Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers

Abstract

:1. Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers

1.1. Purpose of the Study

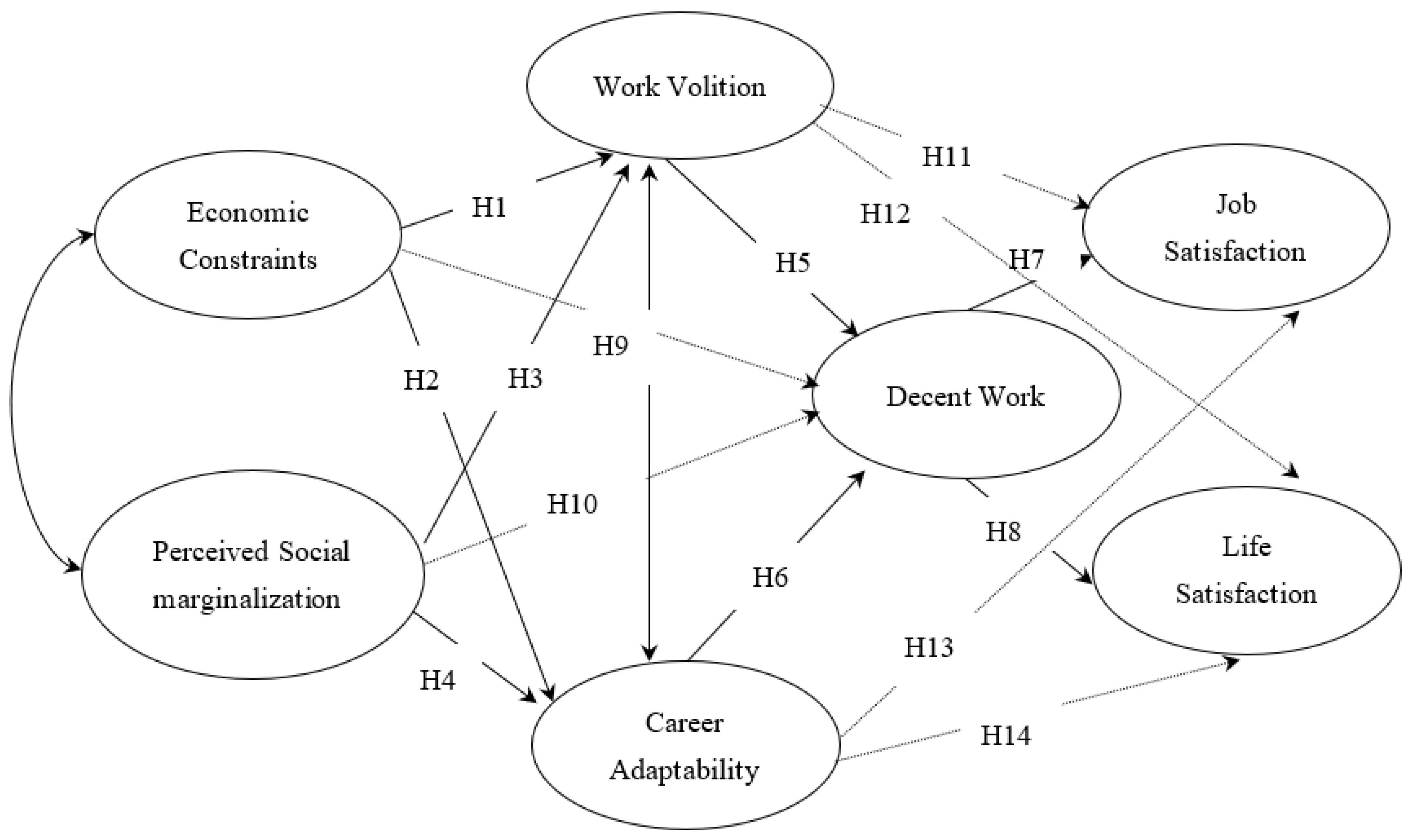

1.2. Hypothesized

1.2.1. Economic Constraints and Social Marginalization

1.2.2. Work Volition and Career Adaptability

1.2.3. Life and Job Satisfaction Are Outcomes of Decent Work

1.2.4. Economic Constraints, Social Marginalization, and Decent Work

1.2.5. Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction with Mediators

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Economic Constraints

2.2.2. Social Marginalization

2.2.3. Work Volition

2.2.4. Career Adaptability

2.2.5. Decent Work

2.2.6. Job Satisfaction

2.2.7. Life Satisfaction

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

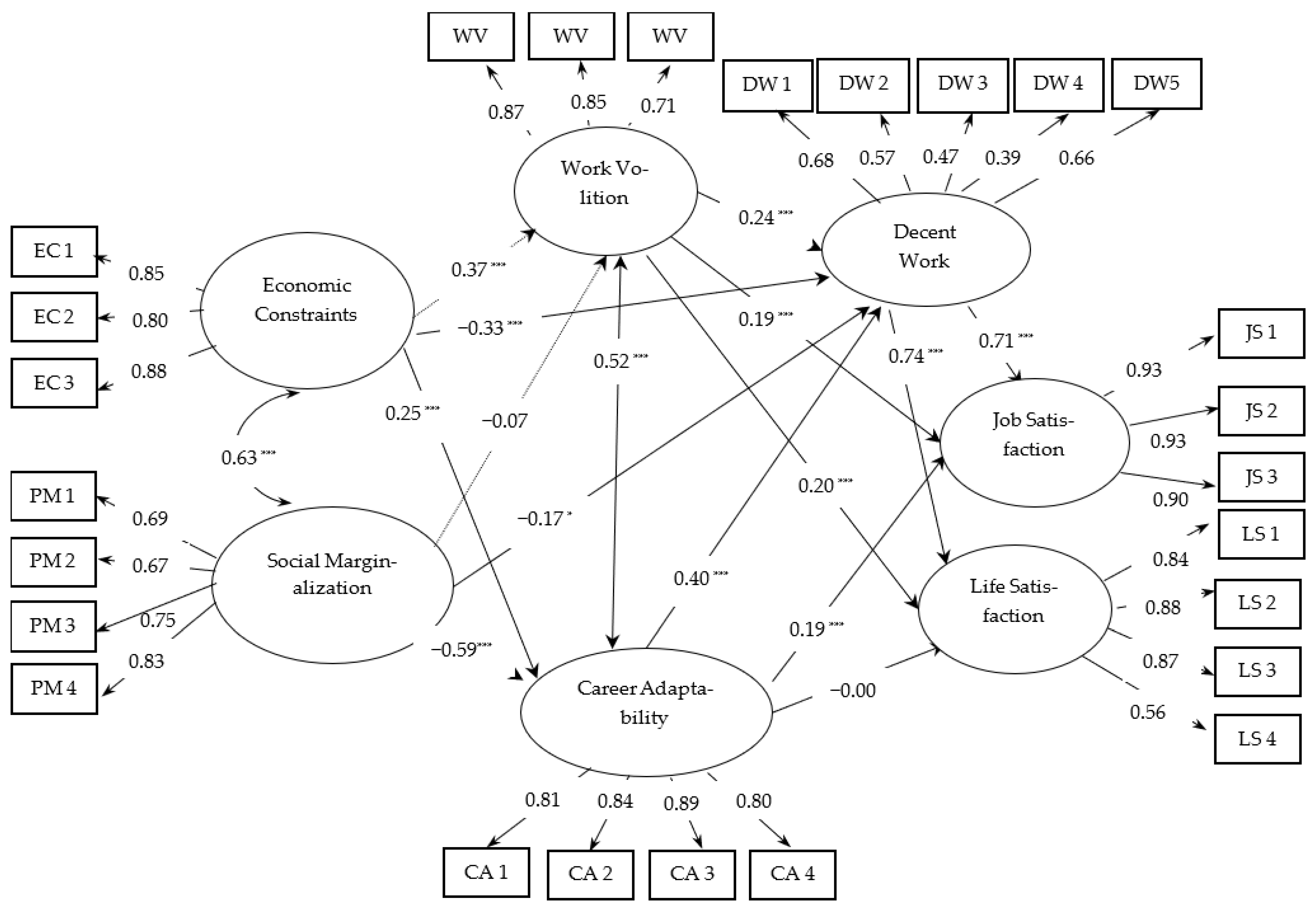

3.2. Test of the Hypothesized Model

Testing the Hypothesized Structural Model

3.3. Assessment of Mediated Effects

- a. (economic constraints × work volition × job satisfaction) = 0.070

- b. (economic constraints × career adaptability × job satisfaction) = 0.047

- c. (economic constraints × decent work × job satisfaction) = −0.227

- d. (economic constraints × work volition × decent work × job satisfaction) = 0.063

- e. (economic constraints × career adaptability × decent work × job satisfaction) = 0.071

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications and Recommendations for Career Counseling

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blustein, D.L. The role of work in psychological health and well-being: A conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blustein, D.L.; Masdonati, J.; Rossier, J. Psychology and the International Labor Organization: The Role of Psychology in the Decent Work Agenda. ILO White Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/research/publications/WCMS_561013/lang–en/index.htm (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Fouad, N.A. Work and vocational psychology: Theory, research, and applications. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J.L. Work and Psychological Health in APA Handbook of Counseling Psychology; Fouad, N.A., Carter, J.A., Subich, L.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Employment Outlook; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/employment-outlook/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Statistics Korea. Employment Trends 2021. Statistics South Korea Online Access. 2005. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C.; Santana, V.; Chairs, F. Employment Conditions and Health Inequalities. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) Employment Conditions Knowledge Network (EMCONET); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Byun, G.S.; Lee, H.W. The effects of job insecurity on mental health: The types of changes in employment status and the causal relationship between depression. J. Popul. Health Stud. 2018, 38, 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.H. An Empirical Analysis and Policy Task on the Decent Jobs of Young College Graduates. In Proceedings of the 2017 Employment Panel Conference. 2017. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjb9IOWvL31AhXFlFYBHRtUBh0QFnoECAMQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.kli.re.kr%2FdownloadEngPblFile.do%3FatchmnflNo%3D21038&usg=AOvVaw0mFUpDXw7wD7jwHWgk4RU5kr (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Paul, K.I.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.H. Social justice and counseling psychology. Korean Psychol. J. Couns. Psychother. 2018, 30, 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Seo, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. Career counseling and vocational counseling based on social justice. J. Korean Psychol. Soc. Couns. Psychother. 2018, 30, 515–540. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein, D.L.; Olle, C.; Connors-Kellgren, A.; Diamonti, A.J. Decent work: A psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duffy, R.D.; Blustein, D.L.; Diemer, M.A.; Autin, K.L. The psychology of working theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, O.G. A study on the ‘decent job’ movement of the working poor. Labor Policy Res. 2005, 5, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.B.; Lee, J.W. Comparison of the factors affecting the employment of decent jobs of college graduates. Community Stud. 2018, 26, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.H. Early job change and employment stability of the youth. Korea Youth Res. 2016, 27, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.K.; Kim, H.W. Analysis of the effects of job preparation activities on the good jobs of college graduates. Career Res. 2015, 5, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.H.; Shin, K.Y.; Song, R.R. An empirical analysis of polarization of job quality. Labor Policy Res. 2016, 16, 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Autin, K.; Bott, E. Work volition and job satisfaction: Examining the role of work meaning and person–environment fit. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Tebbe, E.A.; Bouchard, L.M.; Duffy, R.D. Access to decent and meaningful work in a sexual minority population. J. Career Assess. 2018, 27, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, R.P.; Velez, B.L.; Conlin, S.E.; Duffy, R.D.; England, J.W. Examining the psychology of working theory: Decent work among sexual minorities. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Kenna, A.C.; Gill, N.; DeVoy, J.E. The psychology of working: A new framework for counseling practice and public policy. Career Dev. Q. 2008, 56, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Schultheiss, D.E.P.; Flum, H. Toward a relational perspective of the psychology of careers and working: A social constructionist analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. Extending the reach of vocational psychology: Toward an inclusive and integrated psychology of working. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. A relational theory of working. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.A. The mediating effect of free will and career adaptability in daily life with constraints according to social class and academic background. Couns. Study 2019, 20, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.A.; Jeong, A.K. A theoretical review on Psychology of Working Theory and the implications for career counseling in South Korea. Korean J. Couns. 2019, 20, 207–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.R.; Lee, K.H. The differences of the effect of various levels of person-environment fit on job satisfaction. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2006, 19, 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. A model of counterproductive work behavior. In Counterproductive Workplace Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; Fox, S., Spector, P.E., Eds.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L.; Allan, B.A. Examining predictors of work volition among undergraduate students. J. Career Assess. 2016, 24, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanaviciute, I.; Pociute, B.; Kairys, A.; Liniauskaite, A. Perceived career barriers and vocational outcomes among university undergraduates: Exploring mediation and moderation effects. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, P.; Callahan, T.; Davis, T. The transition from college to work during the great recession: Employment, financial, and identity challenges. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, T.Y.; Par, E.H.; Ju, E.S. A Study on the influence of self-respect and social support on career decision among low-income adolescents in Korea. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2011, 31, 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F.; Ngo, H.Y.; Leung, A. Predicting work volition among undergraduate students in the United States and Hong Kong. J. Career Dev. 2018, 47, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; You, J.; Tang, Y. Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work Perception with Chinese Nursing College Stu-dents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozan, S.; Işık, E.; Blustein, D.L. Decent work and well-being among low-income Turkish employees: Testing the psychology of working theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autin, K.; Douglass, R.; Duffy, R.; England, J.; Allan, B. Subjective social status, work volition, and career adaptability: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Diemer, M.A.; Perry, J.C.; Laurenzi, C.; Torrey, C.L. The construction and initial validation of the Work Volition Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadidian, A.; Duffy, R.D. Work volition, career decision self-efficacy, and academic satisfaction: An examination of mediators and moderators. J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S., Lent, R., Eds.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tokar, D.M.; Kaut, K.P. Predictors of decent work among workers with Chiari malformation: An empirical test of the Psychology of Working Theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 106, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukgoze-Kavas, A.; Autin, K.L. Decent work in Turkey: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. From decent work to decent lives: Positive self and relational management (PSandRM) in the twenty-first century. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Autin, K.L.; Allan, B.A. Socioeconomic privilege and meaningful work: A psychology of working perspective. J. Career Assess. 2020, 28, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Hours Worked (Indicator). 2021. Available online: https://data.oecd.rog/em[/hours-worked.htm (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Cheon, B.Y. Korea’s Supply and Demand of Elderly Care Workers and Policies Improvement; Korean Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade: Sejong, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y. Analysis of the “Time Selective Job policy”: A comparative study on South Korea, Netherlands and Germany. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2014, 21, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.K. The tasks and limitations of permanent part-time work. J. Bus. Adm. Law 2016, 26, 511–548. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.J.; Ryu, S.J. Women’s time-selective jobs: Suggestions for work-family balance. Gend. Rev. 2015, 39, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, L.M.; Nauta, M.M. College students’ health and short-term career outcomes: Examining work volition as a mediator. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P.; Hoare, P.N.; Perera, H.N.; Kossen, C.; Mason, L.; Munday, S.; Alchin, C.; Creed, A.; McDonald, N. Decent Work’s Association with Job Satisfaction, Work Engagement, and Withdrawal Intentions in Australian Working Adults. J. Career Assess. 2020, 29, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.J.; Kim, W.L.; Kim, J.S. The effects of the meaning of life and the free will of work on the satisfaction of life of college students. Learn.-Cent. Study 2018, 18, 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Bott, E.M.; Torrey, C.L.; Webster, G.W. Work volition as a critical moderator in the prediction of job satisfaction. J. Career Assess. 2013, 21, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, M.; Bollmann, G.; Rossier, J. Exploring the path through which career adaptability increases job satisfaction and lowers job stress: The role of affect. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Jia, Y.; Hou, Z.-J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.-L. A test of psychology of working theory among Chinese urban workers: Examining predictors and outcomes of decent work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleyer, T.K.; Forrest, J.L. Methods for the design and administration of web-based surveys. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2000, 7, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kang, S.J. Study on the Effects of Economic Stress on the Psychological Well-Being of the College Students: Focusing on Social Activity Participation and Social Support as a Mediator. Master’s Dissertation, Baekseok University, Cheonan, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heitmeyer, W. Deutsche Zustande. Folge 7 [German States. Sequel 7]; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Issmer, C.; Wagner, U. Perceived marginalization and aggression: A longitudinal study with low-educated adolescents. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, J. Career adapt-abilities scale—Korea form: Psychometric properties and construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Allan, B.A.; England, J.W.; Blustein, D.L.; Autin, K.L.; Douglass, R.P.; Ferreira, J.; Santos, E.J.R. The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.S.; Kim, S.Y. Decent work in South Korea: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W.; Lofquist, L.H. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire; Industrial Relations Center, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.J. Validation Study of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ). Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.; Larsen, R.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.H.; Cha, K.H. Cross-Country Comparative Study on Quality of Life; Zipmundang: Seoul, Korea, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.W.; Kahn, J.H.; Spoth, R.; Altmaier, E.M. Analyzing data from experimental studies: A latent variable structural equation modeling approach. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 45, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Lomax, R.G. The Effect of Varying Degrees of Nonnormality in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2005, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Methodology in the Social Sciences. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Nonnormal Variables: Problems and Remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.Y. Exploring the possible direction of interpreting inconsistent mediational effect. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 39, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W. The Mediating Effect of Career-Related Parent Support in the Relations between Career Stress and Career Maturity, Economic Hardship and Career Maturity. Master’s Dissertation, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn, M.L.; Fagan, A.A.; Hawkins, J.D.; Oesterle, S. Effects of Communities That Care system on cross-sectional profiles of adolescent substance use and delinquency. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.H.; An, H.N. Mediating effects of achievement pressure and career decision-making self-efficacy on the relationships between parent-child bonding, parental socioeconomic status, and college students’ career decisions. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2014, 26, 657–682. [Google Scholar]

- England, J.W.; Duffy, R.D.; Gensmer, N.P.; Kim, H.J.; Buyukgoze-Kavas, A.; Larson-Konar, D.M. Women attaining decent work: The important role of workplace climate in psychology of working theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Kim, H.J.; Allan, B.A.; Prieto, C.G. Predictors of decent work across time: Testing propositions from Psychology of Working Theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 123, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Yong, H.W. The relation between career adaptability and job satisfaction, job burnout: Mediating effects of workplace spirituality. Couns. Stud. 2016, 17, 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, Y. Career adaptability, work engagement, and employee well-being among Chinese employees: The Role of Guanxi. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, K.; Lopez, F.G. Attachment security and career adaptability as predictors of subjective well-being among career transitioners. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Haase, R.; Santos, E.; Rabaça, J.A.; Figueiredo, L.; Hemami, H.G.; Almeida, L.M. Decent work in Portugal: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. The Psychology of Working: A New Perspective for A New Era. In Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of the Psychology of Working; Blustein, D.L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in A Time of Brilliant Technologies; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.S. To Get A “Good Job” Ten Years after Graduation; KRIVET Issue Brief: Sejong, Korea, 2019; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.K.; Lee, S.J. A meta-analysis of antecedent variables on career adaptability of undergraduate student. J. Employ. Career 2018, 8, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.Y.; Hwang, Y.J.; Lee, S.J.; Rosa, L. Research on the Status of Youth Part-Time Jobs and Policy Measures I; Research Report of the Korea Youth Policy Institute: Sejong, Korea, 2014; pp. 1–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y.J.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, S.J.; Byun, J.H. A Survey on the Actual Condition of Youth Part-Time Jobs and a Study on Policy Measures II; Korea Youth Policy Institute: Sejong, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zammitti, A.; Magnano, P.; Santisi, G. “Work and Surroundings”: A Training to Enhance Career Curiosity, Self-Efficacy, and the Perception of Work and Decent Work in Adolescents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.G.; Green, D.P.; Ha, S.E. Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (Don’t expect an easy answer). J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Pirlott, A.G. Statistical Approaches for Enhancing Causal Interpretation of the M to Y Relation in Mediation Analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 207 | 49.3 |

| Female | 213 | 50.7 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 177 | 42.1 |

| Married | 243 | 57.9 | |

| Education | High school grade | 84 | 20.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 282 | 67.2 | |

| Post graduate | 54 | 12.8 | |

| Occupation | Office job | 271 | 64.5 |

| Sales job | 14 | 3.3 | |

| Production worker | 29 | 6.9 | |

| Service job | 78 | 18.6 | |

| Professional job | 28 | 6.7 | |

| Year of employment | >1 | 11 | 2.6 |

| 1–3 | 112 | 26.7 | |

| 3–10 | 123 | 29.3 | |

| 10< | 174 | 41.4 | |

| Job position | Staff | 127 | 30.2 |

| Assistant manager | 117 | 27.9 | |

| Manager | 123 | 29.3 | |

| Director | 53 | 12.6 | |

| Monthly household income | >KRW 2 million | 41 | 9.8 |

| KRW 2.01–4 million | 155 | 36.9 | |

| KRW 4.01–6 million | 107 | 25.5 | |

| KRW 6.01–8 million | 79 | 18.8 | |

| KRW 8 million< | 38 | 9.0 | |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | - | ||||||||

| 2. Education | 0.16 *** | - | - | |||||||

| 3. Year of working | 0.54 *** | 0.07 | - | - | ||||||

| 4. Economic constraints | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.13 ** | - | ||||||

| 5. Marginalization | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.56 *** | - | |||||

| 6. Work volition | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.29 *** | 0.17 ** | - | ||||

| 7. Career adaptability | 0.09 | 0.12 * | 0.14 ** | −0.12 * | −0.37 *** | 0.35 *** | - | |||

| 8. Decent work | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.33 *** | −0.39 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.46 *** | - | ||

| 9. Job satisfaction | 0.14 ** | 0.08 | 0.15 ** | −0.20 *** | −0.35 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.69 *** | - | |

| 10. Life satisfaction | 0.03 | 0.10 * | 0.14 ** | −0.23 *** | −0.29 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.68 *** | - |

| M | 39.09 | 1.97 | 3.09 | 2.85 | 2.12 | 4.18 | 3.63 | 4.21 | 3.28 | 3.77 |

| SD | 9.30 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 1.27 |

| Skewness | −0.37 | 2.32 | −1.06 | −0.11 | 0.24 | 0.15 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.12 | −0.10 |

| Kurtosis | 0.52 | 0.93 | −0.41 | −0.50 | −0.43 | 0.74 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.30 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | 965.761 | 361 | p < 0.001 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.063 (0.058, 0.068) |

| Hypothesized model | 965.761 | 361 | p < 0.001 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.063 (0.058, 0.068) |

| Alternative model | 851.403 | 355 | p < 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.058 (0.053, 0.063) |

| Path | Standardized Total Effect | Standardized Direct Effect | Standardized Indirect Effect | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| economic constraints → career adaptability | 0.25 ** | 0.25 ** | - | |

| economic constraints → work volition | 0.37 ** | 0.37 ** | - | |

| economic constraints → (work volition) (career adaptability) → decent work | −0.14 | −0.33 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.10, 0.30 |

| economic constraints → (work volition) (career adaptability) (decent work) → job satisfaction | 0.02 | - | 0.02 | −0.14, 0.18 |

| economic constraints → (work volition) (career adaptability) (decent work) → life satisfaction | −0.03 | - | −0.03 | −0.19, 0.11 |

| social marginalization → career adaptability | −0.59 ** | −0.59 ** | - | |

| social marginalization → work volition | −0.07 | −0.07 | - | |

| social marginalization → (work volition) (career adaptability) → decent work | −0.42 ** | −0.17 | −0.25 ** | −0.39, −0.12 |

| social marginalization → (work volition) (career adaptability) (decent work) → job satisfaction | −0.42 ** | - | −0.42 ** | −0.57, −0.24 |

| social marginalization → (work volition) (career adaptability) (decent work) → life satisfaction | 0.33 ** | - | −0.33 ** | −0.47, −0.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.; Kim, J. Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031100

Kim M, Kim J. Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031100

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Minsun, and Jaehoon Kim. 2022. "Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031100

APA StyleKim, M., & Kim, J. (2022). Examining Predictors and Outcomes of Decent Work among Korean Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031100