The Impact of Internet Use on the Happiness of Chinese Civil Servants: A Mediation Analysis Based on Self-Rated Health

Abstract

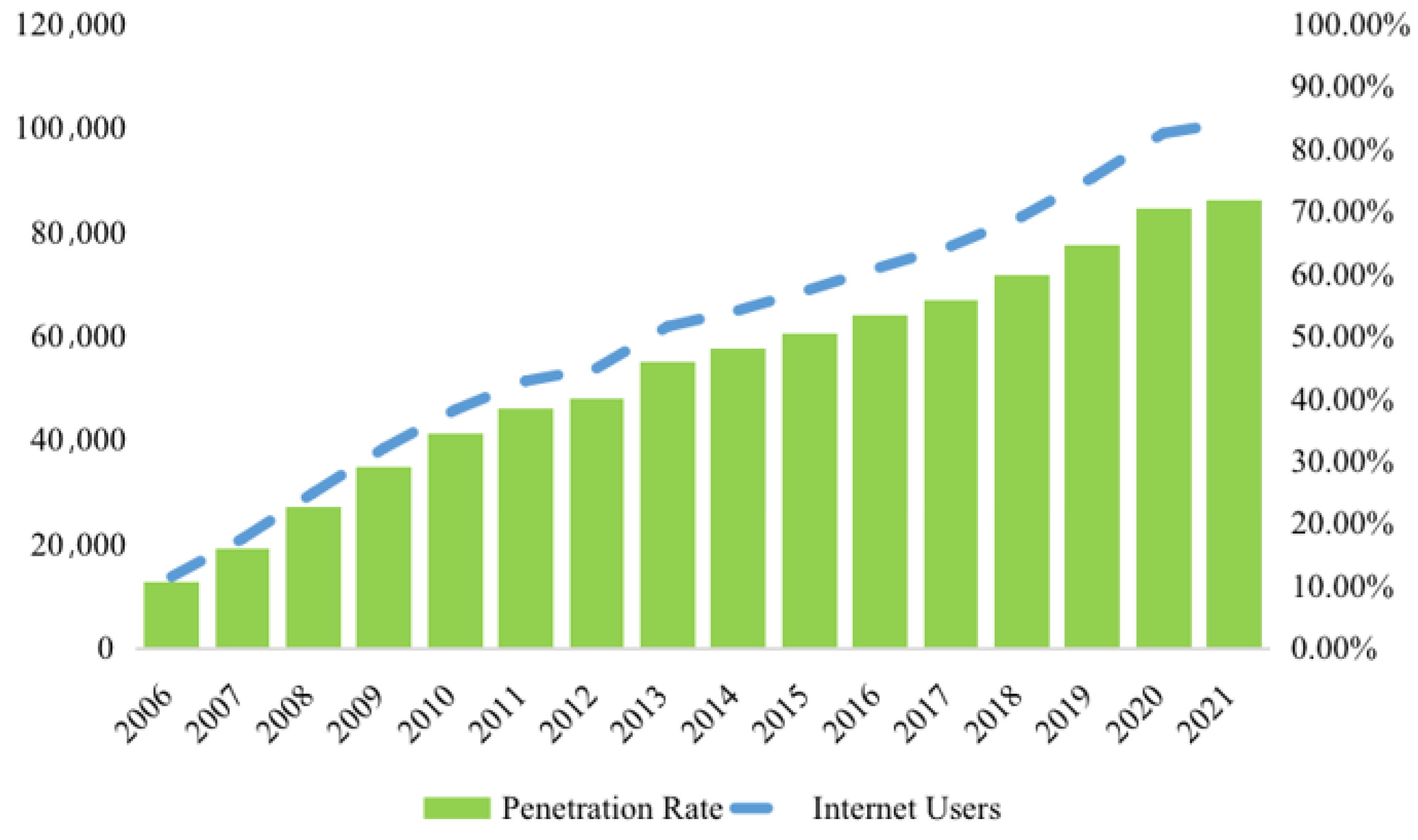

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Design

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis Strategies

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Robustness Test

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

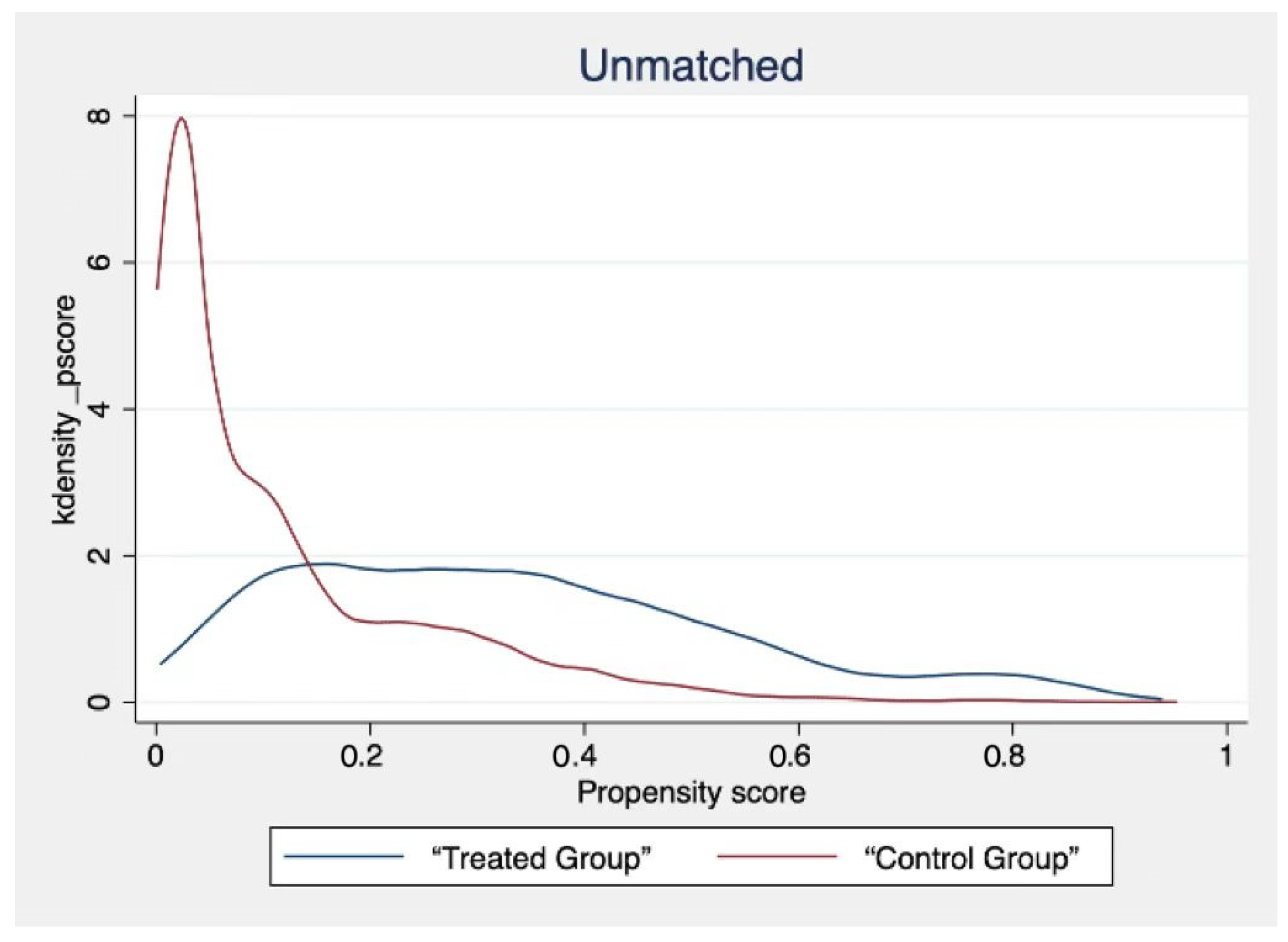

4.4. PSM Model Eliminates Sample Selectivity Bias

4.5. Internet Use and Civil Servants’ Well-Being: A Health Mediation Analysis

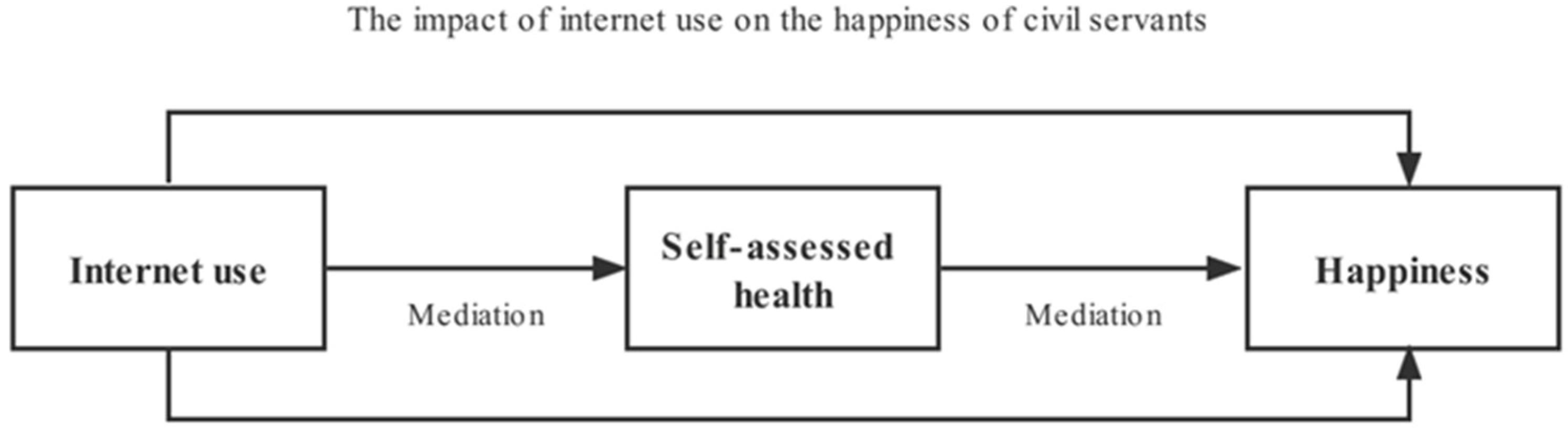

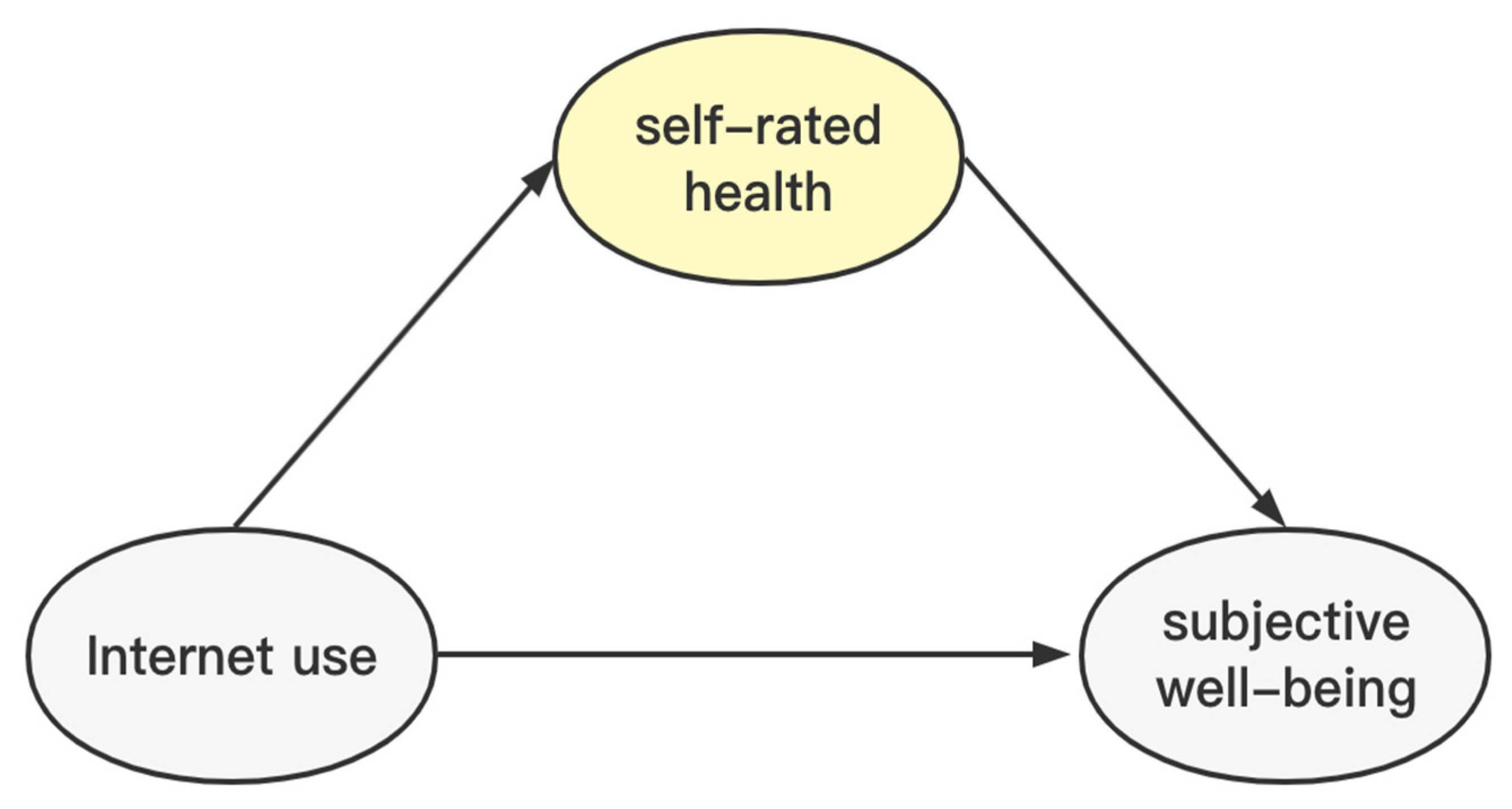

- To examine the effect of Internet use on the well-being of civil servants:

- Examining the impact of Internet use on the health of civil servants:

- Incorporating Internet use and health variables into the model simultaneously:where is the control variable and denotes the mediating variable. If the coefficient of Equation (4) is significant in the first step of the estimation results, it indicates that Internet use has a significant effect on civil servants’ happiness and allows for the continuation of the testing. Next, if the coefficient of Equation (5) is significant in the second step, it indicates that Internet use has a significant effect on the mediating variable health and allows for the third test to be conducted. In the last test step, health is added as a variable and, if the coefficient of the mediating variable in Equation (6) is significant and the Internet use variable is also significant, it indicates that there is a partial mediating effect of health between Internet use and civil servants’ happiness. However, if the coefficient of the mediating variable is significant and the Internet use variable is not significant, it indicates a full mediating effect (Table 8).

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Finding

5.2. Policy Implication

5.3. Research Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X. The relationship between work pressure, job satisfaction and turnover intention of local tax civil servants: The moderating role of psychological capital. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 23, 326–329, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Chen, Y. The effect of mission valence on the job well-being of grass-roots civil servants: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of public service motivation. Public Adm. Policy Rev. 2022, 11, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. The impact of Internet use on well-being: An empirical study based on urban micro-data. Soft Sci. 2014, 28, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Dai, S. Platform strategy and platform media construction in the “Internet+” era. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fu, L.; Li, T.; Sun, B. Research on the internet and digital economy based on China’s practice—A summary of the first internet and digital economy forum. Econ. Res. 2019, 54, 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Hu, X.; Feng, Y. Internet application and entrepreneurial performance: The mediating role of social capital. Tech. Econ. 2017, 36, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Yue, Z. A study on the influence of Internet use on the well-being of rural residents. Res. World 2019, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Sun, P. Does internet use improve residents’ well-being—A validation based on household microdata. Nankai Econ. Res. 2017, 3, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The grassroots bureaucracy and the dilemma of policy implementation—A review of the grassroots bureaucracy: The dilemma of public officials. Public Adm. Policy Rev. 2017, 6, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. The Science of Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Senik, C. Income Distribution and Subjective Happiness: A Survey; OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri-Carbonell, A. Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M.A. Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yao, W. The relationship between migrant workers’ income and subjective well-being: The role of social support and personality. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 37, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R.J.; Oswald, A.J. Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfers, J. Is business cycle volatility costly? Evidence from surveys of subjective well-being. Int. Financ. 2003, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann-Steffen, I.; Vatter, A. Does satisfaction with democracy really increase happiness? Direct democracy and individual satisfaction in Switzerland. Political Behav. 2012, 34, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Plum, T. How can the government make people happy?—An empirical study on the influence of government quality on residents’ happiness. Manag. World 2012, 8, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: Americans’ Perceptions of Life Quality; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, F.; Clinch, J.P.; Ferreira, S. Happiness, geography and the environment. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrant, G.; Kolev, A.; Tassot, C. The Pursuit of Happiness: Does Gender Parity in Social Institutions Matter? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.A. Happiness and Age Cycles-Return to Start…?: On the Functional Relationship between Subjective Well-Being and Age; OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, S.; Bowden, A.; Bloomfield, J.; Jose, B.; Wilson, V. Caring for the carers in a public health district: A well-being initiative to support healthcare professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3701–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Wu, Y.; Chang, S.; Wang, L. Associations between occupational stress, burnout and well-being among manufacturing workers: Mediating roles of psychological capital and self-esteem. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Income, health and subjective well-being. Econ. Issues 2017, 11, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.F.; Juvonen, J.; Gable, S.L. Internet use and well-being in adolescence. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; Gregor, P. Computer use has no demonstrated impact on the well-being of older adults. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Leng, C. Influence of internet use on residents’ well-being: Empirical evidence from CSS2013. Econ. Rev. 2018, 1, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasserre, F. Logistics and the Internet: Transportation and location issues are crucial in the logistics chain. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zou, C.; Liu, H. Research on internet financial model. New Financ. Rev. 2012, 12, 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass, A. An assessment of consumers product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2000, 21, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, Z.; Chen, B. Technology and culture: How the internet changes personal values? Econ. Dyn. 2016, 4, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cilesiz, S. Educational computer use in leisure contexts: A phenomenological study of adolescents’ experiences at Internet cafes. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 46, 232–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. Legal regulation of internet finance—Based on the perspective of information tools. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 107–126, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, L.H.; Gant, L.M. In defense of the Internet: The relationship between Internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2004, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuihong, L.; Chengzhi, Y. The impact of Internet use on residents’ subjective well-being: An empirical analysis based on national data. Soc. Sci. China 2019, 40, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Kiesler, S.; Boneva, B.; Cummings, J.; Helgeson, V.; Crawford, A. Internet paradox revisited. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Burke, M. Internet use and psychological well-being: Effects of activity and audience. Commun. ACM 2015, 58, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M. Trends in the use of the Internet for health purposes in Poland. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, N.; Saperstein, S.; Pleis, J. Using the internet for health-related activities: Findings from a national probability sample. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009, 11, e1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.E.; Renson, A.; Zivich, P. Social media-and internet-based disease surveillance for public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, T.; Wang, H. Does internet use affect levels of depression among older adults in China? A propensity score matching approach. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z. The impact of internet use on the health of the elderly. Chin. J. Pop. Sci. 2020, 14–26, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Farkiya, R.; Tiwari, D.; Modi, N.C. A study on impact of internet usage on quality of life of senior citizens. Jaipurian Int. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 4, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhou, W. Influence mechanism and heterogeneity of Internet use on the health status of the elderly in China. Demogr. J. 2022, 44, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, C. Effects of mobile internet application (APP) use on physical and mental health of older adults: The use of WeChat, WeChat friend circle and mobile payment as examples. Pop Dev. 2021, 27, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Ding, H. The relationship between internet use and population health: A cross-sectional survey in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ding, H.; Li, Z. Does internet use impact the health status of middle-aged and older populations? Evidence from China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, W. Associations between mobile internet use and self-rated and mental health of the Chinese population: Evidence from China family panel studies 2020. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Park, S.; Cha, S. Relationships of mental health and internet use in Korean adolescents. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, K.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z. Internet, life time allocation and physical health of rural adolescents. Nankai Econ. Res. 2019, 4, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layard, R. Measuring subjective well-being. Science 2010, 327, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, A.T.; Morrison, M.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. Subjective well-being around the world: Trends and predictors across the life span. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16489–16493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.C. Social indicators research and health-related quality of life research. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 65, 27–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, C.; Zhu, Z. A study of the effect of the Internet on the well-being of rural residents. South. Econ. 2018, 8, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analysis of mediating effects: Methodology and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, Y. Chinese middle-aged and older adults’ Internet use and happiness: The mediating roles of loneliness and social engagement. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Allen, J.; Stephens, C.; Alpass, F. Longitudinal analysis of the relationship between purposes of internet use and well-being among older adults. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavera, C.; Usán, P. Relationship between social skills and happiness: Differences by gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Internet use, leisure preferences and happiness of rural residents—An analysis based on a gender difference perspective. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. 2018, 4, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Liu, Z. Internet use, class identity and happiness of rural residents. China’s Rural Econ. 2022, 8, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Digital divide or information welfare: The impact of internet use on residents’ subjective welfare. Econ. Dyn. 2020, 2, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, C. A study on the impact of insurance participation on the well-being of Chinese residents: An analysis of the mediating effect based on health. J. Sichuan Univ. Light Chem. Ind. 2020, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez-Fernández, M.A.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. Pathways from emotional intelligence to well-being and health outcomes among unemployed: Mediation by health-promoting behaviours. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Variable Definition | OB | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Civil Service Happiness | 1–5, the higher the score, the higher the happiness | 3793 | 3.541 | 0.957 |

| Independent Variable | ||||

| Internet Usage | No = 0, Yes = 1 | 3793 | 0.936 | 0.244 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Gender | Female = 0, Male = 1 | 3793 | 0.366 | 0.482 |

| Age | Continuous Variable (years) | 3793 | 32.644 | 5.995 |

| Marital Status | Unmarried = 1, Married = 2, Divorced = 3 | 3793 | 1.858 | 0.578 |

| Education Level | College and below = 1, Bachelor = 2, Master = 3, Doctor = 4 | 3793 | 2.443 | 0.679 |

| Job Income | Continuous Variables. | 3793 | 50,294.53 | 46,293.55 |

| Smoking History | No = 0, Yes = 1 | 3793 | 0.086 | 0.280 |

| Drinking History | No = 0, Yes = 1 | 3793 | 0.057 | 0.232 |

| Variable | VIF |

|---|---|

| Gender | 1.56 |

| Age | 1.83 |

| Marital Status | 1.72 |

| Education Level | 1.34 |

| Job Income | 1.66 |

| Smoking History | 1.52 |

| Self-assessment of Health | 1.28 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | Happiness | Happiness | |

| Internet Usage | 0.085 *** (0.035) | 0.050 *** (0.041) | 0.045 *** (0.042) |

| Gender | −0.011 ** (0.036) | −0.010 ** (0.041) | |

| Age | 0.001 (0.008) | 0.001 (0.003) | |

| Marital Status | −0.008 ** (0.033) | −0.009 ** (0.033) | |

| Education Level | 0056 ** (0.031) | 0.050 ** (0.032) | |

| Job Income | 0.000 (0.000) | ||

| Smoking History | −0.128 * (0.066) | ||

| Drinking History | 0.019 (0.077) | ||

| Sample Size | 3793 | 3793 | 3793 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.0006 | 0.0009 | 0.0014 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | Happiness | Happiness | |

| Internet Usage | 0.097 *** (0.031) | 0.053 *** (0.041) | 0.046 *** (0.042) |

| Gender | −0.016 ** (0.033) | −0.010 ** (0.041) | |

| Age | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | |

| Marital Status | −0.007 ** (0.030) | −0.007 ** (0.029) | |

| Education Level | 0069 ** (0.028) | 0.061 ** (0.029) | |

| Job Income | 0.000 (0.000) | ||

| Smoking History | −0.118 ** (0.060) | ||

| Drinking History | 0.010 (0.070) | ||

| Sample Size | 3793 | 3793 | 3793 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Variables | Education Level | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate and Below | Master’s and Above | Women | Male | |

| Civil Service Happiness | Civil Service Happiness | |||

| Internet Use | 0.070 ** (0.038) | 0.617 * (0.369) | 0.047 * (0.052) | 0.053 * (0.071) |

| Control Variables | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Adj-R2 | 0.0011 | 0.0382 | 0.0044 | 0.0033 |

| Variables | Unmatched Matched | Mean | Bias (%) | Reduce Bias (%) | t-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | t-Value | p > |t| | ||||

| Gender | Unmatched | 0.258 | 0.183 | 28.6 | 98.3 | 7.02 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 0.258 | 0.278 | −1.3 | −0.13 | 0.965 | ||

| Age | Unmatched | 38.345 | 45.331 | −67.2 | 99.2 | −20.30 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 38.345 | 48.945 | 1.0 | −0.78 | 0.520 | ||

| Marriage status | Unmatched | 1.826 | 1.322 | −32.1 | 95.1 | −10.13 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 1.826 | 1.190 | 0.7 | −0.60 | 0.676 | ||

| Education level | Unmatched | 2.712 | 2.603 | 11.8 | 94.0 | 30.28 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 2.712 | 2.776 | 2.0 | 5.40 | 0.112 | ||

| Job Income | Unmatched | 50,378.12 | 49,331.02 | 10.4 | 91.1 | 13.09 | 0.003 |

| Matched | 50,378.12 | 50,213.07 | 1.9 | 0.35 | 0.875 | ||

| Smoking History | Unmatched | 0.092 | 0.078 | 11.2 | 99.5 | 6.12 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 0.092 | 0.101 | 3.0 | 0.38 | 0.812 | ||

| Drinking History | Unmatched | 0.067 | 0.012 | 56.0 | 93.4 | 19.13 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 0.067 | 0.109 | 3.6 | 0.77 | 0.529 | ||

| Subjective Well-Being | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | ATT | SE | |

| Unmatched | 2.389 | 2.435 | 0.028 | 0.024 |

| Matched | ||||

| Radius neighbour matching | 2.385 | 3.429 | 0.033 | 0.028 |

| kernel matching | 2.380 | 3.423 | 0.035 | 0.028 |

| Steps | Civil Service Happiness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

| Dependent Variable | Happiness | Self-rated Health | Happiness |

| Internet Use | 0.045 ** (0.042) | 0.130 *** (0.087) | 0.052 ** (0.042) |

| Self-rated Health | 0.495 *** (0.078) | ||

| Control Variables | Control | Control | Control |

| Adj-R2 | 0.0139 | 0.0376 | 0.0134 |

| Sample Size | 3793 | 3793 | 3793 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sui, M.; Ding, H.; Xu, B.; Zhou, M. The Impact of Internet Use on the Happiness of Chinese Civil Servants: A Mediation Analysis Based on Self-Rated Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013142

Sui M, Ding H, Xu B, Zhou M. The Impact of Internet Use on the Happiness of Chinese Civil Servants: A Mediation Analysis Based on Self-Rated Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013142

Chicago/Turabian StyleSui, Mengyuan, Haifeng Ding, Bo Xu, and Mingxing Zhou. 2022. "The Impact of Internet Use on the Happiness of Chinese Civil Servants: A Mediation Analysis Based on Self-Rated Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013142

APA StyleSui, M., Ding, H., Xu, B., & Zhou, M. (2022). The Impact of Internet Use on the Happiness of Chinese Civil Servants: A Mediation Analysis Based on Self-Rated Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013142