Self-Medication Behaviors of Chinese Residents and Consideration Related to Drug Prices and Medical Insurance Reimbursement When Self-Medicating: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

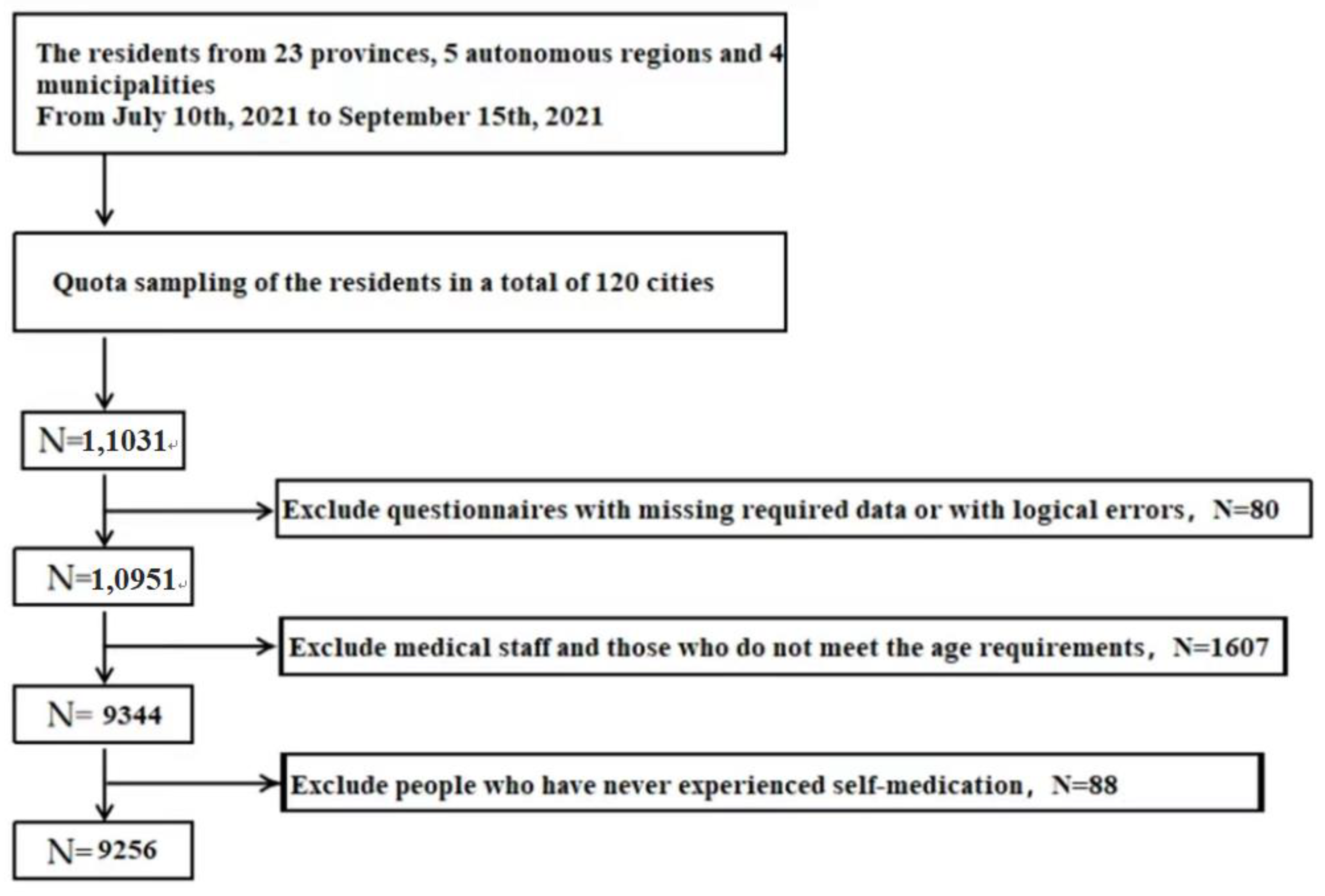

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Calculation of Minimum Sample Size

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. The General Clinical and Demographic Information

2.3.2. Items for Resident Self-Medication Status and Important Considerations

2.3.3. The 10-Item Short Version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-10)

2.3.4. The Short-Form Health Literacy Instrument (HLS-SF12)

2.4. Statistical Methods

2.5. Quality Control

3. Results

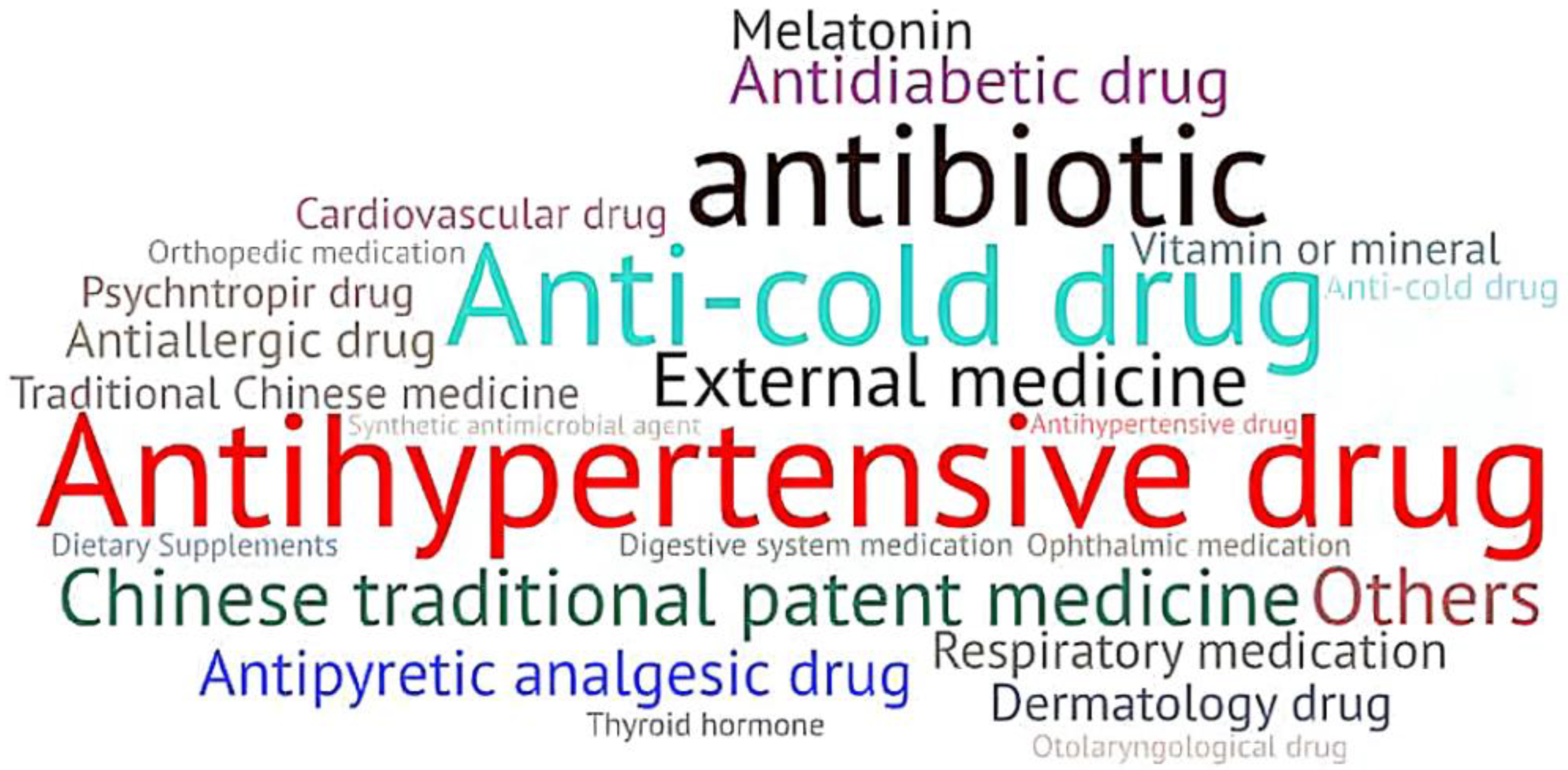

3.1. Information of Self-Medication of Respondents

3.2. The Score of Each Scale of the Respondents

3.3. Univariate Analysis of Respondents’ Considerations When Self-Purchasing OTC Drugs

3.4. Multivariate Binary Stepwise Logistic Regression Analysis of Two Factors of Medical Insurance Reimbursement or Drug Price

3.4.1. Medical Insurance Reimbursement

3.4.2. Drug Price

4. Discussion

4.1. Considerations

4.1.1. Drug Price

4.1.2. Medical Insurance Reimbursement

4.1.3. Comprehensive Drug Price and Medical Insurance Reimbursement

4.2. Suggestions

4.3. Advantages and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Role of the Pharmacist in Self-Care and Self-Medication: Report of the 4th WHO Consultative Group on the Role of the Pharmacist; World Health Organization: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998.

- World Self-Medication Industry (WSMI). What Is Self-Medication. Available online: https://www.wsmi.org/what-is-self-care (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Quincho-Lopez, A.; Benites-Ibarra, C.A.; Hilario-Gomez, M.M.; Quijano-Escate, R.; Taype-Rondan, A. Self-medication practices to prevent or manage COVID-19: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, A.D.; Bifftu, B.B.; Mekonnen, H.S. Self-medication practice and associated factors among adult household members in Meket district, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, I.S.; Chaw, L.L.; Koh, D.; Hussain, Z.; Goh, K.W.; Abdul, H.A.A.; Ming, L.C. Over-the-Counter Medicine Attitudes and Knowledge among University and College Students in Brunei Darussalam: Findings from the First National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skliros, E.; Merkouris, P.; Papazafiropoulou, A.; Gikas, A.; Matzouranis, G.; Papafragos, C.; Tsakanikas, I.; Zarbala, I.; Vasibosis, A.; Stamataki, P.; et al. Self-medication with antibiotics in rural population in Greece: A cross-sectional multicenter study. BMC Fam. Pr. 2010, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.H.; Lv, J.; Han, L.; Zhu, Z.; Tian, Y. Research on safe drug use education in the context of “Healthy China”. Chin. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2017, 10, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, J.P. Medical care costs: How much welfare loss? J. Econ. Perspect. 1992, 6, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Du, T.; Hu, Y. The Effect of Population Aging on Healthcare Expenditure from a Healthcare Demand Perspective Among Different Age Groups: Evidence from Beijing City in the People’s Republic of China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, C. The Impact of Dependency Burden on Urban Household Health Expenditure and Its Regional Heterogeneity in China: Based on Quantile Regression Method. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 876088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepehri, A.; Vu, P.H. Severe injuries and household catastrophic health expenditure in Vietnam: Findings from the Household Living Standard Survey 2014. Public Health 2019, 174, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Hu, Y.; Artnik, B.; Bopp, M.; Costa, G.; Kalediene, R.; Martikainen, P.; Menvielle, G.; Strand, B.H.; Wojtyniak, B.; et al. Trends In Inequalities In Mortality Amenable To Health Care In 17 European Countries. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2017, 36, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwabu, G.; Ainsworth, M.; Nyamete, A. Quality of medical care and choice of medical treatment in Kenya: An empirical analysis. J. Human Res. 1993, 28, 838–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, V.R. Health care for the elderly: How much? Who will pay for it? Health Affairs (Millwood) 1999, 18, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, M.M.; Masood, I.; Yousaf, M.; Saleem, H.; Ye, D.; Fang, Y. Pattern of medication selling and self-medication practices: A study from Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yan, B. A study on the level of awareness and factors influencing parents’ self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in children. J. Army Med. Univ. 2022, 44, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortsberg, C. Why do the sick not utilise health care? The case of Zambia. Health Econ. 2003, 12, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P.P.; Jin, J.Y.; Min, S.; Wang, W.J.; Shen, Y.W. Association Between Health Literacy and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Adherence and Postoperative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Anesth. Analg. 2022, 134, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ge, P.; Li, X.; Yin, M.; Wang, Y.; Ming, W.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y. Personality Effects on Chinese Public Preference for the COVID-19 Vaccination: Discrete Choice Experiment and Latent Profile Analysis Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, T.C.; Bruce, D.G.; Davis, T.M.; Davis, W.A. Personality traits, self-care behaviours and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: The Fremantle diabetes study phase II. Diabet. Med. 2014, 31, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurd, M.D.; McGarry, K. Medical insurance and the use of health care services by the elderly. J. Health Econ. 1997, 16, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, A. Supplementary private health insurance and health care utilization of people aged 50+. Empir. Econ. 2014, 46, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavosi, Z.; Keshtkaran, A.; Hayati, R.; Ravangard, R.; Khammarnia, M. Household financial contribution to the health System in Shiraz, Iran in 2012. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 3, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, M.; Huang, L.; Nuse, B. Depressive costs: Medical expenditures on depression and depressive symptoms among rural elderly in China. Public Health 2020, 181, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.G.; Vortherms, S.A.; Hong, X. China’s Health Reform Update. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y.; Shi, L. An analysis of China’s National Essential Medicines policy. J. Public Health Policy 2011, 32, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.; Jiang, W.X.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, J.; Tang, S.L.; Wang, W.B. Multi-source financing for tuberculosis treatment in China: Key issues and challenges. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Fu, H.; Chen, A.T.; Zhai, T.; Jian, W.; Xu, R.; Pan, J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet 2019, 394, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, H.J.; Wang, H.J.; Luo, B.; Wang, S.H. An Investigation Study on Residents’ Home Self-Pharmacological Behavior in Gansu Province Based on the Greene Model. Chin. Pharm. 2020, 31, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onchonga, D. A Google Trends study on the interest in self-medication during the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) disease pandemic. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, G.; Bhatta, S. Self-medication with Antibiotics in WHO Southeast Asian Region: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, J.; Yibo, W.; Ling, Z.; Lina, L.; Xinying, S. Health Literacy and Personality Traits in Two Types of Family Structure-A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 835909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Bulletin of the Seventh National Census. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/search/s?qt=第七次人口普查 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Samo, A.A.; Sayed, R.B.; Valecha, J.; Baig, N.M.; Laghari, Z.A. Demographic factors associated with acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal of COVID-19 vaccine among residents of Sukkur during lockdown: A cross sectional study from Pakistan. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2026137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Chen, X.Y. Reliability and validity of General Self-efficacy Scale (NGSES). J. Mudanjiang Norm. Univ. 2012, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calamusa, A.; Di Marzio, A.; Cristofani, R.; Arrighetti, P.; Santaniello, V.; Alfani, S.; Carducci, A. Factors that influence Italian consumers’ understanding of over-the-counter medicines and risk perception. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yan, J.Z.; Shao, R. A comparative study on the management system of OTC drugs between China and the United States. Chin. J. New Drugs 2019, 28, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Ren, L.; Wirtz, V. How much could be saved in Chinese hospitals in procurement of anti-hypertensives and anti-diabetics? J. Med. Econ. 2016, 19, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; Leufkens, H.G.; Laing, R.O. Switching from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents in selected developing countries: How much could be saved? Value Health 2012, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W. A price and use comparison of generic versus originator cardiovascular medicines: A hospital study in Chongqing, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hu, C.J.; Stuntz, M.; Hogerzeil, H.; Liu, Y. A review of promoting access to medicines in China-problems and recommendations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, S.S.; Dunne, C.P. What do people really think of generic medicines? A systematic review and critical appraisal of literature on stakeholder perceptions of generic drugs. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Linden, K.; Kääriä, K. Patients’ Preferences for Generic and Branded Over-the-Counter Medicines: An Adaptive Conjoint Analysis Approach. Patient 2009, 2, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, A.I. Self-medication model and evidence from Portugal. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2013, 40, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z. Socioeconomic determinants of out-of-pocket pharmaceutical expenditure among middle-aged and elderly adults based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal investigation. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanwald, A.; Theurl, E. Out-of-pocket expenditures for pharmaceuticals: Lessons from the Austrian household budget investigation. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, I. Self-care Continues to Fuel OTC Drug Market. Drug Topics 1986, 9, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Deng, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y. Medical insurance and health equity in health service utilization among the middle-aged and older adults in China: A quantile regression approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wong, H.; Liu, K. Outcome-based health equity across different social health insurance schemes for the elderly in China. BMC Health Serv. Res 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, C.C. Health service utilization and expenditure of the elderly in China. Asian Soc. Work Pol. Rev. 2016, 10, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.H.; Lee, W.J.; Chen, L.K.; Hsiao, F.Y. Comparisons of annual health care utilization, drug consumption, and medical expenditure between the elderly and general population in Taiwan. J. Clin. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 7, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kwon, J.W.; Lee, E.K.; Jung, Y.H.; Park, S. Out-Of-Pocket medication expenditure burden of elderly Koreans with chronic conditions. Int. J. Gerontol. 2015, 9, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Faraji, A.; Dehghan, F.; Khatony, A. Prevalence of self-medication practice among health sciences students in Kermanshah, Iran. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.Y.; Yang, H.W.; Chen, W.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.Y. People’s Republic of China health system review: WHO regional office for the western pacific. Health Syst. Transit. 2015, 5, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Q.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, H.; Ling, L. Social health insurance coverage and financial protection among rural-to-urban internal migrants in China: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefford, M.; Safford, M.M.; Muntner, P.; Durant, R.W.; Brown, T.M.; Levitan, E.B. Insurance, self-reported medication adherence and LDL cholesterol: The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 236, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heide, I.; Wang, J.; Droomers, M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Rademakers, J.; Uiters, E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: Results from the Dutch Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. S1), 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Lai, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, T.; Wu, Y. Effects of an mHealth Intervention for Pulmonary Tuberculosis Self-management Based on the Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 14, 34277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Z.; Li, S. Barriers to medication adherence for rural patients with mental disorders in eastern China: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Lu, W.; Mao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ming, W.K.; Wu, Y. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding health self-management among patients with osteogenesis imperfecta in China: An online cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2021, 27, 046286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Part | Table Contents | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| The general clinical and demographic information | Gender, age, province, place of permanent residence, education level, per capita monthly income of the family, marital status, the current main way of bearing medical expenses, current occupational status, and currently diagnosed chronic diseases | Collect general demographic information |

| Items for Resident Self-Medication Status and Important Considerations | This part includes 3 questions, “Have you ever purchased and used OTC medicines on your own?”, “What kinds of OTC drugs have you ever purchased and used?”, “Which of the following factors are important considerations when purchasing OTC drugs?” | Collect self-medication behavior and considerations |

| BFI-10 | The scale consists of 10 entries divided into five dimensions: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness, with each dimension containing two entries | Measure the personality traits of the respondents |

| HLS-SF12 | The scale includes 3 dimensions of health care, disease prevention, and health promotion, with a total of 12 items. | Measure the health literacy of the investigation respondents |

| No. of Items | Score Range | Kolmogorow–Smironov Z | p Value from the K-S Test | Median | Lower Quartile—Upper Quartile | High Score Group | Low Score Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLS—SF12 | 12 | 0–50 | 0.208 | <0.001 | 33.33 | 30.56–37.50 | 5942 (64.20%) | 3314 (35.80%) |

| BFI-10 | ||||||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 2–10 | 0.203 | <0.001 | 6 | 5–7 | 3349 (36.18%) | 5907 (63.82%) |

| Agreeableness | 2 | 2–10 | 0.187 | <0.001 | 7 | 6–8 | 5182 (55.99%) | 4074 (44.01%) |

| Conscientiousness | 2 | 2–10 | 0.200 | <0.001 | 7 | 6–8 | 4757 (51.39%) | 4499 (48.61%) |

| Neuroticism | 2 | 2–10 | 0.217 | <0.001 | 6 | 5–6 | 2257 (24.38%) | 6999 (75.62%) |

| Openness | 2 | 2–10 | 0.221 | <0.001 | 6 | 6–7 | 3565 (38.52%) | 5691 (61.48%) |

| Number of Respondents (%) | Medicare Reimbursement as an Important Consideration | χ² (p) | Drug Price as an Important Consideration | χ² (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| Gender | 4.553 (0.033) | 1.321 (0.250) | |||||

| Male | 4289 (46.34) | 3019 (70.4) | 1270 (29.6) | 2653 (61.9) | 1636 (38.1) | ||

| Female | 4967 (53.66) | 3596 (72.4) | 1371 (27.6) | 3130 (63) | 1837 (37) | ||

| Age(years) | 116.266 (0.001) | 25.057 (<0.001) | |||||

| 19–35 | 4246 (45.87) | 3224 (75.9) | 1022 (24.1) | 2687 (63.3) | 1559 (36.7) | ||

| 36–59 | 3935 (42.51) | 2746 (69.8) | 1189 (30.2) | 2499 (63.5) | 1436 (36.5) | ||

| >60 | 1075 (11.61) | 645 (60) | 430 (40) | 597 (55.5) | 478 (44.5) | ||

| Education level | 29.98 (<0.001) | 82.066 (<0.001) | |||||

| High/Secondary School and lower | 3685 (39.81) | 2537 (68.8) | 1148 (31.2) | 2106 (57.2) | 1579 (42.8) | ||

| Junior college | 1300 (14.04) | 909 (69.9) | 391 (30.1) | 827 (63.6) | 473 (36.4) | ||

| Undergraduate | 3654 (39.48) | 2718 (74.4) | 936 (25.6) | 2460 (67.3) | 1194 (32.7) | ||

| Postgraduate degree (including master’s and PhD students) | 617 (6.67) | 451 (73.1) | 166 (26.9) | 390 (63.2) | 227 (36.8) | ||

| Location | 4.952 (0.084) | 35.321 (<0.001) | |||||

| Eastern part of China | 4722 (51.02) | 3423 (72.5) | 1299 (27.5) | 3080 (65.2) | 1642 (34.8) | ||

| Central part of China | 2391 (25.83) | 1684 (70.4) | 707 (29.6) | 1459 (61) | 932 (39) | ||

| Western part of China | 2143 (23.15) | 1508 (70.4) | 635 (29.6) | 1244 (58) | 899 (42) | ||

| Place of residence | 2.259 (0.133) | 62.524 (<0.001) | |||||

| Urban | 1840 (19.88) | 1816 (70.3) | 766 (29.7) | 1448 (56.1) | 1134 (43.9) | ||

| Rural | 4472 (48.31) | 4799 (71.9) | 1875 (28.1) | 4335 (65) | 2339 (35) | ||

| Marital status | 2944 (31.81) | 105.565 (<0.001) | 17.575 (0.001) | ||||

| Unmarried | 3946 (68.4) | 1819 (31.6) | 3629 (62.9) | 2136 (37.1) | |||

| Married | 6674 (72.1) | 2399 (78.1) | 673 (21.9) | 1915 (62.3) | 1157 (37.7) | ||

| Divorce | 2582 (27.9) | 133 (68.9) | 60 (31.1) | 127 (65.8) | 66 (34.2) | ||

| Widowed | 137 (60.6) | 89 (39.4) | 112 (49.6) | 114 (50.4) | |||

| Employment status | 4735 (51.16) | 121.292 (<0.001) | 77.424 (<0.001) | ||||

| Employed | 3146 (33.99) | 2883 (69.8) | 1246 (30.2) | 2751 (66.6) | 1378 (33.4) | ||

| Student | 1375 (14.86) | 1707 (79.6) | 437 (20.4) | 1327 (61.9) | 817 (38.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 1533 (70.5) | 641 (29.5) | 1204 (55.4) | 970 (44.6) | |||

| Retired | 5765 (62.28) | 492 (60.8) | 317 (39.2) | 501 (61.9) | 308 (38.1) | ||

| The main way of medical expenses borne | 3072 (33.19) | 105.436 (<0.001) | 48.319 (<0.001) | ||||

| Out-of-pocket payments | 193 (2.09) | 1482 (80.5) | 358 (19.5) | 1100 (59.8) | 740 (40.2) | ||

| Resident Basic Medical Insurance (RBMI) | 226 (2.44) | 3163 (70.7) | 1309 (29.3) | 2693 (60.2) | 1779 (39.8) | ||

| Other | 1970 (66.9) | 974 (33.1) | 1990 (67.6) | 954 (32.4) | |||

| Chronic diseases condition | 4129 (44.61) | 50.086 (<0.001) | 29.671 (<0.001) | ||||

| No | 2144 (23.16) | 5382 (73.2) | 1975 (26.8) | 4699 (63.9) | 2658 (36.1) | ||

| Yes | 2174 (23.49) | 1233 (64.9) | 666 (35.1) | 1084 (57.1) | 815 (42.9) | ||

| Monthly income (RMB) | 809 (8.74) | 13.656 (0.001) | 59.408 (<0.001) | ||||

| <4500 | 3388 (71.6) | 1347 (28.4) | 2783 (58.8) | 1952 (41.2) | |||

| 4501–9000 | 7357 (79.48) | 2194 (69.7) | 952 (30.3) | 2063 (65.6) | 1083 (34.4) | ||

| ≥9001 | 1899 (20.52) | 1033 (75.1) | 342 (24.9) | 937 (68.1) | 438 (31.9) | ||

| Extraversion | 0.168 (0.682) | 1.749 (0.186) | |||||

| High-score Group | 4735 (51.16) | 2402 (71.7) | 947 (28.3) | 2122 (63.4) | 1227 (36.6) | ||

| Low-score Group | 3146 (33.99) | 4213 (71.3) | 1694 (28.7) | 3661 (62) | 2246 (38) | ||

| Agreeableness | 1375 (14.86) | 0.119 (0.731) | 0.082 (0.774) | ||||

| High-score Group | 3696 (71.3) | 1486 (28.7) | 3231 (62.4) | 1951 (37.6) | |||

| Low-score Group | 3349 (36.18) | 2919 (71.6) | 1155 (28.4) | 2552 (62.6) | 1522 (37.4) | ||

| Conscientiousness | 5907 (63.82) | 16.310 (<0.001) | 0.806 (0.369) | ||||

| High-score Group | 3312 (69.6) | 1445 (30.4) | 2993 (62.9) | 1764 (37.1) | |||

| Low-score Group | 5182 (55.99) | 3303 (73.4) | 1196 (26.6) | 2790 (62) | 1709 (38) | ||

| Neuroticism | 4074 (44.01) | 0.930 (0.335) | 3.447 (0.063) | ||||

| High-score Group | 1631 (72.3) | 626 (27.7) | 1373 (60.8) | 884 (39.2) | |||

| Low-score Group | 4757 (51.39) | 4984 (71.2) | 2015 (28.8) | 4410 (63) | 2589 (37) | ||

| Openness | 4499 (48.61) | 9.220 (0.002) | 3.059 (0.080) | ||||

| High-score Group | 2612 (73.3) | 953 (26.7) | 2267 (63.6) | 1298 (36.4) | |||

| Low-score Group | 2257 (24.38) | 4003 (70.3) | 1688 (29.7) | 3516 (61.8) | 2175 (38.2) | ||

| Health literacy | 6999 (75.62) | 15.281 (<0.001) | 69.020 (<0.001) | ||||

| High-score Group | 4328 (72.8) | 1614 (27.2) | 3898 (65.6) | 2044 (34.4) | |||

| Low-score Group | 3565 (38.52) | 2287 (69) | 1027 (31) | 1885 (56.9) | 1429 (43.1) | ||

| Variables | β | SE | Wald χ² | p | OR | The Lower Limit of 95%CI | The Upper Limit of 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (control group = 19–35) | |||||||

| 36–58 | 0.086 | 0.061 | 1.99 | 0.158 | 1.09 | 0.967 | 1.228 |

| >60 | 0.473 | 0.102 | 21.45 | <0.001 | 1.605 | 1.314 | 1.960 |

| Location (control group = eastern part of China) | |||||||

| Central part of China | 0.131 | 0.057 | 5.359 | 0.021 | 1.140 | 1.020 | 1.275 |

| Western part of China | 0.115 | 0.059 | 3.769 | 0.052 | 1.121 | 0.999 | 1.259 |

| Employment status (control group = employed) | |||||||

| Student | −0.265 | 0.080 | 10.84 | 0.001 | 0.767 | 0.656 | 0.898 |

| Unemployed | −0.001 | 0.071 | 0 | 0.985 | 0.999 | 0.87 | 1.147 |

| Retire | 0.087 | 0.104 | 0.703 | 0.402 | 1.091 | 0.89 | 1.339 |

| The main way of medical expenses borne (control group = out-of-pocket payments) | |||||||

| Resident Basic Medical Insurance (RBMI) | 0.446 | 0.069 | 41.667 | <0.001 | 1.561 | 1.364 | 1.787 |

| Others | 0.625 | 0.08 | 60.225 | <0.001 | 1.867 | 1.595 | 2.187 |

| Monthly income (RMB) (control group = 0–4500) | |||||||

| 4501–9000 | 0.066 | 0.053 | 1.549 | 0.213 | 1.068 | 0.963 | 1.186 |

| ≥9001 | −0.163 | 0.073 | 4.951 | 0.026 | 0.849 | 0.736 | 0.981 |

| Health literacy (control group = high health literacy) | |||||||

| Low health literacy | 0.119 | 0.05 | 5.628 | 0.018 | 1.126 | 1.021 | 1.242 |

| Variables | β | SE | Wald χ² | p | OR | The Lower Limit of 95%CI | The Upper Limit of 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level (Control group = high/secondary school and lower) | |||||||

| Junior college | −0.106 | 0.071 | 2.239 | 0.135 | 0.9 | 0.783 | 1.033 |

| Undergraduate | −0.311 | 0.061 | 25.688 | <0.001 | 0.732 | 0.649 | 0.826 |

| Postgraduate degree (including master’s and PhD students) | −0.007 | 0.099 | 0.005 | 0.944 | 0.993 | 0.818 | 1.206 |

| Location (control group = eastern part of China) | |||||||

| Central part of China | 0.127 | 0.053 | 5.701 | 0.017 | 1.135 | 1.023 | 1.259 |

| Western part of China | 0.224 | 0.055 | 16.807 | <0.001 | 1.251 | 1.124 | 1.393 |

| Place of residence (control group = urban) | |||||||

| Rural | −0.188 | 0.052 | 13.15 | <0.001 | 0.828 | 0.748 | 0.917 |

| Employment status (control group = employed) | |||||||

| Student | 0.283 | 0.061 | 21.565 | <0.001 | 1.327 | 1.177 | 1.495 |

| Unemployed | 0.173 | 0.062 | 7.779 | 0.005 | 1.189 | 1.053 | 1.344 |

| Retire | −0.041 | 0.086 | 0.228 | 0.633 | 0.96 | 0.811 | 1.136 |

| Chronic diseases condition (control group = no) | |||||||

| Yes | 0.195 | 0.057 | 11.5 | 0.001 | 1.215 | 1.086 | 1.360 |

| Monthly income (RMB) (control group = 0–4500) | |||||||

| 4501–9000 | −0.104 | 0.051 | 4.143 | 0.042 | 0.901 | 0.815 | 0.996 |

| ≥9001 | −0.177 | 0.07 | 6.425 | 0.011 | 0.838 | 0.730 | 0.961 |

| Health literacy (control group = high health literacy) | |||||||

| Low health literacy | 0.235 | 0.047 | 25.074 | <0.001 | 1.265 | 1.154 | 1.387 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Ge, P.; Yan, M.; Niu, Y.; Liu, D.; Xiong, P.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Sun, X.; et al. Self-Medication Behaviors of Chinese Residents and Consideration Related to Drug Prices and Medical Insurance Reimbursement When Self-Medicating: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113754

Zhang Z, Ge P, Yan M, Niu Y, Liu D, Xiong P, Li Q, Zhang J, Yu W, Sun X, et al. Self-Medication Behaviors of Chinese Residents and Consideration Related to Drug Prices and Medical Insurance Reimbursement When Self-Medicating: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113754

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ziwei, Pu Ge, Mengyao Yan, Yuyao Niu, Diyue Liu, Ping Xiong, Qiyu Li, Jinzi Zhang, Wenli Yu, Xinying Sun, and et al. 2022. "Self-Medication Behaviors of Chinese Residents and Consideration Related to Drug Prices and Medical Insurance Reimbursement When Self-Medicating: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113754

APA StyleZhang, Z., Ge, P., Yan, M., Niu, Y., Liu, D., Xiong, P., Li, Q., Zhang, J., Yu, W., Sun, X., Liu, Z., & Wu, Y. (2022). Self-Medication Behaviors of Chinese Residents and Consideration Related to Drug Prices and Medical Insurance Reimbursement When Self-Medicating: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113754