Nighttime Walking with Music: Does Music Mediate the Influence of Personal Distress on Perceived Safety?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

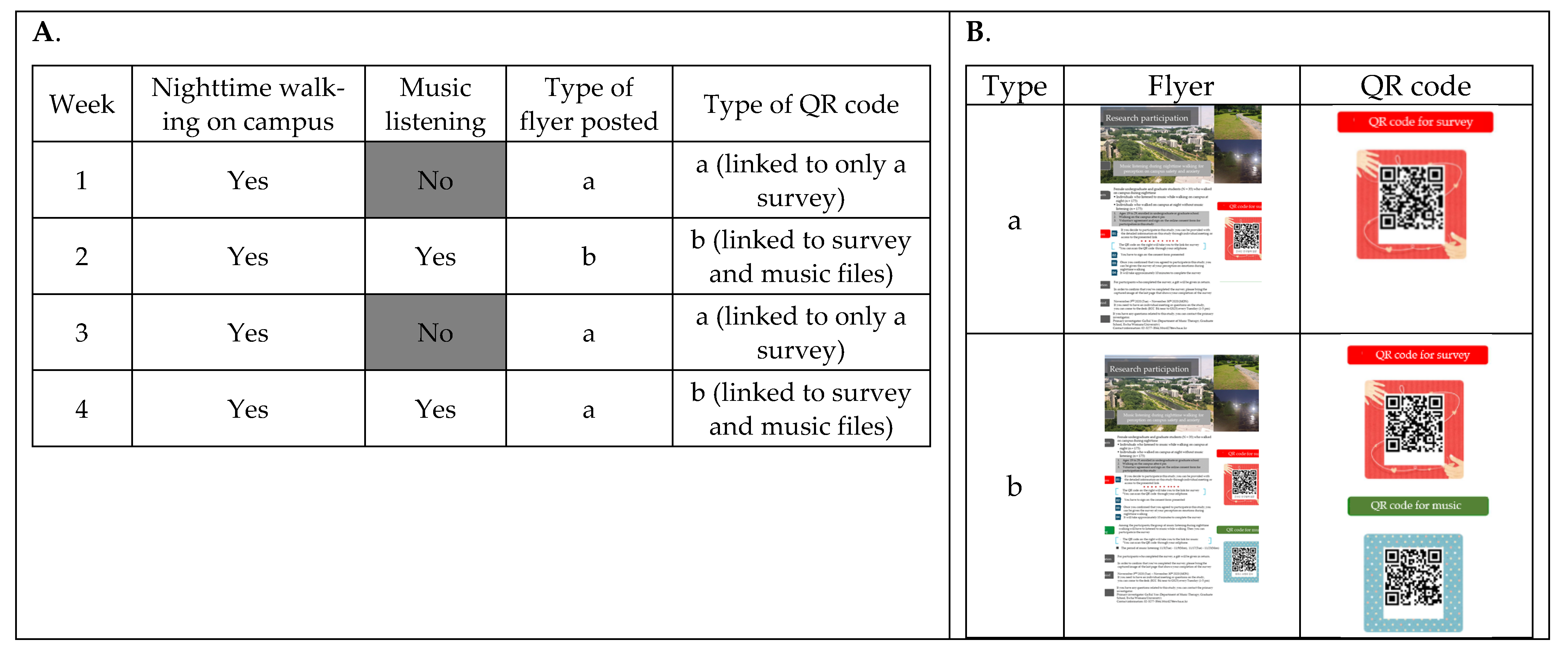

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Music

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Survey

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Safety of Nighttime Walking

3.2. Perception of the Music Listened to during Nighttime Walking

3.3. Factors Related to the Perceived Safety of Nighttime Walking on Campus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Nine items on the perception of nighttime walking |

| 1. The pedestrian pathway was bright. |

| 2. I saw many people walking around me. |

| 3. I was able to see the path clearly. |

| 4. I saw many strangers walking around me. |

| 5. The environment was well-organized. |

| 6. The pathway was clean. |

| 7. The pathway was familiar. |

| 8. I was satisfied with my experience of walking the pathway. |

| 9. I felt that walking the pathway was safe. |

| Eight items on the perception of music listening during nighttime walking |

| 1. I was aware of the music being played. |

| 2. I was attentive to the music. |

| 3. I was satisfied with the type of music played. |

| 4. I was satisfied with the loudness of the music. |

| 5. Music made me feel safer while walking. |

| 6. Music made nighttime walking more satisfying. |

| 7. Music made nighttime walking uncomfortable. |

| 8. Music interfered with walking at nighttime. |

References

- MacDonald, R.A.R. Music, health, and well-being: A review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2013, 8, 20635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meng, Q.; Zhao, T.; Kang, J. Influence of music on the behaviors of crowd in urban open public spaces. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kipnis, G.; Tabak, N.; Koton, S. Background music playback in the preoperative setting: Does it reduce the level of preoperative anxiety among candidates for elective surgery? J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2016, 31, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.J.A.; Polascik, B.A.; Kee, H.M.; Hui Lee, A.C.; Sultana, R.; Kwan, M.; Raghunathan, K.; Belden, C.M.; Sng, B.L. The effect of perioperative music listening on patient satisfaction, anxiety, and depression: A quasiexperimental study. Anesthesiol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 3761398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talianni, K.; Charitos, D. Soundwalk: An embodied auditory experience in the urban environment. In Workshop Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Intelligent Environments; Botía, J.A., Charitos, D., Eds.; Botía, J.A., Charitos, D., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 684–692. [Google Scholar]

- Leyndo, T.O. Exploring the effect of sound and music on health in hospital settings: A narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Cui, L.; Liu, X.; Han, C.; Qu, S.; Wang, L.; Ji, D. Use of music to enhance sleep and psychological outcomes in critically ill patients: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e037561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; de la Torre-Luque, A.; Diaz-Piedra, C.; Vico, F.J.; Buela-Casal, G.; Dowling, D.; Thibeau, S. Listening to relaxing music improves physiological responses in premature infants. Adv. Neonatal Care 2018, 18, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavia, L.; Witchel, H.J.; Kang, J.; Aletta, F. A preliminary soundscape management model for added sound in public spaces to discourage anti-social and support pro-social effects on public behavior. In Proceedings of the DAGA Conference, Aachen, Germany, 14–17 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cozens, P.; Love, T. A review and current status of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblom, P. Deconstructing CPTED and reconstructing it for practice, knowledge management and research. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2011, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, E.; Krishna, A.; Ardelet, C.; Decré, G.B.; Goudey, A. Sound and safe: The effect of ambient sound on the perceived safety of public spaces. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirsch, L.E. Music in American Crime Prevention and Punishment; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cozens, P.; Sun, M.Y. Exploring crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) and students’ fear of crime at an Australian university campus using prospect and refuge theory. Prop. Manag. 2019, 37, 2287–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Guerette, R.T. Resident students’ perception of safety in on-campus residential facilities: Does crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) make a difference? J. Sch. Violence 2019, 18, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.G.; Gover, A.R.; Pudrzynska, D. Are institutions of higher learning safe? A descriptive study of campus safety issues and self-reported campus victimization among male and female college students. J. Crim. Justice Educ. 2007, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etopio, A.; Crowder, M.K. Perceived campus safety as a mediator of the link between gender and mental health in a national U.S. college sample. Women Health 2019, 59, 703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. A cross-cultural investigation on the effects of physical environment at university dormitory on social interaction among students. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Effects of crime prevention through environmental design on the formation of sense of community through social interaction among students in university campus. J. Community Saf. Secur. Environ. Des. 2018, 9, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.H. A Study on Fears of Crime by Female About Environmental Characteristics of Outdoor Space at Night Within University Campus. Master’s Thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.C.; Ha, M.K. A study on development of crime-free environment in university campus. J. Community Saf. Secur. Environ. Des. 2011, 2, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.J.; Zegeer, C.V.; Huang, H.H.; Cynecki, M.J. A Review of Pedestrian Safety Research in the United States and Abroad; FHWA-RD-03-042; U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, P.; Danuser, B. Affective and physiological responses to environmental noises and music. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2004, 53, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerola, T. Are the emotions expressed in music genre-specific? An audio-based evaluation of datasets spanning classical, film, pop and mixed genres. J. New Music Res. 2011, 40, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Niess, H.; Jauch, K.W.; Bruns, C.J.; Hartl, W.; Welker, L. Overture for growth hormone: Requiem for interleukin-6? Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2709–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knight, W.E.; Rickard, N.S. Relaxing music prevents stress-induced increases in subjective anxiety, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in healthy males and females. J. Music Ther. 2001, 38, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, N.; Padilla, L.A.; Contreras, D.G.; Montelongo, R. Physiological responses in heart rate with classical music. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computing Science and Automatic Control (CCE), Mexico City, Mexico, 5–7 September 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bigand, E.; Vieillard, S.; Madurell, F.; Marozeau, J.; Dacquet, A. Multidimensional scaling of emotional responses to music: The effect of musical expertise and of the duration of the excerpts. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 1113–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.J.; Jeong, E.; Kim, S.J. Listeners’ perception of intended emotions in music. Int. J. Contents 2013, 9, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eerola, T.; Vuoskoski, J.K. A comparison of the discrete and dimensional models of emotion in music. Psychol. Music 2011, 39, 18–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, J.; Chong, H.J.; Kim, A.J. A comparison of emotion identification and its intensity between adults with schizophrenia and healthy adults: Using film music excerpts with emotional content. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2018, 27, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Kang, S.J.; An, E.H.; Lee, K.H.A. Study on the formation of crime prevention environment of the outdoor space in the apartment complex: Regarding neighborhood relationship, outdoor space activation and fear of crime. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2015, 21, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J.; Ayers, S.L.; Marsiglia, F.F. Perceived neighborhood safety and psychological distress: Exploring protective factors. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2012, 39, 138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mwakalonge, J.; Siuhi, S.; White, J. Distracted walking: Examining the extent to pedestrian safety problems. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2015, 2, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Composer | Title of Music | Genre | Instrument | Reference | Tempo (bpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. Elgar | Salut d’Amour | C | Guitar | [23] | 72 |

| E. Grieg | Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 “Morning” | C | Flute/Harp | [24] | 60 |

| W. A. Mozart | Piano Sonata K.570 2nd movement | C | Piano | [25] | 80 |

| J. Pachelbel | Canon | C | Guitar | [26] | 52 |

| S. Rachmaninoff | Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43. Var. 18. | C | Pianos | [27] | 79 |

| R. Schumann | Traumerei, Op. 15, No. 7 | C | Piano | [28] | 84 |

| J. Barry | If I Know a Song of Africa from “Out of Africa” | F | Flute/Strings | [29] | 81 |

| D. Marianelli | The Secret Life of Daydreams from “Pride & Prejudice” | F | Piano/Strings | [30] | 70 |

| D. Marianelli | Dawn from “Pride & Prejudice” | F | Piano | [30] | 66 |

| A. Johnston | Rose Garden from “Becoming Jane” | F | Piano/Strings | [31] | 74 |

| Variable | N = 178 |

|---|---|

| Sex, F:M | 178:0 |

| Age (years), M (SD) | 23.0 (3.5) |

| Year in school | |

| 1st year | 24 (13.4%) |

| 2nd year | 35 (19.6%) |

| 3rd year | 26 (14.5%) |

| 4th year | 50 (27.9%) |

| Graduate | 44 (24.6%) |

| Duration of university attendance (months), M (SD) | 32.9 (22.6) |

| Time period of walking on campus at night | |

| 6–8 p.m. | 130 (72.6%) |

| 8–10 p.m. | 0 (0.0%) |

| 10 p.m.–12 a.m. | 41 (22.9%) |

| 12–2 a.m. | 6 (3.4%) |

| 2–6 a.m. | 2 (1.1%) |

| Purpose of walk | |

| Returning home | 124 (69.3%) |

| Exercising | 15 (8.4%) |

| Walking to a night class | 11 (6.1%) |

| Walking to a campus facility for meeting or event | 15 (8.4%) |

| Walking to the library | 13 (7.3%) |

| Walking to get food | 1 (0.5%) |

| Number of companions | |

| 0 (Walking alone) | 113 (63.1%) |

| 1 | 34 (19.0%) |

| 2 | 15 (8.4%) |

| 3 | 8 (4.5%) |

| 4 | 4 (2.2%) |

| 5 | 5 (2.8%) |

| Item | N = 178 |

|---|---|

| Perceived safety of their last nighttime walk | 3.6 (0.7) |

| Satisfaction with their last nighttime walk | 3.6 (0.9) |

| Level of anxiety felt within the past week | 36.2 (26.0) |

| Level of psychological distress felt within the past week | 36.0 (26.2) |

| Item | Component | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| The pedestrian pathway was clean. | 0.846 | 0.065 |

| The environment was well-organized. | 0.835 | 0.043 |

| I was able to see the path clearly. | 0.715 | 0.005 |

| The pathway was familiar. | 0.558 | −0.546 |

| The pathway was bright. | −0.060 | −0.765 |

| I saw many people walking around me. | 0.328 | −0.682 |

| I saw many strangers walking around me. * | 0.346 | 0.636 |

| Item | N = 178 |

|---|---|

| Items loaded on perception of image control/management | |

| The pedestrian pathway was clean. | 4.0 (0.7) |

| The environment was well-organized. | 3.8 (0.8) |

| I was able to see the path clearly. | 3.4 (0.8) |

| The pathway was familiar. | 4.0 (0.7) |

| Average of the four items | 3.8 (0.6) |

| Items loaded on perception of territoriality | |

| The pathway was bright. | 3.2 (0.8) |

| I saw many strangers walking around me. * | 3.1 (0.5) |

| I saw many people walking around me. | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Average of the three items | 3.1 (0.5) |

| Category | Item | n = 78 |

|---|---|---|

| Attentiveness to music | I was aware of the music being played. | 3.72(0.78) |

| I was attentive to the music. | 3.50(0.91) | |

| Satisfaction with the music provided | I was satisfied with the type of music played. | 3.86(0.82) |

| I was satisfied with the loudness of the music. | 3.91(0.72) | |

| Benefits of the music for feeling safe during nighttime walking | Music made me feel safer while walking. | 3.35(0.97) |

| Music made nighttime walking more satisfying. | 3.76(0.78) | |

| Interference of the music during nighttime walking | Music made nighttime walking uncomfortable. | 2.32(1.09) |

| Music interfered with walking at nighttime. | 2.21(1.06) |

| Variable | Non-Music Listening (n = 100) | Music Listening (n = 78) | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety level | 35.2(25.9) | 36.7(25.9) | −0.391 | 0.696 |

| Psychological distress | 37.4(28.3) | 34.0(23.5) | 0.848 | 0.398 |

| Perception of image control/management a | 0.1 (1.0) | −0.1 (0.9) | 1.756 | 0.081 |

| Perception of territoriality a | −0.1 (0.9) | 0.1 (1.1) | −1.264 | 0.208 |

| Variable | Age | # of Months Attending University | Number of Companions | Anxiety | Psychological Distress | Perception of Image Control/Management a | Perception of Territoriality a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived safety of nighttime walking | −0.050 | 0.076 | 0.149 | −0.268 ** | −0.196 | 0.621 ** | 0.481 ** |

| Satisfaction with nighttime walking | −0.284 ** | 0.092 | 0.183 | −0.501 ** | −0.369 * | 0.594 ** | 0.386 ** |

| Variable | Age | # of Months Attending University | Number of Companions | Anxiety | Psychological Distress | Perception of Image Control/Management a | Perception of Territoriality a | Benefits of Music | Interference of Music |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived safety of nighttime walking | −0.171 | 0.067 | 0.064 | 0.041 | 0.098 | 0.584 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.051 |

| Satisfaction with nighttime walking | −0.196 | 0.082 | 0.019 | −0.005 | 0.142 | 0.597 ** | 0.357 * | 0.472 ** | 0.008 |

| Variable | Attentiveness to Music | Satisfaction with Music |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived benefits of music for feeling safe during nighttime walking | 0.521 ** | 0.525 ** |

| Interference of music during nighttime walking | 0.069 | −0.064 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoo, G.E.; Hong, S.J.; Chong, H.J. Nighttime Walking with Music: Does Music Mediate the Influence of Personal Distress on Perceived Safety? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031383

Yoo GE, Hong SJ, Chong HJ. Nighttime Walking with Music: Does Music Mediate the Influence of Personal Distress on Perceived Safety? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031383

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Ga Eul, Sung Jin Hong, and Hyun Ju Chong. 2022. "Nighttime Walking with Music: Does Music Mediate the Influence of Personal Distress on Perceived Safety?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031383

APA StyleYoo, G. E., Hong, S. J., & Chong, H. J. (2022). Nighttime Walking with Music: Does Music Mediate the Influence of Personal Distress on Perceived Safety? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031383