The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Family Business (FB)

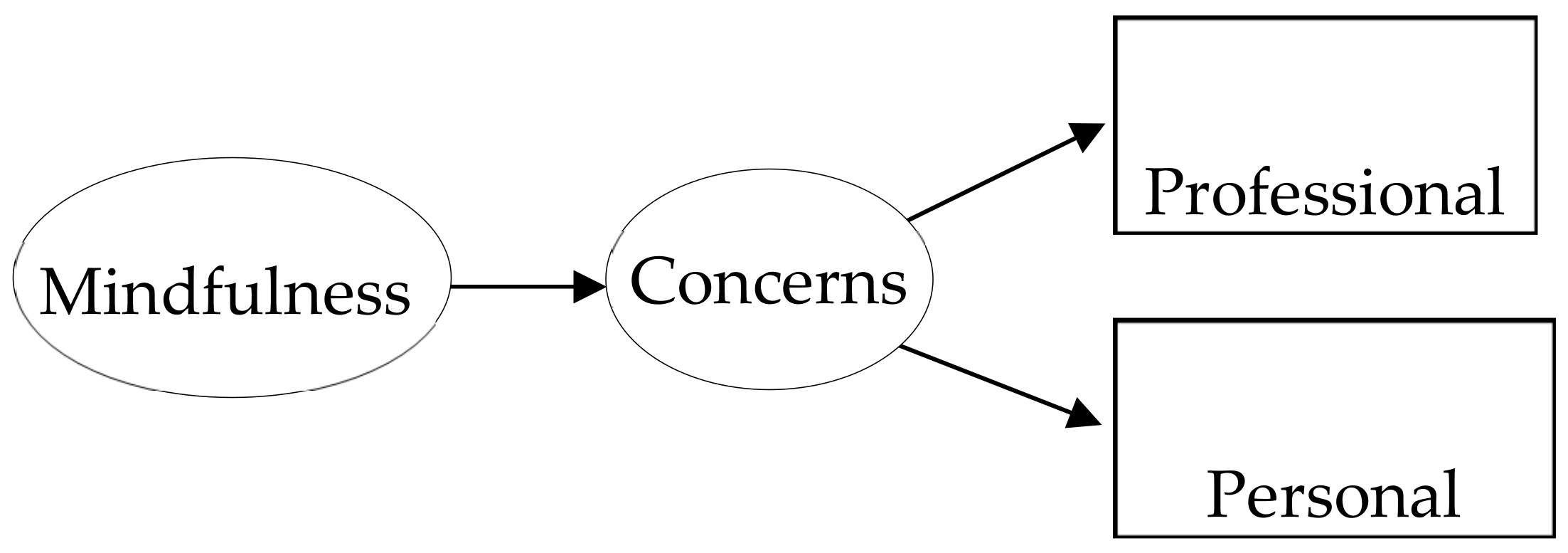

1.2. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) and Concerns about the Future

1.3. The Role of Mindfulness in Emotions and Concerns in University Field

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Context

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weng, Q.D.; McElroy, J. Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Christofor, J.; Kuckertz, A. Explaining Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation: Conceptualization of a Cross-Cultural Research Framework. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2007, 4, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.C.; Weng, Q. The Connections Between Careers and Organizations in the New Career Era: Questions Answered, Questions Raised. J. Career Dev. 2016, 43, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziemianski, P. Identifying and Mitigating the Negative Effects of Power in Organizations. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2021, 19367244211014789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for Its Salutary Effects. Psych. Inquiry 2007, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, E.; Brummel, B.J. Examining Workplace Mindfulness and Its Relations to Job Performance and Turnover Intention. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostafin, B.; Robinson, M.; Meier, B. Handbook of Mindfulness and Self-Regulation; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Kibler, E.; Kautonen, T.; Munoz, P.; Wincent, J. Mindfulness and Taking Action to Start a New Business. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerup, C. Learning from Past Experience: Footnotes on Mindfulness and Habitual Entrepreneurship. Scand. J. Manag. 2005, 21, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelaia, N.; Reb, J. Improving Decision Making Through Mindfulness. In Mindfulness in Organizations: Foundations, Research, and Applications; Reb, J.W., Atkins, P.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The Dynamics of Proactivity at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Leroy, H. Methods of Mindfulness: How Mindfulness Is Studied in the Workplace. In Mindfulness in Organizations: Foundations, Research, and Applications; Reb, J.W., Atkins, P.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kudesia, R.S. Mindfulness and Creativity in the Workplace. In Mindfulness in Organizations: Foundations, Research, and Applications; Reb, J.W., Atkins, P.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, M.; Poh, Y.N.; Nolson, O.N. Mindfulness, socioemotional wealth, and environmental strategy of family businesses. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Plana-Farran, M.; Ros-Morente, A.; Joana, A.; Solé, S. Mindfulness and Next-Generation Members of Family Firms: A Source for Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, K.E.; Davis, J.A.; Hampton, M.M.; Lansberg, I. Generation to Generation: Life Cycle of the Family Business; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.; Haynes, K.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-Controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González Ramírez, M.; Landero Hernández, R. Escala de cansancio emocional (ECE) para estudiantes universitarios: Propiedades psicométricas en una muestra de México. Anales de Psicología 2007, 23, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P.; Taggar, S. Family influences on firms: An introduction. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Challenge versus Advantage in Family. Bus. Strateg. Organ. 2003, 1, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Luis, G.-M. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I.; Lester, R.; Cannella, A. Are Family Firms Really Superior Performers? J. Corp. Financ. 2007, 13, 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I.; Astrachan, J.H. Influence of Family Relationships on Succession Planning and Training: The Importance of Mediating Factors. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barroso, A.B.; Sanguino Galván, R.S.; Palacios, T.M.B. El enfoque basado en el conocimiento en las empresas familiares. Investig. Adm. 2012, 109, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M.; Tàpies, J.; Cappuyns, K. Comparison of Family and Nonfamily Business: Financial Logic and Personal Preferences. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, M.K.; Martín-Santana, J. La influencia de las relaciones intergeneracionales en la formación y el compromiso del sucesor: Efectos sobre el proceso de sucesión en la empresa familiar. Rev. Eur. Dir. Y Econ. Empresa 2010, 19, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon-Rouvinez, D.; Ward, J.L. Introduction and models. In Family Business; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Arijs, D.; Michiels, A. Mental Health in Family Businesses and Business Families: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskiewicz, P.; Heinrichs, K.; Rau, S.B.; Reay, T. To Be or Not to Be: How Family Firms Manage Family and Commercial Logics in Succession. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 781–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zellweger, T. Toward a Paradox Perspective of Family Firms: The Moderating Role of Collective Mindfulness of Controlling Families. In The Sage Handbook of Family Business, 1st ed.; Melin, L., Nordqvist, M., Sharma, P., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 648–655. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S. Reflections on the 2010 AMR Decade Award: Delivering on the promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Metallo, C.; Agrifolio, R.; Briganti, P.; Mercurio, L.; Ferrara, M. Entrepreneurial Behaviour and New Venture Creation: The Psychoanalytic Perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaver, K.G.; Scott, L.R. Person, Process, Choice: The Psychology of New Venture Creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 27, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.D.; Uy, M.A.; Baron, R.A. How do feelings influence effort? An empirical study of entrepreneurs’ affect and venture effort. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhomina, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and psychological traits: The moderating influence of supportive environment. J. Behav. Stud. Bus. 2010, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.; Stubberud, H.A. Elements of entrepreneurial orientation and their relationship to entrepreneurial intent. J. Entrep. Educ. 2014, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mccline, R.L.; Bhat, S.; Baj, P. Opportunity recognition: An exploratory investigation of a component of the entrepreneurial process in the context of the health care industry. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 25, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, C.M.; Katz, J.A. The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Small Business Performance: A Configurational Approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A.; Aliri, J.; Ulacia, I.; Soroa, G.; Balluerka, N.; Aritzeta, A.; Muela, A. Assessment of entrepreneurial orientation in vocational training students: Development of a new scale and relationships with self-efficacy and personal initiative. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.B.; Pohjola, M.; Kraus, S.; Jensen, S.H. Exploring relationships among proactiveness, risk-taking and innovation output in family and non-family firms. Cre. In. Man. 2014, 23, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation in family SMEs: Unveiling the (actual) impact of the Board of Directors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pressutti, M.; Ordorici, V. Linking entrepreneurial and market orientation to the SME’s performance growth: The moderating role of entrepreneurial experience and networks. Int. Entrep. Man. Jo. 2019, 15, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Duda, J.; Suder, M. Explaining SME performance with fsQCA: The role of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneur motivation, and opportunity perception. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Ng, H.P. The effects of entrepreneurial orientation and marketing information on the performance of SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A. New venture creation: Controversial perspectives and theories. Econ. Anal. 2015, 48, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Olugbola, A. Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and start-up success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L.F.; Brush, C.G.; Manolova, T.S.; Greene, P.G. Start-up Motivations and Growth Intentions of Minority Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus Manag. 2010, 48, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, J.; Pappas, E. Sources and outlets of stress among university students: Correlations between stress and unhealthy habits. Undergraduate Research. J. Hum. Sci. 2010, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Thomas, M.R.; Shanafelt, T.D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belle, M.A.; Antwi, C.; Ntim, S.; Affum-Osei, E.; Ren, J. Am I Gonna Get a Job? Graduating Students’ Psychological Capital, Coping Styles, and Employment Anxiety. J. Career Dev. 2021, 08948453211020124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.R.; Yousaf, O.; Vittersø, A.D.; Jones, L. Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: A systematic review. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Rubio, D.; Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Colomer-Carbonell, A.; Martínez-Brotóns, C.; Solé, S.; Escamilla, C.; Giménez-Fita, E.; Moreno, Y.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; et al. Testing the intermediary role of perceived stress in the relationship between mindfulness and burnout subtypes in a large sample of Spanish university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Driscoll, M.; Byrne, S.; Mc Gillicuddy, A.; Lambert, S.; Sahm, L.J. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions for health and social care undergraduate students—A systematic review of the literature. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, A.; Telletxea, S.; Mateo-Pérez, E.; Padoan, S.; Basabe, N. Social climate in university classrooms: A mindfulness-based educational intervention. Psych J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian-Wei, L.; Jung, L.M. Impact of mindfulness meditation intervention on academic performance. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2018, 55, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumell, A.; Chiang, E.P.; Koch, S.; Mangeloja, E.; Sun, J.; Pedussel, J. A cultural comparison of mindfulness and student performance: Evidence from university students in five countries. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2021, 37, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, L.; Bellingrath, S.; Von Stockhauser, L. Mindfulness Training for Improving Attention Regulation in University Students: Is It Effective? and Do Yoga and Homework Matter? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y. The Influence of Managerial Mindfulness on Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glomb, T.M.; Duffy, M.K.; Bono, J.E.; Yang, T. Mindfulness at work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 30, pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; López-Fernández, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Family Firm: Mapping the Field and Tracing a Path for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 318–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In Handbook of emotion regulation, 2nd ed.; Gross, J.J., Ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/zh/tool/81287/r-a-language-and-environment-for-statistical-computing (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Black, D.S.; Sussman, S.; Anderson Johnson, C.; Milam, J. Psychometric Assessment of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents. Assessment 2012, 19, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 210. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, A.B. LA Importancia de la Gestión del Conocimiento en el Espíritu Emprendedor de Las Empresas Familiares; Universidad de Extremadura: Badajoz, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Chisholm, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Cooper, J.L.; Eaton, J. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piñeiro-Sousa, J.; López-Cabarcos, M.A.; Romero-Castro, N.M.; Pérez-Pico, A.M. Innovation, entrepreneurship and knowledge in the business scientific field: Mapping the research front. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 115, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, A.N. Organisational Citizenship Behaviour of MBA students: The role of mindfulness and resilience. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family Business | Education Prospects | Self-Employment Prospects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | Uncertain | Yes | Uncertain | ||||

| Variable | M (Sd) | M (Sd) | d | M (Sd) | M (Sd) | d | M (Sd) | M (Sd) | d |

| Mindfulness | 24.7 (5.5) | 24.9 (4.8) | 0.04 | 24.8 (4.6) | 24.8 (5.8) | 0.00 | 24.22 (4.9) | 25.5 (4.6) | 0.26 |

| Professional concerns | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.9) | 0.28 | 3.7 (0.92) | 3.6 (0.74) | 0.06 | 3.66 (0.91) | 3.67 (0.79) | 0.02 |

| Personal concerns | 3.3 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.1) | 0.05 | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.3 (0.99) | 0.03 | 3.33 (1.15) | 3.24 (1.03) | 0.08 |

| Family Business | Education Prospects | Self-Employment Prospects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | Uncertain | Yes | Uncertain | |

| Mindfulness → Concerns | −0.13 | −0.11 | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.02 | −0.37 * |

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| χ2 | 48.82 | 59.01 | 48.16 | |||

| df | 39 | 39 | 38 | |||

| CFI | 0.968 | 0.935 | 0.961 | |||

| TLI | 0.954 | 0.906 | 0.942 | |||

| RMSEA | 0.051 | 0.080 | 0.058 | |||

| AIC | 4463 | 4313 | 4013 | |||

| Δχ2 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 2.54 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plana-Farran, M.; Blanch, À.; Solé, S. The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031376

Plana-Farran M, Blanch À, Solé S. The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031376

Chicago/Turabian StylePlana-Farran, Manel, Àngel Blanch, and Silvia Solé. 2022. "The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031376

APA StylePlana-Farran, M., Blanch, À., & Solé, S. (2022). The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031376