Application of McGuire’s Model to Weight Management Messages: Measuring Persuasion of Facebook Posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U Trial for Young Adults Attending University in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Selection Criteria

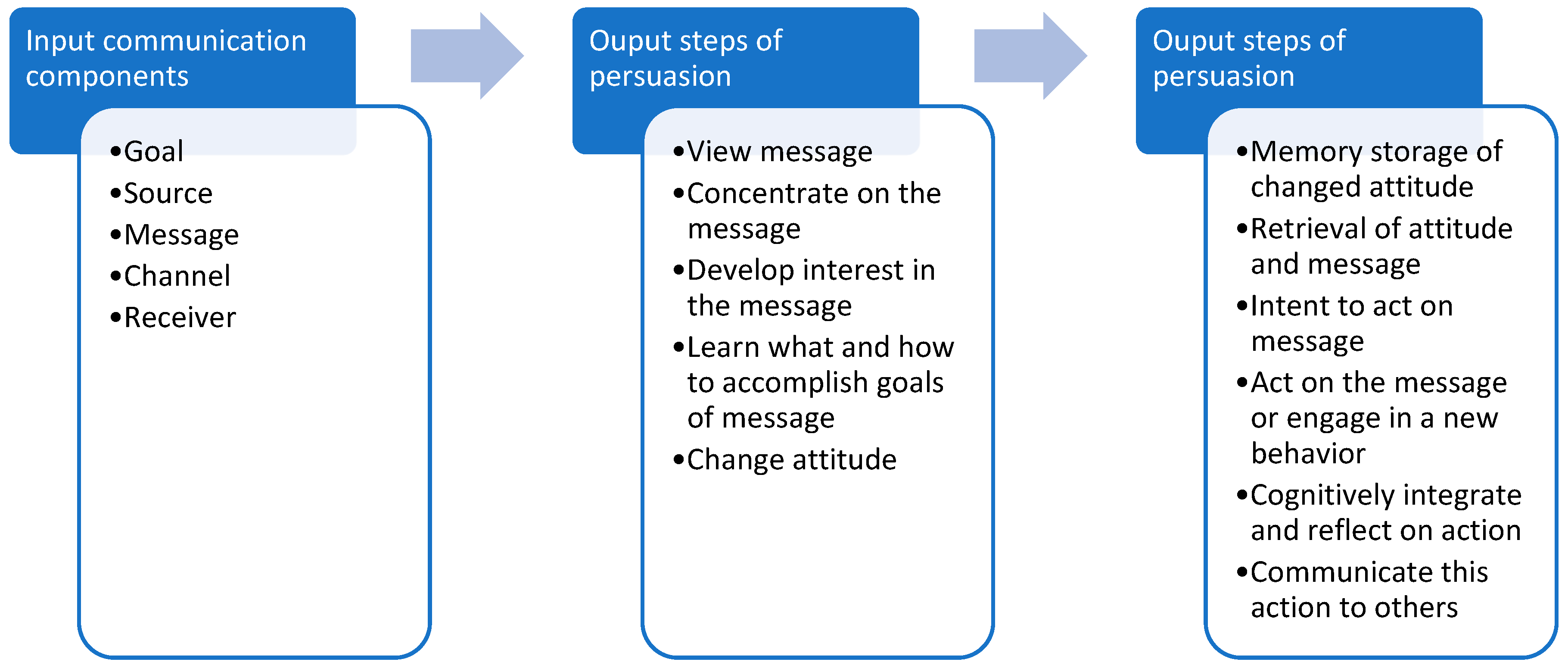

2.3. Framework

2.4. Input Variables

2.5. Coding Plan

2.6. Analysis Plan

3. Results

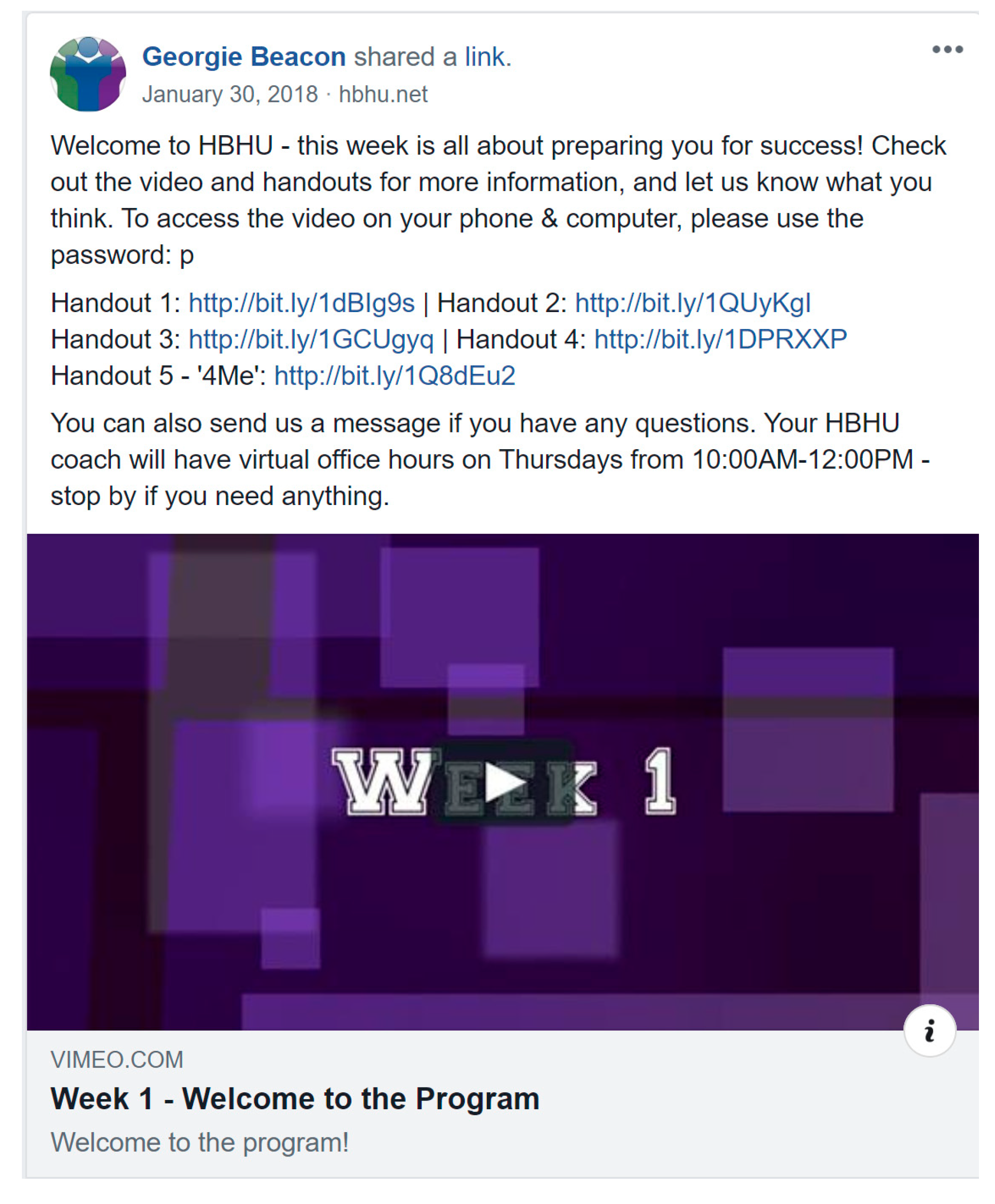

3.1. Facebook Post Overview

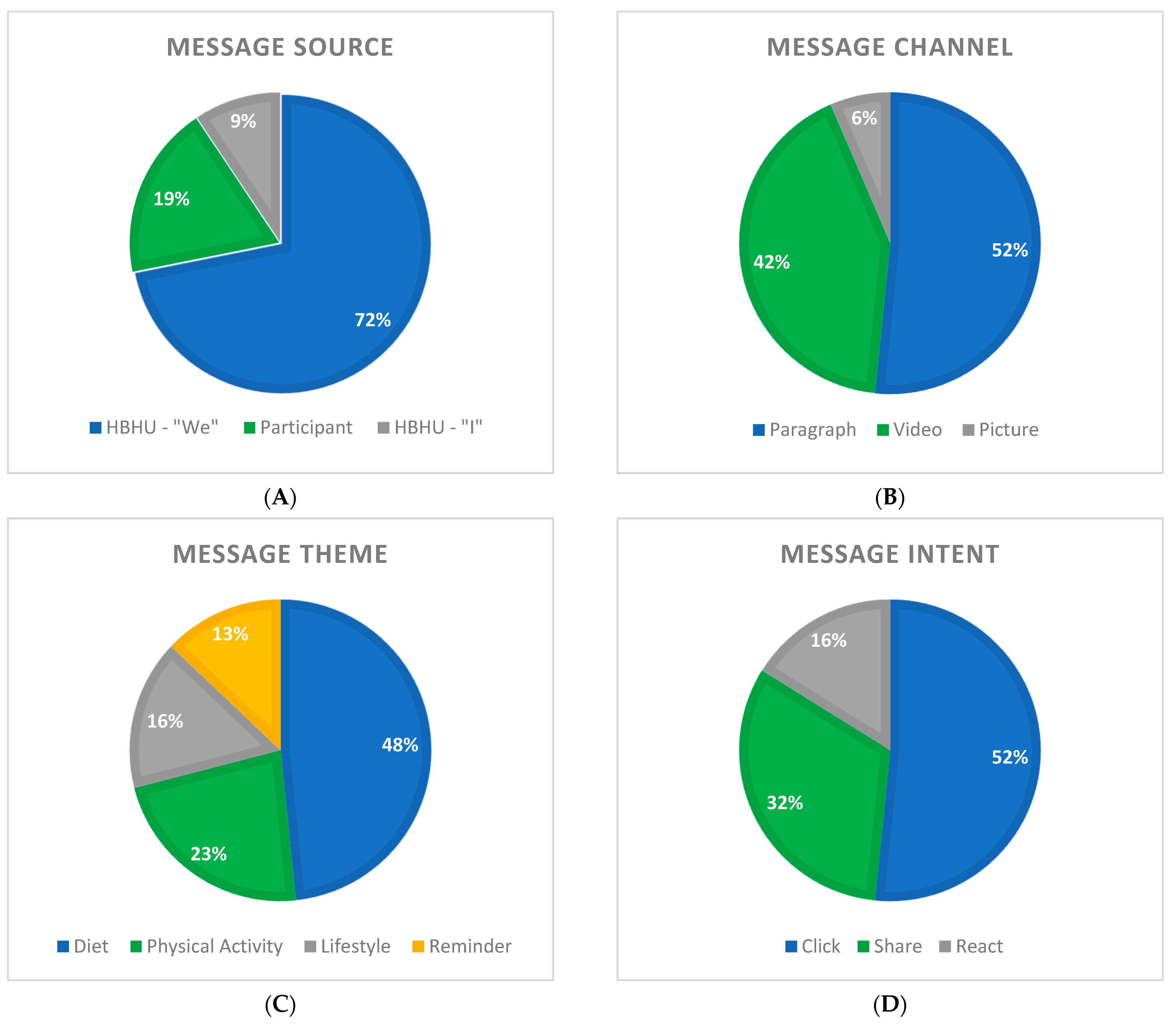

3.2. Facebook Post Characteristics by Source

3.3. Facebook Post Characteristics by Channel

3.4. Facebook Post Characteristics by Theme

3.5. Facebook Post Characteristics by Intent

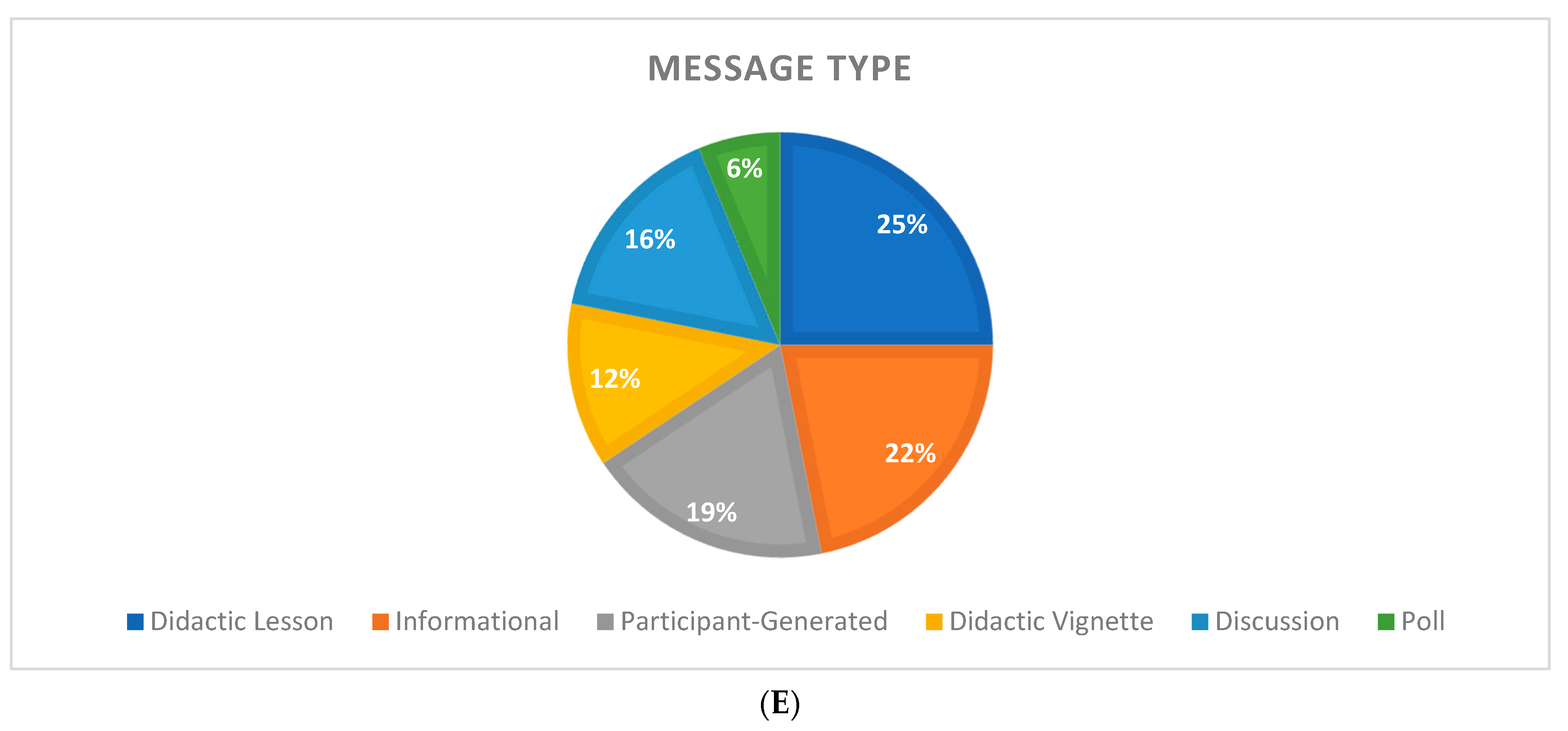

3.6. Facebook Post Characteristics by Message Type

3.7. Facebook Post Characteristics by Receiver

3.8. Facebook Posts Characteristics by Effect

3.9. Participant Demographics and Message Effects

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietz, W.H. Obesity and Excessive Weight Gain in Young Adults: New Targets for Prevention. JAMA 2017, 318, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, C.M.; Carrol, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018; NCHS Data Brief, no 360; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Yuan, C.; Liang, M.H.; Grodstein, F.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Associations of Weight Gain From Early to Middle Adulthood With Major Health Outcomes Later in Life. JAMA 2017, 318, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PEW. Mobile Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Perrin, A.; Atske, S. About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Say They Are ‘Almost Constantly’ Online. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/26/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-say-they-are-almost-constantly-online/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Auxier, B.; Anderson, M. Social Media Use in 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Lozano-Chacon, B.; Suarez-Lledo, V.; Alvarez-Galvez, J. Use and Effectiveness of Social-Media-Delivered Weight Loss Interventions among Teenagers and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkovic, J.; Duench, S.; Trawin, J.; Dewidar, O.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Simeon, R.; DesMeules, M.; Gagnon, D.; Hatcher Roberts, J.; Hossain, A.; et al. Behavioural interventions delivered through interactive social media for health behaviour change, health outcomes, and health equity in the adult population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, CD012932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waring, M.E.; Jake-Schoffman, D.E.; Holovatska, M.M.; Mejia, C.; Williams, J.C.; Pagoto, S.L. Social Media and Obesity in Adults: A Review of Recent Research and Future Directions. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, S.B.; Davidson, C.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M. Varying social media post types differentially impacts engagement in a behavioral weight loss intervention. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014, 4, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unick, J.L.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Demos, K.E.; Dorfman, L. Initial Weight Loss Response as an Indicator for Providing Early Rescue Efforts to Improve Long-term Treatment Outcomes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2017, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, W.J. Input and Output Variables Currently Promising for Constructing Persuasive Communications. In Public Communication Campaigns; Rice, R.E., Atkin, C.K., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. McGuire’s Classic Input-Output Framework for Constructing Persuasive Messages. In Public Communication Campaigns, 4th ed.; Rice, R.E., Atkin, C.K., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Holt, C.L.; Kreuter, M.W.; Clark, E.M.; Scharff, D. Understanding the Effects of Printed Health Education Materials: Which Features Lead to Which Outcomes? J. Health Commun. 2001, 6, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M.; Bell, T.; Kelley, D.; Barker, J.; Yzer, M. Perceived Message Effectiveness Measures in Tobacco Education Campaigns: A Systematic Review. Commun. Methods Meas. 2018, 12, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Chou, D. An Analysis of Tzu Chi’s Public Communication Campaign on Body Donation. China Media Res. 2008, 4, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano, M.A.; Whiteley, J.A.; Mavredes, M.N.; Faro, J.; DiPietro, L.; Hayman, L.L.; Neighbors, C.J.; Simmens, S. Using social media to deliver weight loss programming to young adults: Design and rationale for the Healthy Body Healthy U (HBHU) trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.A.; Whiteley, J.A.; Mavredes, M.; Tjaden, A.H.; Simmens, S.; Hayman, L.L.; Faro, J.; Winston, G.; Malin, S.; DiPietro, L. Effect of tailoring on weight loss among young adults receiving digital interventions: An 18 month randomized controlled trial. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The diabetes prevention program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 2165–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Online Advertising Guide [TOAG]. (n.d.). Facebook Engagement Rate Calculator. Available online: https://theonlineadvertisingguide.com/ad-calculators/facebook-engagement-rate-calculator/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- York, A. The 6 Fundamental Facebook Best Practices. Available online: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/facebook-best-practices/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Northcott, C.; Curtis, R.; Bogomolova, S.; Olds, T.; Vandelanotte, C.; Plotnikoff, R.; Maher, C. Should Facebook advertisements promoting a physical activity smartphone app be image or video-based, and should they promote benefits of being active or the app attributes? Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2136–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosseri, A. Bringing People Closer Together. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2018/01/news-feed-fyi-bringing-people-closer-together/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. The Psychology of Fake News. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obadă, D.R.; Dabija, D.C. “In Flow”! Why Do Users Share Fake News about Environmentally Friendly Brands on Social Media? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Input Factor | Definition | Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Who is delivering the message? | Facebook posts in cohort groups could come from one of two sources: the HBHU study, or participants. HBHU posts were divided in two based on if the post language used “we” or “I” as the speaker. |

| Message | What form does the message take? | HBHU’s Facebook posts: “Didactic Lesson”; “Didactic Vignette”; “Discussion”; “Poll”; “Participant-Generated”. |

| Channel | How is the message delivered? | Designates the post’s communication medium: paragraph (written text), picture, or video |

| Theme | What is the theme of the message? | This is an additional variable intended to categorize the various HBHU posts. There are three major themes: physical activity, diet, and lifestyle. |

| Intent | What action does the message call for? | This represents the goal of the post: for click-throughs (e.g., to click on a video or handout), reactions (e.g., to participate in a poll), or comments (e.g., to share personal stories or information) |

| Receiver | Who is the message directed at? | To measure the audience of the message, this variable has been divided into three demographic variables (Age, Sex, BMI) in order to quantify the profile of an engaged receiver. |

| Effect | How successful is the message? | Facebook engagement scores will be used as a simplified output measure to determine degrees of success, or effectiveness (Total Engaged Users/Total Reach). |

| Week_Post | Source | Message | Channel | Theme | Intent | Receiver Age | Receiver Sex | Receiver BMI | Effect Score | Effect % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk1_Participant | Participant | Participant-Generated | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 20.00 | 2.00 | 30.60 | 1.00 | 100.00 |

| Wk3_Participant | Participant | Participant-Generated | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 24.00 | 1.67 | 32.76 | 1.00 | 100.00 |

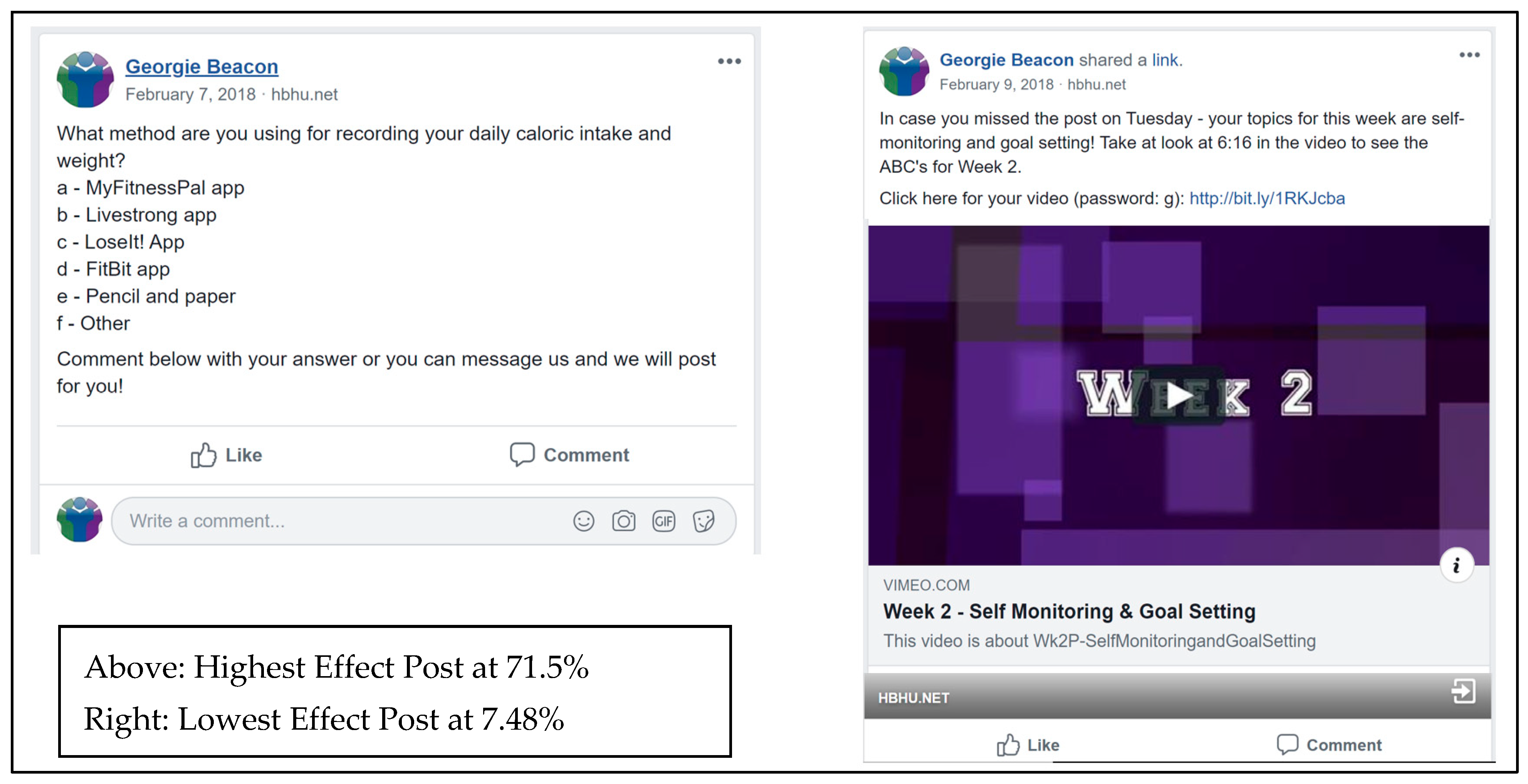

| Wk2_Wednesday | HBHU | Poll | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 23.79 | 1.86 | 31.53 | 0.71 | 71.50 |

| Wk1_Wednesday | HBHU | Discussion | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 24.64 | 1.90 | 32.36 | 0.35 | 35.29 |

| Wk4_Wednesday | HBHU | Poll | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 24.40 | 1.84 | 31.88 | 0.34 | 33.53 |

| Wk1_Participant2 | Participant | Participant-Generated | Picture | Physical Activity | Click | 26.50 | 2.00 | 32.16 | 0.33 | 33.33 |

| Wk2_WrapUp | Georgie | Discussion | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 23.66 | 1.97 | 31.91 | 0.29 | 28.79 |

| Wk3_Wednesday | HBHU | Discussion | Paragraph | Physical Activity | Share | 24.42 | 1.91 | 31.56 | 0.28 | 27.56 |

| Wk1_Tuesday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Lifestyle | Click | 24.61 | 1.87 | 34.07 | 0.22 | 22.16 |

| Wk1_Welcome | HBHU | Informational | Video | Lifestyle | Click | 24.63 | 1.94 | 33.25 | 0.20 | 20.47 |

| Wk1_Thursday | HBHU | Didactic Vignette | Video | Lifestyle | Click | 24.44 | 1.88 | 31.77 | 0.20 | 20.24 |

| Wk3_environment | HBHU | Informational | Picture | Diet | Click | 23.70 | 1.85 | 30.85 | 0.20 | 20.00 |

| Wk1_WrapUp | Georgie | Discussion | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 23.30 | 1.91 | 32.93 | 0.19 | 18.70 |

| Wk3_Thursday | HBHU | Didactic Vignette | Video | Physical Activity | Click | 23.25 | 1.88 | 31.13 | 0.17 | 16.55 |

| Wk2_Monday | HBHU | Informational | Paragraph | Reminder | React | 24.45 | 1.82 | 32.57 | 0.16 | 15.60 |

| Wk2_Tuesday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Lifestyle | Click | 22.82 | 1.77 | 32.47 | 0.15 | 14.77 |

| Wk2_Thursday | HBHU | Didactic Vignette | Video | Diet | Click | 23.16 | 1.68 | 30.80 | 0.14 | 14.49 |

| Wk3_Tuesday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Physical Activity | Click | 24.80 | 1.85 | 31.42 | 0.14 | 13.79 |

| Wk4_WrapUp | HBHU | Informational | Paragraph | Diet | React | 24.83 | 1.92 | 30.40 | 0.12 | 12.37 |

| Wk3_Friday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Physical Activity | Click | 25.07 | 1.79 | 32.54 | 0.12 | 12.17 |

| Wk4_Thursday | HBHU | Didactic Vignette | Video | Diet | Click | 24.50 | 1.88 | 31.54 | 0.12 | 11.76 |

| Wk4_Monday | HBHU | Informational | Paragraph | Reminder | React | 24.60 | 1.80 | 32.48 | 0.12 | 11.63 |

| Wk3_Monday | HBHU | Informational | Paragraph | Reminder | React | 23.65 | 1.82 | 31.26 | 0.12 | 11.56 |

| Wk4_Tuesday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Diet | Click | 23.80 | 1.87 | 31.41 | 0.11 | 11.28 |

| Wk1_Monday | HBHU | Informational | Paragraph | Reminder | React | 24.33 | 1.72 | 34.11 | 0.11 | 11.11 |

| Wk3_WrapUp | Georgie | Discussion | Paragraph | Physical Activity | Click | 25.60 | 2.00 | 30.28 | 0.11 | 10.71 |

| Wk1_Friday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Lifestyle | Click | 25.78 | 2.00 | 29.18 | 0.10 | 9.52 |

| Wk4_Friday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Diet | Click | 23.36 | 1.73 | 31.44 | 0.08 | 8.27 |

| Wk2_Friday | HBHU | Didactic Lesson | Video | Diet | Click | 21.73 | 1.73 | 30.04 | 0.07 | 7.48 |

| Wk2_Participant | Participant | Participant-Generated | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 29.00 | 2.00 | 29.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Wk4_Participant | Participant | Participant-Generated | Paragraph | Physical Activity | Share | 27.00 | 2.00 | 27.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Wk3_Participant2 | Participant | Participant-Generated | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Highest Effect Posts | Source | Message | Channel | Theme | Intent | Age | Sex | BMI | Effect % |

| In general | HBHU-we | Discussion OR Poll | Paragraph | Diet | Share | 24.58 | 1.91 | 32.34 | 34.08 |

| Lowest Effect Posts | Source | Message | Channel | Theme | Intent | Age | Sex | BMI | Effect % |

| In general | HBHU-we | Didactic Lesson OR Informational | Video | Diet OR Reminder | Click | 24.15 | 1.84 | 31.31 | 10.37 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnold, J.; Bailey, C.P.; Evans, W.D.; Napolitano, M.A. Application of McGuire’s Model to Weight Management Messages: Measuring Persuasion of Facebook Posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U Trial for Young Adults Attending University in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114275

Arnold J, Bailey CP, Evans WD, Napolitano MA. Application of McGuire’s Model to Weight Management Messages: Measuring Persuasion of Facebook Posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U Trial for Young Adults Attending University in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114275

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnold, Jeanie, Caitlin P. Bailey, W. Douglas Evans, and Melissa A. Napolitano. 2022. "Application of McGuire’s Model to Weight Management Messages: Measuring Persuasion of Facebook Posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U Trial for Young Adults Attending University in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114275

APA StyleArnold, J., Bailey, C. P., Evans, W. D., & Napolitano, M. A. (2022). Application of McGuire’s Model to Weight Management Messages: Measuring Persuasion of Facebook Posts in the Healthy Body, Healthy U Trial for Young Adults Attending University in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114275