Health Security, Quality of Life and Democracy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Approach in the EU-27 Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Healthcare Systems, Resilience and Coordinated Policies during COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-National Perspectives in EU-27

1.2. Human Development and Life Satisfaction: Challenges and Threats during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Design, Research Objectives and Hypotheses

2.2. Data, Methods and Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in EU-27 Countries

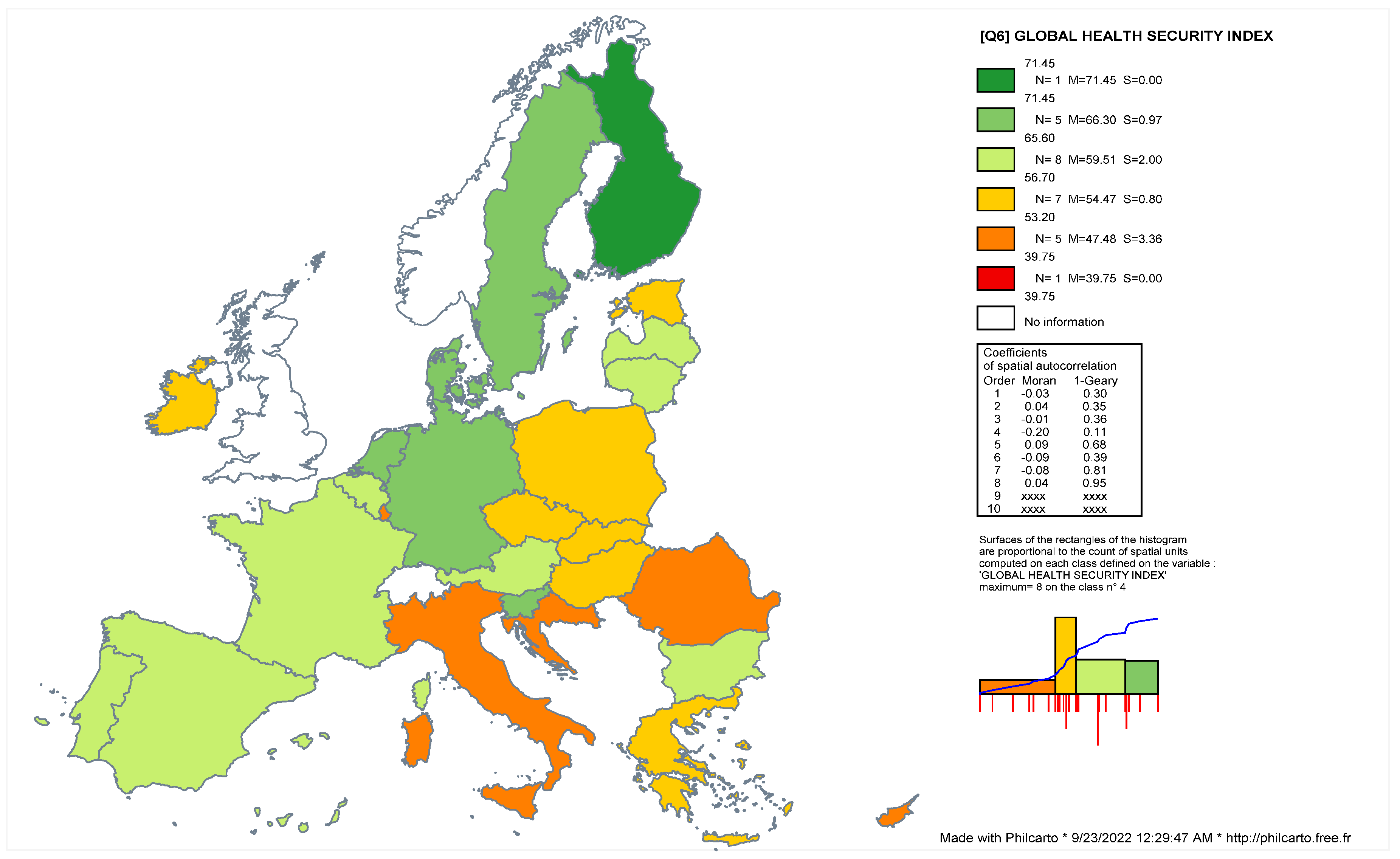

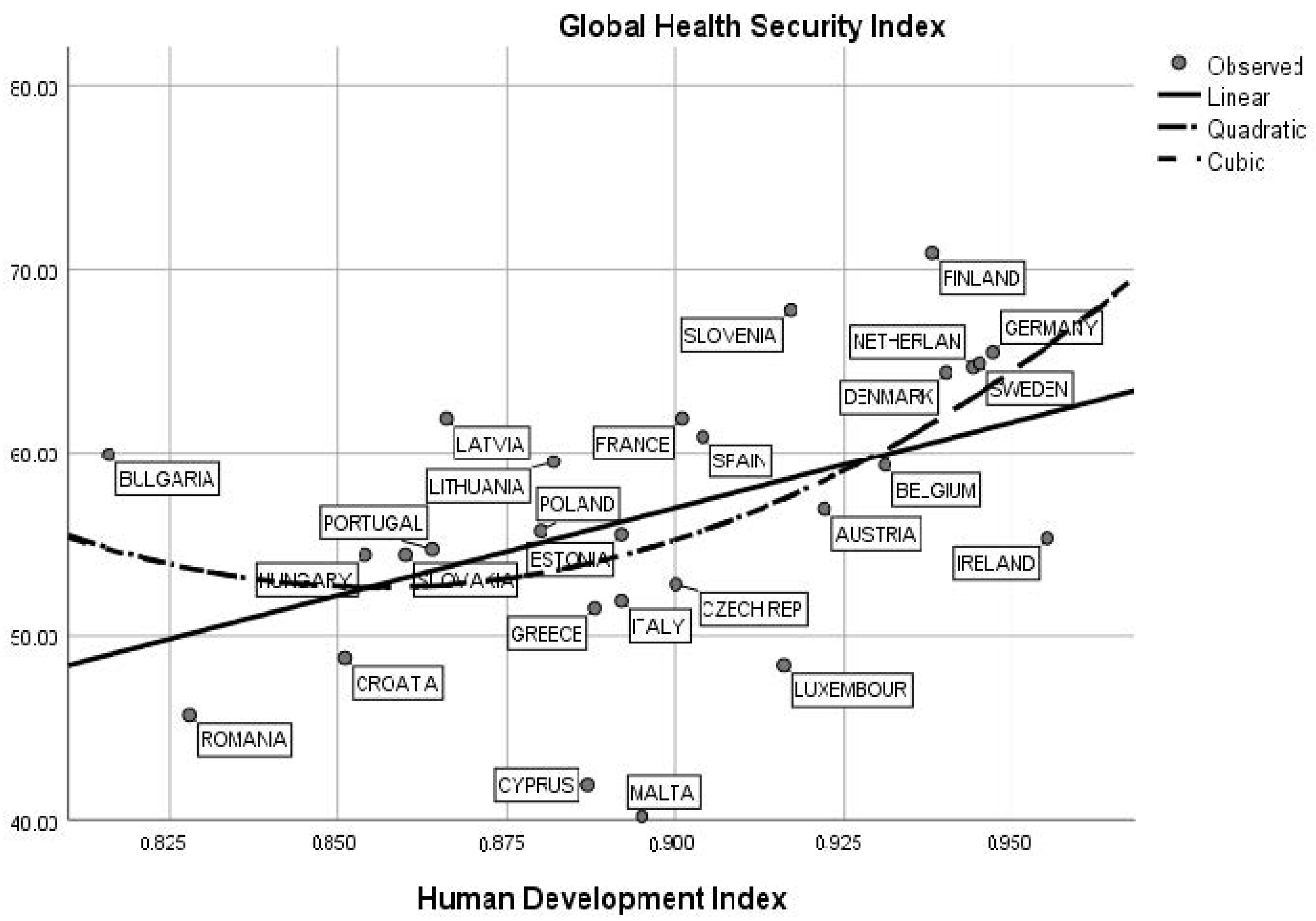

3.2. Health Security, Social Progress and Human Development: Challenges and Interactions during COVID-19 Pandemic

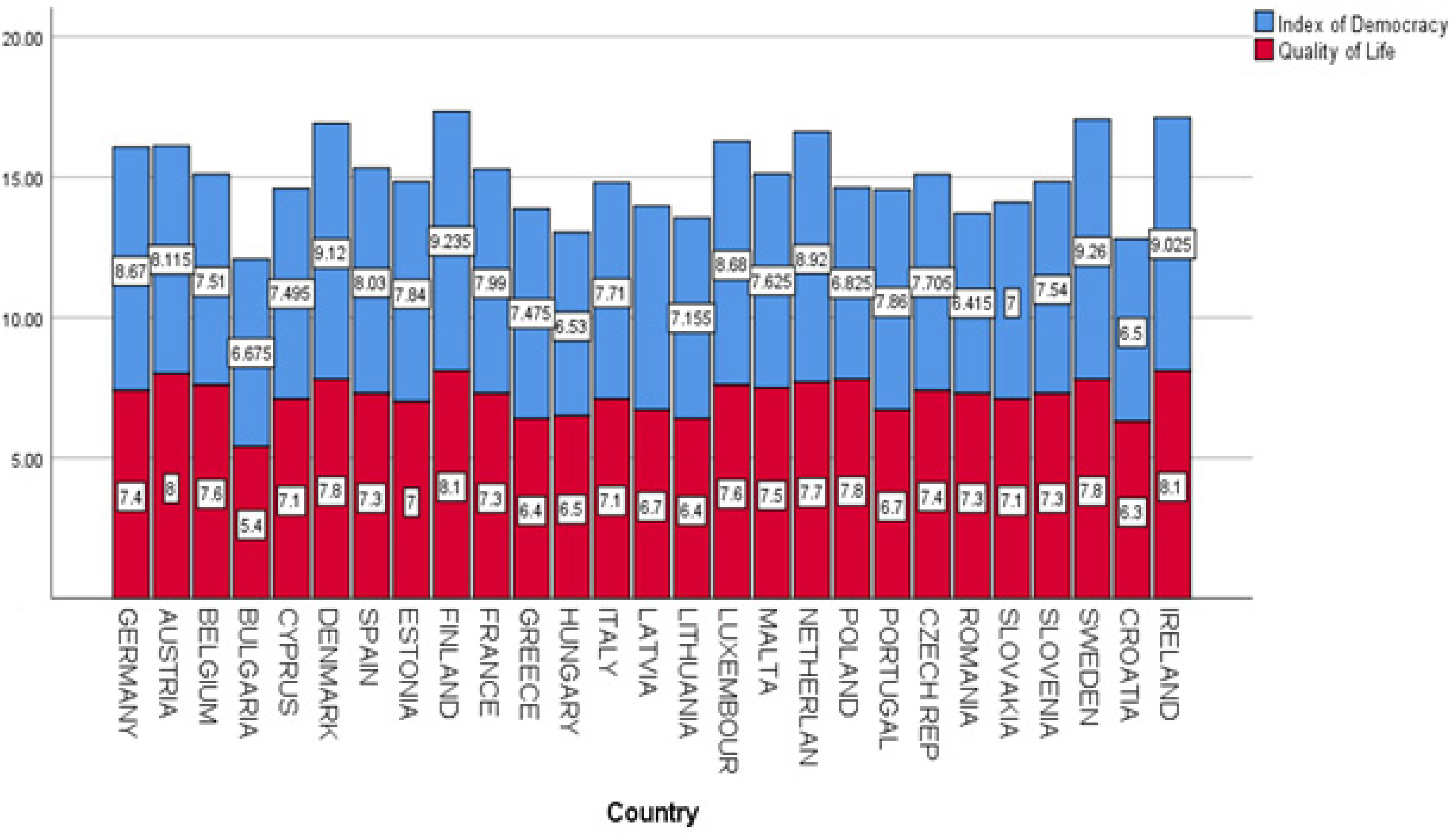

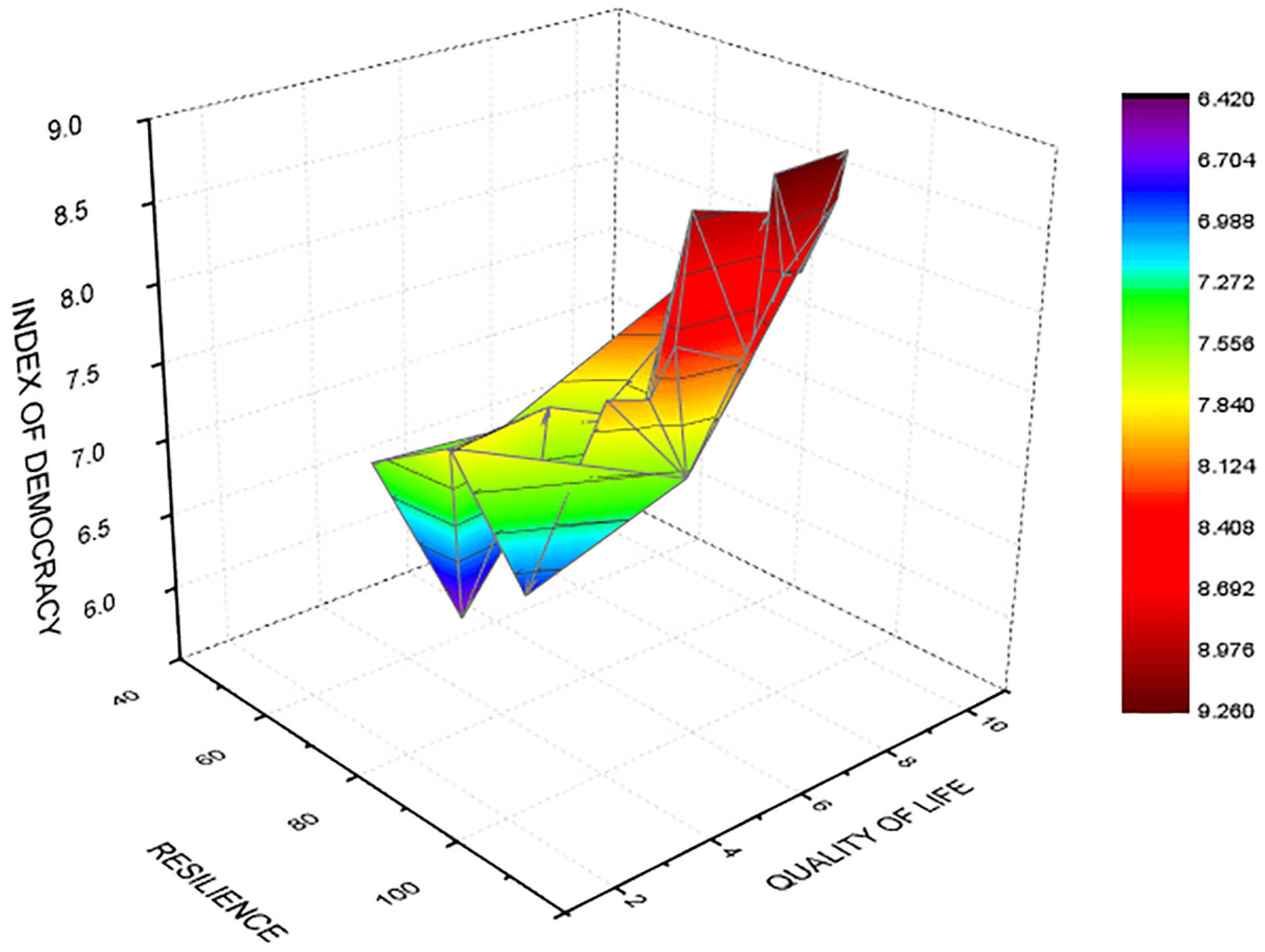

3.3. Quality of Life, Democracy and Resilience during Pandemic Times

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altig, D.; Baker, S.; Barrer, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Chen, S.; Davis, S.J.; Leather, J.; Meyer, B.; Mihaylov, E.; et al. Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppawittaya, P.; Yiemphat, P.; Yasri, P. Effects of Social Distancing Self-Quarantine and Self-Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on People’s Well-Being, and How to Cope with It. Int. J. Sci. Healthc. Res. 2020, 5, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.; di Mauro, B.W. Economics in the Time of COVID-19; CEPR Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sandeep, K.M.; Maheshwari, V.; Prabhu, J.; Prasanna, M.; Jayalakshmi, P.; Suganya, P.; Benjula, A.M. Social economic impact of COVID-19 outbreak in India. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2020, 16, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiner, M. The Future of Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Losonczy, L.I.; Barnes, S.L.; Liu, S.; Williams, S.R.; McCurdy, M.T.; Lemos, V.; Chandler, J.; Colas, L.N.; Augustin, M.E.; Papali, A.; et al. Critical care capacity in Haiti: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garces, A.; Baldassari, E.; Solomon, M. Homelessness and Coronavirus: What Bay Area Counties Are Doing—And How You Can Help. KQED News, 19 March 2020. Available online: https://www.kqed.org/news/11807409/coronavirus-what-bayarea-counties-are-doing-for-homeless-residents-and-how-you-can-help (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Shamasunder, S.; Holmes, M.S.; Goronga, T.; Carrasco, H.; Katz, E.; Frankfurter, R.; Keshavjee, S. COVID-19 reveals weak health systems by design: Why we must re-make global health in this historic moment. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, L.; Andreosso-O’Callaghan, B. COVID-19-Global Stock Markets “Black Swan”. Crit. Lett. Econ. Financ. 2020, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdell, C.A. Economic, social and political issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 68, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem Ashraf, B. Economic impact of government interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence from financial markets. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 27, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.D. Measuring employment during COVID 19: Challenges and opportunities. Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.; Grimshaw, D. A gendered lens on COVID-19 employment and social policies in Europe. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemelas, J.; Davison, J.; Keltner, C.; Ing, S. Inequities in Employment by Race, Ethnicity, and Sector during COVID-19. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Gozgor, G.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J. Employment hysteresis in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ. Res. 2021, 34, 3343–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, C.; Crane, L.; Decker, R.; Hamins-Puertolas, A.; Kurz, C. Tracking Labor Market Developments during the COVID19 Pandemic: A Preliminary Assessment; Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2020-030; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B.J.; Kyle, R.; Song, J.; Davies, A. Characteristics of those most vulnerable to employment changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative cross-sectional study in Wales. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 76, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.; Sreeganga, S.D.; Ramaprasad, A. Access to Healthcare during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhebin, W.; Yuqi, D.; Yinzi, J.; Zhi-Jie, Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: How countries should build more resilient health systems for preparedness and response. Glob. Health J. 2020, 4, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Willan, J.; John King, A.; Jeffery, K.; Bienz, N. Challenges for NHS hospitals during COVID-19 epidemic Healthcare workers need comprehensive support as every aspect of care is reorganized. BMJ 2020, 368, m1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S. COVID-19: Staff absences in July surged amid ongoing pressure on Hospitals. BMJ 2022, 378, o1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldane, V.; Morgan, T.G. From resilient to transilient health systems: The deep transformation of health systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Semenza, J.C. Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.B. Bouncing forward: Assessing advances in community resilience assessment, intervention, and theory to guide future work. Am. Beh. Sci. 2015, 59, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, A.P.; Fani, N.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J. Psychological resilience and neurocognitive performance in a traumatized community sample. Depr. Anx. 2010, 55, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, N.; Karayiannis, P.N.; Convie, L.; Clarke, M.; Kirk, S.J.; Campbell, W.J. Resilience in medical doctors: A systematic review. BMJ Postgrad. Med. J. 2019, 95, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrman, H.; Stewart, E.D.; Diaz-Granados, N.; Berger, L.E.; Jackson, B.; Yuen, T. What Is Resilience? Canad. J. Psych. 2011, 56, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, P.L.; Valle, F.; De Domenico, M. Proactive vs. reactive country responses to the COVID19 pandemic shock. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adly, M.H.; AlJahdali, A.I.; Garout, M.A.; Khafagy, A.A.; Saati, A.A.; Saleh, A.K. Correlation of COVID-19 Pandemic with Healthcare System Response and Prevention Measures in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Subirats, I.; Vargas, I.; Mogollón-Pérez, A.S.; De Paepe, P.; da Silva, M.R.; Unger, J.P.; Vázquez, M.L. Barriers in access to healthcare in countries with different health systems. A cross-sectional study in municipalities of central Colombia and north-eastern Brazil. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 106, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.; Vamos, S.; Okan, O. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Health Literacy Research Around the World: More Important Than Ever in a Time of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maior, P.; Camisão, I. The Pandemic Crisis and the European Union COVID-19 and Crisis Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.H.; Gossner, C.M.; Colzani, E.; Kinsman, J.; Alexakis, L.; Beauté, J.; Würz, A.; Tsolova, S.; Bundle, N.; Ekdah, K. Potential scenarios for the progression of a COVID-19 epidemic in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénassy-Quéré, A.; di Mauro, B.W. Europe in the time of COVID-19: A new crash test and a new opportunity. In Europe in Time of COVID-19; Bénassy-Quéré, A., di Mauro, B.W., Eds.; CEPR Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Mutchler, J.E. Older Adults and the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantrais, L.; Letablier, M.-T. Comparing and Contrasting the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the European Union; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Mckee, M.; Mossialos, E.; Abel-Smith, B. COVID-19 exposes weaknesses in European response to outbreaks. BMJ 2020, 368, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Health Security Index, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Global Health Security: 2021. Available online: https://www.ghsindex.org/about/ (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Rađenović, T.; Radivojević, V.; Krstić, B.; Stanišić, T.; Živković, S. The Efficiency of Health Systems in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the EU Countries. Probl. Sust. Dev. 2022, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, E.; Sbrogiò, L.G.; Di Rosa, E.; Cinquetti, S.; Francia, F.; Ferro, A. Italian Public Health Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Report from the Field, Insights and Challenges for the Department of Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, A.; Erondu, A.N.; Heymann, L.D.; Gitahi, G.; Yates, R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: Rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet 2021, 397, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzúrova, D.; Kvӗtoň, V. How health capabilities and government restrictions affect the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-country differences in Europe. Appl. Geograph. 2021, 135, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Hertelendy, J.A.; Goniewicz, M.; Naylor, K.; Burkle, F.M., Jr. Current Response and Management Decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.; Casady, C.B. Proactive and Strategic Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Epoch. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, H.; De Ruijter, A. The Health-Security Nexus and the European Union: Toward a Research Agenda. Eur. J. Risk Reg. 2017, 8, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowicz, I.; Rudawska, I. Struggling with COVID-19—A Framework for Assessing Health System Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, C.; Carpentieri, G. Quality of life in the urban environment and primary health services for the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application to the city of Milan (Italy). Cities 2021, 110, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, S.; Kizilkaya, M.; Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Romānova, I.; Dalli Gonzi, R.; Jakovljevic, M. A Country Pandemic Risk Exposure Measurement Mode. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2020, 13, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.; Clark, J.; Colombelli, A.; Corradini, C.; De Propris, L.; Derudder, B.; Fratesi, U.; Fritsch, M.; Harrison, J.; Hatfield, M.; et al. Regions in a time of pandemic. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Hill, M. The sustainability debate. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C.; Gibson, C. Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Rupani, P.F.; Rupani, M.M.; Kamyab, H.; Shao, W.; Ahmadi, H.; Aljojo, N. Measuring sustainability through ecological sustainability and human sustainability: A machine learning approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlaus, I.; Jacobs, G. Human Capital and Sustainability. Sustainability 2011, 3, 97–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, P. Incentivising employment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Theory Pract. Legis. 2020, 8, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Contextualizing COVID-19. In The COVID-19 Crisis. Social Perspectives; Deborah Lupton, D., Willis, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sakshaug, J.W.; Beste, J.; Coban, M.; Fendel, T.; Haas, G.C.; Hülle, S.; Kosyakova, Y.; König, C.; Kreuter, F.; Küfner, B.; et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Labor Market Surveys at the German Institute for Employment Research. Surv. Res. Methods 2020, 14, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Pantea, M.C. Precarity and Vocational Education and Training; Palgrave Macmillan; Springer International Publishing AG: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Human Development Index, United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2021–2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Ng Kam, M. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Pandemic Planning. Plan. Theor. Pract. 2020, 21, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, L.W.; Brandli, L.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Platje, J. COVID-19 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Threat to Solidarity or an Opportunity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, B.E.; Burgess, C.J. Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, Z.; Mazaheri, E.; Hasanpour-Dehkordi, A.; Pordanjani, S.R.; Naghibzadeh-Tahami, A.; Naemi, H.; Goodarzi, E. COVID-19 Pandemic in the World and its Relation to Human Development Index: A Global Study. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 15, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumbis, A.Y. Testing the socioeconomic determinants of COVID-19 pandemic hypothesis with aggregated Human Development Index. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denga, G.; Shib, J.; Lid, Y.; Liao, Y. The COVID-19 pandemic: Shocks to human capital and policy responses. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 5613–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkhel, M. The impact of the pandemic on human capital. Human capital index. Global. Bus. 2022, 13, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, W.H.; Mirza, T.; Mubasher, M.H. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Human Behavior. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Eng. 2020, 5, 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkar, P. Impact Of COVID-19 Pandemic on Education System. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 3812–3814. [Google Scholar]

- Shazia, R.; Yadav, S.S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education and Research. Ind. J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Martín, M.-A.; Castano-Martínez, M.-S.; Méndez-Picazo, M.T. Effects of the pandemic crisis on entrepreneurship and sustainable development. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Toman, M.A. Economic Development and Environmental Sustainability. New Policy Options; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Hamschmidt, J.; Sharma, S.; Starik, M. Sustainable Innovation and Entrepreneurship. New Perspectives in Research on Corporate Sustainability; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hák, T.; Moldan, B.; Dahl, A.L. Sustainability Indicators. A Scientific Assessment; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vitenu-Sackey, P.A.; Barf, R. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Global Economy: Emphasis on Poverty Alleviation and Economic Growth. Econ. Financ. Lett. 2021, 8, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarovaya, L.; Mirza, M.; Abaidi, J.; Hasnaoui, A. Human Capital efficiency and equity funds’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 71, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leunga, T.Y.; Sharmab, P.; Adithipyangkulc, P.; Hosie, P. Gender equity and public health outcomes: The COVID-19 experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Life Satisfaction, OECD, Better Life Index. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/austria/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Overall Life Satisfaction, Eurostat, Quality of Life. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/qol/index_en.html (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Prime, H.; Wade, M. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvani, A.; Perez, M.S.; Lew, A.A. New visions for sustainability during a pandemic towards sustainable wellbeing in a changing planet. Eur. J. Geogr. 2020, 11, 3, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E.; Nadeau, S.; Higgins, J.; Kehayia, E.; Poldma, T.; Saj, A.; De Guise, A. COVID-19 lockdowns’ effects on the quality of life, perceived health and well-being of healthy elderly individuals: A longitudinal comparison of pre-lockdown and lockdown states of well-being. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 99, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, M.S.; Andrei, F.; Mancini, G.; Agostini, F.; Piombo, M.A.; Spicuzza, V.; Riolo, M.; Lavanco, G.; Trombini, E.; La Grutta, S. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown Measures on Quality of Life among Italian General Population. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geirdal, A.Ø.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Related Health Factors of Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, G.; Panteli, M.; Leonidou, C. Coping with the invisible enemy: The role of emotion regulation and awareness in quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, F.D.; Hassan, S.-U.-N.; Alsaif, B.; Zrieq, R. Assessment of the Quality of Life during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonichini, S.; Tremolada, M. Quality of Life and Symptoms of PTSD during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, A.; Pietrzyka, K. The COVID-19 epidemic in Poland and its influence on the quality of life of university students (young adults) in the context of restricted access to public spaces. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgaš, F.; Petrovič, F. Quality of Life and Quality of Environment in Czechia in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Geogr. J. 2020, 72, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasar, K.S.; Karaman, E. Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peteet, J.R. COVID-19 Anxiety. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2203–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Ferrand, J.; Fried, J.; Robinson, K. Health Care Workers’ Mental Health and Quality of Life during COVID-19: Results from a Mid-Pandemic, National Survey. Psychol. Serv. 2021, 72, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.N.; Pereira, L.N.; Da Fé Brás, M.; Ilchuk, K. Quality of life under the COVID-19 quarantine. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, P.A.; Vega-Fernadez, G.; Gomez-Bruton, A.; Leyton, B.; Lera, L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teacher Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Study from before and during the Health Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, P.A.; Vega-Fernadez, G. Teacher Teleworking during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Association between Work Hours, Work–Family Balance and Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabacal, S.J. COVID-19 Impact on the Quality of Life of Teachers: A CrossSectional Study. Asian J. Public Opin. Res. 2020, 8, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, K.D.; Stedman, M.; Heald, A.H. Stay at Home, Protect the National Health Service, Save Lives”: A cost benefit analysis of the lockdown in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, J.M.; Schöley, J.; Kashnitsky, I.; Zhang, L.; Rahal, C.; Missov, T.; Mills, M.C.; Dowd, J.B.; Kashyap, R. Quantifying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic through life-expectancy losses: A population-level study of 29 countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Keshky, M.E.S.; Basyouni, S.S.; Al Sabban, A.M. Getting Through COVID-19: The Pandemic’s Impact on the Psychology of Sustainability, Quality of Life, and the Global Economy–A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 585897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, T.L.D. COVID-19 and Quality of Life: Twelve Reflections. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, S.; Harmacek, J.; Krylova, P.; Htltlch, M. 2022 Social Progress Index. Available online: https://www.socialprogress.org/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Democracy Index 2021. The China Challenge. The Economist Intelligence Unit. Democracy Index. Available online: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- World Bank. World Bank Data: GDP 2020–2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- FM Global. FM Global Resilience Index. Available online: https://www.fmglobal.com/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. World Countries. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Roback, P.; Legler, J. Beyond Multiple Linear Regression Applied Generalized Linear Models and Multilevel Models in R; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Symbol | Unit of Measurement | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index of Democracy | ID | [0–10] | Economist Intelligence Unit [101] |

| Human Development Index | HDI | [0–1] | United Nations Development Programme [58] |

| Quality of Life/Life Satisfaction | QL | [0–10] | Eurostat [77] OECD Better Life Index [76] |

| Global Health Security Index | GHS | [0–100] | Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security [38] |

| GDP/Capita | GDP | $/capita | World Bank [102] |

| Civil Liberties | CL | [0–10] | Economist Intelligence Unit [101] |

| Resilience Index | RI | [0–100] | FM Global [103] |

| Social Progress Index | SPI | [0–100] | Social Progress Imperative [100] |

| Confirmed COVID-19 cases (2020–2022) | Cov-19 | [0–n] | Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [104] |

| COVID-19 Death Rate (2020–2022) | DRC | [0–100} | Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [104] |

| Proportion of Population Fully Vaccinated | VR | [0–100] | Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [104] |

| Global Health Security Index | Index of Democracy | Human Development Index | Quality of Life | Resilience Index | Social Progress Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 39.75 | 6.42 | 0.82 | 3.00 | 60.80 | 78.41 | |

| Maximum | 71.45 | 9.26 | 0.96 | 10.00 | 100.00 | 92.26 | |

| Percentiles | 25 | 53.33 | 7.18 | 0.86 | 5.10 | 68.60 | 83.86 |

| 50 | 56.92 | 7.70 | 0.89 | 6.10 | 81.20 | 86.58 | |

| 75 | 64.76 | 8.58 | 0.93 | 8.10 | 92.35 | 89.26 | |

| Range | 31.70 | 2.85 | 0.14 | 7.00 | 39.20 | 13.85 | |

| Mean | 57.32 | 7.80 | 0.89 | 6.23 | 80.66 | 86.42 | |

| Median | 56.92 | 7.70 | 0.89 | 6.10 | 81.20 | 86.58 | |

| Std. Deviation | 7.92 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 1.90 | 12.06 | 3.70 | |

| Variance | 62.85 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 3.63 | 145.52 | 13.72 | |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 74.622 | 3.544 | 21.058 | 0.000 | |||

| GDP per capita | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.787 | −3.828 | 0.004 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 15.825 | 13.357 | 1.185 | 0.270 | |||

| GDP per capita | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.955 | −7.773 | 0.000 | 0.905 | 1.104 | |

| Democracy Index | 7.095 | 1.593 | 0.547 | 4.453 | 0.002 | 0.905 | 1.104 | |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | −9.435 | 2.392 | −3.944 | 0.001 | |||

| Democracy Index | 1.961 | 0.298 | 0.821 | 6.583 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | −9.641 | 2.138 | −4.508 | 0.000 | |||

| Democracy Index | 1.245 | 0.390 | 0.521 | 3.193 | 0.005 | 0.466 | 2.146 | |

| Resilience Index | 0.071 | 0.028 | 0.410 | 2.515 | 0.021 | 0.466 | 2.146 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Șoitu, C.T.; Grecu, S.-P.; Asiminei, R. Health Security, Quality of Life and Democracy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Approach in the EU-27 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114436

Șoitu CT, Grecu S-P, Asiminei R. Health Security, Quality of Life and Democracy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Approach in the EU-27 Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114436

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘoitu, Conțiu Tiberiu, Silviu-Petru Grecu, and Romeo Asiminei. 2022. "Health Security, Quality of Life and Democracy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Approach in the EU-27 Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114436

APA StyleȘoitu, C. T., Grecu, S.-P., & Asiminei, R. (2022). Health Security, Quality of Life and Democracy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparative Approach in the EU-27 Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114436