Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

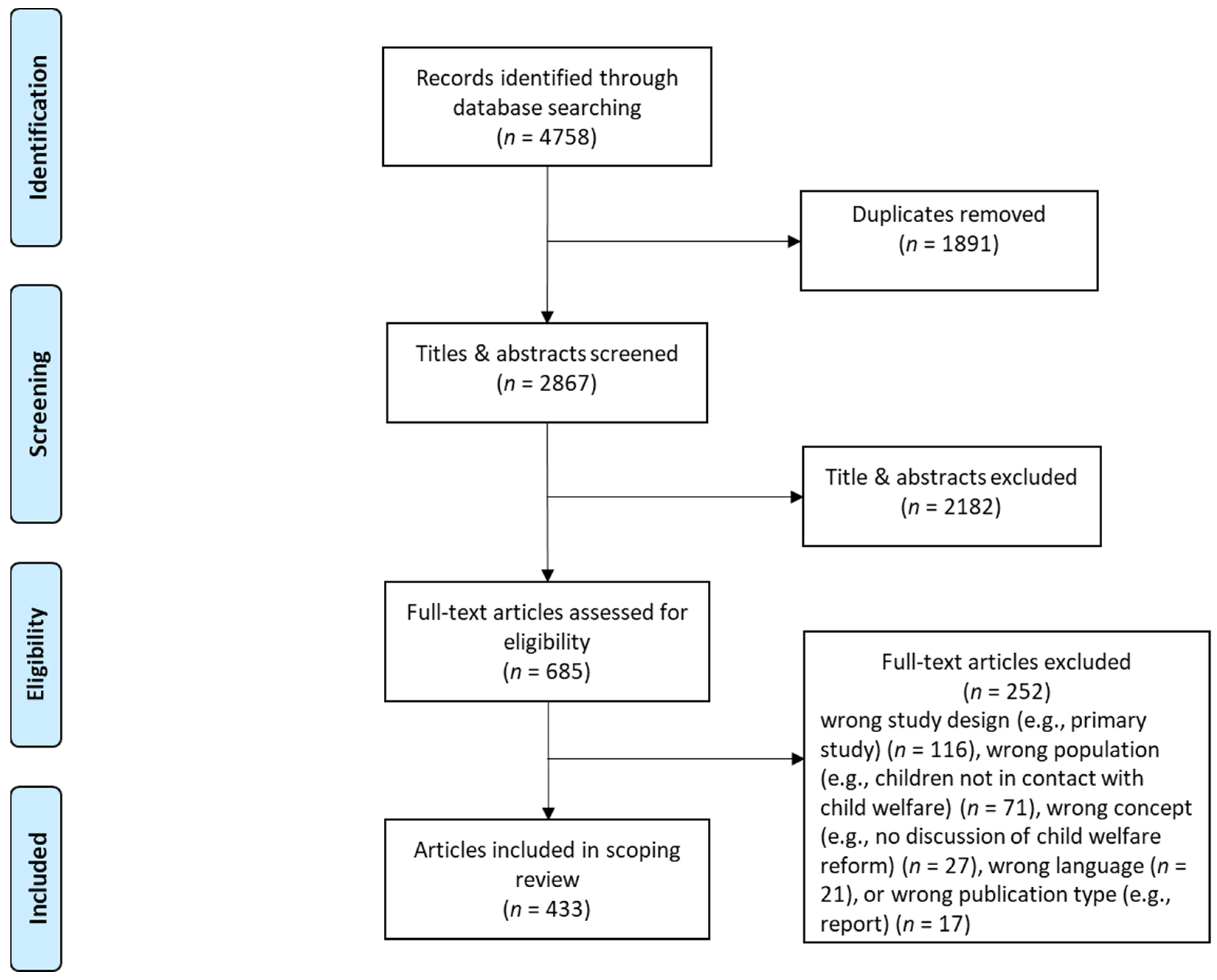

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Systematic Search

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Types of Reviews

3.2. Population Focus

3.3. Thematic Focus

3.3.1. Societal-Level Thematic Focus

3.3.2. Community-Level Thematic Focus

3.3.3. Institutional-Level Thematic Focus

3.3.4. Individual-Level Thematic Focus

3.4. Improvements across Socioecological Levels

3.4.1. Societal-Level Suggestions for Improvements

3.4.2. Community-Level Suggestions for Improvements

3.4.3. Institutional-Level Suggestions for Improvements

3.4.4. Relationship-Level Suggestions for Improvements

3.4.5. Individual-Level Suggestions for Improvements

4. Discussion

- over-inclusion (for example, unnecessary child protection reports);

- under-inclusion (such as, inadequate support and protection for vulnerable children, particularly in response to sexual abuse and exploitation);

- service capacity (for example, severe funding shortages; gaps in services);

- service delivery (such as, adversarial relationships with parents; discrimination towards low-income families); and

- service orientation (for example, residual child welfare, or only providing support as a last resort when all other avenues fail; crisis intervention orientated).

4.1. Societal-Level Reform

4.2. Community-Level Reform

4.3. Institutional-Level Reform

4.4. Relationship-Level Reform

4.5. Individual-Level Reform

4.6. Limitations, Future Research, and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McTavish, J.R.; MacGregor, J.C.D.; Wathen, C.N.; MacMillan, H.L. Children’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence: An Overview. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Development of Guidelines for the Health Sector Response to Child Maltreatment. Available online: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/child/child_maltreatment_guidelines/en/ (accessed on 26 June 2017).

- McCrory, E.; De Brito, S.A.; Viding, E. The Link between Child Abuse and Psychopathology: A Review of Neurobiological and Genetic Research. J. R. Soc. Med. 2012, 105, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Parker, K.J. Psychological Stress in Childhood and Susceptibility to the Chronic Diseases of Aging: Moving toward a Model of Behavioral and Biological Mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 959–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, A.M.; Maguire, S.A.; Mann, M.K.; Lumb, R.C.; Tempest, V.; Gracias, S.; Kemp, A.M. Emotional, Behavioral, and Developmental Features Indicative of Neglect or Emotional Abuse in Preschool Children: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, R.E.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The Long-Term Health Consequences of Child Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse, and Neglect: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenema, T.G.; Thornton, C.P.; Corley, A. The Public Health Crisis of Child Sexual Abuse in Low and Middle Income Countries: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 864–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.; Kemp, A.; Thoburn, J.; Sidebotham, P.; Radford, L.; Glaser, D.; MacMillan, H.L. Recognising and Responding to Child Maltreatment. Lancet 2009, 373, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). Available online: http://cwrp.ca/faqs (accessed on 5 October 2015).

- Rouland, B.; Vaithianathan, R. Cumulative Prevalence of Maltreatment among New Zealand Children, 1998–2015. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Wildeman, C.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Drake, B. Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment among US Children. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.; Lefebvre, R.; Trocmé, N.; Richard, K.; Hélie, S.; Montgomery, M.; Bennett, M.; Joh-Carnella, N.; Saint-Girons, M.; Filippelli, J.; et al. Denouncing the Continued Overrepresentation of First Nations Children in Canadian Child Welfare: Findings from the First Nations/Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2019; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lonne, B.; Higgins, D.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Scott, D. Reconstructing the Workforce within Public Health Protective Systems: Improving Resilience, Retention, Service Responsiveness and Outcomes. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnerljung, B.; Sundell, K.; Löfholm, C.A.; Humlesjö, E. Former Stockholm Child Protection Cases as Young Adults: Do Outcomes Differ between Those That Received Services and Those That Did Not? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, O.G.; Hindley, N.; Jones, D.P. Risk Factors for Child Maltreatment Recurrence: An Updated Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Law 2014, 55, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.M.; Bruch, S.K.; Johnson, E.I.; James, S.; Rubin, D. Estimating the “Impact” of out-of-Home Placement on Child Well-Being: Approaching the Problem of Selection Bias. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1856–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Higgins, A.; Sebba, J.; Gardner, F. What Are the Factors Associated with Educational Achievement for Children in Kinship or Foster Care: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypen, L.; Vanderfaeillie, J.; De Maeyer, S.; Belenger, L.; Van Holen, F. Outcomes of Children Who Grew up in Foster Care: Systematic-Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 76, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chng, G.S.; Chu, C.M. Comparing Long-Term Placement Outcomes of Residential and Family Foster Care: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijbosch, E.L.L.; Huijs, J.A.M.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Wissink, I.B.; van der Helm, G.H.P.; de Swart, J.J.W.; van der Veen, Z. The Outcome of Institutional Youth Care Compared to Non-Institutional Youth Care for Children of Primary School Age and Early Adolescence: A Multi-Level Meta-Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 58, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bright, C.L. Children’s Mental Health and Its Predictors in Kinship and Non-Kinship Foster Care: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 89, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvaso, C.G.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Day, A. The Child Protection and Juvenile Justice Nexus in Australia: A Longitudinal Examination of the Relationship between Maltreatment and Offending. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 64, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.A. Child Welfare Reform and the Political Process. Soc. Serv. Rev. 1986, 60, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E. The Costs of Child Protection in the Context of Welfare Reform. Future Child. 1998, 8, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Callahan, M.; Walmsley, C. Rethinking Child Welfare Reform in British Columbia, 1900–60. In People, Politics, and Child Welfare in British Columbia; Foster, L.T., Wharf, B., Eds.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; ISBN 978-0-7748-4097-2. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, K.J.; Parada, H. Child Welfare Reform: Protecting Children or Policing the Poor. J.L. Soc. Pol’y 2004, 19, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Universal Violence and Child Maltreatment Prevention Programs for Parents: A Systematic Review. Psychosoc. Interv. 2016, 25, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyana Amin, N.A.; Tam, W.W.S.; Shorey, S. Enhancing First-Time Parents’ Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Universal Parent Education Interventions’ Efficacy. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coore Desai, C.; Reece, J.-A.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S. The Prevention of Violence in Childhood through Parenting Programmes: A Global Review. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, M.S.S.; Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Universal Intervention to Strengthen Parenting and Prevent Child Maltreatment: Updated Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 23, 15248380211013132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikton, C.; Butchart, A. Child Maltreatment Prevention: A Systematic Review of Reviews. World Health Organ. Bull. 2009, 87, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chan, K.L. Effects of Parenting Programs on Child Maltreatment Prevention: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015, 17, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, S.; Alink, L.R.; Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; IJzendoorn, M.H. van A Gloomy Picture: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Reveals Disappointing Effectiveness of Programs Aiming at Preventing Child Maltreatment. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Sara Opie, R.; Dalziel, K. Theory! The Missing Link in Understanding the Performance of Neonate/Infant Home-Visiting Programs to Prevent Child Maltreatment: A Systematic Review. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 47–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M.K.; Seal, D.W.; Taylor, C.A. A Systematic Review of Universal Campaigns Targeting Child Physical Abuse Prevention. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 388–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Zwi, K.; Woolfenden, S.; Shlonsky, A. School-Based Education Programmes for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse: A Systematic Review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 16, CD004380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Put, C.E.; Assink, M.; Gubbels, J.; Boekhout van Solinge, N.F. Identifying Effective Components of Child Maltreatment Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudt, H.; Mossel, C.; Scott, S. Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Interprofessional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, R. World Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8039-5540-0. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.A.; Fauser, B.C.J.M. Balancing the Strengths of Systematic and Narrative Reviews. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Ganeshkumar, P. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2013, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Antony, J.; Zarin, W.; Strifler, L.; Ghassemi, M.; Ivory, J.; Perrier, L.; Hutton, B.; Moher, D.; Straus, S.E. A Scoping Review of Rapid Review Methods. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachal, J.; Revah-Levy, A.; Orri, M.; Moro, M.R. Metasynthesis: An Original Method to Synthesize Qualitative Literature in Psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skouteris, H.; McCabe, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Henwood, A.; Limbrick, S.; Miller, R. Obesity in Children in Out-of-Home Care: A Review of the Literature. Aust. Soc. Work 2011, 64, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Morris, T.L. Psychological Adjustment of Children in Foster Care: Review and Implications for Best Practice. J. Public Child Welf. 2012, 6, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.; Tomlinson, C.; Beck, C.; Bowen, A. The Revolving Door of Families in the Child Welfare System: Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Families Returning. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Algood, C.L.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Lee, S.A.-P. An Ecological Understanding of Kinship Foster Care in the United States. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winokur, M.A.; Holtan, A.; Batchelder, K.E. Systematic Review of Kinship Care Effects on Safety, Permanency, and Well-Being Outcomes. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2018, 28, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. Family Drug Courts in Child Welfare. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2012, 29, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang-Yi, C.D.; Adams, D.R. Youth with Behavioral Health Disorders Aging out of Foster Care: A Systematic Review and Implications for Policy, Research, and Practice. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 44, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A.L.; Palmer, L.; Ahn, E. Pregnant and Parenting Youth in Care and Their Children: A Literature Review. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2019, 36, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, D.V.; Shaw, T.V.; Barth, R.P.; Bright, C.L. Pregnancy and Parenting among Youth in Foster Care: A Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, V.R.; Brandon-Friedman, R.A.; Ely, G.E. Sexual Health Behaviors and Outcomes among Current and Former Foster Youth: A Review of the Literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 64, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, A.M.; Gramm, H.B.; Paaske, I.; Kleiven, P.G.; Christiansen, Ø.; Skaale Havnen, K.J. Suicidality among Children and Youth in Nordic Child Welfare Services: A Systematic Review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2021, 26, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwool, N. Transition from Care: Are We Continuing to Set Care Leavers up to Fail in New Zealand? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R.J. The Potential Contribution of Mentor Programs to Relational Permanency for Youth Aging out of Foster Care. Child Welf. 2011, 90, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, S.R.; Abrams, L.S. Housing and Social Support for Youth Aging out of Foster Care: State of the Research Literature and Directions for Future Inquiry. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2015, 32, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häggman-Laitila, A.; Salokekkilä, P.; Karki, S. Transition to Adult Life of Young People Leaving Foster Care: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 95, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, A.T.; Mann-Feder, V.; Oterholm, I.; Refaeli, T. Supporting Transitions to Adulthood for Youth Leaving Care: Consensus Based Principles. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargeman, M.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Trauma-Informed Care as a Rights-Based “Standard of Care”: A Critical Review. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiles, D.; Moss, D.; Wright, J.; Dallos, R. Young People’s Experience of Social Support during the Process of Leaving Care: A Review of the Literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Collins, C.; Fischer, R.; Groza, V.; Yang, L. Exploring the Association between Housing Insecurity and Child Welfare Involvement: A Systematic Review. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2020, 39, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, H.E.; McBeath, B. Infusing Culture into Practice: Developing and Implementing Evidence-Based Mental Health Services for African American Foster Youth. Child Welf. 2010, 89, 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, A.; Gamboni, C.; Johnson, V.; Wojciak, A.S.; Ronnenberg, M. Has the US Child Welfare System Become an Informal Income Maintenance Programme? A Literature Review. Child Abus. Rev. 2020, 29, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, D.M.; Ray-Novak, M.; Gillani, B.; Peterson, E. Sexual and Gender Minority Youth in Foster Care: An Evidence-Based Theoretical Conceptual Model of Disproportionality and Pychological Comorbidities. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 23, 15248380211013128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberstein, K. Parenting in Families of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Review with Implications for Child Welfare Practice. Fam. Court Rev. 2016, 54, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.P.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Greeson, J.K.P.; Drake, B.; Berrick, J.D.; Garcia, A.R.; Shaw, T.V.; Gyourko, J.R. Outcomes Following Child Welfare Services: What Are They and Do They Differ for Black Children? J. Public Child Welf. 2020, 14, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbs, T.D. Leading with Racial Equity: Promoting Black Family Resilience in Early Childhood. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R. African American Disproportionality and Disparity in Child Welfare: Toward a Comprehensive Conceptual Framework. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 37, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; McIntee, S.-E.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Noorishad, P.-G. Overrepresentation of Black Children in the Child Welfare System: A Systematic Review to Understand and Better Act. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettlaff, A.J.; Boyd, R. Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them? Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2020, 692, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatwiri, K.; McPherson, L.; Parmenter, N.; Cameron, N.; Rotumah, D. Indigenous Children and Young People in Residential Care: A Systematic Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 22, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, W.; Waubanascum, C.; Glesener, D.; Marsalis, S. A Scoping Study of Indigenous Child Welfare: The Long Emergency and Preparations for the next Seven Generations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 93, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.C.; Varghese, R. Four Contexts of Institutional Oppression: Examining the Experiences of Blacks in Education, Criminal Justice and Child Welfare. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Gilbert, T.; Lee, S.J.; Staller, K.M. Reforming a System That Cannot Reform Itself: Child Welfare Reform by Class Action Lawsuits. Soc. Work 2019, 64, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J. The Intersection and Parallels of Aboriginal Peoples’ and Racialized Migrants’ Experiences of Colonialism and Child Welfare in Canada. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, M.; Linno, M.; Pael, J.; Lenk-Adusoo, M.; Timonen-Kallio, E. Mental Health Care Interventions in Child Welfare: Integrative Review of Evidence-Based Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, S.; Fortin, K.; Forkey, H. Medical Management and Trauma-Informed Care for Children in Foster Care. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2015, 45, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconnier, L.A.; Tomasello, N.M.; Doueck, H.J.; Wells, S.J.; Luckey, H.; Agathen, J.M. Indicators of Quality in Kinship Foster Care. Fam. Soc. 2010, 91, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, R.; Berger Cardoso, J. Child Human Trafficking Victims: Challenges for the Child Welfare System. Eval. Program Plan. 2010, 33, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeson, J.K.P.; Garcia, A.R.; Tan, F.; Chacon, A.; Ortiz, A.J. Interventions for Youth Aging out of Foster Care: A State of the Science Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isokuortti, N.; Aaltio, E.; Laajasalo, T.; Barlow, J. Effectiveness of Child Protection Practice Models: A Systematic Review. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 108, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.D. The Invisibility of Adolescent Sexual Development in Foster Care: Seriously Addressing Sexually Transmitted Infections and Access to Services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, R.R.; Henderson, C.M.; Boss, R.D. Medical Foster Care: What Happens When Children with Medical Complexity Cannot Be Cared for by Their Families? Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D.M.; Oliveros, A.; Hawes, S.W.; Iwamoto, D.K.; Rayford, B.S. Engaging Fathers in Child Protection Services: A Review of Factors and Strategies across Ecological Systems. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campie, P.E.; Pakstis, A.; Flynn, K.; McDermott, K. Developing a Coherent Approach to Youth Well-Being in the Fields of Child Welfare, Juvenile Justice, Education, and Health: A Systematic Literature Review. Fam. Soc. 2015, 96, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Wells, M. Behavioral and Substance Use Outcomes for Older Youth Living with a Parental Opioid Misuse: A Literature Review to Inform Child Welfare Practice and Policy. J. Public Child Welf. 2017, 11, 546–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.W.; Wakefield, S.M.; Morgan, W.; Aneja, A. Depression in Children and Adolescents Involved in the Child Welfare System. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 28, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E.R.; Concepcion-Zayas, M.T.; Zisman-Ilani, Y.; Bellonci, C. Patient-Centered Psychiatric Care for Youth in Foster Care: A Systematic and Critical Review. J. Public Child Welf. 2019, 13, 462–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.P.; Liggett-Creel, K. Common Components of Parenting Programs for Children Birth to Eight Years of Age Involved with Child Welfare Services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, M.; Cederblad, M.; Håkansson, K.; Jonsson, A.K.; Munthe, C.; Vinnerljung, B.; Wirtberg, I.; Östlund, P.; Sundell, K. Interventions in Foster Family Care: A Systematic Review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2020, 30, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, C.W.; Schwarz, D.F. Child Maltreatment and the Transition to Adult-Based Medical and Mental Health Care. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.L.; Wu, Q. Kinship Care and Service Utilization: A Review of Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 61, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M.T.; Bruns, E.J.; Lee, K.; Cox, S.; Coifman, J.; Mayworm, A.; Lyon, A.R. Rates of Mental Health Service Utilization by Children and Adolescents in Schools and Other Common Service Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2021, 48, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goemans, A.; van Geel, M.; van Beem, M.; Vedder, P. Developmental Outcomes of Foster Children: A Meta-Analytic Comparison with Children from the General Population and Children at Risk Who Remained at Home. Child Maltreat. 2016, 21, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, N.; MacEachron, A. Educational Policy and Foster Youths: The Risks of Change. Child. Sch. 2012, 34, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyon, Y. Reducing Racial Disparities and Disproportionalities in the Child Welfare System: Policy Perspectives about How to Serve the Best Interests of African American Youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.V.; Mountz, S.E.; Trant, J.; Quezada, N.M. A Black Feminist Approach for Caseworkers Intervening with Black Female Caregivers. J. Public Child Welf. 2020, 14, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.G.; Murphy, K.S.; Whitekiller, V.D.; Haggerty, K.P. Characteristics and Competencies of Successful Resource Parents Working in Indian Country: A Systematic Review of the Research. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, A.L.; Danes, S.M. Forgotten Children: A Critical Review of the Reunification of American Indian Children in the Child Welfare System. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 71, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, N.M.; Leake, R. Expressions of Culture in American Indian/Alaska Native Tribal Child Welfare Work: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Public Child Welf. 2016, 10, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, A.; Levy, M.; McClintock, K.; Tauroa, R. A Literature Review: Addressing Indigenous Parental Substance Use and Child Welfare in Aotearoa: A Whānau Ora Framework. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2015, 14, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A. Nurturing Identity among Indigenous Youth in Care. Child Youth Serv. 2020, 41, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahota, P.C. Kinship Care for Children Who Are American Indian/Alaska Native: State of the Evidence. Child Welf. 2019, 97, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, V.; Kozlowski, A. The Structure of Aboriginal Child Welfare in Canada. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.D.; Morrissey, M.W.; Beck, C.J. The Hispanic Experience of the Child Welfare System. Fam. Court Rev. 2019, 57, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degener, C.J.; van Bergen, D.D.; Grietens, H.W.E. The Ethnic Identity Complexity of Transculturally Placed Foster Youth in the Netherlands. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawrikar, P.; Katz, I.B. Recommendations for Improving Cultural Competency When Working with Ethnic Minority Families in Child Protection Systems in Australia. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2014, 31, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.; Austin, M.; Cormier, D. Early Detection of Prenatal Substance Exposure and the Role of Child Welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, M.; Radcliffe, P.; Marlow, S.; Boreham, M.; Gilchrist, G. Maternal Substance Use and Child Protection: A Rapid Evidence Assessment of Factors Associated with Loss of Child Care. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 70, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bortoli, L.; Coles, J.; Dolan, M. Linking Illicit Substance Misuse during Pregnancy and Child Abuse: What Is the Quality of the Evidence? Child Fam. Soc. Work 2014, 19, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doab, A.; Fowler, C.; Dawson, A. Factors That Influence Mother-Child Reunification for Mothers with a History of Substance Use: A Systematic Review of the Evidence to Inform Policy and Practice in Australia. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, R.A.; DePanfilis, D.; Woodruff, K. Parental Methamphetamine Use and Implications for Child Welfare Intervention: A Review of the Literature. J. Public Child Welf. 2010, 4, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.H. Family Drug Courts: Conceptual Frameworks, Empirical Evidence, and Implications for Social Work. Fam. Soc. 2015, 96, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.H.; Brook, J. Drug Testing in Child Welfare: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 104, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellus, L.; MacKinnon, K.; Gordon, C.; Shaw, L. Interventions and Programs That Support the Health and Development of Infants with Prenatal Substance Exposure in Foster Care: A Scoping Review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 1844–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.C.; Smith, B.D. Integrated Substance Abuse and Child Welfare Services for Women: A Progress Review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.L.; Harper, W.; Griffiths, A.; Joffrion, C. Family Reunification: A Systematic Review of Interventions Designed to Address Co-Occurring Issues of Child Maltreatment and Substance Use. J. Public Child Welf. 2017, 11, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, A.; Kaufman, J. Addressing Substance Abuse Treatment Needs of Parents Involved with the Child Welfare System. Child Welf. 2011, 90, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, T.; Bertrand, J.; Newburg-Rinn, S.; McCann, H.; Morehouse, E.; Ingoldsby, E. Children Prenatally Exposed to Alcohol and Other Drugs: What the Literature Tells Us about Child Welfare Information Sources, Policies, and Practices to Identify and Care for Children. J. Public Child Welf. 2022, 16, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, K. A Systematic Review of the Literature Regarding Family Context and Mental Health of Children from Rural Methamphetamine-Involved Families: Implications for Rural Child Welfare Practice. J. Public Child Welf. 2014, 8, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, L.; Schmidt, R.A.; Stinson, J.; Poole, N. Examining Barriers to Harm Reduction and Child Welfare Services for Pregnant Women and Mothers Who Use Substances Using a Stigma Action Framework. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Wu, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, M. The Impacts of Family Treatment Drug Court on Child Welfare Core Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 88, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, L. Could an Increased Focus on Identity Development in the Provision of Children’s Services Help Shape Positive Outcomes for Care Leavers?” A Literature Review. Child Care Pract. 2018, 24, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everson-Hock, E.S.; Jones, R.; Guillaume, L.; Clapton, J.; Duenas, A.; Goyder, E.; Chilcott, J.; Cooke, J.; Payne, N.; Sheppard, L.M.; et al. Supporting the Transition of Looked-after Young People to Independent Living: A Systematic Review of Interventions and Adult Outcomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 37, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häggman-Laitila, A.; Salokekkilä, P.; Karki, S. Integrative Review of the Evaluation of Additional Support Programs for Care Leavers Making the Transition to Adulthood. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 54, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havlicek, J. Lives in Motion: A Review of Former Foster Youth in the Context of Their Experiences in the Child Welfare System. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. Remaining in Foster Care after Age 18 and Youth Outcomes at the Transition to Adulthood: A Review. Fam. Soc. 2019, 100, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Morgan, W. Transitioning to Adulthood from Foster Care. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, S. Towards Parity in Protection: Barriers to Effective Child Protection and Welfare Assessment with Disabled Children in the Republic of Ireland. Child Care Pract. 2021, 27, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S. Social Work Intervention Pathways within Child Protection: Responding to the Needs of Disabled Children in Ireland. Practice 2021, 33, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L.; Kalichman, M.A. Council on Children with Disabilities; Council on Children with Disabilities Out-of-Home Placement for Children and Adolescents with Disabilities. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalker, K.; McArthur, K. Child Abuse, Child Protection and Disabled Children: A Review of Recent Research. Child Abus. Rev. 2012, 21, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, V.; Jones, C.; Stalker, K.; Stewart, A. Permanence for Disabled Children and Young People through Foster Care and Adoption: A Selective Review of International Literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 53, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziviani, J.; Feeney, R.; Cuskelly, M.; Meredith, P.; Hunt, K. Effectiveness of Support Services for Children and Young People with Challenging Behaviours Related to or Secondary to Disability, Who Are in out-of-Home Care: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, T.P.; Mathews, B.; Tonmyr, L.; Scott, D.; Ouimet, C. Child Welfare Policy and Practice on Children’s Exposure to Domestic Violence. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, I.N.; Pohle, C. Case Outcomes of Child Welfare-Involved Families Affected by Domestic Violence: A Review of the Literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1400–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, W.; Hester, M.; Broad, J.; Szilassy, E.; Feder, G.; Drinkwater, J.; Firth, A.; Stanley, N. Interventions to Improve the Response of Professionals to Children Exposed to Domestic Violence and Abuse: A Systematic Review. Child Abus. Rev. 2017, 26, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, H. Widening Inclusion for Gay Women Foster Carers—A Literature Review of the Sociological, Psychological and Economic Implications. Practice 2017, 29, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatwiri, K.; Cameron, N.; Mcpherson, L.; Parmenter, N. What Is Known about Child Sexual Exploitation in Residential Care in Australia? A Systematic Scoping Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C. ‘What Is the Impact of Birth Family Contact on Children in Adoption and Long-Term Foster Care?’ A Systematic Review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, C.; Damiani-Taraba, G. Always Together? Predictors and Outcomes of Sibling Co-Placement in Foster Care. Child Welf. 2018, 95, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hegar, R.L.; Scannapieco, M. Foster Care to Kinship Adoption: The Road Less Traveled. Adopt. Q. 2017, 20, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, A.L.; Foster, L.J.J.; Pecora, P.J.; Delaney, N.; Rodriguez, W. Reshaping Child Welfare’s Response to Trauma: Assessment, Evidence-Based Intervention, and New Research Perspectives. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2013, 23, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, S.; Creemers, H.E.; Asscher, J.J.; Deković, M.; Stams, G.J.J.M. The Effectiveness of Family Group Conferencing in Youth Care: A Meta-Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 62, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassarino-Perez, L.; Crous, G.; Goemans, A.; Montserrat, C.; Sarriera, J.C. From Care to Education and Employment: A Meta-Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 95, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finigan-Carr, N.M.; Murray, K.W.; O’Connor, J.M.; Rushovich, B.R.; Dixon, D.A.; Barth, R.P. Preventing Rapid Repeat Pregnancy and Promoting Positive Parenting among Young Mothers in Foster Care. Soc Work Public Health 2015, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.J. Mental Health Care of Families Affected by the Child Welfare System. Child Welf. 2014, 93, 7–57. [Google Scholar]

- Leve, L.D.; Harold, G.T.; Chamberlain, P.; Landsverk, J.A.; Fisher, P.A.; Vostanis, P. Practitioner Review: Children in Foster Care—Vulnerabilities and Evidence-Based Interventions That Promote Resilience Processes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, T.; Taplin, S.; McArthur, M.; Humphreys, C.; Kertesz, M. Interventions to Improve Supervised Contact Visits between Children in out of Home Care and Their Parents: A Systematic Review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; White, J.; Turley, R.; Slater, T.; Morgan, H.; Strange, H.; Scourfield, J. Comparison of Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempt and Suicide in Children and Young People in Care and Non-Care Populations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.S. Enhancing the Lives of Children in Out-of-Home Care: An Exploration of Mind-Body Interventions as a Method of Trauma Recovery. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.P.; Greeson, J.K.P.; Zlotnik, S.R.; Chintapalli, L.K. Evidence-Based Practice for Youth in Supervised out-of-Home Care: A Framework for Development, Definition, and Evaluation. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 2009, 6, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, N.; Abram, F.; Burgess, H. Family Group Conferences: Evidence, Outcomes and Future Research. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2014, 19, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, M.; Petermann, F. Attachment, Development, and Mental Health in Abused and Neglected Preschool Children in Foster Care: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Kayed, N.S. Children Placed in Alternate Care in Norway: A Review of Mental Health Needs and Current Official Measures to Meet Them. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2018, 27, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, S.; Donnelly, M.; Onyeka, I.N.; O’Reilly, D.; Maguire, A. Experience of Child Welfare Services and Long-Term Adult Mental Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1115–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, B.H.; Blakeslee, J.; Miller, R. Individual and Interpersonal Factors Associated with Psychosocial Functioning among Adolescents in Foster Care: A Scoping Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelick, A. Research Review: Independent Living Programmes: The Influence on Youth Ageing out of Care (YAO). Child Fam. Soc. Work 2015, 22, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.; Romano, E. Permanency and Safety among Children in Foster Family and Kinship Care: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 18, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehal, N. Maltreatment in Foster Care: A Review of the Evidence. Child Abus. Rev. 2014, 23, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuit, N.; Ryke, E.H. A Rapid Review of Non-Death Bereavement Interventions for Children in Alternative Care. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, A.T.; Köngeter, S.; Zeller, M.; Knorth, E.J.; Knot-Dickscheit, J. Instruments for Research on Transition: Applied Methods and Approaches for Exploring the Transition of Young Care Leavers to Adulthood. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 2431–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekoni, T.; Miettinen, J.; Häkälä, N.; Savolainen, A. Child Development in Foster Family Care—What Really Counts? Eur. J. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, P.A.; Mannering, A.M.; Van Scoyoc, A.; Graham, A.M. A Translational Neuroscience Perspective on the Importance of Reducing Placement Instability among Foster Children. Child Welf. 2013, 92, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.L. Integrative Review: Delivery of Healthcare Services to Adolescents and Young Adults during and after Foster Care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, C.M.; Cook-Cottone, C.; Beck-Joslyn, M. An Overview of Problematic Eating and Food-Related Behavior among Foster Children: Definitions, Etiology, and Intervention. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2012, 29, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Heifetz, M.; Bohr, Y. Pregnancy and Motherhood among Adolescent Girls in Child Protective Services: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. J. Public Child Welf. 2012, 6, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, T.; Granqvist, P.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Sagi-Schwartz, A.; Glaser, D.; Steele, M.; Hammarlund, M.; Schuengel, C.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Steele, H.; et al. Attachment Goes to Court: Child Protection and Custody Issues. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, A.M. An Integrated Model for Counselor Social Justice Advocacy in Child Welfare. Fam. J. 2017, 25, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, S.A.; Lynch, A.; Zlotnik, S.; Matone, M.; Kreider, A.; Noonan, K. Mental Health, Behavioral and Developmental Issues for Youth in Foster Care. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2015, 45, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Sen, R. Improving Outcomes for Looked after Children: A Critical Analysis of Kinship Care. Practice 2014, 26, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, T.; Wrenn, A.; Kaye, H.; Priester, M.A.; Colombo, G.; Carter, K.; Shadreck, I.; Hargett, B.A.; Williams, J.A.; Coakley, T. Psychosocial Factors and Behavioral Health Outcomes among Children in Foster and Kinship Care: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 90, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, Z.; Calleja, N.G. Understanding the Use of Psychotropic Medications in the Child Welfare System: Causes, Consequences, and Proposed Solutions. Child Welf. 2012, 91, 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, D.; Schlösser, A. Interventions in Foster and Kinship Care: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 429–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesh, A.; Cui, M. Foster Parent Training Programmes for Foster Youth: A Content Review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldfogel, J. Rethinking the Paradigm for Child Protection. Future Child. 1998, 8, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Goldman, P.S.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Bradford, B.; Christopoulos, A.; Ken, P.L.A.; Cuthbert, C.; Duchinsky, R.; Fox, N.A.; Grigoras, S.; Gunnar, M.R.; et al. Institutionalisation and Deinstitutionalisation of Children 2: Policy and Practice Recommendations for Global, National, and Local Actors. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 606–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, S.A.; Gershoff, E.T. Foster Care: How We Can, and Should, Do More for Maltreated Children. Soc. Policy Rep. 2020, 33, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macvean, M.L.; Humphreys, C.; Healey, L. Facilitating the Collaborative Interface between Child Protection and Specialist Domestic Violence Services: A Scoping Review. Aust. Soc. Work 2018, 71, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, I.N.; Keeney, A.J. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Interagency and Cross-System Collaborations in the United States to Improve Child Welfare Outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J.L.; Bromfield, L. Evidence for the Efficacy of the Child Advocacy Center Model A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 17, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J.L.; Bromfield, L. Multi-Disciplinary Teams Responding to Child Abuse: Common Features and Assumptions. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 106, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbakkers, A.; Van Der Steen, S.; Grietens, H. The Needs of Foster Children and How to Satisfy Them: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, R.; Hodes, M. Prevention of Psychological Distress and Promotion of Resilience amongst Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Resettlement Countries. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, S.A.; Fortin, K. Physical Health Problems and Barriers to Optimal Health Care among Children in Foster Care. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2015, 45, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, T.; Hjern, A.; Håkanson, K.; Johansson, P.; Jonsson, A.K.; Mattsson, T.; Tranæus, S.; Vinnerljung, B.; Östlund, P.; Klingberg, G. Organisational Models of Health Services for Children and Adolescents in Out-of-home Care: Health Technology Assessment. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Skouteris, H.; Hemmingsson, E.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Hardy, L.L. Problematic Eating and Food-Related Behaviours and Excessive Weight Gain: Why Children in out-of-Home Care Are at Risk. Aust. Soc. Work 2016, 69, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, A.; Assink, M.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; van der Put, C. Safety Assessment in Child Welfare: A Comparison of Instruments. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, S.A.; Lauritzen, C.; Fossum, S. Systematic Approaches to Assessment in Child Protection Investigations: A Literature Review. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccaro-Alamin, S.; Foust, R.; Vaithianathan, R.; Putnam-Hornstein, E. Risk Assessment and Decision Making in Child Protective Services: Predictive Risk Modeling in Context. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Farrell, A.F.; Marcal, K.E.; Chung, S.; Hovmand, P.S. Housing and Child Welfare: Emerging Evidence and Implications for Scaling up Services. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 60, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, J.M.; Beltran, S.J. Readiness, Access, Preparation, and Support for Foster Care Alumni in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature. J. Public Child Welf. 2017, 11, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, D.; Brady, B.; Forkan, C. Supporting Children’s Participation in Decision Making: A Systematic Literature Review Exploring the Effectiveness of Participatory Processes. Br. J. Soc. Work 2018, 48, 1985–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckock, B.; Barlow, J.; Brown, C. Developing Innovative Models of Practice at the Interface between the NHS and Child and Family Social Work Where Children Living at Home Are at Risk of Abuse and Neglect: A Scoping Review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2015, 22, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpetis, G. Theories on Child Protection Work with Parents: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Child Welf. 2017, 95, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, G.; Turney, D.; Ward, A. Relationship-Based Social Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84905-003-6. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D.; Duggan, M.; Joseph, S. Relationship-Based Social Work and Its Compatibility with the Person-Centred Approach: Principled versus Instrumental Perspectives. Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 43, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonzaaier, E.; Truter, E.; Fouché, A. Occupational Risk Factors in Child Protection Social Work: A Scoping Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 123, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.S.; Hetland, H.; Hystad, S.W.; Iversen, A.C.; Ortiz-Barreda, G. Lean on Me: A Scoping Review of the Essence of Workplace Support among Child Welfare Workers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, D.J.; Radey, M.; King, E.; Spinelli, C.; Rakes, S.; Nolan, C.R. A Multi-Level Conceptual Model to Examine Child Welfare Worker Turnover and Retention Decisions. J. Public Child Welf. 2018, 12, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kao, D. A Meta-Analysis of Turnover Intention Predictors among U.S. Child Welfare Workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 47, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, P.; Campbell, A.; Taylor, B. Resilience and Burnout in Child Protection Social Work: Individual and Organisational Themes from a Systematic Literature Review. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, 1546–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, W.W.; Steib, S.D. The Organizational Structure of Child Welfare: Staff Are Working Hard, but It Is Hardly Working. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 44, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogo, M.; Shlonsky, A.; Lee, B.; Serbinski, S. Acting like It Matters: A Scoping Review of Simulation in Child Welfare Training. J. Public Child Welf. 2014, 8, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.E.; Kim, S.H.; Amodeo, M. Empirical Studies of Child Welfare Training Effectiveness: Methods and Outcomes. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2010, 27, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.P.; Berrick, J.D.; Garcia, A.R.; Drake, B.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Gyourko, J.R.; Greeson, J.K.P. Research to Consider While Effectively Re-Designing Child Welfare Services. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2022, 32, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, C.; Hegarty, K.; d’Oliveira, A.F.L.; Koziol-McLain, J.; Colombini, M.; Feder, G. The Health-Systems Response to Violence against Women. Lancet 2015, 385, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, C. Indigenous Child Welfare Legislation: A Historical Change or Another Paper Tiger? First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2019, 14, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, C.; Bamblett, M.; Black, C. Indigenous Ontology, International Law and the Application of the Convention to the over-Representation of Indigenous Children in out of Home Care in Canada and Australia. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Children, youth (0–25 years of age) and families with prior or current involvement with child welfare. |

| Concept | Study author recommendations to improve child welfare at the societal-level (e.g., policy), community-level (e.g., coordination of services), institutional-level (e.g., child welfare initiatives), relationship-level (e.g., social worker skills), and individual-level (e.g., training). |

| Context | Peer-reviewed reviews that summarized recommendations to improve child welfare in high-income countries. Reviews could include systematic reviews, meta-analyses, qualitative reviews (e.g., meta-syntheses), rapid reviews, scoping reviews, and narrative reviews. |

| Timeline | 2010 to 2021 (when the search was conducted) |

| Example of Database Search Strategy |

|---|

| Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to June 04, 2021> Search Strategy: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Child Protective Services/ (602) 2 (child * adj3 (welfare or aid)).tw, kw. (5015) 3 (child * protect * adj3 (service? or agenc * or organi?ation?)).tw, kw. (1560) 4 (“foster care” or “foster home?” or “residential care” or “kin care” or “kinship care”). tw. (6280) 5 (out-of-home adj3 (placement? or care)). tw. (894) 6 or/1-5 (12838) 7 exp child/ or exp infant/ (2552666) 8 (child * or girl or girls or boy or boys or infant * or baby or babies or toddler * or preschool * or pre-school * or “young person” or “young people” or teen * or adolescen * or youth *).tw. (2106256) 9 or/7-8 (3282693) 10 6 and 9 (9547) 11 meta-analysis/ or “systematic review”/ or review/ (2915611) 12 (review? or meta-analy * or metaanaly * or metasynthe * or meta-synthe * or (information adj2 synthesis) or (data adj2 synthesis)).tw. (1971484) 13 ((systematic or state-of-the-art or scoping or literature or umbrella) adj3 (review * or bibliographic * or overview * or assessment *)).tw. (512487) 14 “scoping study”.tw. (339) 15 or/11-14 (3640612) 16 10 and 15 (1374) 17 limit 16 to yr=”2010 -Current” (752) |

| Count 1 | |

|---|---|

| Narrative reviews | 249 |

| Systematic reviews | 118 |

| Scoping reviews | 31 |

| Meta-analyses | 23 |

| Integrative reviews | 8 |

| Rapid reviews | 5 |

| Meta-syntheses | 3 |

| Mapping review | 1 |

| Count 1 | |

|---|---|

| Involved with child welfare | 128 |

| 51 |

| 22 |

| 55 |

| Out-of-home care | 367 |

| 28 |

| 12 |

| 6 |

| 321 |

| ○ Out-of-home care | 57 |

| ○ Foster care | 141 |

| ○ Kinship care | 83 |

| ○ Residential care | 24 |

| ○ Adoption | 16 |

| Child welfare organizations | 57 |

| Child welfare professionals | 46 |

| Interdisciplinary focus | 22 |

| Count 2 | |

|---|---|

| Society—laws and policies | |

| Cross-country analysis of aspects of child welfare | 20 |

| International actors influencing child welfare | 15 |

| Human rights | 7 |

| National child welfare structure | 68 |

| National child welfare policies and legislation | 51 |

| Systemic disadvantage in child welfare | 47 |

| National institutional actors influencing child welfare | 11 |

| Community—relationships among organizations, institutions and informal networks | |

| Collaboration models, strategies, and components | 40 |

| Institution—characteristics and rules for operations | |

| Child welfare organizational policies, procedures, and overall environment | 38 |

| Child welfare workforce | 17 |

| Child welfare organizational performance and evaluation | 12 |

| Professional support for child welfare professionals | 9 |

| Interventions, services, programs and outcomes associated with different sectors | |

| 252 |

| ○ Placement | 94 |

| ○ Biological family | 64 |

| ○ Usage of child welfare services | 52 |

| ○ Participation in child welfare | 48 |

| ○ Transition from care | 46 |

| ○ Safety | 42 |

| ○ Foster/kinship care (as a service) | 41 |

| 197 |

| ○ Mental health | 121 |

| ○ Social health | 79 |

| ○ Physical health | 69 |

| ○ Usage of health services | 22 |

| 41 |

| 22 |

| 21 |

| 19 |

| Individual—knowledge, attitudes, skills, etc. | |

| Child welfare professionals | |

| 38 |

| 23 |

| 13 |

| 7 |

| Foster/kinship carers | |

| 40 |

| 15 |

| Count 2 | |

|---|---|

| Society—laws and policies | |

| Political (policy/legislative) support and associated funding for child welfare | 56 |

| Need for holistic, not fragmented policies | 52 |

| Address systemic disadvantages | 46 |

| Youth voices in decision-making and policies | 24 |

| Community—relationships among organizations, institutions and informal networks | |

| Multi- and inter-disciplinary collaboration and coordination | 118 |

| Increased access to services | 67 |

| Cross-disciplinary training | 35 |

| Information sharing | 22 |

| Institution—institutional characteristics and rules for operations | |

| Cross-disciplinary focus | |

| |

| ○ Ethnically/racially diverse families and children | 59 |

| ○ Families experiencing substance use/mental health concerns | 43 |

| ○ Youth transitioning from care | 28 |

| ○ Families experiencing low socioeconomic status | 20 |

| ○ Children with complex needs (such as chronic illness, disability or sensory impairment and needs additional support on a daily basis) | 15 |

| ○ Families experiencing intimate partner violence | 11 |

| ○ LGBTQ+ families and children | 6 |

| |

| ○ Evidence-based/effective | 87 |

| ○ Tailored (specific to needs of family/child) | 64 |

| ○ Culturally sensitive/appropriate/safe | 58 |

| ○ Preventative approach | 47 |

| ○ Developmentally sensitive/age appropriate | 44 |

| ○ Trauma-informed | 44 |

| ○ Comprehensive | 37 |

| ○ Strengths-based | 23 |

| |

| ○ Robust research (randomized controlled trials/longitudinal) | 155 |

| ○ Qualitative research (voices of children, youth, and families) | 66 |

| Relationships—formal and informal relationships | |

| Improving relationships with families/children or assistance for families/children through: | |

| 104 |

| 83 |

| 30 |

| 25 |

| Individual—knowledge, attitudes, skills, etc. | |

| Training for healthcare, social service providers (including child welfare professionals), and foster carers | |

| 108 |

| 18 |

| 12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McTavish, J.R.; McKee, C.; Tanaka, M.; MacMillan, H.L. Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114071

McTavish JR, McKee C, Tanaka M, MacMillan HL. Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114071

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcTavish, Jill R., Christine McKee, Masako Tanaka, and Harriet L. MacMillan. 2022. "Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114071

APA StyleMcTavish, J. R., McKee, C., Tanaka, M., & MacMillan, H. L. (2022). Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114071