (5) How often were you a happy person? | 1–6 none of the time to all of the time | 0.90 |

| N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust in federal government | 492 | 3.31 | 1.60 | 0.96 | |||||||

| 2. Trust in state government | 492 | 4.26 | 1.51 | 0.45 ** | 0.97 | ||||||

| 3. COVID-19 attitudes | 422 | 6.18 | 1.00 | −0.07 | 0.19 ** | 0.90 | |||||

| 4. COVID-19 behaviors | 410 | 3.99 | 0.69 | −0.01 | 0.20 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.84 | ||||

| 5. Job insecurity | 399 | 0.91 | 1.18 | −0.20 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.97 | |||

| 6. Helping behavior | 386 | 5.50 | 1.13 | 0.19 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.32 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.88 | ||

| 7. Affective commitment | 399 | 4.55 | 1.69 | 0.28 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.07 | 0.25 ** | −0.45 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.94 | |

| 8. Psychological well-being | 422 | 4.44 | 1.20 | 0.18 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.10 * | 0.15 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.90 |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor | 2522.25 | 77 | 0.535 | 0.450 | 0.255 | 0.255 |

| Two-factor | 372.57 | 76 | 0.944 | 0.932 | 0.089 | 0.024 |

| No. of Profiles | LL | FP | SABIC | BLRT (p) | LMR (p) | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −1301.11 | 7 | 2623.35 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2616.21 | 2645.57 | 0.840 |

| 3 | −1258.43 | 10 | 2547.05 | 0.1371 | 0.1260 | 2536.85 | 2578.79 | 0.763 |

| 4 | −1205.60 | 13 | 2450.46 | 0.0129 | 0.0150 | 2437.19 | 2491.72 | 0.833 |

| 5 | −1185.18 | 16 | 2418.68 | 0.0057 | 0.0071 | 2402.35 | 2469.46 | 0.862 |

| 6 | −1165.85 | 19 | 2389.08 | 0.1637 | 0.1741 | 2369.69 | 2449.38 | 0.841 |

| 7 | −1152.87 | 22 | 2372.20 | 0.0785 | 0.0856 | 2349.75 | 2442.02 | 0.831 |

| Profile | N | % of Sample | Trust in Federal Government | Trust in State Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Trustor | 130 | 26.5% | 5.486 | 5.774 |

| State Trustor | 126 | 25.7% | 1.777 | 5.278 |

| The ambivalent | 117 | 23.9% | 3.741 | 4.170 |

| Distrustor | 106 | 21.6% | 1.742 | 1.948 |

| Federal Trustor | 11 | 2.3% | 4.912 | 1.928 |

| Federal Trust (a) | Distrust (b) | High Trust (c) | State Trust (d) | Ambivalent (e) | Chi Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Attitudes | 5.892 d | 6.068 d | 6.252 d,e | 6.596 a,b,c,e | 5.849 c,d | 42.02 *** |

| COVID-19 Compliance | 3.750 c,d | 3.914 d | 4.105 a,e | 4.227 a,b,e | 3.743 c,e | 21.93 *** |

| Perceived job insecurity | 0.877 | 1.187 c | 0.482 b,d,e | 1.012 c | 1.017 c | 26.71 ** |

| Affective commitment | 3.714 c | 3.804 c,d,e | 5.369 a,b,d,e | 4.572 b,c | 4.408 b,c | 55.438 *** |

| Helping behavior | 4.819 | 5.105 c,d | 5.916 b,d,e | 5.607 b,c | 5.330 c | 36.24 *** |

| Psychological well-being | 5.015 b | 4.061 a,c | 4.781 b,d,e | 4.374 c | 4.444 c | 19.40 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Bettac, E.L.; Lee, H.J.; Probst, T.M. In Whom Do We Trust? A Multifoci Person-Centered Perspective on Institutional Trust during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031815

Jiang L, Bettac EL, Lee HJ, Probst TM. In Whom Do We Trust? A Multifoci Person-Centered Perspective on Institutional Trust during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031815

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Lixin, Erica L. Bettac, Hyun Jung Lee, and Tahira M. Probst. 2022. "In Whom Do We Trust? A Multifoci Person-Centered Perspective on Institutional Trust during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031815

APA StyleJiang, L., Bettac, E. L., Lee, H. J., & Probst, T. M. (2022). In Whom Do We Trust? A Multifoci Person-Centered Perspective on Institutional Trust during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031815