Relative Deprivation Leads to the Endorsement of “Anti-Chicken Soup” in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Income Inequality and Relative Deprivation

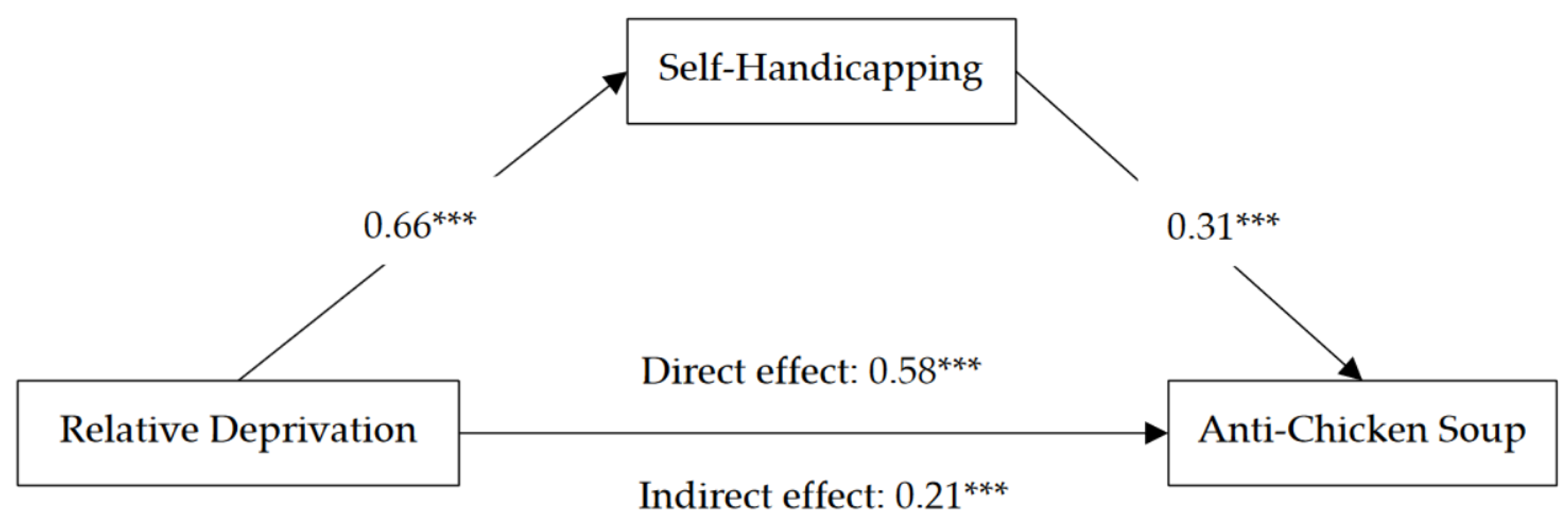

1.2. Relative Deprivation, Endorsement of Anti-Chicken Soup, and Self-Handicapping

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.2. Measures

2.1.3. Missing Values Analysis

2.2. Results

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

3.1.2. Measures

3.2. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shihan, J. Chicken Soup for the Soul from the perspective of social psychology. Teens China 2016, 15, 247–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ziming, D. Emotional Release and Technological Birth: Cultural Interpretation of “Loss” in the Context of New Media; Press Circles: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z. Guang Ming Ri Bao: Yin Dao Nian Qing Ren Yuan Li Sang Wen Hua Qin Shi [Guangming Daily: Guide the Youth to Stay Away from the Erosion of Sang Culture]. Available online: http://www.people.com.cn/ (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Zhong, Z. Using the principle of reading therapy to explain the effect of “anti-chicken soup”. Great East. J. 2016, 5, 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.; Zhijie, W.; Peijing, Z. Analysis and Prevention of the phenomenon of “Sang culture”. Beijing Educ. 2017, 11, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaojing, C. Analysis and Counertmeasures of the Popular Online Phenomena of “Depression Culture” among Contemporary Youth. J. Shanxi Youth Voc. Coll. 2018, 31, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Pippin, G.M.; Bialosiewicz, S. Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. Wage Labour and Capital; Rhenish Newspaper: Rhineland, Germany, 1847. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, O.P. Who feels it? Income inequality, relative deprivation, and financial satisfaction in US states, 1973–2012. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2019, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, A.; Borland, R. Residual outcome expectations and relapse in ex-smokers. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.W. General strain, street youth and crime: A test of Agnew’s revised theory. Criminology 2004, 42, 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, M.J.; Ellard, J.H.; Will Shead, N.; Hodgins, D.C. Gambling as a search for justice: Examining the role of personal relative deprivation in gambling urges and gambling behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1514–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Oliver, M.B. Cultivation effects on quality of life indicators: Exploring the effects of American television consumption on feelings of relative deprivation in South Korea and India. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2008, 52, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.F.R.; Yang, J.H. Exploring Hikikomori: A Mixed Methods Qualitative Research; The University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V. Social withdrawal as invisible youth disengagement: Government inaction and NGO responses in Hong Kong. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, T.; Norasakkunkit, V.; Uchida, Y. Unable to conform, unwilling to rebel? Youth, culture, and motivation in globalizing Japan. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M.; Wong, P.W. Youth social withdrawal behavior (hikikomori): A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouyan, D. The Phenomenon of “Sang culture” and The Perspective of Youth Social Mentality. China Youth Study 2017, 11, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk, B.P.; Janssen, P.P.M. Relative deprivation, career issues, and mental health among men in midlife. J. Vocat. Behav. 1992, 40, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.; Adler, N.E.; Kawachi, I.; Frazier, A.L.; Huang, B.; Colditz, G.A. Adolescents’ perspectives of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics 2001, 108, E31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshai, S.; Mishra, S.; Meadows, T.J.S.; Parmar, P.; Huang, V. Minding the gap: Subjective relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 173, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.S. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Some benefits of rationalization. Philos. Explor. 2017, 20, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiting, H.; Wei, S. The Self-Handicapping Strategy: It’s Paradigm and It’s Correlational Variables. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Berglas, S.; Jones, E.E. Drug choice as a self-handicapping strategy in response to noncontingent success. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 36, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Smith, T.W. Symptoms as self-handicapping strategies: The virtues of old wine in a new bottle. In Integrations of Clinical and Social Psychology; Weary, G., Mirels, H.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 104–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J. Determinants of reduction in intended effort as a strategy for coping with anticipated failure. J. Res. Personal. 1983, 17, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodewalt, F. Self-handicappers: Individual differences in the preference for anticipatory, self-protective acts. In Self-Handicapping: The Paradox That Isn’t; Higgins, R.L., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 69–106. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.W.; Snyder, C.R.; Perkins, S.C. The self-serving function of hypochondriacal complaints: Physical symptoms as self-handicapping strategies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Smith, T.W.; Augelli, R.W.; Ingram, R.E. On the self-serving function of social anxiety: Shyness as a self-handicapping strategy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strube, M.J. An analysis of the self-handicapping scale. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 7, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M. Esteem protection or enhancement? Self-handicapping motives and attributions differ by trait self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browman, A.S.; Destin, M.; Miele, D.B. Perception of economic inequality weakens Americans’ beliefs in both upward and downward socioeconomic mobility. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 25, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.F.; Liu, J.R. Cognitive schema and information reception. Libr. Dev. 1999, 3, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, H.; Liang, Z.; Wang, X. Improvement of Social Support for Children with Relative Deprivation by Resilience Based on the Effect of Elastic Psychological Training. Adv. Psychol. 2016, 6, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, M.J.; Shead, N.W.; Olson, J.M. Personal relative deprivation, delay discounting, and gambling. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.B.; Einav, M.; Margalit, M. Does family cohesion predict children’s effort? The mediating roles of sense of coherence, hope, and loneliness. J. Psychol. 2018, 152, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugini, M.; Gallucci, M.; Costantini, G. A Practical Primer to Power Analysis for Simple Experimental Designs. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 31, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.Y.; Lim, E.X.; Forde, C.G.; Cheon, B.K. Personal relative deprivation increases self-selected portion sizes and food intake. Appetite 2018, 121, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.E.; Rhodewalt, F. The Self-Handicapping Scale; Department of Psychology, Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsa, A.I.; French, M.T.; Regan, T.L. Relative Deprivation and Risky Behaviors. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 49, 446–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, D. Wealth: Having It All and Wanting More; Oxfam International: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver, P.; Schwartz, J.; Kirson, D.; O’Connor, C. Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 1061–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirlott, A.G.; Mackinnon, D. Design approaches to experimental mediation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 66, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | - | - | - | |||||

| 2 Age | 27.61 | 6.30 | 0.159 * | - | ||||

| 3 Income | 1.76 | 0.91 | 0.257 *** | 0.426 *** | - | |||

| 4 Education | 3.04 | 0.59 | −0.074 | −0.204 ** | −0.004 | - | ||

| 5 RD | 2.99 | 0.72 | 0.014 | −0.314 *** | −0.147 * | −0.077 | - | |

| 6 ACS Endorsement | 2.95 | 0.72 | 0.051 | −0.039 | −0.070 | 0.026 | 0.373 *** | - |

| Variables | β | B (SE) | t | p | 95% CI of B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.12 (0.108) | 1.12 | 0.262 | −0.09 | 0.34 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 (0.009) | −0.11 | 0.910 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Income | −0.09 | −0.07 (0.059) | −1.16 | 0.248 | −0.19 | 0.05 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.04 (0.083) | 0.44 | 0.659 | −0.13 | 0.20 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.81 | 0.421 | −0.12 | 0.28 |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.85 | 0.066 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Income | −0.08 | −0.06 (0.06) | −1.15 | 0.250 | −0.17 | 0.05 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.11 (0.08) | 1.40 | 0.162 | −0.04 | 0.26 |

| RD | 0.41 | 0.41 (0.06) | 6.34 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.54 |

| R2 | 0.16 | |||||

| ΔR2 | 0.15 *** | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, S. Relative Deprivation Leads to the Endorsement of “Anti-Chicken Soup” in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114210

Zhang X, Wang T, Liu Z, Sun X, Yang S. Relative Deprivation Leads to the Endorsement of “Anti-Chicken Soup” in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114210

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaomeng, Tianxin Wang, Zhenzhen Liu, Xiaomin Sun, and Shuting Yang. 2022. "Relative Deprivation Leads to the Endorsement of “Anti-Chicken Soup” in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114210

APA StyleZhang, X., Wang, T., Liu, Z., Sun, X., & Yang, S. (2022). Relative Deprivation Leads to the Endorsement of “Anti-Chicken Soup” in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114210