Investigating the Relationship between Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Chinese Generalist Teachers in Rural Primary Schools: A Serial Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Job Burnout Scale

2.2.2. Perceived Organizational Support Scale

2.2.3. Work Engagement Scale

2.2.4. Job Satisfaction Scale

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Measurement Model Test

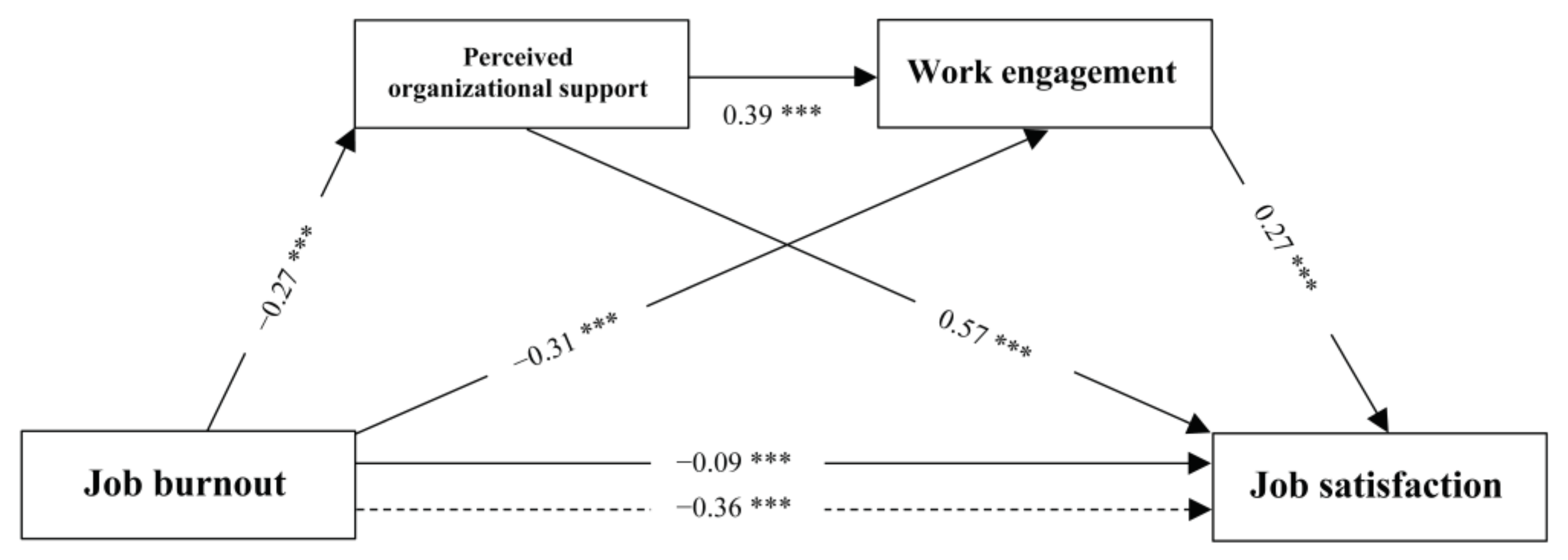

3.5. Structural Model Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The effect of Job Burnout on Job Satisfaction

4.2. The Mediation Role of Perceived Organizational Support

4.3. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

4.4. The Serial Mediating Role of Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A.E.; Albanese, B.J.; Shapiro, N.M.; Aarons, G.A. The roles of individual and organizational factors in burnout among community-based mental health service providers. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalvia, A.; Bonetto, C.; Bertani, M.; Bissoli, S.; Cristofalo, D.; Marrella, G.; Ceccato, E.; Cremonese, C.; De Rossi, M.; Lazzarotto, L.; et al. Influence of perceived organisational factors on job burnout: Survey of community mental health staff. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyer, K.; Berk, A.; Polatc, S. Does the Perceived Organizational Support Reduce Burnout? A Survey on Turkish Health Sector. Int. J. Bus. Adm. Manag. Res. 2016, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, C. The Influence of Perceived Organizational Support on Police Job Burnout: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, F.A.; Alsubaie, S.S.; Nasaani, A.A. Why So Cynical? The Effect of Job Burnout as a Mediator on the Relationship Between Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Cynicism. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 13, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.S.; Safdar, U. The Influence of Job Burnout on Intention to Stay in the Organization: Mediating Role of Affective Commitment. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 4016–4025. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, C.S.; Loong, D.; Bonato, S.; Thanh, N.X.; Jacobs, P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Ge, H. The status of job burnout and its influence on the working ability of copper-nickel miners in Xinjiang, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial & Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.C., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1279–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn. Stud. Vocat. Rehabil. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw, D.; Ditlopo, P.; Maseko, F.; Chirwa, M.; Mwisongo, A.; Bidwell, P.; Thomas, S.; Normand, C. Comparing the job satisfaction and intention to leave of different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 19287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, S.N. The relationship between burnout and job satisfaction in nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 1987, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouleau, D.; Fournier, P.; Philibert, A.; Mbengue, B.; Dumont, A. The effects of midwives’ job satisfaction on burnout, intention to quit and turnover: A longitudinal study in Senegal. Hum. Resour. Health 2012, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Sang, X.; Yuan, B. Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among primary care providers in rural China: Results from structural equation modeling. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout and job satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, H.K.; Harris, S.L.; Mesibov, G.B. Commitment to Philosophy, Teacher Efficacy, and Burnout Among Teachers of Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Liao, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W.; Ding, W. The Relationship Between Teacher Job Stress and Burnout: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 784243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platsidou, M. Trait Emotional Intelligence of Greek Special Education Teachers in Relation to Burnout and Job Satisfaction. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2010, 31, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhai, X.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q. The Effect of Work Stress on Job Burnout Among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Self-efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 122, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anomneze, E.A.; Ugwu, D.I.; Enwereuzor, I.K.; Ugwu, L.I. Teachers’ Emotional Labour and Burnout: Does Perceived Organizational Support Matter? Asian Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, F. The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between job stress and burnout: A mediating or moderating role? Curr. Psychol. 2018, 40, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faskhodi, A.A. Dimensions of Work Engagement and Teacher Burnout: A Study of Relations among Iranian EFL Teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 43, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, J.; Choi, S. Sources of social support, job satisfaction, and quality of life among childcare teachers. Soc. Sci. J. 2017, 54, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, A.S.; Justice, L.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E. Sense of School Community for Preschool Teachers Serving At-Risk Children. Early Educ. Dev. 2008, 19, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubibi, M.; Fute, A.; Xiao, W.; Sun, B.; Zhou, Y. Perceived Organizational Support and Career Satisfaction among Chinese Teachers: The Mediation Effects of Job Crafting and Work Engagement during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, W.; Zheng, W.; Huang, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Fang, G.; Zhao, X.; et al. Association Between Social Support and Job Satisfaction Among Mainland Chinese Ethnic Minority Kindergarten Teachers: The Mediation of Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulaziz, A.; Bashir, M.; Alfalih, A.A. The impact of work-life balance and work overload on teacher’s organizational commitment: Do Job Engagement and Perceived Organizational support matter. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9641–9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Qian, J.; Liu, H. The Relationship Between Preschool Inclusive Education Teachers’ Organizational Support and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of Teacher Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 900835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høigaard, R.; Giske, R.; Sundsli, K. Newly qualified teachers’ work engagement and teacher efficacy influences on job satisfaction, burnout, and the intention to quit. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasurdin, A.M.; Ling, T.C.; Khan, S.N. Linking Social Support, Work Engagement and Job Performance in Nursing. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Marcionetti, J.; Castelli, L. The job and life satisfaction of teachers: A social cognitive model integrating teachers’ burnout, self-efficacy, dispositional optimism, and social support. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross Francis, D.; Hong, J.; Liu, J.; Eker, A. Identity. In Research on Teacher Identity; Schutz, P., Hong, J., Cross Francis, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.; Smith, K. Science that Matters: Exploring Science Learning and Teaching in Primary Schools. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 41, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- King, F. Music Activities Delivered by Primary School Generalist Teachers in Victoria: Informing Teaching Practice. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 43, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, J.; Aquino Zúñiga, S.P.; García Martínez, V. Foreign language education in rural schools: Struggles and initiatives among generalist teachers teaching English in Mexico. Stud. Second. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2021, 11, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, J.H.; Mertala, P.-O. The Meaningful Memories of Visual Arts Education for Preservice Generalist Teachers: What is Remembered, Why, and from Where? Int. J. Educ. Arts 2020, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, L.; Bowles, R.; Ní Chróinín, D. Playing to our strengths: Generalist teachers’ experiences of class swapping for primary physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 26, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P. Generalist Elementary Male Teachers Advocating for Dance and Male Dancers. In Masculinity, Intersectionality and Identity: Why Boys (Don’t) Dance; Risner, D., Watson, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, L.; Bowles, R.; Ní Chróinín, D. Follow the leader? Generalist primary school teachers’ experiences of informal physical education leadership. Education 3-13 2020, 49, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D. Fostering a happy positive learning environment for generalist pre-service teachers: Building confidence that promotes wellbeing. Brit. J. Music Educ. 2019, 36, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, J.L.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.; Tucker, L. Representing sources of error in the common-factor model: Implications for theory and practice. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Preacher, K.J.; Hong, S. Sample Size in Factor Analysis: The Role of Model Error. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, A.; Whipp, P.R.; McSporran, G.; Teo, T. An interventional study with the Maldives generalist teachers in primary school physical education: An application of self-determination theory. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloviita, T.; Pakarinen, E. Teacher burnout explained: Teacher-, student-, and organisation-level variables. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.S.; Polychroni, F.; Vlachakis, A.N. Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N.C.; Sreckovic, M.A.; Lane, K.L. Special Education Teacher Burnout: A Synthesis of Research from 1979 to 2013. Educ. Treat. Child 2014, 37, 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Guay, F.; Senécal, C.; Austin, S. Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U.; Kunter, M.; Trautwein, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Baumert, J. Engagement and Emotional Exhaustion in Teachers: Does the School Context Make a Difference? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raducu, C.M.; Stanculescu, E. Personality and socio-demographic variables in teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.S.; Raquib, M.; Arif, I. The relationship between high performance work systems and proactive behaviors: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 314–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Wan, F. Social support and job satisfaction: Elaborating the mediating role of work-family interface. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Carlson, D.; Zivnuska, S.; Whitten, D. Support at work and home: The path to satisfaction through balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C. Organizations and supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Minor, K.I.; Wells, J.B.; Hogan, N.L. Social support’s relationship to correctional staff job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, M.-Y.; Harrison, D.F. Role Stressors, burnout, mediators, and job satisfaction: A stress-strain-outcome model and an empirical test. Soc. Work Res. 1998, 22, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Cosano-Rivas, F. Burnout, workplace support, job satisfaction and life satisfaction among social workers in Spain: A structural equation model. Int. Soc. Work 2011, 56, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero Jurado, M.d.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Atria, L.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Burnout, Perceived Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction: Perception of the Educational Context in High School Teachers. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1021408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinidad, J.E. Teacher satisfaction and burnout during COVID-19: What organizational factors help? Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.S.; Ho, S.K.; Ip, F.F.L.; Wong, M.W.Y. Self-Efficacy, Work Engagement, and Job Satisfaction Among Teaching Assistants in Hong Kong’s Inclusive Education. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402094100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, B. Confronting the challenge: The impact of whole-school primary music on generalist teachers’ motivation and engagement. Res. Stud. Music. Educ. 2019, 41, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Borrego-Alés, Y. Social support and engagement as antecedents of job satisfaction in nursing staff. Enferm. Glob. 2017, 16, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambidez-Ramos, A.; de Almeida, H. Work engagement, social support, and job satisfaction in Portuguese nursing staff: A winning combination. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 36, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Sub−Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 294 | 46.0% |

| Female | 345 | 54.0% | |

| Age | 20–30 | 53 | 8.3% |

| 31–40 | 186 | 29.1% | |

| 41–50 | 318 | 49.8% | |

| Over 50 | 82 | 12.8% | |

| Experience | 1–5 years | 54 | 8.5% |

| 6–10 years | 32 | 5.0% | |

| 11–20 years | 180 | 28.2% | |

| Over 20 years | 373 | 58.3% | |

| Degree | Master’s | 8 | 1.3% |

| Bachelor’s | 526 | 82.2% | |

| College | 97 | 15.2% | |

| Second vocational school | 8 | 1.3% | |

| Title | Associate professor | 1 | 0.2% |

| Senior | 419 | 65.5% | |

| Junior | 167 | 26.2% | |

| None | 52 | 8.1% | |

| Affiliation | Public | 625 | 97.8% |

| Private | 14 | 2.2% | |

| Contract | Long-term | 616 | 96.4% |

| Fixed-term | 23 | 3.6% |

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job burnout | 0.60 | 5.87 | 2.22 | 0.98 |

| Emotional exhaustion | 1.00 | 7.00 | 3.13 | 1.34 |

| Depersonalization | 1.00 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 1.22 |

| Low personal accomplishment | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.60 | 1.41 |

| Perceived organizational support | 1.25 | 5.00 | 3.63 | 0.59 |

| Work engagement | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.39 | 0.92 |

| Activity | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.36 | 0.94 |

| Dedication | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.68 | 1.05 |

| Absorption | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.18 | 1.05 |

| Job satisfaction | 2.15 | 5.00 | 3.71 | 0.51 |

| Intrinsic satisfaction | 2.33 | 5.00 | 3.80 | 0.51 |

| Extrinsic satisfaction | 1.63 | 5.00 | 3.58 | 0.58 |

| Variables | Gender | Age (Years) | Experience (Years) | Degree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 294) | Female (n = 345) | t | Sig. | 20–30 (n = 53) | 31–40 (n = 186) | 41–50 (n = 318) | 50 above (n = 82) | F | Sig. | 1–5 (n = 54) | 6–10 (n = 32) | 11–20 (n = 180) | 20 above (n = 373) | F | Sig. | Master (n = 8) | Bachelor (n = 526) | College (n = 97) | SVS (n = 8) | F | Sig. | |||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | M | SD | M | SD | M | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||||||

| JB | 2.37 | 1.01 | 2.08 | 0.93 | 3.73 | 0.00 *** | 2.91 | 0.88 | 2.17 | 0.98 | 2.13 | 0.94 | 2.21 | 1.00 | 10.46 | 0.00 *** | 2.85 | 0.94 | 2.34 | 0.91 | 2.16 | 0.96 | 2.14 | 0.96 | 8.88 | 0.00 *** | 2.58 | 1.39 | 2.20 | 0.96 | 2.22 | 1.04 | 2.57 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| POS | 3.57 | 0.61 | 3.69 | 0.57 | −2.50 | 0.01 * | 3.52 | 0.57 | 3.78 | 0.63 | 3.61 | 0.55 | 3.46 | 0.59 | 7.01 | 0.00 *** | 3.50 | 0.60 | 3.82 | 0.63 | 3.71 | 0.60 | 3.60 | 0.57 | 3.63 | 0.00 *** | 3.86 | 0.60 | 3.65 | 0.58 | 3.52 | 0.64 | 3.39 | 0.82 | 2.31 | 0.08 |

| WE | 5.29 | 0.93 | 5.48 | 0.91 | −2.57 | 0.01 * | 4.84 | 0.73 | 5.44 | 0.92 | 5.44 | 0.93 | 5.43 | 0.92 | 7.01 | 0.00 ** | 4.87 | 0.78 | 5.35 | 0.77 | 5.41 | 0.98 | 5.45 | 0.91 | 6.42 | 0.02 * | 5.73 | 1.20 | 5.39 | 0.90 | 5.37 | 1.00 | 4.93 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.39 |

| JS | 3.71 | 0.53 | 3.72 | 0.48 | −0.35 | 0.73 | 3.48 | 0.52 | 3.77 | 0.53 | 3.73 | 0.48 | 3.69 | 0.51 | 4.50 | 0.00 *** | 3.51 | 0.55 | 3.76 | 0.48 | 3.72 | 0.53 | 3.74 | 0.48 | 3.30 | 0.01 * | 4.14 | 0.69 | 3.72 | 0.49 | 3.68 | 0.56 | 3.38 | 0.57 | 3.29 | 0.02 * |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Job burnout | (0.88) | |||||||||||

| 2. Emotional Exhaustion | 0.73 ** | (0.90) | ||||||||||

| 3. Depersonalization | 0.77 ** | 0.65 ** | (0.91) | |||||||||

| 4. Low personal accomplishment | 0.71 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.24 ** | (0.90) | ||||||||

| 5. Perceived organizational support | −0.35 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.22 ** | (0.85) | |||||||

| 6. Work engagement | −0.49 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.45 ** | 0.38 ** | (0.95) | ||||||

| 7. Activity | −0.44 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.40 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.92 ** | (0.88) | |||||

| 8. Dedication | −0.49 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.41 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.90 ** | 0.76 ** | (0.91) | ||||

| 9. Absorption | −0.43 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.92 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.74 ** | (0.90) | |||

| 10. Job satisfaction | −0.46 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.35 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.59 ** | (0.94) | ||

| 11. Intrinsic satisfaction | −0.48 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.41 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.96 ** | (0.91) | |

| 12. Extrinsic satisfaction | −0.38 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.92 ** | 0.77 ** | (0.88) |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job burnout | Emotional exhaustion 5 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.64 |

| Depersonalization 6 | 0.87 | ||||

| Depersonalization 7 | 0.88 | ||||

| Depersonalization 8 | 0.82 | ||||

| Lack of Personal Accomplishment 13 | 0.61 | ||||

| Perceived organizational support | Perceived organizational support 1 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.65 |

| Perceived organizational support 2 | 0.84 | ||||

| Perceived organizational support 3 | 0.84 | ||||

| Perceived organizational support 6 | 0.76 | ||||

| Perceived organizational support 8 | 0.78 | ||||

| Work engagement | Activity 1 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.59 |

| Activity 2 | 0.79 | ||||

| Activity 3 | 0.76 | ||||

| Activity 5 | 0.71 | ||||

| Dedication 7 | 0.82 | ||||

| Dedication 8 | 0.83 | ||||

| Dedication 9 | 0.83 | ||||

| Dedication 10 | 0.81 | ||||

| Dedication 11 | 0.71 | ||||

| Absorption 12 | 0.76 | ||||

| Absorption 13 | 0.73 | ||||

| Absorption 14 | 0.75 | ||||

| Absorption 15 | 0.83 | ||||

| Absorption 16 | 0.72 | ||||

| Absorption 17 | 0.72 | ||||

| Job satisfaction | Intrinsic 11 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| Intrinsic 15 | 0.80 | ||||

| Intrinsic 16 | 0.80 | ||||

| Intrinsic 20 | 0.77 | ||||

| Extrinsic 5 | 0.81 | ||||

| Extrinsic 6 | 0.79 | ||||

| Extrinsic 12 | 0.84 | ||||

| Extrinsic 19 | 0.78 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Job burnout | − | ||

| 2. Perceived organizational support | 0.30 | − | |

| 3. Work engagement | 0.43 | 0.51 | − |

| 4. Job satisfaction | 0.39 | 0.81 | 0.62 |

| Fit Index | SRMR | d_ULS | d_G | NFI | RMS_theta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed value | <0.10 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.80 | <0.12 |

| Estimated value | 0.07 | 2.54 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.11 |

| Hypotheses | Path | β | t | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | JB −> JS | −0.09 | –3.04 *** | Supported |

| H2a | JB → POS | −0.27 | –6.48 *** | Supported |

| H2b | JB → WE | −0.31 | –8.10 *** | Supported |

| H3 | POS → JS | 0.57 | 18.89 *** | Supported |

| H4 | WE → JS | 0.27 | 8.16 *** | Supported |

| H5 | JB → POS → JS | −0.15 | –6.21 *** | Supported |

| H6 | JB → WE → JS | −0.09 | –5.70 *** | Supported |

| H7 | JB → POS → WE −> JS | −0.03 | –4.77 *** | Supported |

| Total effect | −0.36 | –8.87 *** | Supported | |

| Total indirect effect | −0.26 | –8.75 *** | Supported | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, W.; Wu, S. Investigating the Relationship between Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Chinese Generalist Teachers in Rural Primary Schools: A Serial Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114427

Chen W, Zhou S, Zheng W, Wu S. Investigating the Relationship between Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Chinese Generalist Teachers in Rural Primary Schools: A Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114427

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wei, Shuyi Zhou, Wen Zheng, and Shiyong Wu. 2022. "Investigating the Relationship between Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Chinese Generalist Teachers in Rural Primary Schools: A Serial Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114427

APA StyleChen, W., Zhou, S., Zheng, W., & Wu, S. (2022). Investigating the Relationship between Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Chinese Generalist Teachers in Rural Primary Schools: A Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114427