Comparison between Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in Their Past Attempts and Intentions to Quit: Analysis of Two Rounds of a National Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

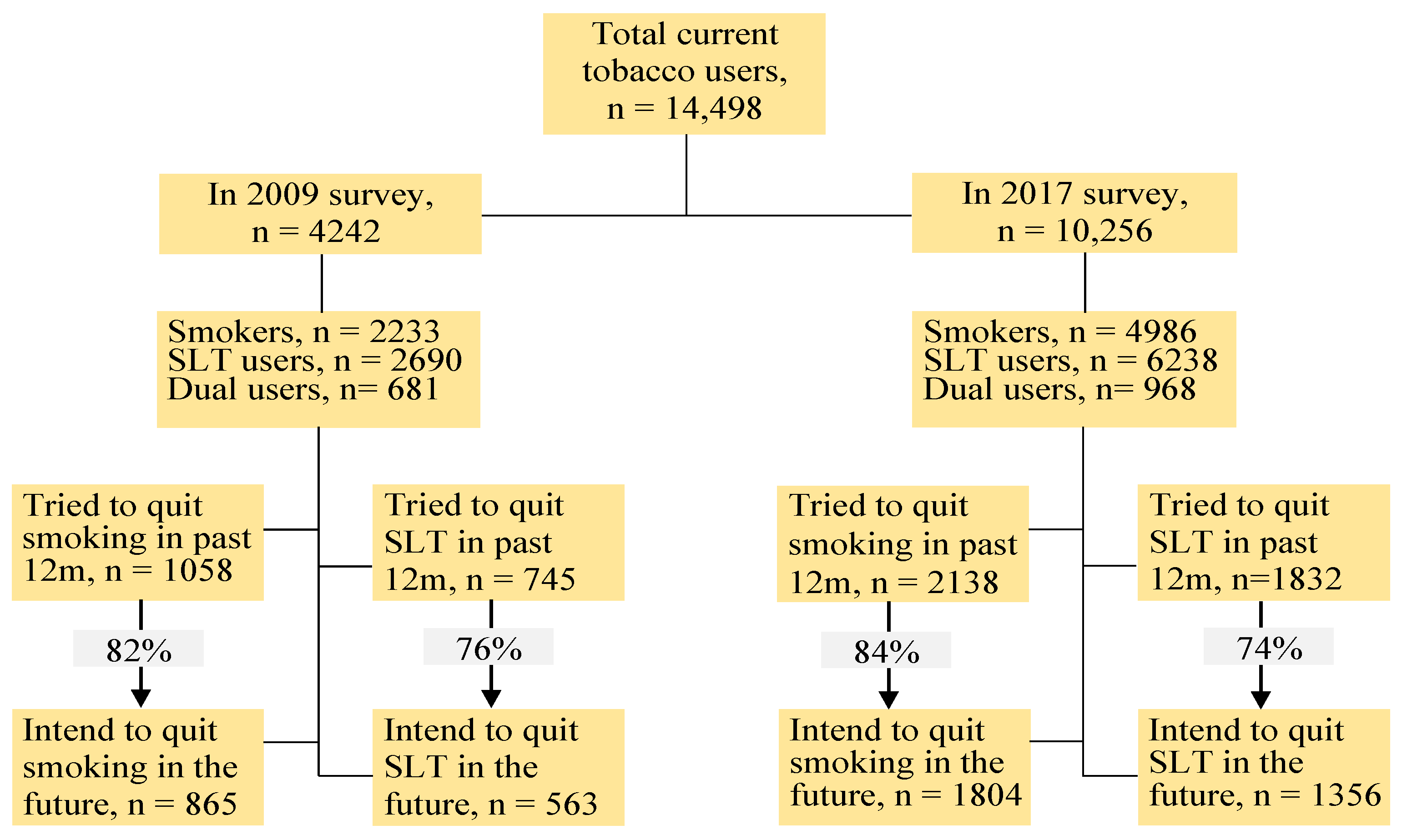

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Dependent and Independent Variables

2.3. Other Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

- (i)

- quitting attempts regarding smoking or SLT use in the 12 months prior to the surveys (outcome variable) and the type of tobacco use (study factor);

- (ii)

- intention to quit smoking or SLT use in the future (outcome variable) and the type of tobacco use (study factor);

- (iii)

- intention to quit smoking in the future (outcome variable) and attempts to quit smoking in the 12 months before the surveys; and

- (iv)

- intention to quit SLT use in the future (outcome variable) and attempts to quit SLT use in the 12 months before the surveys.

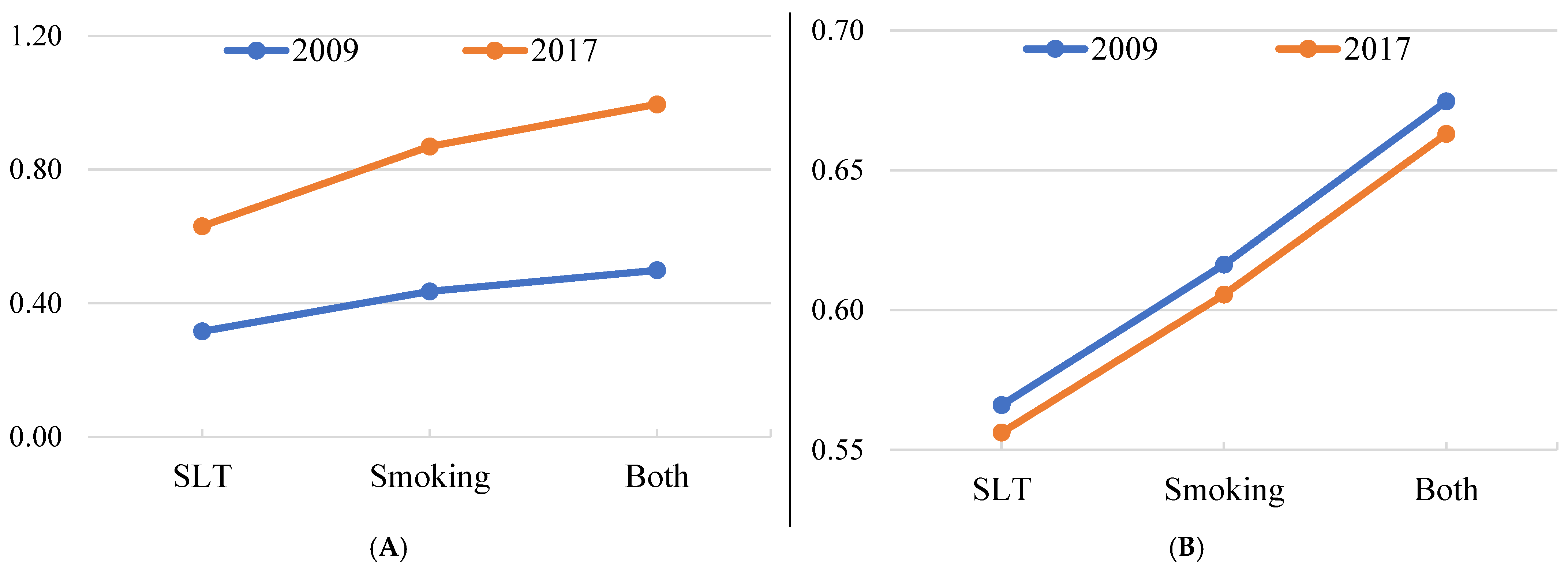

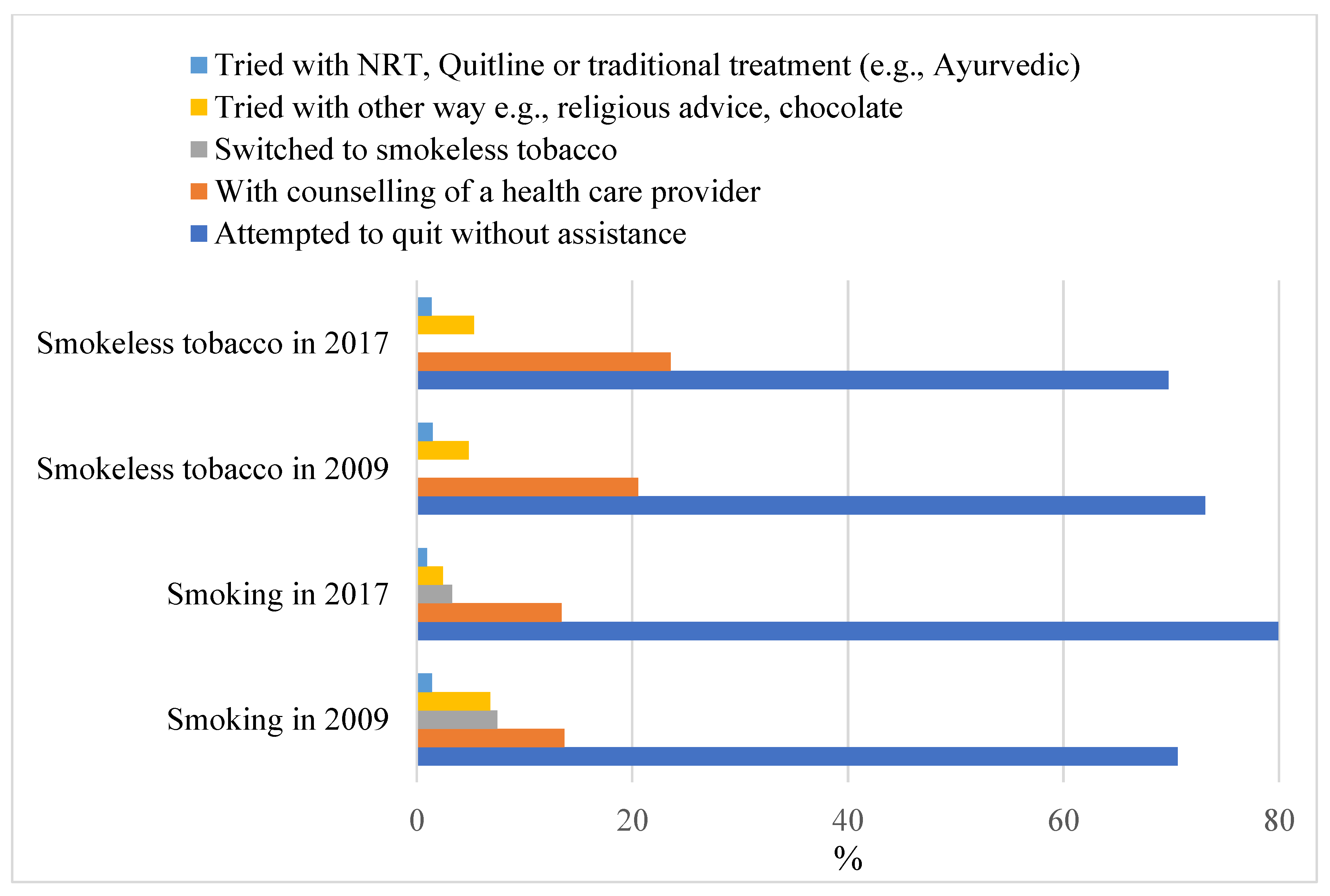

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maps of World. Top 10 Tobacco Producing Countries. Available online: https://www.mapsofworld.com/world-top-ten/tobacco-producing-countries.html (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Sreeramareddy, C.T.; Aye, S.N. Changes in adult smoking behaviours in ten global adult tobacco survey (GATS) countries during 2008-2018—A test of ‘hardening’ hypothesis’. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M. Daily users of both smoked and smokeless tobacco and their efforts to quit. J. Subst. Use 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and National Tobacco Control Cell. Global Adult Tobacco Survey Bangladesh Report 2017; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and National Tobacco Control Cell: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2019.

- Raw, M.; Ayo-Yusuf, O.; Chaloupka, F.; Fiore, M.; Glynn, T.; Hawari, F.; Mackay, J.; McNeill, A.; Reddy, S. Recommendations for the implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 14 on tobacco cessation support. Addiction 2017, 112, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, S.; Chowdhury, M.A.B.; Uddin, M.J. Correlates of unsuccessful smoking cessation among adults in Bangladesh. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 8, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiton, M.; Diemert, L.; Cohen, J.E.; Bondy, S.J.; Selby, P.; Philipneri, A.; Schwartz, R. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layoun, N.; Hallit, S.; Waked, M.; Aoun Bacha, Z.; Godin, I.; Dramaix, M.; Salameh, P. Predictors of Readiness to Quit Stages and Intention to Quit Cigarette Smoking in 2 and 6 Months in Lebanon. J. Res. Health Sci. 2017, 17, e00379. [Google Scholar]

- Jardin, B.F.; Carpenter, M.J. Predictors of quit attempts and abstinence among smokers not currently interested in quitting. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, J.; Borland, R.; Burney, S. The influence of having a quit date on prediction of smoking cessation outcome. Health Educ. Res. 2010, 25, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.; Arokiasamy, P. Identifying stages of smoke and smokeless tobacco cessation among adults in India: An application of transtheoretical model. J. Subst. Use 2021, 26, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, B.W.; Cheng, J. Cigarette and Smokeless Tobacco Perception Differences of Rural Male Youth. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2018, 4, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kypriotakis, G.; Robinson, J.D.; Green, C.E.; Cinciripini, P.M. Patterns of Tobacco Product Use and Correlates Among Adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study: A Latent Class Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, S81–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Fong, G.T.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Quah, A.C.; Sirirassamee, B.; Omar, M.; Zanna, M.P.; Fotuhi, O. Predictors of smoking cessation among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12 (Suppl. 1), S34–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Nonnemaker, J.; Sherrill, B.; Gilsenan, A.W.; Coste, F.; West, R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: Factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Seo, D.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.G.; Cho, S.-I.; Lee, S.; Lim, S.; Kaai, S.C.; Quah, A.C.K.; Yan, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Quit Intentions among Adult Smokers in South Korea: Findings from the 2020 ITC Korea Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.O.; Fairhurst, S.K.; Velicer, W.F.; Velasquez, M.M.; Rossi, J.S. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.C.; Chan, S.S.; Ho, S.Y.; Fong, D.Y.; Lam, T.H. Predictors of intention to quit smoking in Hong Kong secondary school children. J. Public Health 2010, 32, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D.; McDonald, P.W.; Fong, G.T.; Borland, R. Do smokers know how to quit? Knowledge and perceived effectiveness of cessation assistance as predictors of cessation behaviour. Addiction 2004, 99, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Bangladesh Report 2009; World Health Organization, Country Office for Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, A.J.; Hirakata, V.N. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamhane, A.R.; Westfall, A.O.; Burkholder, G.A.; Cutter, G.R. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: Choice comes with consequences. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 5730–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.H.; Lee, M.; Zhuang, Y.L.; Gamst, A.; Wolfson, T. Interventions to increase smoking cessation at the population level: How much progress has been made in the last two decades? Tob. Control. 2012, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driezen, P.; Abdullah, A.S.; Quah, A.C.K.; Nargis, N.; Fong, G.T. Determinants of intentions to quit smoking among adult smokers in Bangladesh: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Bangladesh wave 2 survey. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2016, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Mahmood, M.A.; Spurrier, N.; Rahman, M.; Choudhury, S.R.; Leeder, S. Why do Bangladeshi people use smokeless tobacco products? Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP2197–NP2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huque, R.; Zaman, M.M.; Huq, S.M.; Sinha, D.N. Smokeless tobacco and public health in Bangladesh. Indian J. Public Health 2017, 61, S18–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naznin, E.; Wynne, O.; George, J.; Denham, A.M.J.; Hoque, M.E.; Milton, A.H.; Bonevski, B.; Stewart, K. Smokeless tobacco policy in Bangladesh: A stakeholder study of compatibility with the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2021, 40, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Jain, P.; Singh, P.K.; Reddy, K.S.; Bhargava, B. White paper on smokeless tobacco & women’s health in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 151, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Sultana, P.; Alam, J.; Akter, J.; Kundu, T.R. Pattern of Quitting Methods Used to Promote Tobacco Cessation in Bangladesh and Its Correlates. J. Biom. Biostat. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huque, R.; Al Azdi, Z.; Sheikh, A.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Mishu, M.P.; Mehrotra, R.; Ahmed, N.; Bauld, L.; Huq, S.M.; Alam, S.M.; et al. Policy priorities for strengthening smokeless tobacco control in Bangladesh: A mixed-methods analysis. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2021, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epperson, A.E.; Crouch, M.; Skan, J.; Benowitz, N.L.; Schnellbaecher, M.; Prochaska, J.J. Cultural and demographic correlates of dual tobacco use in a sample of Alaska Native adults who smoke cigarettes. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Convention Secretariat. 2014 Global Progress Report on Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Abdullah, A.S.; Driezen, P.; Quah, A.C.; Nargis, N.; Fong, G.T. Predictors of smoking cessation behavior among Bangladeshi adults: Findings from ITC Bangladesh survey. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2015, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.K.; Arora, M.; Gupta, V.K.; Reddy, K.S. Determinants of Tobacco Cessation Behaviour among Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in the States of Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh, India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 1931–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walton, K.; Wang, T.W.; Schauer, G.L.; Hu, S.; McGruder, H.F.; Jamal, A.; Babb, S. State-Specific Prevalence of Quit Attempts Among Adult Cigarette Smokers—United States, 2011–2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A.; Ghosh, P.; Paul, B.; Roy, S.; Ghose, S.; Yadav, A. Factors Associated with Intention and Attempt to Quit: A Study among Current Smokers in a Rural Community of West Bengal. Indian J. Community Med. 2021, 46, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, B.; Li, X.; Xie, R.; Li, W. Nicotine Dependence, Perceived Behavioral Control, Descriptive Quitting Norms, and Intentions to Quit Smoking among Chinese Male Regular Smokers. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Smoking | Smokeless Tobacco Use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2017 | 2009 | 2017 | |

| Current users, % | 23.0 | 18.0 | 27.2 | 20.6 |

| Age in years, % | ||||

| 15–24 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 25–44 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 11.6 | 8.2 |

| 45–64 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 9.9 | 7.9 |

| 65+ | 1.5 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Age first started using tobacco, mean | 18.5 | 18.3 | 26.6 | 28.4 |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Male | 22.2 | 17.6 | 13.1 | 7.9 |

| Female | 0.8 | 0.4 | 14.1 | 12.7 |

| Education, % | ||||

| No formal education | 11.1 | 6.9 | 15.1 | 11.0 |

| Less than Primary | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| Primary | 2.1 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.0 |

| Less than Secondary | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| Secondary or more | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Believe tobacco use is harmful for health, % | ||||

| Yes | 22.5 | 17.7 | 26.8 | 19.9 |

| No | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Wealth quintiles, % | ||||

| Lowest | 5.6 | 2.4 | 6.8 | 1.8 |

| Low | 6.1 | 3.4 | 7.0 | 3.8 |

| Middle | 4.7 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| High | 4.6 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| Highest | 2.0 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 5.5 |

| Profession, % | ||||

| Job (government/private) | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Business | 5.4 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 2.2 |

| Farming/Agricultural work | 8.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 2.6 |

| Labourer | 3.9 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Homemaker/Unemployed/other | 3.0 | 1.8 | 14.7 | 13.1 |

| Residence, % | ||||

| Urban | 5.6 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 3.7 |

| Rural | 17.4 | 13.6 | 21.3 | 16.9 |

| Quitting attempts among the current users during the 12 months prior to the survey, % | 45.3 | 43.4 | 26.9 | 29.9 |

| Current users intending to quit in the future, % | 68.0 | 66.0 | 48.7 | 51.2 |

| Variable | Quitting Attempts in Past 12 Months aPR (95% CI) n = 12,632 | Intention to Quit in Future aPR (95% CI) n = 12,577 |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco type | ||

| Smokeless (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Smoke | 1.38 (1.24–1.53) | 1.09 (1.02–1.16) |

| Both smoke and smokeless | 1.58 (1.41–1.77) § | 1.19 (1.11–1.28) § |

| User type | ||

| Occasional users (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Daily users | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) | 0.76 (0.71–0.82) |

| Received counselling, NRT, Quitline, or traditional treatment in the past 12 months | ||

| No (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.99 (2.86–3.12) | 1.41 (1.34–1.50) |

| Age | ||

| 15–24 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 25–44 | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) |

| 45–64 | 0.96 (0.83–1.10) | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) |

| 65+ | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 0.82 (0.74–0.92) |

| Sex | ||

| Male (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.62 (0.57–0.67) |

| Education | ||

| No formal education (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Less than Primary | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 1.04 (0.99–1.10) |

| Primary | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) |

| Less than Secondary | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) |

| Secondary or more | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) |

| Wealth quintiles | ||

| Lowest (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Low | 1.06 (0.96–1.18) | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) |

| Middle | 1.04 (0.93–1.15) | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) |

| High | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) |

| Highest | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 1.07 (0.99–1.14) |

| Profession | ||

| Job (government/private) (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Business | 1.04 (0.91–1.20) | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) |

| Farming/Agricultural work | 0.96 (0.83–1.10) | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) |

| Labourer | 0.89 (0.77–1.04) | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) |

| Homemaker/Unemployed/other | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) |

| Residence | ||

| Urban (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 0.94 (0.87–1.00) | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) |

| Age first started using tobacco daily | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) |

| Believe tobacco use is harmful to health | ||

| No (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.21 (0.94–1.56) | 1.21 (1.01–1.42) |

| Year | ||

| 2009 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 2017 | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 1.00 (0.95–1.04) |

| Variable | Intention to Quit Smoking aPR (95% CI) n = 6415 | Intention to Quit Smokeless Tobacco aPR (95% CI) n = 7320 |

|---|---|---|

| Attempted to quit in 12 months before the survey | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.45 (1.38–1.53) | 1.87 (1.76–1.98) |

| Tobacco type | ||

| Smokeless (ref) | - | 1 |

| Smoke (ref) | 1 | - |

| Both smoke and smokeless | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) |

| User type | ||

| Occasional users (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Daily users | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) | 0.80 (0.68–0.95) |

| Received counselling, NRT, Quitline or traditional treatment in the past 12 months | ||

| No (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.14 (1.08–1.20) | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) |

| Age | ||

| 15–24 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 25–44 | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) |

| 45–64 | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) |

| 65+ | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 0.67 (0.57–0.79) |

| Sex | ||

| Male (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.54 (0.40–0.73) | 0.61 (0.54–0.68) |

| Education | ||

| No formal education (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Less than Primary | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) |

| Primary | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) |

| Less than Secondary | 1.01 (0.93–1.08) | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) |

| Secondary or more | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 1.00 (0.89–1.14) |

| Wealth quintiles | ||

| Lowest (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Low | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) |

| Middle | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 1.14 (1.02–1.26) |

| High | 0.99 (0.92–1.08) | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) |

| Highest | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) |

| Profession | ||

| Job (government/private) (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Business | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) |

| Farming/Agricultural work | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 0.91 (0.79–1.06) |

| Labourer | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) |

| Homemaker/Unemployed/other | 1.10 (0.96–1.26) | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) |

| Residence | ||

| Urban (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) |

| Age first started using tobacco daily ∆ | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) |

| Believe tobacco use is harmful for health | ||

| No (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 1.18 (0.94–1.47) |

| Year | ||

| 2009 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.M. Comparison between Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in Their Past Attempts and Intentions to Quit: Analysis of Two Rounds of a National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013662

Islam MM. Comparison between Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in Their Past Attempts and Intentions to Quit: Analysis of Two Rounds of a National Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013662

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, M. Mofizul. 2022. "Comparison between Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in Their Past Attempts and Intentions to Quit: Analysis of Two Rounds of a National Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013662

APA StyleIslam, M. M. (2022). Comparison between Smokers and Smokeless Tobacco Users in Their Past Attempts and Intentions to Quit: Analysis of Two Rounds of a National Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013662