“We Are Young, We Run Free”: Predicting Factors of Life Satisfaction among Young Backpackers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

1.2. Risk-Taking Behaviors

1.3. Personal Resources

1.4. Environmental Resources

1.5. The Study Goals

2. Materials and Methods

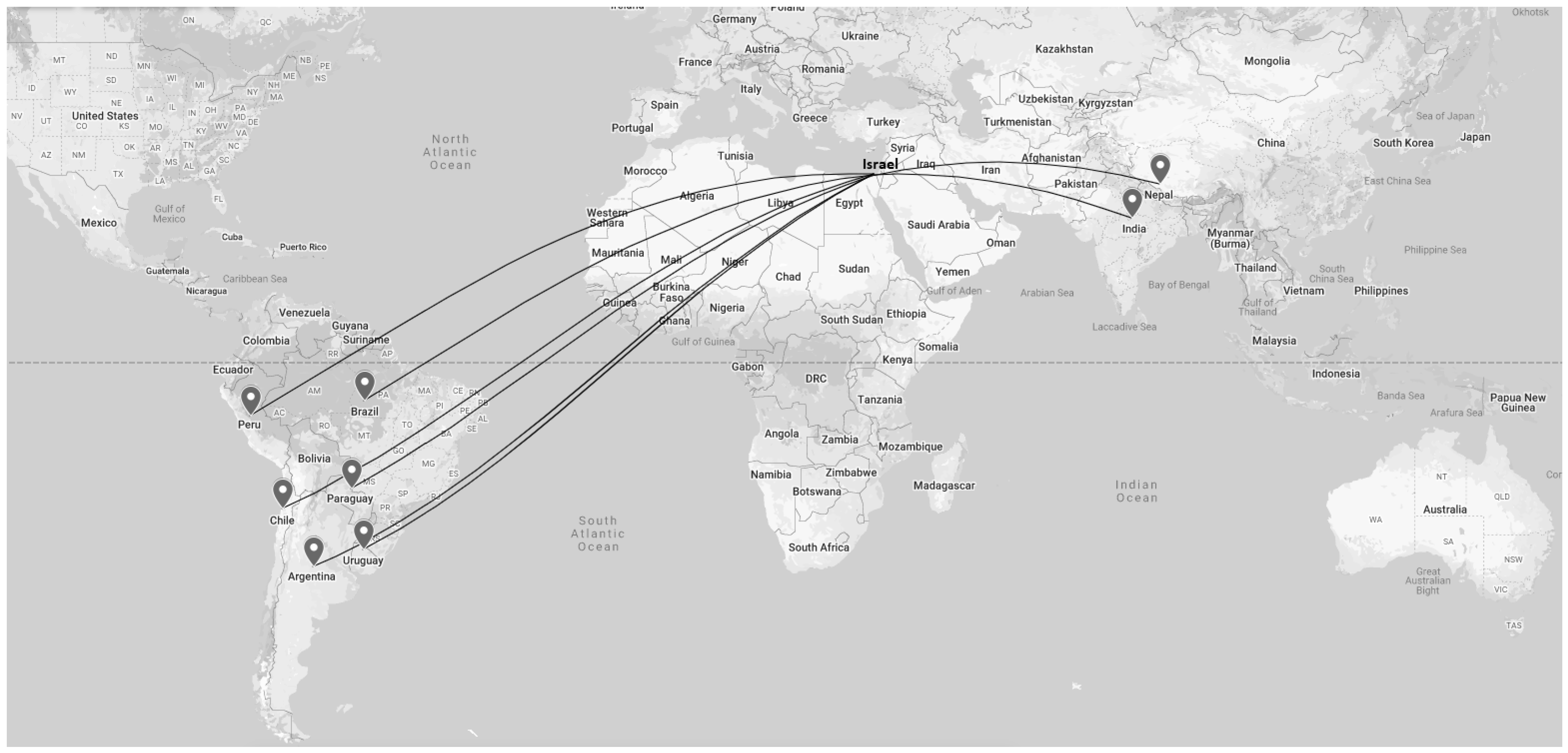

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Multivariate Prediction of Life Satisfaction

3.2. Mediation Analyses of the Association between Risk-Taking Behaviors, Personal Resources, and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Variable | Source | Number of Items | Answers Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | 0 = male; 1 = female | |

| Religiosity | 1 | 0 = secular; 1 = religious | |

| Year of birth | 1 | - | |

| Country of birth | 1 | 0 = Israel; 1 = other | |

| Father’s country of birth | 1 | 0 = Israel; 1 = other | |

| Level of education | 1 | 0 = does not have high school diploma 1 = has high school diploma | |

| Duration of the trip abroad | 1 | - | |

| Place of residence at the time of the research | 1 | 1-India; 2-Nepal; 3-South America | |

| Life satisfaction | Huebner (1991) [78] | 7 | 1 (never) to 4 (almost always) |

| Risk-taking behaviors | Shapiro, Siegel, Scovill, and Hays 1998; Siegel et al. 1994 [79] | 13 | 1 (never) to 4 (almost always) |

| Sense of mastery | Pearlin and Schooler (1978) [42] | 7 | 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) |

| Self-esteem | Rosenberg (1965) [81] | 10 | 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) |

| Social support | Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley (1988) [82] | 12 | 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree) |

| Community participation | Itzhaky and York (1994) [83] | 4 | 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (strongly agree) |

References

- Reichel, A.; Fuchs, G.; Uriely, N. Perceived risk and the non-institutionalized tourist role: The case of Israeli student ex-backpackers. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Richards, G. Suspending reality: An exploration of enclaves and the backpacker experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N.; Yonay, Y.; Simchai, D. Backpacking experiences: A type and form analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bao, J.; Huang, S. Segmenting Chinese backpackers by travel motivations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayour, F.; Kimbu, A.N.; Park, S. Backpackers: The need for reconceptualisation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. The Backpacker Phenomenon; James Cook University: Townsville, Australia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, S.; Wearing, S.; Lyons, K.; Tarrant, M.; Landon, A. A rite of passage? Exploring youth transformation and global citizenry in the study abroad experience. Tour. Recreat. 2017, 42, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Žukauskienė, R.; Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J.E.; Archer, S.L. Identity status in late adolescents: Scoring criteria. In Ego Identity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 205–240. [Google Scholar]

- Benolol, N. The relationship between backpacking and adaptation to the workforce during emerging adulthood. World Leis. 2017, 59, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, S.; Blatt, S.J.; Walsh, S. The extended journey and transition to adulthood: The case of Israeli backpackers. J. Youth Stud. 2006, 9, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X. Career decision self-efficacy and life satisfaction in China: An empirical analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Mousanezhad Jeddi, E. Relationship between wisdom, perceived control of internal states, perceived stress, social intelligence, information processing styles and life satisfaction among college students. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Life Satisfaction. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. National accounts of subjective well-being. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, F.M.; Robinson, J.P. Measures of subjective wellbeing. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1991; Volume 1, pp. 61–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, T.; Huebner, E.S. Adolescents’ perceived quality of life: An exploratory investigation. J. Sch. Psychol. 1994, 33, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.G.; Diener, E. Who is happy? Psychol. Sci. 1995, 6, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Lilly, R.S. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, B.W.; Bengtson, V.L.; Peterson, J.A. An exploration of the activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. J. Gerontol. 1972, 27, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R. Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: Relative standards, need fulfillment, culture, and evaluation theory. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Látková, P.; Sun, Y.Y. The relationship between leisure and life satisfaction: Application of activity and need theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 86, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.P.; Miller, D.C.; Schafer, W.D. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaehler, N.; Piyaphanee, W.; Kittitrakul, C.; Kyi, Y.P.; Adhikari, B.; Sibunruang, S.; Jearraksuwan, S.; Tangpukdee, N.; Silachamroon, U.; Tantawichien, T. Sexual behavior of foreign backpackers in the Khao San road area, Bangkok. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2013, 44, 690–696. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G. Low versus high sensation-seeking tourists: A study of backpackers’ experience risk perception. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbeck, M.; Agardh, A.; Östergren, P.-O. Travel abroad increases sexual health risk-taking among Swedish youth: A population-based study using a case-crossover strategy. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1330511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayne, M.; Gibson, C.; Waitt, G.; Valentine, G. Drunken mobilities: Backpackers, alcohol, ‘doing place’. Tour. Stud. 2012, 12, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.T.; De Wildt, G. Sexual behaviour of backpackers who visit Koh Tao and Koh Phangan, Thailand: A cross-sectional study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016, 92, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, P.; Sundbeck, M.; Persson, K.I.; Stafström, M.; Östergren, P.-O.; Mannheimer, L.; Agardh, A. A meta-analysis and systematic literature review of factors associated with sexual risk-taking during international travel. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Hardy, S.A.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Meca, A.; Waterman, A.S.; Picariello, S.; Luyckx, K.; Coretti, E.; Yeong Kim, S.; Brittian, A.S.; et al. Identity in young adulthood: Links with mental health and risky behavior. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 36, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: Developmental Period Facilitative of the Addictions. Eval. Health Prof. 2014, 37, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Choi, E. Life satisfaction and delinquent behaviors among Korean adolescents. Pers. Individ. 2017, 104, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, D.; Xian, H.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G. Examining the relationships between life satisfaction and alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use among school-aged children. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Music, M.; Abidovic, A.; Babic, N.; Mujaric, E.; Dervisevic, S.; Slatina, E.; Salibasic, M.; Tuna, E. Life satisfaction and risk-taking behavior in secondary schools adolescents. Mater. Socio-Med. 2013, 25, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tartaglia, S.; Miglietta, A.; Gattino, S. Life satisfaction and cannabis use: A study on young adults. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæther, S.M.M.; Knapstad, M.; Askeland, K.G.; Skogen, J.C. Alcohol consumption, life satisfaction and mental health among Norwegian college and university students. Addict. Behav. 2019, 10, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baláž, V.; Valuš, L. Migration, risk tolerance and life satisfaction: Evidence from a large-scale survey. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1603–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, I.F.; Patil, G.G.; Nes, R.B.; Clench-Aas, J. The relationship between physical functional limitations, and psychological distress: Considering a possible mediating role of pain, social support and sense of mastery. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 4, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Wallfish, S. Coping with a threat to life: A longitudinal study of self-concept, social support, and psychological distress. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1984, 12, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schooler, C. The structure of coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levy, D.; Benbenishty, R.; Refaeli, T. Life satisfaction and positive perceptions of the future among youth at-risk participating in Civic-National Service in Israel. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 10, 2012–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Simón Márquez, M.D.M.; Saracostti, M. Parenting practices, life satisfaction, and the role of self-esteem in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. 2019, 16, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proctor, C.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Very happy youths: Benefits of very high life satisfaction among adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 98, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, J. Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction amongst Afghan and Indian University Students. Int. J. Creat. Res. 2020, 8, 2320–2882. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Knight, B.G. Caregiving subgroups differences in the associations between the resilience resources and life satisfaction. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 37, 1540–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, B.D.; Brown, E.; Caldwell, C.H. Personal mastery and psychological well-being among young grandmothers. J. Women Aging 2012, 24, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilman, R.; Huebner, E.S. Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblom, R.; Houlihan, D.; Nolan, J.D. An assessment of resiliency and life satisfaction in high school-aged students in Belize. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, W.; Vincent, C.; Yi, K.C.W.; Wang, H.H.H. Age of possibilities: Emerging adults and life satisfaction. In Proceedings of the AAICP 2018, Asian Association of Indigenous and Cultural Psychology (AAICP) International Conference Proceedings, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 25–27 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Brownell, A. Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, D. Backpackers’ motivations the role of culture and nationality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.M.; Musa, G.; Thirumoorthi, T. A comparison between Asian and Australasia backpackers using cultural consensus analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenberger, I. Why the host community just isn’t enough: Processes and impacts of backpacker social interactions. Tour. Stud. 2017, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M. Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinisman, T. Life satisfaction in the transition from care to adulthood: The contribution of readiness to leave care and social support. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2014, 21, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaeli, T.; Benbenishty, R.; Zeira, A. Predictors of life satisfaction among care leavers: A mixed-method longitudinal study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 99, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on Facebook: An examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, V.; Meggiolaro, S.; Rivellini, G.; Zaccarin, S. Social relations and life satisfaction: The role of friends. Genus 2018, 74, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xia, M.; Han, M.; Liang, Y. Social support and resilience as mediators between stress and life satisfaction among people with substance use disorder in China. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, S.J.; Goodwin, A.D. Optimism and well-being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. Int. J. Aging Hum. 2010, 71, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Yang, G.; Skora, E.; Wang, G.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, W. Self-esteem, social support, and life satisfaction in Chinese parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 2015, 17, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, B.; Boyd, N. Viewing community as responsibility as well as resource: Deconstructing the theoretical roots of psychological sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadan, E. Avoda kehilatit: Shitot Leshinui Hevrati Community Work: Methods for Social Change; Hakibbutz Hameuhad Publishers: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaky, H.; Bustin, E. Promoting client participation by social workers. J. Community Pract. 2005, 13, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Pratt, M.W.; Pancer, S.M.; Olsen, J.A.; Lawford, H.L. Community and religious involvement as contexts of identity change across late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, C.; Levine, P. Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. Future Child 2010, 20, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.K. Emerging Adulthood in Hong Kong: Social Forces and Civic Engagement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.L.; Probert, S. Civic engagement in relation to outcome expectations among African American young adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 32, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.J.; Lewin, T.J.; Stain, H.J.; Coleman, C.; Fitzgerald, M.; Perkins, D.; Carr, V.J.; Fargar, L.; Fuller, J.; Lyne, D.; et al. Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 46, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.K.; Suarez, M.C.; Leon, M.; Trinidad, N. Sense of community, participation, and life satisfaction among Hispanic immigrants in rural Nebraska. Kontakt 2017, 19, e284–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Lai, D.W.; Yip, H.M.; Chan, S.; Lai, S.; Chaudhury, H.; Scharlach, A.; Leeson, G. Sense of community mediating between age-friendly characteristics and life satisfaction of community-dwelling older adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.C.; Nyutu, P.; Tran, K.; Spears, A. Finding resilience: The mediation effect of sense of community on the psychological well-being of military spouses. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2015, 37, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yetim, U. The impacts of individualism/collectivism, self-esteem, and feeling of mastery on life satisfaction among the Turkish University students and academicians. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.S.; Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1991, 12, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.; Siegel, A.W.; Scovill, L.C.; Hays, J. Risk-taking patterns of female adolescents: What they do and why. J. Adolesc. 1988, 21, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, A.W.; Cousins, J.H.; Rubovits, D.S.; Parsons, J.T.; Lavery, B.; Crowley, C.L. Adolescents’ perceptions of the benefits and risks of their own risk taking. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 1994, 2, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itzhaky, H.; York, A.S. Different types of client participation and the effects on community-social work intervention. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1994, 19, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Model Templates for PROCESS for SPSS and SAS. Available online: https://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/process_templates.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Garry, J.; Lohan, M. Mispredicting happiness across the adult lifespan: Implications for the risky health behaviour of young people. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazos, K. Backpacking through an ontology of becoming: A never-ending cycle of journeys. Int. J. 2016, 18, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, L.; Paz, A.; Potasman, I. Drug abuse in travelers to southeast Asia: An on-site study. J. Travel Med. 2005, 12, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Refaeli, T.; Itzhaky, H. Which road will I take? Predictors of risk-taking behaviour among young backpackers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, K.B.; Curlette, W.L.; Aysan, F.; Herrington, A.; Gfroerer, C.A.; Thompson, D.; Hamarat, E. Coping resources, perceived stress, and life satisfaction among Turkish and American University students. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2002, 9, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M.; Jovanović, V. The relationship between gender and life satisfaction: Analysis across demographic groups and global regions. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, T.; McDonald, A.; Von Mach, T.; Witherspoon, D.P.; Lambert, S. Patterns of social connectedness and psychosocial wellbeing among African American and Caribbean Black adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 2271–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymańska, P. The role of siblings in the process of forming life satisfaction among young adults–moderating function of gender. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 6132–6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Developmental dynamics between young adults’ life satisfaction and engagement with studies and work. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 2017, 8, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zullig, K.J.; Ward, R.M.; Horn, T. The association between perceived spirituality, religiosity, and life satisfaction: The mediating role of self-rated health. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 79, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, A.; Ruch, W. Satisfaction with life and character strengths of non-religious and religious people: It’s practicing one’s religion that makes the difference. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villani, D.; Sorgente, A.; Iannello, P.; Antonietti, A. The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, C.; Putnam, R.D. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 914–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salmani, S.; Biderafsh, A.; Aliakbarzadeh Arani, Z. The relationship between spiritual development and life satisfaction among students of qom university of medical sciences. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1889–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, Y.M.C.; Lee, M. Mapping the life satisfaction of adolescents in hong kong secondary schools with high ethnic concentration. Youth Soc. 2013, 48, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, D.; Bekerman, Z. Chabad tracks the trekkers: Jewish education in India. J. Jew. Educ. 2009, 75, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | %/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 318 | 23.76 (1.56) |

| Gender (female = 1) | 176 | 55.3% |

| Country of birth (Israel = 1) | 297 | 93.4% |

| Father’s country of birth (Israel = 1) | 248 | 81.3% |

| Religiosity (religious = 1) | 91 | 28.6% |

| Education (high school diplomas = 1) | 284 | 89.6% |

| Place of stay abroad | ||

| South America | 185 | 58.4% |

| India | 73 | 23.0% |

| Nepal | 55 | 17.3% |

| Average stay abroad | 314 | 3.48 (2.90) |

| R2 | ΔR2 | B | SE | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.04 ** | ||||

| Gender a | −0.18 | 0.06 | −0.13 * | ||

| Religiosity b | −0.21 | 0.09 | −0.14 * | ||

| Step 2 | 0.21 *** | 0.17 *** | |||

| Risk-taking behaviors | −0.51 | 0.06 | −0.42 *** | ||

| Step 3 | 0.66 *** | 0.45 *** | |||

| Sense of mastery | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.41 *** | ||

| Self-esteem | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.42 *** | ||

| Step 4 | 0.69 *** | 0.04 *** | |||

| Social support | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.20 *** | ||

| Community participation | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.15 *** |

| Independent Variable | Mediator | Direct Effect (c Path) | Indirect Effect (c′ Path) | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-taking behaviors | Social support | −0.42 *** | −0.13 ** | −0.376, −0.205 |

| Community participation | −0.36 *** | −0.127, 0.002 | ||

| Sense of mastery | Social support | 0.77 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.108, 0.253 |

| Community participation | 0.67 *** | 0.057, 0.139 | ||

| Self-esteem | Social support | 0.76 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.129, 0.255 |

| Community participation | 0.67 *** | 0.058, 0.141 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Refaeli, T.; Weiss-Dagan, S.; Levy, D.; Itzhaky, H. “We Are Young, We Run Free”: Predicting Factors of Life Satisfaction among Young Backpackers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031429

Refaeli T, Weiss-Dagan S, Levy D, Itzhaky H. “We Are Young, We Run Free”: Predicting Factors of Life Satisfaction among Young Backpackers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031429

Chicago/Turabian StyleRefaeli, Tehila, Shlomit Weiss-Dagan, Drorit Levy, and Haya Itzhaky. 2022. "“We Are Young, We Run Free”: Predicting Factors of Life Satisfaction among Young Backpackers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031429

APA StyleRefaeli, T., Weiss-Dagan, S., Levy, D., & Itzhaky, H. (2022). “We Are Young, We Run Free”: Predicting Factors of Life Satisfaction among Young Backpackers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031429