How Social Determinants of Health of Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Long-Term Care Programs in Puerto Rico Influenced Recovery after Hurricane Maria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Theoretical Approach, Participants, and Recruitment

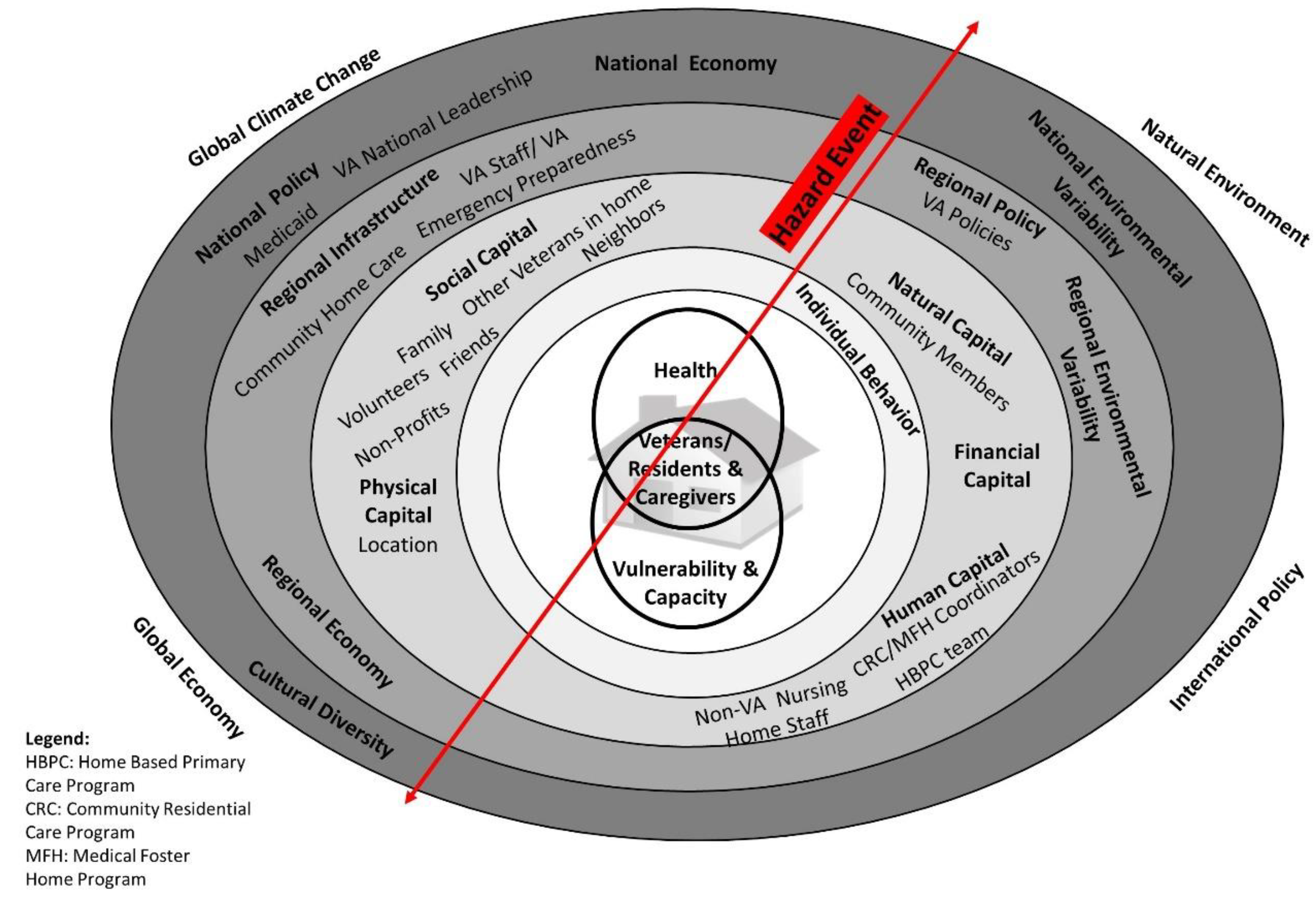

2.1.1. Study Design and Theoretical Approach

2.1.2. VA Home-Based Long-Term Care Settings

2.1.3. Participant Types

2.1.4. Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Economic Instability, Poverty, and Political Issues in Puerto Rico

“The big problem that we have as a country right now is the political problem. It’s the economy and all like, the loss that is the Gen X [speaking of young professionals leaving Puerto Rico for the mainland]. They [the U.S. government] don’t help us, you know? The economy, we could be better if we don’t have that problem…We are in a situation, that I was hearing in the news that it’s true. Like we don’t know if within the next year it’s going to be maybe worse [the economy].”(HBPC Dietician, 107)

“I’d see one patient and he would be like, ‘I live in Condado [busy, touristy neighborhood in San Juan]. And my cistern is broken. And I’m gonna get a new one.’ And we’d talk about that. And the next patient, would walk in and be like, “Yeah, I lost my new house. I’m living with my daughter” in some other very far campo [countryside] city or town. ‘And we don’t have water and we don’t have electricity.’ And, just the differences, from literally one patient leaving and the next coming in. We’re just like, ‘Okay, we’re all on the same island. You’re all veterans.’ And yeah, that was, that was really heartbreaking because, so many of them don’t live in affluent parts of Puerto Rico. Besides San Juan, Puerto Rico’s, it’s a lot of poverty. And, it’s seeing them and knowing...oh the most heartbreaking ones were when like the kids lived in the States, and you know, these people are like, 90 years old and living alone.”(VA Pharmacist, 158)

“I had patients whose families were in the United States. There was no communication. I didn’t have a [cell phone] signal. I’d go down to Caguas [town near her home] and there was signal... they must be worried about their family member and I can’t communicate with them. I couldn’t find the way until one day, being in line at Banco Popular, [the] phone started ringing. When I got home and heard all the messages from the families, I called them... they were calm, but they wanted to know, they wanted to be sure [the veterans were OK] and were willing to send whatever you needed. The families helped out a lot. They gave us money for gasoline. Their support was also there.”(CRC Caregiver, 137)

Interestingly, one HBPC staff member thought some of her veterans who were very poor would be struggling more after Maria, but because of their preparedness efforts and the strength of their communities, this was not the case. “I was surprised. Because, for example, [with] some humble, you know, like really poor patients that we have, I thought that we were going to be receiving lots of complaints, and they were managing the emergency so well”.(HBPC Occupational Therapist, 110)

3.2. Social Supports’ Role in Recovery

3.2.1. Strength of Communities and Reliance on Neighbors

“They would say, ‘Go to Kmart and purchase three tension wires of 100 or 250.’ And they would put them [lights] up from… all the way up there [pointing up high]… At night everyone had their lights on, but in the morning around 5 we had to disconnect it. I lasted about a month and a half with power from the streets, but in the day, I had to turn on the generator. So, I used to do the laundry at night. I would rinse off the urine off of their [her residents’] clothes and I would leave it there. At night I would put them in the washer and plugged it to the generator. But in the morning, we had to disconnect it. It was abusive because there was light everywhere else but in the houses [after they disconnected it]. At night you would pass somewhere and think that there was light, but the houses were in the dark. We had a very, very hard time.”(MFH Caregiver, 133)

“It was something that, even though we passed through that [tough situation] during the hurricane, in the middle of that battle we learned something from it, because we spent time with the neighbors. I knew to take them ice. I knew how to tell them… so I could give them some ice. You learn a lot from those things.”(MFH Caregiver, 114)

“They [neighbors] did all the jobs because… the government agencies were overwhelmed with work. So, they [neighbors] do a lot of the work. Even in my neighborhood… because we didn’t have any other assistance. So, most of the neighbors pick up the trees and all that stuff, so if there was an emergency, we can get out.”(HBPC Physician, 118)

“That is how it was done [the community working together]. Mainly in the countryside. In the countryside, if I want to get out of the house, and I have a tree trunk, well the community would go, and the ones that had a chain saw would go and cut down the tree trunk, so they could come out. Otherwise they couldn’t come out. They couldn’t wait for the government … they had to go out shopping and see what they could find.”(HBPC Nurse, 143)

“I had a lot of water. I had to donate water to other homes. Because they [local government] gave me a lot of water. I shared with other homes that were in a bit of a crisis. We didn’t communicate a lot, but we came together. I’d supply things that some didn’t have. After the hurricane, I had to donate to a home because they were not prepared.”(CRC Caregiver, 154)

“I think it just really speaks to how Puerto Ricans are as people. They’re just so loving and caring. And that was the number one feeling I felt after the storm, like everyone was just worried about everybody else and wanted to make sure people were okay, and reached out to strangers, and I think that was a really strong feeling afterwards..”(VA Pharmacist, 158)

“There was like this huge movement I would say, like a lot of people trying to help you show them a better connection. Just a lot of people that say ‘I make a lot of friends making the line for gas’… and like also the culture thing; like we talk a lot. We as Latinos we are more friendly… So that helped a lot because people try to help each other.”(HBPC Dietician, 107)

“I think that the reason that the people could survive this after [Maria]… was our neighbors. Just the people that were living here, got so much united to help. But in those first days, if it wasn’t for the, for us just to start opening roads. Or helping our neighbors, when you go, when you went to the houses everyone [said] “Well, my neighbor came, and she had a power generator and she gave me a line and I connected.” I saw a lot of that. I saw a lot of neighbors helping impaired elderly or people that have impairment or needed electricity. I have a, I had a very beautiful story of our patient that she [her neighbor] gave her the other line, so she could move the bed at night [to manually adjust a bed for a bedbound veteran]...a lot of Puerto Ricans giving food… water, that was very, very helpful for us.”(HBPC Physical Therapist, 108)

3.2.2. Working Together to Repair Electricity, Clear Roads

“Everything in the country was devastated. Especially [for] the people that weren’t aware of the warnings. They stayed where they were, and many were picked up along with their houses… Many people, they don’t listen to the warnings, they don’t even realize that their houses are not going to withstand the winds, the rain at that speed. They don’t understand. Some of us, we got together with our family and we got together in the best house to care for each other. The majority of people here, I don’t know if they were veterans or not, but it was deadly, terrible. The streets, the buildings, the people became sick. They had not been sick before, but they became depressed..”(Family member of CRC Veteran, 146)

Caregiver 1: “We had to take the initiative ... the neighbors sought out how we were to cooperate, we looked for people with understanding of electrical energy. Because with the generators, the gases, the noise. Economically speaking the generators… You couldn’t have them running 24 h because they could get damaged. I had to buy another generator to be able to use it.”

Caregiver 2: “One at night and one during the day. To be able to rotate them.”

Caregiver 1: “And they’d [veterans] want to watch their TV. And to keep them [veterans] distracted [post-Maria].”(CRC Caregivers, 137 and 138)

“It was because of people, neighbors, who were able to pick up those lines, I don’t even know how they did it. They brought them together, of course, they are expert electricians. But they don’t work with the electrical grid [i.e., with the power companies]. They knew that there were people being cared for here. They told me, ‘Don't worry. We are electrical experts; we are going to make it so the electricity [returns].’ So, they... that cable, they raised it and they gave us electricity.”(CRC Caregiver, 147).

“We organized and the day after the hurricane, around 1 in the afternoon, we all worked to clear the road…If I am in a situation and I need that road to be cleared, there is no other way; there is no other road that I can take. It’s a street with a dead end. Thanks to God, that day we all cleaned up because no one could go out. We are about 12 houses, we were stuck, we couldn’t go out. We all cleaned it up, we opened the road and were able to get through.”(CRC Son/Caregiver, 145)

“With Maria, the neighbors were out with their saws and the machetes to clear the trees. You had to get creative. Take the posts that were lying there and move them... until the road started clearing up. The neighbors worked together until the fourth day. [The] fifth day, the municipality came. One of the families knew the mayor, so the mayor sent the digger.”(CRC Caregiver, 154)

3.3. Mishandling of Recovery by Puerto Rico’s Government and the Federal Government

“I think [there’s] more trust between people. I think, not that Puerto Ricans don’t trust the federal government, but I think they’re more likely to trust their neighbors, and people they know, and I think FEMA also dropped the ball. And then people associated all federal help with just, a mess or false promises, or ‘It’s going to take forever’, or ‘They’re not gonna actually pay me what they said they’re gonna pay me’, or ‘They’re not gonna actually give me a roof’. I think there’s just so many, like, one thing after another kept falling through, and people were like, ‘Okay, well, I need to find some sort of other help, because this is not gonna work’.”(VA Pharmacist, 158)

Appreciation of Aid when It Did Arrive, Especially from Local Municipalities

“I have a story of one veteran who was living in a CRC foster home… that didn’t have power, but the caregiver had a power generator, and then the energy company here in Puerto Rico was doing some reparations in the community and the veteran was going to the people saying ‘Hey! I live in a foster home where all the residents are veterans!’ And there were some military staff with them [the electric company] and the military said, ‘Oh, you are a Veteran?’ ‘Yes, I am a Veteran and I live there, and we have been without power since many months ago’. And the military people make the connection with the emergency staff… and because of the military that foster home have power that day.”(Program Coordinator, 104)

“They [the VA] were always willing [to help] but obviously, no one could come all the way out here... But at least the local government was able to help more. They were more on top of things. For them [the Puerto Rico and federal governments], politics are always first, and these things are not... We did not see that help from the government. That commitment to help us without having to ask for it. We had to ask for help and they gave it to us within their ability. They’d help us, but not because it was born out of them [i.e., because they volunteered assistance]. Or because they knew there was a home here.”(CRC Caregiver, 138)

“We informed them, ‘You have to go… there is an office in every municipality that were working with that.’ And we just orient their relatives to go to that office, ask for them because we know every municipality have it. And some of them after we orient them, they went.”(HBPC Physician, 118)

“So, what do we do? We [the VA] do a really good job of knowing where our patients are, but we can’t get them supplies. They can’t go out and get water. They can’t go out and get to the grocery store. We have to do a better job of, once we identify where they are: Can they actually get supplies? And then us as the VA, connecting with the Red Cross or connecting with the community to be able to get them the resources that they need.”(VA National Leadership, 163)

“A lot of times, facilities will be like, ‘Oh, you’ve got a patient, we got to get their medications. Can you go deliver their medication?’ Well, the answer’s no. We don’t want our HBPC staff out during a storm. I mean, it’s just not safe. So, our role is really more to be able to communicate with the command centers, track our location and movements of our patients, what their needs are, and you know, really where they are, and how to get to them after the storm passes, and then track them. You know, after the storm passes and know where they are.”(VA Leadership, 163)

3.4. How Social Support Networks between Caregivers, Veterans, and Veterans’ Families Proved Critical to Health and Recovery

“Sometimes here in Puerto Rico, it’s pretty strong [i.e., common] to stay with the relatives at home and take [care of] them. It’s like, culturally [the] way to take care of elders. And sometimes they [older caregivers] postpone their health care needs and doesn’t place the veteran in a nursing home or long term care facility... And I say, ‘If you don’t take care of yourself, what will happen with the veteran, right? They will have to be placed in some, in some institutions… do your stuff now and then you can enjoy your time with veteran’.”(HBPC Physician, 118)

“It is very important that our patients have recreational time. To be able to get out and do something different. We have outings, visits to the beach. Simple things. My mother sometimes will start a barbecue and makes them burgers as if we were at the beach but in the home. They have a nice time, singing. We put on music, the microphone. And we spend the day in our residence.”(CRC Son/Caregiver, 145)

“I had three employees [caregiving staff] who lost everything. The only thing left was the ground. So, what I did was tell them, ‘You can stay here.’ They didn’t have food... They didn’t all prepare at home, so there was no food [at their homes]. They didn’t have gas… There was no way of purchasing; whoever had not managed to purchase a gas stove, a gas tank, by then you couldn’t get one. People could not cook. Employees ate here. But at that time cooking was done for everyone... We united. I told them, ‘You can come at a certain time.’ And I’d give them food.(CRC Owner/Caregiver 153)

“There are families that perhaps are not very close to them [the veterans], but as a home we try to promote closeness. We at times seek ways for them to be involved with them [Veterans]. We try to create a habit in them to come. We’ll ask for something for them, but it is just an excuse to get them to come here to see them.”(CRC Caregiver, 138)

3.5. VA Staff Working Together Assisted in Recovery

“Other coworkers. The help from amongst us. We helped each other so we wouldn’t go around alone. If something should happen while in the car, there were no phones. If we had a flat tire, there was no way to get around that. What helped us the most was the support that we had for each other. We’d never go out alone, we always [were] with somebody else.”(HBPC Nurse, 143)

“The immense work they [the caregivers] did [before, during, and after Maria]. They maintained the same quality of life for our Veterans; the same as before. They maintained that same quality… We danced, and we had a Christmas party. It is a way to forget and to distract them from that adversity of that situation, that anxiety of not having electricity.”(CRC Social Worker, 157)

“I think the most important thing is the contact with the patient or family member, be it via phone or if you can, visit the home. Visiting is so important because this culture likes that, for it to be face-to-face, to see the professional. And to educate the patient in person. They are very grateful when we visit the home and continue to track the patient in whatever they need in that moment. Be it foot care, blood pressure, diabetes, high blood glucose, whatever their condition may be, they prefer that continued care is provided by visiting the home. That is what I think is the most important.”(HBPC Nurse, 143)

“I feel like it’s kind of part of the culture here… like whenever they come in and they have appointments, it’s like it’s like a party. We talk to the daughter and then you hear about the granddaughter… I just feel like that [the] culture down here is very, like open and talkative and inclusive. So, but yes… everyone would want to tell their stories [post-Maria]. So, like, “’This is my experience. This is what happened. This is where I was. This was who was with me.’ And then also, their concern for us [VA staff] was, like, very something that really shocked me. Like here they are, these patients who had like, lost everything. And they’re like, ‘But where were you? Donde estaste aqui?’ [during Maria]… That was something that really stuck out to me. Like just how much they cared about us, was like, really touching.”(VA Pharmacist, 158)

“I sometimes think we need another hurricane to see if we can become even more sensitive. Because we were more sensitive for some time. You’d see everyone, very friendly. Everyone cooperating. I miss that. I miss that brotherhood that once the power and water returned, we are no longer a collective, we are individuals, we live on the individual level. The veterans of course have always had that. They treat each other like family.”(CRC Social Worker, 157)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Díaz, C.E. Maria in Puerto Rico: Natural disaster in a colonial archipelago. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, L.; Lebrón, M.; Chase, M. Eye of the Storm. NACLA Rep. Am. 2018, 50, 109–111. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10714839.2018.1479417 (accessed on 1 January 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abbasi, J. Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico: A Physician Looks Back at the Storm. JAMA 2018, 320, 629. Available online: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2018.8244 (accessed on 16 January 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtveld, M. Disasters through the Lens of Disparities: Elevate Community Resilience as an Essential Public Health Service. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 28–30. Available online: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304193 (accessed on 22 May 2018). [CrossRef]

- Lloréns, H. Ruin nation. NACLA Rep. Am. 2018, 50, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, D.A. Response and Recovery after Maria: Lessons for Disaster Law and Policy. Rev. Jurid. UPR Disaster Law Policy 2018, 87, 743–771. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/936195d5 (accessed on 22 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- 8 Questions & Answers about Puerto Rico the Kaiser Commision on Medicaid and the Uninsured. 2016 [cited 10 January 2018]. p. 1–10. Available online: https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/8-questions-and-answers-about-puerto-rico/ (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- Matos-Moreno, A.; Verdery, A.M.; Mendes de Leon, C.F.; De Jesús-Monge, V.M.; Santos-Lozada, A.R. Aging and the Left Behind: Puerto Rico and Its Unconventional Rapid Aging. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 964–973. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/62/7/964/6607773 (accessed on 30 August 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico U.S. In Census Bureau. 2017 [cited 15 July 2018]. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/pr/PST045217 (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Ruiter, M.C.; Couasnon, A.; Homberg, M.J.C.; Daniell, J.E.; Gill, J.C.; Ward, P.J. Why We Can No Longer Ignore Consecutive Disasters. Earth’s Futur. 2020, 8, e2019EF001425. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2019EF001425 (accessed on 30 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Goodwin Veenema, T.; Rush, Z.; Depriest, K.; Mccauley, L. Climate change-related hurricane impact on Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, environment risk reduction, and the social determinants of health. Nurs Econ. 2019, 37, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla, C.D. Perspective: The View from Puerto Rico—Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1801–1803. Available online: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:New+engla+nd+journal#0 (accessed on 22 May 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandlyn, J.; Thomas, D.S.K.; Brett, J. Theoretical Framing of Worldviews, Values, and Structural Dimensions of Disasters. In Social Vulnerability to Disasters, 2nd ed.; Thomas, D.S.K., Phillips, B.D., Lovekamp, W.E., Fothergill, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, C.; Ailshire, J.A. Aging in Puerto Rico: A Comparison of Health Status among Island Puerto Rican and Mainland, U.S. Older Adults. J. Aging Health 2017, 29, 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, P.S.; Shively, G.E. Disaster Risk, Social Vulnerability, and Economic Development. Disasters 2017, 41, 324–351. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/disa.12199 (accessed on 22 May 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, K.; Lallemand, N.; Napoles, A.; Zuckerman, S. Environmental Scan of Puerto Rico’s Health Care Infrastructure 2017. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/87016/2001051-environmental-scan-of-puerto-ricos-health-care-infrastructure_1.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2018).

- Wentzell, S. Through Hurricanes, VA Continues Efforts to Care for Veterans VAntage Point: Official Blog of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2017 [cited 30 April 2018]. Available online: https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/41864/through-hurricanes-va-continues-efforts-to-care-for-veterans/ (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HHS, FEMA, DOD and VA Continue to Provide Sustained and Critical Medical Care Support for Puerto Rico as Part of Trump Administration Response to Hurricane Maria. 2017 [cited 1 December 2017]. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/12/hhs-fema-dod-and-va-continue-provide-sustained-and-critical-medical-care.html (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Lane, S.J.; McGrady, E. Nursing Home Self-assessment of Implementation of Emergency Preparedness Standards. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2016, 31, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, S.; Parsons, A.J.Q.; Hirabayashi, M.; Kinoshita, R.; Liao, Y.; Hodgson, S. Social determinants of mid- to long-term disaster impacts on health: A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed; Sage Publications: Thosand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.S.K.; Scandlyn, J.; Brett, J.; Oviatt, K. Model of factors contributing to vulnerability and health. In Social Vulnerability to Disasters, 2nd ed.; Thomas, D.S.K., Phillips, B.D., Lovekamp, W.E., Fothergill, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.E., Ed.; Grenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Haverhals, L.M.; Manheim, C.E.; Jones, J.; Levy, C. Launching Medical Foster Home programs: Key components to growing this alternative to nursing home placement. J. Hous. Elderly 2017, 31, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colello, K.J.; Viranga Panangala, S. Long-Term Care Services for Veterans Congressional Research Service. 2017 [cited 15 January 2018]. pp. 1–37. Available online: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44697.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Karuza, J.; Gillespie, S.M.; Olsan, T.; Cai, X.; Dang, S.; Intrator, O.; Li, J.; Gao, S.; Kinosian, B.; Edes, T. National Structural Survey of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Primary Care Programs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2697–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverhals, L.M.; Manheim, C.; Gilman, C.; Karuza, J.; Olsan, T.; Edwards, S.T.; Levy, C.R.; Gillespie, S.M. Dedicated to the mission: Strategies US Department of Veterans Affairs home-based primary care teams apply to keep veterans at home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2511–2518. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jgs.16171 (accessed on 11 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 159–176. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244014522633 (accessed on 24 March 2018). [CrossRef]

- Small, M.L. ‘How Many Cases do I Need?’: On Science and the Logic of Case Selection in Field-Based Research. Ethnography 2009, 10, 5–38. Available online: http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/1466138108099586 (accessed on 4 December 2014). [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.T. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, G.; Young, J. Beyond Open-Ended Questions: Purposeful Interview Guide Development to Elicit Rich, Trustworthy Data Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) Demonstration Labs. 2018 [cited 15 June 2018]. Available online: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=2439 (accessed on 17 December 2017).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas.ti Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2020. Available online: https://atlasti.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Morse, J.M. “Perfectly Healthy, But Dead”: The Myth of Inter-Rater Reliability. Qual. Health Res. 1997, 7, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marrero, T.; Castro-Rivera, A. Let’s Not Forget About Non-Land-Falling Cyclones: Tendencies and Impacts in Puerto Rico. Nat. Hazards 2019, 98, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cange, C.; McGaw-Césaire, J. Long-Term Public Health Responses in High-Impact Weather Events: Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico as a Case Study. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 14, 18–22. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=629752218 (accessed on 11 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kishore, N.; Mareques, D.; Mahmud, A.; Kiang, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Fuller, A.; Ebner, P.; Sorensen, C.; Racy, F.; Lemerry, J. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, pp. 162–170. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Social Determinants of Health U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022 [cited 10 June 2022]. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Benach, J.; Díaz, M.R.; Muñoz, N.J.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Pericàs, J.M. What the Puerto Rican Hurricanes Make Visible: Chronicle of a Public Health Disaster Foretold. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudner, N. Disaster Care and Socioeconomic Vulnerability in Puerto Rico. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2019, 30, 495–501. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/724519 (accessed on 11 January 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, M.T.; Dávila, A.; Rodríguez, H. Migration, geographic destinations, and socioeconomic outcomes of puerto ricans during la crisis boricua: Implications for island and stateside communities post-Maria. Cent. J. 2018, 30, 208–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Arrigoitia, M. Editorial: Revolt, Chronic Disaster and Hope. City 2019, 23, 405–410. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13604813.2019.1700657 (accessed on 11 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sledge, D.; Thomas, H.F. From disaster response to community recovery: Nongovernmental entities, government, and public health. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romo, V.; Booker, B. Puerto Rico Relief: Trump Declares Major Disaster after Series of Earthquakes National Public Radio. 2020 [cited 21 January 2020]. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/01/16/797168084/puerto-rico-relief-trump-declares-major-disaster-after-series-of-earthquakes (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Sou, G.; Webber, R. Disruption and recovery of intangible resources during environmental crises: Longitudinal research on ‘home’ in post-disaster Puerto Rico. Geoforum 2019, 106, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSorley, A.-M.M. Hurricane Fiona Exposes More Than Crumbling Infrastructure in Puerto Rico Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice, & Health. 2022 [cited 7 October 2022]. Available online: https://www.racialhealthequity.org/blog/annamichellmcsorley/puertorico/hurricanefiona (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Aldrich, D.P. The power of people: Social capital’s role in recovery from the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Nat. Hazards. 2011, 56, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.A. Elderly perceptions of social capital and age-related disaster vulnerability. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uekusa, S. Rethinking Resilience: Bourdieu’s Contribution to Disaster Research. Resilience 2017, 3293, 181–195. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21693293.2017.1308635 (accessed on 20 June 2018). [CrossRef]

- Project Report: Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico Washington, DC. 2018. Available online: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/projects/PRstudy/AcertainmentoftheEstimatedExcessMortalityfromHurricaneMariainPuertoRico.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Phibbs, S.; Kenney, C.; Rivera-Munoz, G.; Huggins, T.J.; Severinsen, C.; Curtis, B. The inverse response law: Theory and relevance to the aftermath of disasters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramutti, C.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Vos, S.R.; Schwartz, S.J. The mental health impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. Working with families displaced by Hurricane Maria. Soc. Work Groups 2019, 43, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, J.; Tamez, M.; Ríos-Bedoya, C.F.; Xiao, R.S.; Tucker, K.L.; Rodríguez-Orengo, J.F. Health Conditions and Lifestyle Risk Factors of Adults Living in Puerto Rico: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 491. Available online: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5359-z (accessed on 11 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, E.; Hinojosa, J. Estimates of Post-Hurricane María Exodus from Puerto Rico. Research Brief. Cent Puerto Rico. Stud. 2017, (October 2017), 1–7. Available online: http://sp.rcm.upr.eduj (accessed on 29 September 2019).

| VA Medical Foster Home (MFH) | VA Community Residential Care (CRC) | VA Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description of Long-Term Care Program (oversight, type of caregiver) | Up to three veterans/residents live in the private home of a non-VA caregiver, who is recruited and screened by the VA | Size can vary from small, family-sized homes to larger facilities. Can house larger number of veterans. Facilities are inspected and approved by the VA. Veterans have no family or caregiver of their own and receive daily care from CRC caregivers who are non-VA employees | Veterans usually live in their own homes, usually with a familial caregiver, or they have a caregiver who lives nearby, or veteran lives alone. Veterans are enrolled into HBPC program by the VA |

| Description of care provided/care needs | MFHs are a type of CRC, usually with more medically complex veterans than CRCs. Veterans receive care from HBPC interdisciplinary teams | Veterans often have mental health care/psychiatric care and medical needs. While intended for less medically complex veterans, many in CRCs are also wheelchair-bound and need more advanced care. Veterans go to the VA for medical care | Veterans receive longitudinal care in-home from VA HBPC interdisciplinary teams who partner with the veterans’ caregiver(s) (if veteran has a caregiver) to provide care |

| Type of Participant | Number |

|---|---|

| VA MFH/CRC Caregivers | 10 |

| VA Staff | 15 |

| Family Members of VA Caregivers | 2 |

| Family member of Veteran | 1 |

| VA MFH Veterans | 4 |

| VA CRC Veterans | 8 |

| VA National Leadership | 4 |

| TOTAL | 44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haverhals, L.M. How Social Determinants of Health of Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Long-Term Care Programs in Puerto Rico Influenced Recovery after Hurricane Maria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013243

Haverhals LM. How Social Determinants of Health of Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Long-Term Care Programs in Puerto Rico Influenced Recovery after Hurricane Maria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013243

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaverhals, Leah M. 2022. "How Social Determinants of Health of Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Long-Term Care Programs in Puerto Rico Influenced Recovery after Hurricane Maria" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013243

APA StyleHaverhals, L. M. (2022). How Social Determinants of Health of Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Home-Based Long-Term Care Programs in Puerto Rico Influenced Recovery after Hurricane Maria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013243