School Bullying Is Not a Conflict: The Interplay between Conflict Management Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment

Abstract

1. Introduction

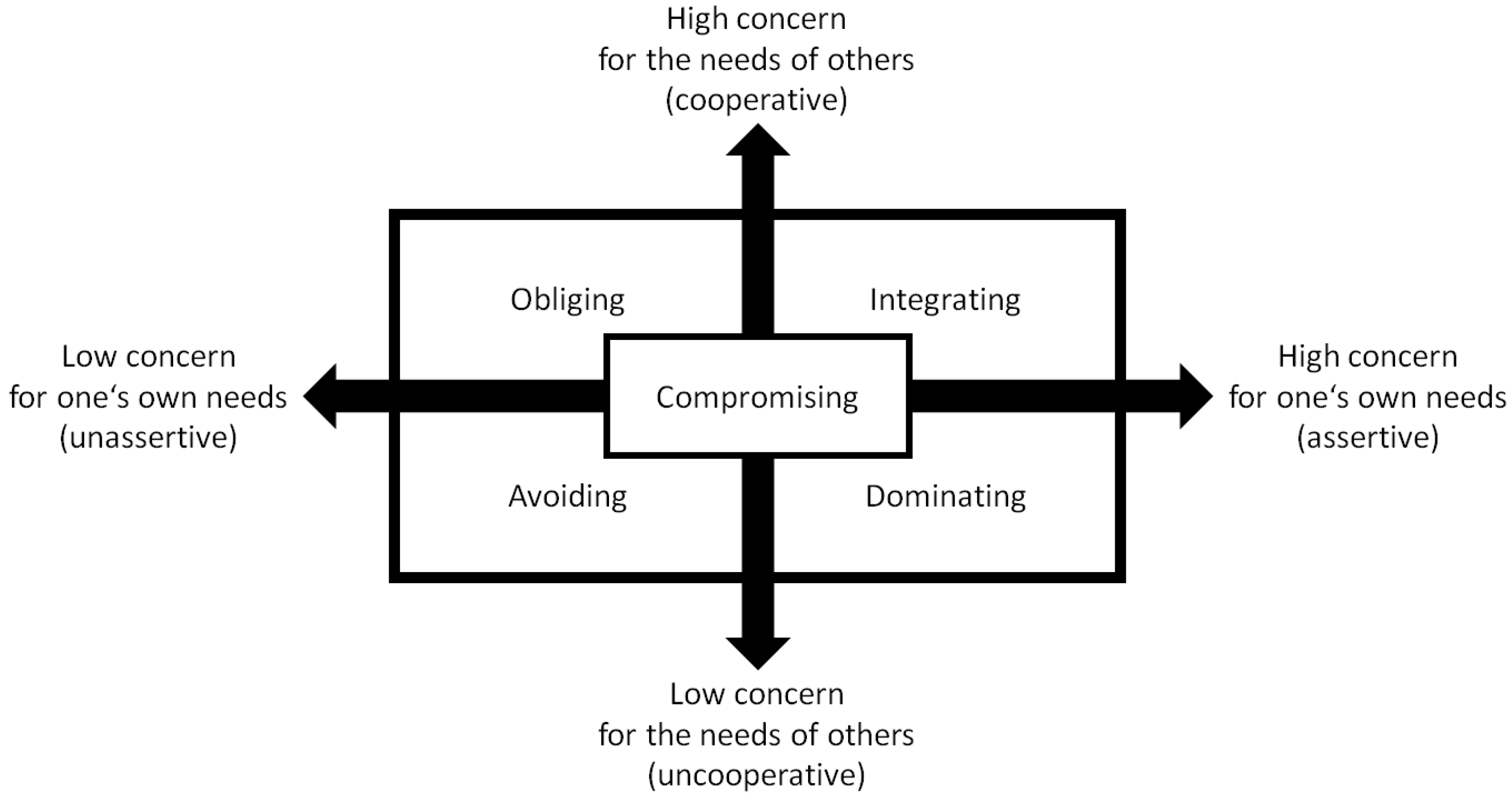

1.1. The Dual Concern Model of Conflict Management Styles

1.2. Conflict Management Styles and Psychological School Adjustment

1.3. Bullying Victimization

1.4. Empirical Findings on the Effects of Conflict Management Styles on Bullying Victimization

1.5. Empirical Findings on the Moderating Effects of Conflict Management Styles on the Negative Effect of Bullying Victimization on School Adjustment

1.6. The Development of Research Hypotheses from the Three Views on Conceptualizing Bullying

1.7. Short-Term Retrospective Measurement of Bullying-Related Behavior

1.8. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Conflict Management Styles

2.3.2. Psychological School Adjustment

2.3.3. Bullying Victimization

2.4. Missing Data

2.5. Data Analysis

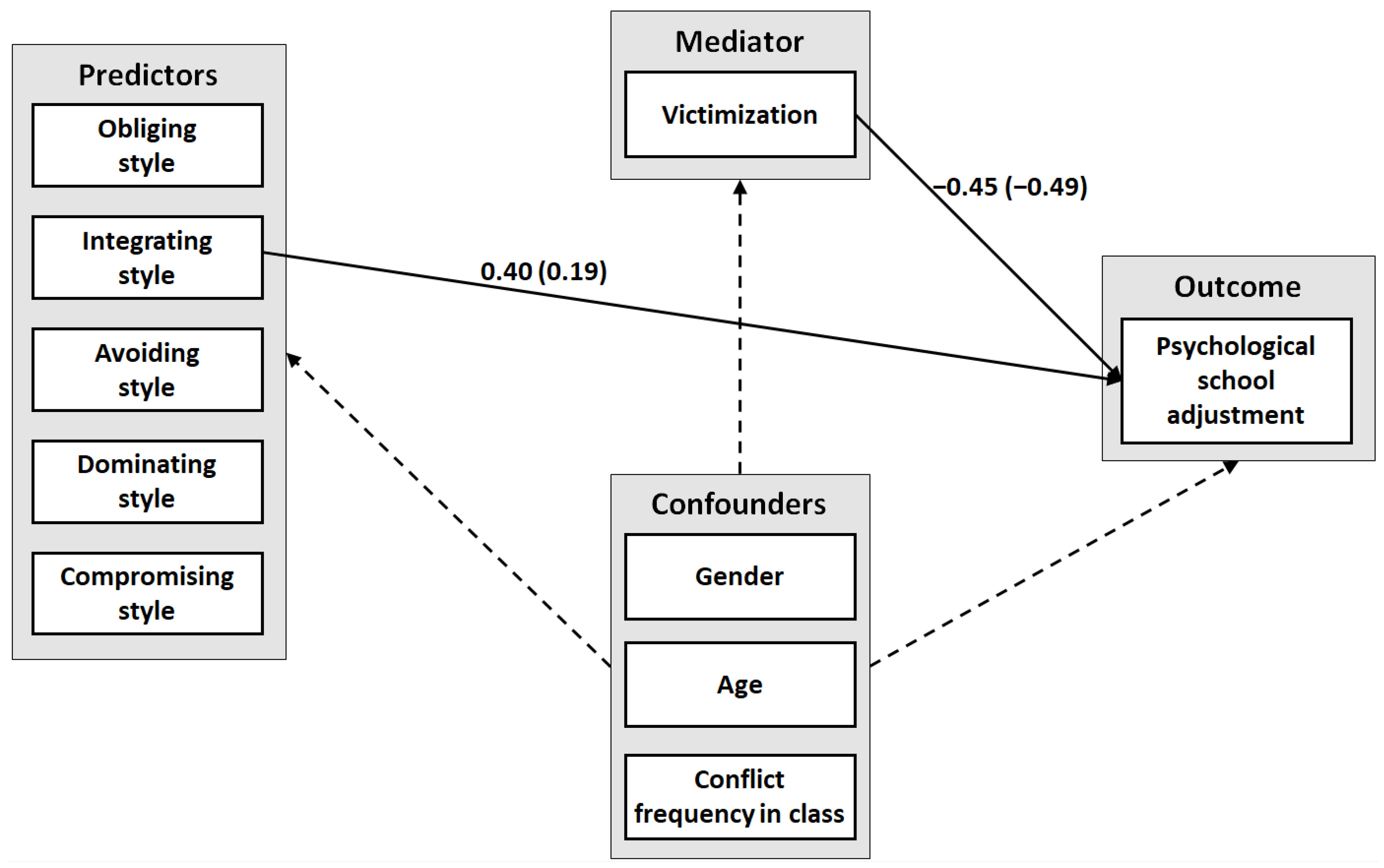

2.5.1. Mediation Analysis

2.5.2. Moderation Analysis

2.5.3. Determination of Person-Oriented Bullying-Related Groups

2.5.4. Differences between Person-Oriented Bullying-Related Groups

3. Results

3.1. Zero-Order Correlations of Main Study Variables

3.2. Mediation Model: Bullying Victimization Mediating Effect of Conflict Management Styles on School Adjustment

3.3. Moderation Model: Conflict Management Styles Moderating the Effect of Victimization on School Adjustment

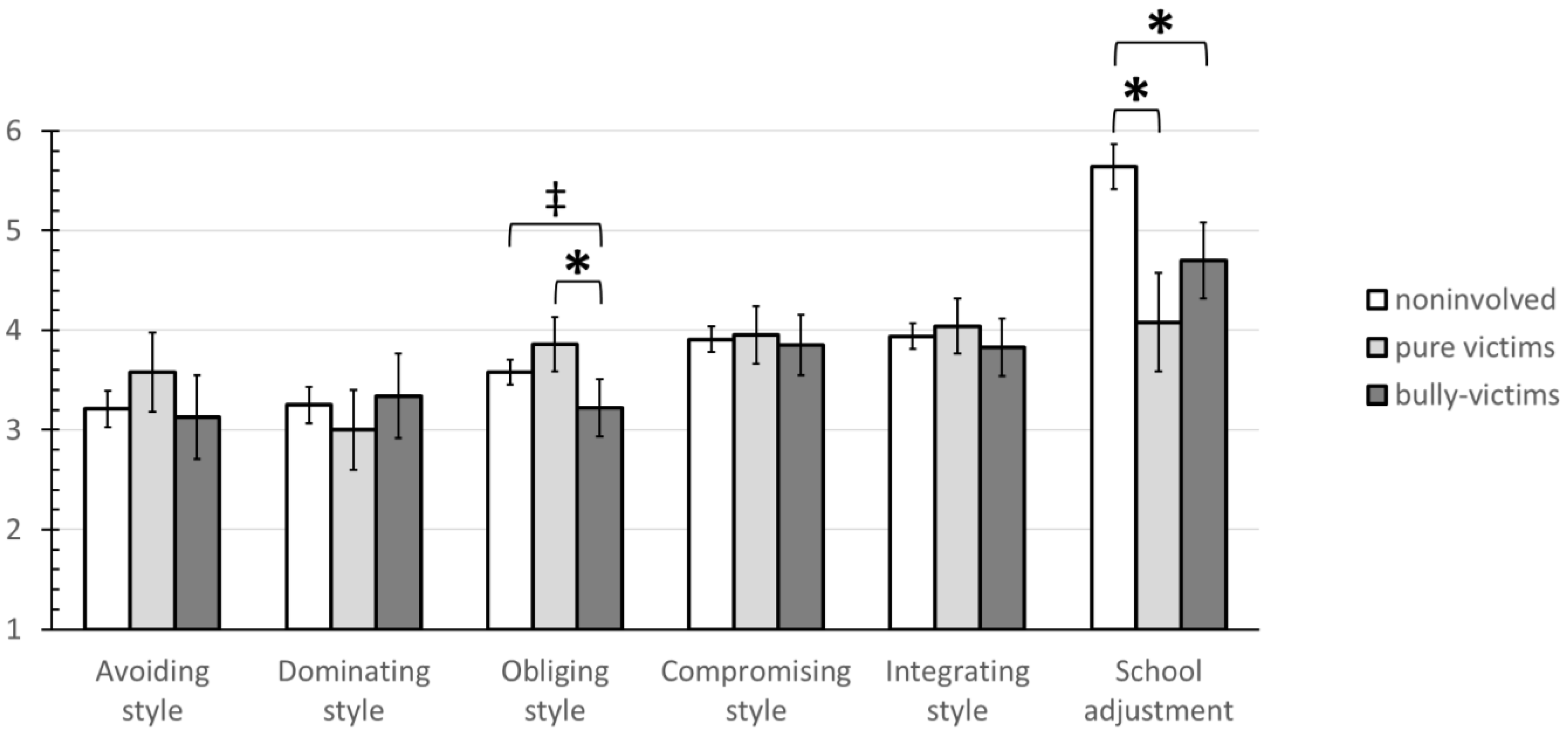

3.4. Person-Oriented Bullying-Related Groups

3.5. Person-Oriented Bulling-Related Group Differences in Conflict Management Styles and Psychological School Adjustment

4. Discussion

4.1. The Integrating Style Positively Impacts Psychological School Adjustment

4.2. Conflict Management Styles Neither Protect against Nor Lead to Victimization

4.3. Conflict Management Styles Neither Reinforce Nor Attenuate the Negative Effects of Victimization on School Adjustment

4.4. Bullying Victimization Is Qualitatively Different from Normal Peer Conflict

4.5. Distinguishing between Victims and Bully-Victims Brings Additional Insights

4.6. Theoretical Implications

4.7. Practical Implications

4.8. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zapf, D.; Gross, C. Conflict Escalation and Coping with Workplace Bullying: A Replication and Extension. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, G.; Bonsignore, V.; Diamantini, D. Conflict Management among Secondary School Students. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 2402–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bickmore, K. Policies and Programming for Safer Schools: Are “anti-Bullying” Approaches Impeding Education for Peacebuilding? Educ. Policy 2010, 25, 648–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, S. The Role of Elementary School Counselors in Reducing School Bullying. Elem. Sch. J. 2008, 108, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A. Toward a Theory of Managing Organizational Conflict. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2002, 13, 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780631192411. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier, D.; Solomontos-Kountouri, O.; Burger, C.; Doğan, A. Cross-National Evaluation of the ViSC Social Competence Programme: Effects on Teachers. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective on Adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, M.A.; Dunfield, K.A.; Recchia, H.E. Prosocial Behavior with Peers: Intentions, Outcomes, and Interpersonal Adjustment. In Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups; Bukowski, W.M., Laursen, B., Rubin, K.H., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Legkauskas, V.; Magelinskaitė-Legkauskienė, Š. Social Competence in the 1st Grade Predicts School Adjustment Two Years Later. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 191, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Afonso Lourenço, A.; Németh, Z. School Conflicts: Causes and Management Strategies in Classroom Relationships. In Interpersonal Relationships; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M.A.; Katz, J.P. Forty Years of Conflict: The Effects of Gender and Generation on Conflict-Management Strategies. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 31, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.A.; Tidd, S.T.; Currall, S.C.; Tsai, J.C. What Goes around Comes around: The Impact of Personal Conflict Style on Work Conflict and Stress. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2000, 11, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockenberg, S.; Lourie, A. Parents’ Conflict Strategies with Children and Children’s Conflict Strategies with Peers. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 1996, 42, 495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky, W.; Wülker, A. Konfliktstile: Adaptation Und Erprobung Des Rahim Organizational Conflict Inventory (ROCI-II) [Conflict Styles: Adaptation and Testing of the Rahmin Organizational Conflict Inventory, ROCI-II]. Available online: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/psyifp/aebilsky/fb_21neu.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Tehrani, H.D.; Yamini, S. Personality Traits and Conflict Resolution Styles: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 157, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P.; Fletcher, C.V. Conflict Motivations and Tactics of Targets, Bystanders, and Bullies: A Thrice-Told Tale of Workplace Bullying. In The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Communication; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 349–376. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, S.; Lourenço, A.A. Conflict in the Classroom: How Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence Influences Conflict Management. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S. The Conflict Management Styles Used by Managers of Private Primary Schools: An Example of Ankara; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Zurlo, M.C.; Vallone, F.; Dell’Aquila, E.; Marocco, D. Teachers’ Patterns of Management of Conflicts with Students: A Study in Five European Countries. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somech, A. Managing Conflict in School Teams: The Impact of Task and Goal Interdependence on Conflict Management and Team Effectiveness. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyildirim, G.; Kayikçi, K. The Conflict Management Strategies of School Administrators While Conflicting with Their Supervisors. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Bullock, A.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; French, D. Moderating Role of Conflict Resolution Strategies in the Links between Peer Victimization and Psychological Adjustment among Youth. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R. School Adjustment. In Handbook of psychology; Reynolds, W.M., Miller, G.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York City, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, S.H.; Ladd, G.W. Interpersonal Relationships in the School Environment and Children’s Early School Adjustment: The Role of Teachers and Peers. In Social Motivation; Juvonen, J., Wentzel, K.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M.A.; Guerrero, L.K. Managing Conflict Appropriately and Effectively: An Application of The Competence Model to Rahim’s Organizational Conflict Styles. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2000, 11, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A. Managing Conflict in Organizations, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Yan, G.A.; Moeller, C. The Psychosocial Costs of Conflict Management Styles. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2010, 21, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, K.; Zahn-Waxler, C.; Shirtcliff, E.A.; Schreiber, J.E.; Hastings, P.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Adolescents’, Mothers’, and Fathers’ Gendered Coping Strategies during Conflict: Youth and Parent Influences on Conflict Resolution and Psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D.; Mevissen, N. Aggressive Behavior of Passengers, Conflict Management Behavior, and Burnout among Trolley Car Drivers. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2002, 9, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Kraus, L.A.; Capobianco, S. Age Differences in Responses to Conflict in the Workplace. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2009, 68, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colsman, M.; Wulfert, E. Conflict Resolution Style as an Indicator of Adolescents’ Substance Use and Other Problem Behaviors. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, D.Y.; Ho, A.K.-K. Focus on Opportunities or Limitations? Their Effects on Older Workers’ Conflict Management. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, M.T.M.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Evers, A.; van Dierendonck, D. Passive Responses to Interpersonal Conflict at Work Amplify Employee Strain. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.D.; LaVoie, J.C.; Spenceri, M.C.; Mahoney-Wernli, M.A. Peer Conflict Avoidance: Associations with Loneliness, Social Anxiety, and Social Avoidance. Psychol. Rep. 2001, 88, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Patel, P. Consequences of Repression of Emotion: Physical Health, Mental Health and General Well Being. Int. J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 2019, 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Schoenfeld, M.B.; Flores, E.J. Predicting Conflict Acts Using Behavior and Style Measures. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2017, 29, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClowry, R.J.; Miller, M.N.; Mills, G.D. What Family Physicians Can Do to Combat Bullying. J. Fam. Pract. 2017, 66, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, L.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E. The Teacher’s Role in Preventing Bullying. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G.; Van der Heijden, B.; Guenter, H.; Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. Do Interpersonal Conflict, Aggression and Bullying at the Workplace Overlap? A Latent Class Modeling Approach. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raver, J.L. Counterproductive Work Behavior and Conflict: Merging Complementary Domains. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2013, 6, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Moore, M. Critical Issues for Teacher Training to Counter Bullying and Victimisation in Ireland. Aggress. Behav. 2000, 26, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiesen, S.B.; Aasen, E.; Holst, G.; Wie, K.; Einarsen, S. The Escalation of Conflict: A Case Study of Bullying at Work. Int. J. Manag. Decis. Mak. 2003, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Bollen, K.; Euwema, M.; De Witte, H. Conflicts and Conflict Management Styles as Precursors of Workplace Bullying: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 23, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Escartín, J.; Gross, C.; Zapf, D. Towards a Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation between Workplace Bullying and Interpersonal Conflict. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keashly, L.; Minkowitz, H.; Nowell, B.L. Conflict, Conflict Resolution and Workplace Bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 331–361. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and Bullying at Work. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.J.; Kendall, G.E.; Burns, S.K.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Kane, R.T. Measuring 8 to 12 Year Old Children’s Self-Report of Power Imbalance in Relation to Bullying: Development of the Scale of Perceived Power Imbalance. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, T.; Duncan, L.; Cecil, C.M.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Pingault, J.-B. Quasi-Experimental Evidence on Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Bullying Victimization: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Bachmann, L. Perpetration and Victimization in Offline and Cyber Contexts: A Variable- and Person-Oriented Examination of Associations and Differences Regarding Domain-Specific Self-Esteem and School Adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, B.J.; Ladd, G.W. Peer Victimization: Cause or Consequence of School Maladjustment? Child Dev. 1996, 67, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanek, E.; Strohmeier, D.; Yanagida, T. Depression in Groups of Bullies and Victims: Evidence for the Differential Importance of Peer Status, Reciprocal Friends, School Liking, Academic Self-Efficacy, School Motivation and Academic Achievement. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2017, 11, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhs, E.S.; Ladd, G.W.; Herald, S.L. Peer Exclusion and Victimization: Processes That Mediate the Relation between Peer Group Rejection and Children’s Classroom Engagement and Achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosier, M.E.; Kupersmidt, J.B.; Patterson, C.J. Children’s Academic and Behavioral Adjustment as a Function of the Chronicity and Proximity of Peer Rejection. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, R.; Benbenishty, R. Perceptions of Teachers’ Support, Safety, and Absence from School Because of Fear among Victims, Bullies, and Bully-Victims. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2012, 82, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartia, M. The Sources of Bullying–Psychological Work Environment and Organizational Climate. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoko, O.B.; Callan, V.J.; Härtel, C.E.J. Workplace Conflict, Bullying, and Counterproductive Behaviors. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2003, 11, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; De Witte, H. The Relationship Between the Occurrence of Conflicts in the Work Unit, the Conflict Management Styles in the Work Unit and Workplace Bullying. Psychol. Belg. 2010, 49, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mack, D.A.; Shannon, C.; Quick, J.D.; Quick, J.C. Stress and the Preventative Management of Workplace Violence. In Dysfunctional Behavior in Organizations: Violent and Deviant Behavior; Griffin, R.W., O’Leary-Kelly, A., Collins, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 119–141. ISBN 0-7623-0454-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D. Organisational, Work Group Related and Personal Causes of Mobbing/Bullying at Work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, C. From Research to Implementation: Finding Leverage for Prevention. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.A.; Rospenda, K.M.; Flaherty, J.A.; Freels, S. Workplace Harassment, Active Coping, and Alcohol-Related Outcomes. J. Subst. Abuse 2001, 13, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubisky, P.; Ting-Toomey, S.; Lin, S.-L. The Influence of Individualism-Collectivism and Self-Monitoring on Conflict Styles. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 1991, 15, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, K.V.; Fauske, M.R.; Reknes, I.; Nielsen, M.B.; Gjerstad, J.; Einarsen, S.V. Preventing and Neutralizing the Escalation of Workplace Bullying: The Role of Conflict Management Climate. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Raising Voice, Risking Retaliation: Events Following Interpersonal Mistreatment in the Workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, D.G.; Brockenbrough, K. Identification of Bullies and Victims. J. Sch. Violence 2004, 3, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasking, P.; Tatnell, R.C.; Martin, G. Adolescents’ Reactions to Participating in Ethically Sensitive Research: A Prospective Self-Report Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.L.; Darnell, D.; Anthony, E.R.; Tusher, C.P.; Zimmerman, L.; Enkhtor, D.; Hipp, T.N. Investigating the Effects of Trauma-Related Research on Well-Being. Account. Res. 2011, 18, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundh, L.-G. The Crisis in Psychological Science and the Need for a Person-Oriented Approach. In Social Philosophy of Science for the Social Sciences; Valsiner, J., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.; Li, X.; Salmivalli, C. Maladjustment of Bully-Victims: Validation with Three Identification Methods. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 1390–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C. Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss-Sampson, M.A. Statistical Analysis in JASP 0.14: A Guide for Students. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Statistical-Analysis-in-JASP-A-Students-Guide-v14-Nov2020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Hayes, A.F.; Little, T.D. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York City, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini, E.; Camodeca, M. Shame and Guilt as Behaviour Regulators: Relationships with Bullying, Victimization and Prosocial Behaviour. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 26, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollerová, L.; Janošová, P.; Říčan, P. Good and Evil at School: Bullying and Moral Evaluation in Early Adolescence. J. Moral Educ. 2014, 43, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Antonioni, D. Personality, Reciprocity, and Strength of Conflict Resolution Strategy. J. Res. Pers. 2007, 41, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, M.J.; Canary, D.J. Conflict in Organizations: A Competence-Based Approach. In Conflict and Organizations: Communicative Processes; Nicotera, A.M., Ed.; State University of New York: Albany, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zee, K.; Hofhuis, J. Conflict Management Styles across Cultures. In The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Raver, J.L.; Barling, J. Workplace Aggression and Conflict: Constructs, Commonalities, and Challenges for Future Inquiry. In The Psychology of Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations; De Dreu, C.K.W., Gelfand, M.J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York City, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 211–244. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.W. Conflict and Negotiation Processes in Organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 651–717. [Google Scholar]

- Latipun, S.; Nasir, R.; Zainah, A.Z.; Khairudin, R. Effectiveness of Peer Conflict Resolution Focused Counseling in Promoting Peaceful Behavior among Adolescents. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.; Tamburrino, M. Bullying among Young Children: Strategies for Prevention. Early Child. Educ. J. 2013, 42, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydenberk, W.; Heydenberk, R. More than Manners: Conflict Resolution in Primary Level Classrooms. Early Child. Educ. J. 2007, 35, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydenberk, R.A.; Heydenberk, W.R.; Tzenova, V. Conflict Resolution and Bully Prevention: Skills for School Success. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2006, 24, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-M.; Chang, L.Y.C.; Cheng, Y.-Y. Choosing to Be a Defender or an Outsider in a School Bullying Incident: Determining Factors and the Defending Process. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 37, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Spröber, N.; Bauman, S.; Rigby, K. How Teachers Respond to School Bullying: An Examination of Self-Reported Intervention Strategy Use, Moderator Effects, and Concurrent Use of Multiple Strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Kollerová, L. Teachers Can Make a Difference in Bullying: Effects of Teacher Interventions on Students’ Adoption of Bully, Victim, Bully-Victim or Defender Roles across Time. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.; Sperry, L. Understanding and Defining Mobbing. In Mobbing: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions; Duffy, M., Sperry, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York City, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Elgoibar, P.; Euwema, M.; Munduate, L. Conflict Management. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arënliu, A.; Strohmeier, D.; Konjufca, J.; Yanagida, T.; Burger, C. Empowering the Peer Group to Prevent School Bullying in Kosovo: Effectiveness of a Short and Ultra-Short Version of the ViSC Social Competence Program. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2020, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczen, N.; Abs, H.J.; Filsecker, M. How School Influences Adolescents’ Conflict Styles. J. Peace Educ. 2017, 14, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting-Toomey, S.; Yee-Jung, K.K.; Shapiro, R.B.; Garcia, W.; Wright, T.J.; Oetzel, J.G. Ethnic/Cultural Identity Salience and Conflict Styles in Four US Ethnic Groups. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2000, 24, 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01. Gender (0 = female) | 0.23 | – | — | |||||||||||

| 02. Age | 22.63 | 2.13 | −0.04 | — | ||||||||||

| 03. Class conflict frequency | 2.91 | 0.91 | 0.03 | −0.02 | — | |||||||||

| 04. Pure victim (0 = no) | 0.14 | – | −0.0003 | −0.11 | 0.21 ** | — | ||||||||

| 05. Bully−victim (0 = no) | 0.12 | – | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.21 ** | −0.15 ‡ | — | |||||||

| 06. Victimization | 1.89 | 1.47 | −0.03 | −0.1 | 0.43 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.92 | ||||||

| 07. Integrating CM style | 3.92 | 0.68 | −0.004 | −0.05 | −0.25 ** | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.14 ‡ | 0.85 | |||||

| 08. Obliging CM style | 3.57 | 0.67 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.21 ** | 0.14 ‡ | −0.23 ** | −0.12 | 0.40 *** | 0.80 | ||||

| 09. Avoiding CM style | 3.33 | 0.94 | −0.15 * | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.14 ‡ | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.43 *** | 0.84 | |||

| 10. Dominating CM style | 3.13 | 0.95 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.15 ‡ | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.23 ** | −0.26 *** | −0.38 *** | 0.84 | ||

| 11. Compromising CM style | 3.88 | 0.68 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.17 * | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.13 ‡ | 0.67 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.74 | |

| 12. Psych. school adjustment | 5.24 | 1.35 | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.37 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.24 ** | −0.57 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.06 | −0.14 ‡ | −0.01 | 0.21 ** | 0.93 |

| 95% CI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Mediator | Outcome | Estimate | SE | z | p | Lower | Upper | Std (nox) |

| Total effects | |||||||||

| Integrating | — | School adjustment | 0.346 ‡ | 0.209 | 1.661 | 0.097 | −0.062 | 0.755 | 0.165 ‡ |

| Obliging | — | School adjustment | −0.132 | 0.183 | −0.718 | 0.473 | −0.491 | 0.228 | −0.064 |

| Avoiding | — | School adjustment | −0.213 ‡ | 0.122 | −1.738 | 0.082 | −0.453 | 0.027 | −0.147 ‡ |

| Dominating | — | School adjustment | −0.115 | 0.116 | −0.991 | 0.322 | −0.343 | 0.113 | −0.080 |

| Compromising | — | School adjustment | 0.166 | 0.188 | 0.883 | 0.377 | −0.203 | 0.534 | 0.081 |

| Direct effects | |||||||||

| Integrating | — | School adjustment | 0.397 * | 0.181 | 2.186 | 0.029 | 0.041 | 0.752 | 0.189 * |

| Obliging | — | School adjustment | −0.195 | 0.160 | −1.222 | 0.222 | −0.508 | 0.118 | −0.095 |

| Avoiding | — | School adjustment | −0.161 | 0.107 | −1.513 | 0.130 | −0.370 | 0.048 | −0.111 |

| Dominating | — | School adjustment | −0.129 | 0.101 | −1.269 | 0.204 | −0.327 | 0.070 | −0.089 |

| Compromising | — | School adjustment | 0.098 | 0.164 | 0.597 | 0.551 | −0.223 | 0.418 | 0.048 |

| Indirect effects | |||||||||

| Integrating | Victimization | School adjustment | −0.050 | 0.104 | −0.483 | 0.629 | −0.253 | 0.153 | −0.024 |

| Obliging | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.063 | 0.091 | 0.693 | 0.488 | −0.116 | 0.243 | 0.031 |

| Avoiding | Victimization | School adjustment | −0.052 | 0.061 | −0.844 | 0.399 | −0.171 | 0.068 | −0.036 |

| Dominating | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.230 | 0.818 | −0.101 | 0.127 | 0.009 |

| Compromising | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.068 | 0.094 | 0.730 | 0.466 | −0.115 | 0.252 | 0.033 |

| Effect on SchoolAdjustment | SE | t Value | p Value | Lower Level 95% CI | Upper Level 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.931 *** | 0.843 | 5.849 | <0.001 | 3.265 | 6.597 |

| Confounders | ||||||

| Gender | 0.139 | 0.159 | 0.875 | 0.383 | −0.175 | 0.454 |

| Age | 0.039 | 0.035 | 1.104 | 0.271 | −0.031 | 0.109 |

| Class conflict frequency | −0.200 ‡ | 0.117 | −1.705 | 0.090 | −0.432 | 0.032 |

| Conditional main effects | ||||||

| Victimization | −0.464 *** | 0.073 | −6.372 | <0.001 | −0.608 | −0.320 |

| Integrating style | 0.443 * | 0.181 | 2.456 | 0.015 | 0.087 | 0.800 |

| Obliging style | −0.211 | 0.146 | −1.446 | 0.150 | −0.500 | 0.077 |

| Avoiding style | −0.149 | 0.107 | −1.401 | 0.163 | −0.360 | 0.061 |

| Dominating style | −0.096 | 0.101 | −0.952 | 0.343 | −0.297 | 0.104 |

| Compromising style | 0.099 | 0.174 | 0.568 | 0.571 | −0.245 | 0.443 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||

| Victimization*integrating style | −0.245 * | 0.124 | −1.974 | 0.050 | −0.490 | 0.000 |

| Victimization*obliging style | −0.064 | 0.103 | −0.621 | 0.536 | −0.269 | 0.140 |

| Victimization*avoiding style | 0.064 | 0.082 | 0.786 | 0.433 | −0.097 | 0.225 |

| Victimization*dominating style | −0.014 | 0.078 | −0.182 | 0.856 | −0.168 | 0.140 |

| Victimization*compromising style | 0.206 | 0.139 | 1.480 | 0.141 | −0.069 | 0.481 |

| Noninvolved | Pure Victims | Bully-Victims | Comparison Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency comparison | Χ2(2) | ||||

| Sample size (%) | 125 (74.0%) | 23 (13.6%) | 21 (12.4%) | 125.586 *** | |

| Number of females (%) | 96 (76.8%) | 17 (73.9%) | 16 (76.2%) | 0.100 | |

| Mean comparison | F(2,166) | ηp2 | |||

| Age (SD) | 22.72 (2.16) | 22.04 (2.08) | 22.71 (2.05) | 0.993 | 0.012 |

| Frequency of conflicts in class (SD) | 2.74 (0.78) | 3.39 (1.12) | 3.43 (1.03) | 9.807 *** | 0.106 |

| Noninvolved | Pure Victims | Bully-Victims | ANCOVA Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict Management Styles and School Adjustment | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | F(2, 161) | ηp2 |

| Integrating style | 3.94 | 0.065 | 4.04 | 0.141 | 3.83 | 0.148 | 0.592 | 0.008 |

| Obliging style | 3.58 | 0.064 | 3.86 c | 0.140 | 3.22 b | 0.147 | 5.500 ** | 0.064 |

| Avoiding style | 3.21 | 0.094 | 3.58 | 0.203 | 3.13 | 0.214 | 1.738 | 0.021 |

| Dominating style | 3.25 | 0.094 | 3.00 | 0.205 | 3.34 | 0.216 | 0.877 | 0.011 |

| Compromising style | 3.91 | 0.067 | 3.95 | 0.147 | 3.85 | 0.154 | 0.214 | 0.003 |

| Psychological school adjustment | 5.64 bc | 0.116 | 4.08 a | 0.252 | 4.70 a | 0.265 | 19.641 *** | 0.196 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burger, C. School Bullying Is Not a Conflict: The Interplay between Conflict Management Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811809

Burger C. School Bullying Is Not a Conflict: The Interplay between Conflict Management Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811809

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurger, Christoph. 2022. "School Bullying Is Not a Conflict: The Interplay between Conflict Management Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811809

APA StyleBurger, C. (2022). School Bullying Is Not a Conflict: The Interplay between Conflict Management Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811809