On the Quantum and Tempo of Women First Marriages in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The Total First Marriage Rate (TFMR)

2.2. The Tempo-Adjusted Period Proportion Ever Married (PPEM*)

2.3. Measuring Tempo Distortions and Decomposition Analysis

3. Data

4. Results

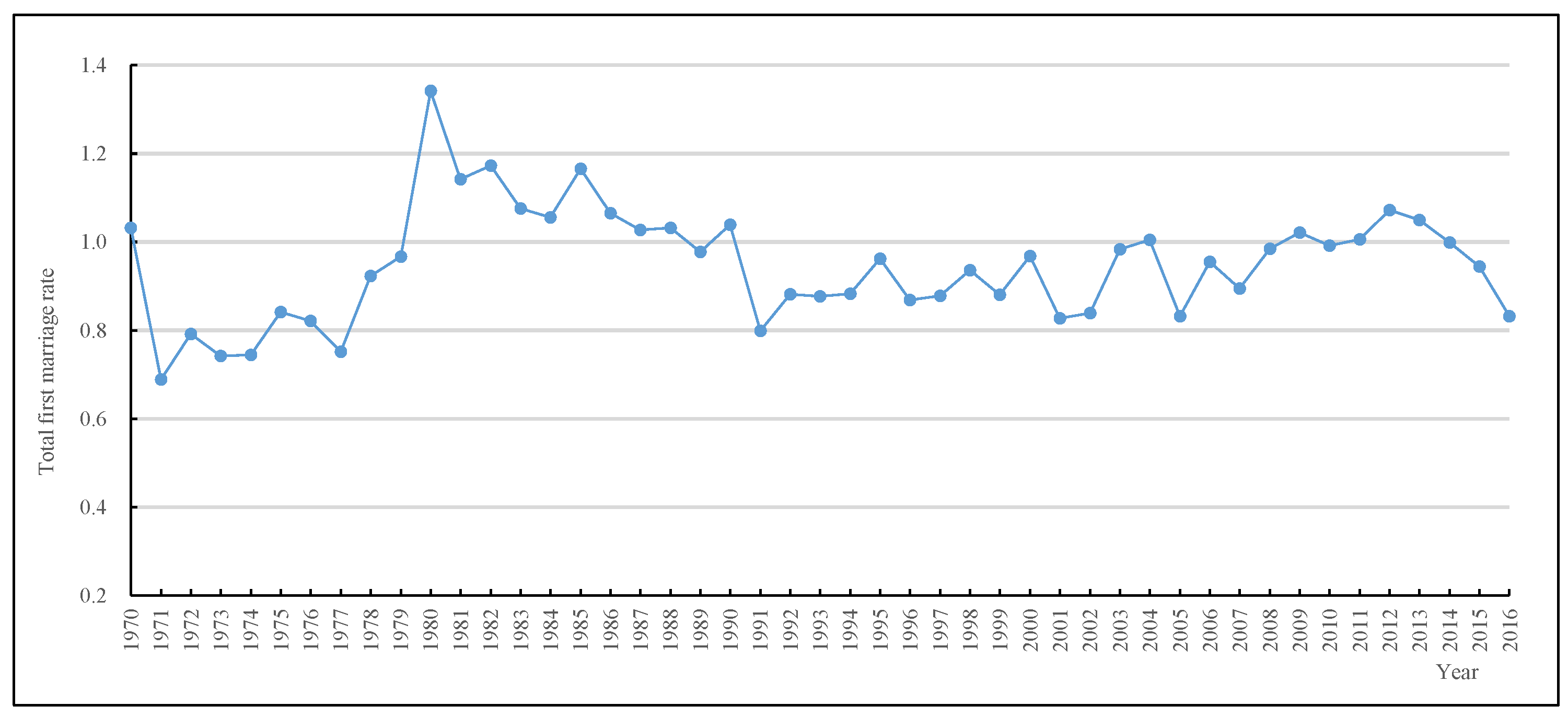

4.1. TFMR and PPEM* Trends, 1970–2016

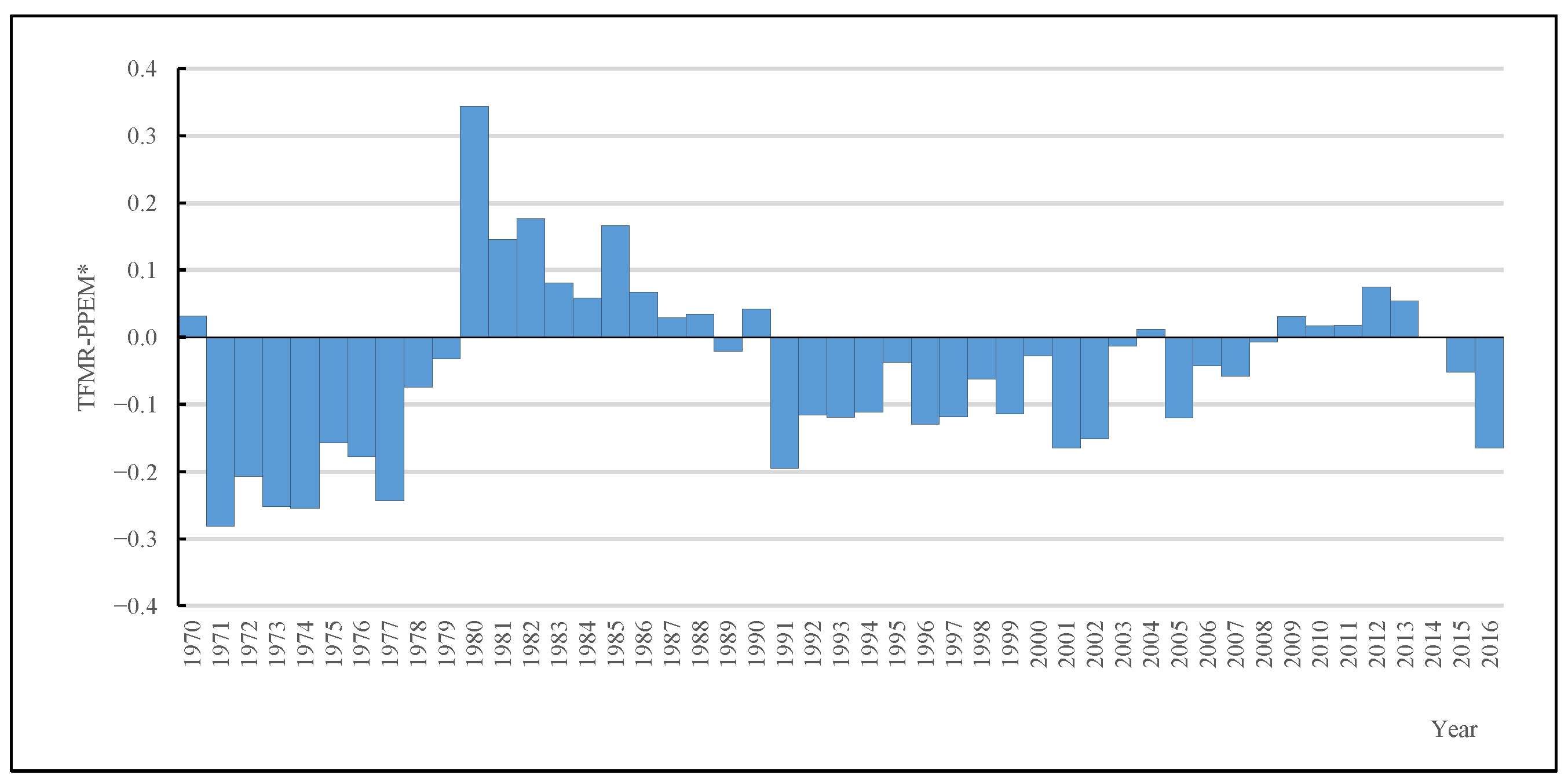

4.2. The Tempo Effects in TFMR of Chinese Women, 1970–2016

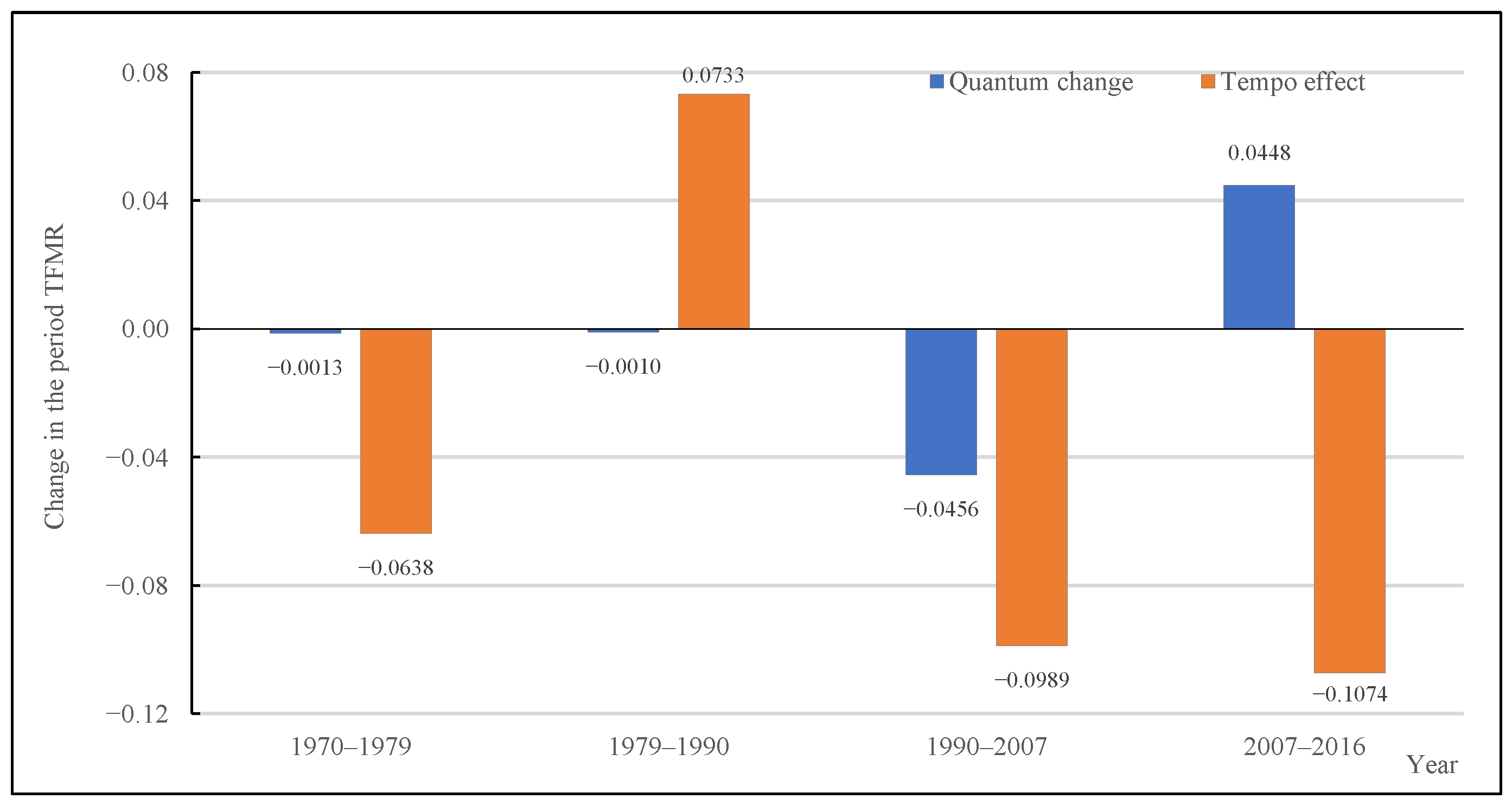

4.3. Decomposition of Changes in Period TFMR in Four Distinct Periods, 1970–2016

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, J.; Xie, Y. The Second Demographic Transition in China. Popul. Res. 2019, 43, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Zhao, X.H.; Xie, Y. Marriage and Divorce in China: Trends and Global Comparison. Popul. Res. 2020, 44, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, G.W.; Coale, A.J.; Stoto, M.A.; Trussell, T.J. A Reassessment of the Demography of Traditional Rural China. Popul. Index 1976, 42, 606–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coale, A.J.; Wang, F.; Riley, N.E.; De, L.F. Recent Trends in Fertility and Nuptiality in China. Science 1991, 251, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.E. Just How Do I love Thee? Marital Relations in Urban China. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.H.; Wang, X.F. Changing Patterns of Marriage and Divorce in Today’s China. In Analysing China’s Population; Attané, I., Gu, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J. Women’s Employment Rights in China: Creating Harmony for Women in The Workforce. Indiana J. Glob. Leg. Stud. 2010, 17, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. Delayed Marriage in China: The Influence of Social Forces and Individual Characteristics. In Proceedings of the Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–28 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Xie, Y. Changes in the Determinants of Marriage Entry in Post-reform Urban China. Demography 2015, 52, 1869–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldshuh, H. Gender, media, and myth-making: Constructing China’s Leftover Women. Asian J. Commun. 2018, 28, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, G.A. Fundamentals of Demographic Analysis: Concepts, Measures and Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Dong, S.; Jiang, Q.B. The Transformation of China’s First Marriage Pattern: Analysis on Nuptiality Table. Popul. Econ. 2013, 34, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.W. Changing Marriage Patterns in Asia. In Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series; National University of Singapore: Singapore, 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, W.J.J.; Hu, S. Coming of Age in Times of Change: The Transition to Adulthood in China. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2013, 646, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W. China’s ‘Later’ Marriage Policy and its Demographic Consequences. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 1992, 11, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, H.Y. Age at Marriage in the People’s Republic of China. China Q. 1983, 93, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coale, A.J. Marriage and Childbearing in China since 1940. Soc. Forces 1989, 67, 833–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Vaupel, J.W.; Wang, Z.L. Marriage and Fertility in China: 1950–1989. Genus 1993, 49, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, R. A Study on the Changes of Married Status of Chinese Women in the Past 40 Years. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 1993, 7, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Gu, B. Recent Changes in Marriage Patterns. In Transition and Challenge: China’s Population at the Beginning of the 21st Century; Zhao, Z., Guo, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 124–139. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. Trends in Educational Assortative Marriage in China from 1970 to 2000. Demogr. Res. 2010, 22, 733–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.W.; Liu, W. Are Chinese People Not Willing to Get Married? Study of Chinese Marriage from the Perspective of Cohort. Chin. J. Sociol. 2020, 35, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, W. China’s Low Fertility Trends: An Analysis Using Multiple Sources of Data. Popul. Econ. 2019, 40, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts, J.; Feeney, G. The Quantum and Tempo of Life-Cycle Events. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2006, 4, 115–151. [Google Scholar]

- Barbi, E.; Bongaarts, J.; Vaupel, J.W. (Eds.) How Long Do We Live? Demographic Models and Reflections on Tempo Effects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler-Dworak, M.; Engelhardt, H. On the Tempo and Quantum of First Marriages in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland: Changes in Mean Age and Variance. Demogr. Res. 2004, 10, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, R.; Canudas-Romo, V. Timing Effects on First Marriage: Twentieth-century Experience in England and Wales and the USA. Popul. Stud. 2005, 59, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Sánchez-Barricarte, J.J.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W. Marriage Squeeze in China’s Future. Asian Popul. Stud. 2011, 7, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J.; Feeney, G. On the Quantum and Tempo of Fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1998, 24, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J.; Sobotka, T. Demographic Explanations for the Recent Rise in European Fertility: Analysis Based on the Tempo and Parity-Adjusted Total Fertility. In European Demographic Research Papers; Vienna Institute of Demography: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts, J.; Sobotka, T. A Demographic Explanation for the Recent Rise in European Fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2012, 38, 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.H.; Sobotka, T. Ultra-low Fertility in South Korea: The Role of the Tempo Effect. Demogr. Res. 2018, 38, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.Q. Changing Patterns and Determinants of First Marriage over The History of the People’s Republic of China. Population 2019, 74, 205–235. [Google Scholar]

- Attané, I. Being a Woman in China Today: A Demography of Gender. China Perspect. 2012, 4, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yeung, W.J.J. Heterogeneity in Contemporary Chinese Marriage. J. Fam. Issues. 2014, 35, 1662–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Yeung, W.J.J. Marriage in Asia. J. Fam. Issues. 2014, 35, 1567–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T. Parametric Estimates on Age Patterns of First Marriage and Proportions of Never-marrying of Chinese Female. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2019, 33, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.B.; Yang, S.C.; Li, S.Z.; Feldman, M.W. The Decline in China’s Fertility Level:A Decomposition Analysis. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2019, 51, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Period | TFMR at the Start of the Period | TFMR at the End of the Period | Difference | Quantum | Tempo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–1979 | 1.0318 | 0.9667 | −0.0651 | −0.0013 | −0.0638 |

| (2.00%) | (98.00%) | ||||

| 1979–1990 | 0.9667 | 1.0390 | 0.0723 | −0.0010 | 0.0733 |

| (−1.38%) | (101.38%) | ||||

| 1990–2007 | 1.0390 | 0.8945 | −0.1445 | −0.0456 | −0.0989 |

| (31.56%) | (68.44%) | ||||

| 2007–2016 | 0.8945 | 0.8319 | −0.0626 | 0.0448 | −0.1074 |

| (−71.57%) | (171.57%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dan, J.; Zhu, N.; Mei, L. On the Quantum and Tempo of Women First Marriages in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013312

Dan J, Zhu N, Mei L. On the Quantum and Tempo of Women First Marriages in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013312

Chicago/Turabian StyleDan, Jingyi, Nong Zhu, and Li Mei. 2022. "On the Quantum and Tempo of Women First Marriages in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013312

APA StyleDan, J., Zhu, N., & Mei, L. (2022). On the Quantum and Tempo of Women First Marriages in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013312