The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms and Their Socioeconomic and Health Predictors in a Local Community with a High Deprivation: A Cross-Sectional Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

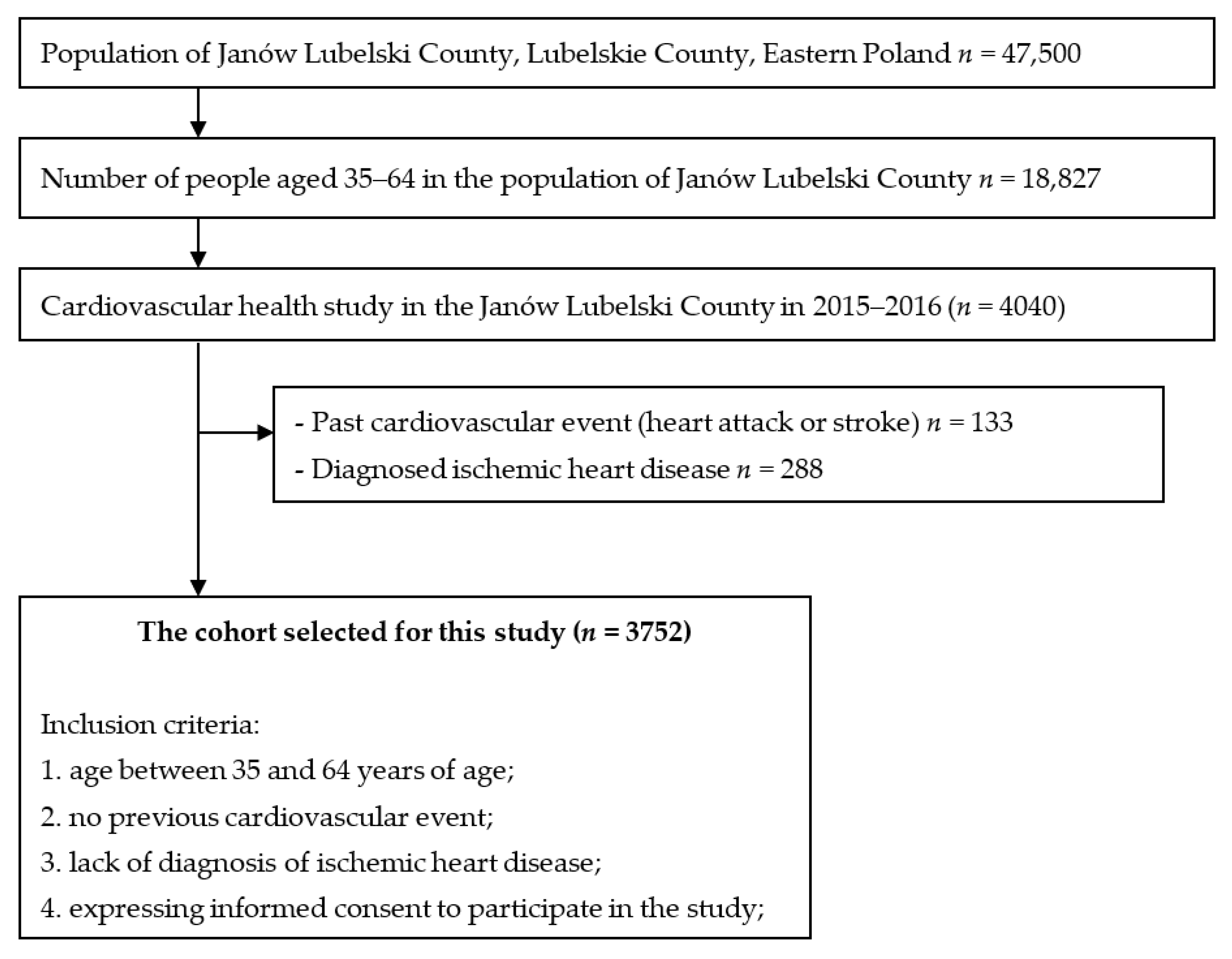

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

2.2.3. Other Socioeconomic and Health Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Relationship between Sociodemographic Variables and the Risk of Depression Symptoms

3.3. Relationship between the Risk of Developing Depression Symptoms and Socioeconomic and Health Variables in Multivariate Models in Gender Strata

4. Discussion

The Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labonté, B.; Engmann, O.; Purushothaman, I.; Menard, C.; Wang, J.; Tan, C.; Scarpa, J.R.; Moy, G.; Loh, Y.E.; Cahill, M.; et al. Sex-specific transcriptional signatures in human depression. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- EUROSTAT. Statistics Explained. Mental Health and Related Issues Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Mental_health_and_related_issues_statistics (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- The Economist. The Economist the Global Crisis of Depression, The Low of 21st Century; Summary Report, The Economist Events; The Economist Newspaper Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Moskalewicz, J.; Kiejna, A.; Wojtyniak, B. Kondycja Psychiczna Mieszkańców Polski; Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bromet, E.; Andrade, L.H.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Alonso, J.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Hu, C.; Iwata, N.; et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Koyanagi, A.; Chatterji, S.; Leonardi, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Koskinen, S.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Haro, J.M. The role of socioeconomic status in depression: Results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvó-Perxas, L.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Vilalta-Franch, J. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of depressive and bipolar disorders in Catalonia (Spain) using DSM-5 criteria. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 184, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Bermúdez-Tamayo, C.; Rodríguez-Barranco, M. Socio-economic factors linked with mental health during the recession: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Equity. Health 2017, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaros, D. Twenty years after the economic restructuring of Eastern Europe: An economic review. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2008, 7, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyniak, B.; Moskalewicz, J.; Stokwiszewski, J.; Rabczenko, D. Gender-specific mortality associated with alcohol consumption in Poland in transition. Addiction 2005, 100, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinsalu, M.; Stirbu, I.; Vågerö, D.; Kalediene, R.; Kovács, K.; Wojtyniak, B.; Wróblewska, W.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Kunst, A.E. Educational inequalities in mortality in four Eastern European countries: Divergence in trends during the post-communist transition from 1990 to 2000. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinowska, S.; Sowa, A.; Topór-Mądry, R. Health Status and Health Care Systems in Central & Eastern European Countries: Bulgaria, Estonia, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary; European Network of Economic Policy, Research Report No. 31; European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in Central and Eastern Europe: Synthesis of results of eight new studies. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galobardes, B.; Shaw, M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Lynch, J.W.; Davey Smith, G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smętkowski, M.; Gorzelak, G.; Płoszaj, A.; Rok, J. Poviats threatened by deprivation: State, trends and prospects. EUROREG Rep. Anal. 2015, 7, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office (GUS). Report on Results. National Census of Population and Apartments 2011. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/lud_raport_z_wynikow_NSP2011.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Statistical Office in Lublin, Poland. Registered Unemployment in Lubelskie Voivodship in 2014. Available online: http://wuplublin.praca.gov.pl/-/1355901-sytuacja-na-rynku-pracy-w-wojewodztwie-lubelskim-luty-2015 (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Central Statistical Office (GUS). Beneficiaries of Social Assistance and Family Benefits in 2012. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5487/6/3/5/beneficjenci_pomocy_spolecznej_i_swiadczen_rodzinnych_2012.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Program PL 13. Publication of Mortality Rates for Selected Districts. Available online: http://archiwum.zdrowie.gov.pl/aktualnosc-27-2136-Program_PL_13___publikacja_wskaznikow_umieralnosci_dla_wybranych_powiatow.html (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A.L.; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Baumann, L.C.; Davidson, K.W.; Ebell, M.; García, F.A.; Gillman, M.; Herzstein, J.; et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016, 315, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D.; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 365, l1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarska, B.J.; Nowicki, G.; Piasecka, H.; Zarzycka, D.; Mazur, A.; Saran, T.; Bednarek, A. Validation of the Polish language version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in a population of adults aged 35–64. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee; WHO Technical Report Series 854; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi, S.; Chatterji, S.; Verdes, E.; Tandon, A.; Patel, V.; Ustun, B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007, 370, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michas, G.; Magriplis, E.; Micha, R.; Chourdakis, M.; Chrousos, G.P.; Roma, E.; Dimitriadis, G.; Panagiotakos, D.; Zampelas, A. Sociodemographic and lifestyle determinants of depressive symptoms in a nationally representative sample of Greek adults: The Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS). J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, F.; Zillich, L.; Frank, J.; Kleineidam, L.; Wagner, M.; Baune, B.T.; Klinger-König, J.; Grabe, H.J.; Pabst, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; et al. Lifetime and current depression in the German National Cohort (NAKO). World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Vargas-Fernández, R.; Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Grendas, L.N. Depression in the Peruvian population and its associated factors: Analysis of a national health survey. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 273, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Califf, R.M.; Wong, C.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Hong, D.S.; Miller, D.P.; Mega, J.L.; Baseline Study Group. Importance of social determinants in screening for depression. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 2736–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.; Saburova, L.; Bobrova, N.; Avdeeva, E.; Malyutina, S.; Kudryavtsev, A.V.; Leon, D.A. Socio-demographic, behavioural and psycho-social factors associated with depression in two Russian cities. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Velde, S.; Bracke, P.; Levecque, K. Gender differences in depression in 23 European countries. Cross-national variation in the gender gap in depression. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maske, U.E.; Busch, M.A.; Jacobi, F.; Beesdo-Baum, K.; Seiffert, I.; Wittchen, H.U.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Hapke, U. Current major depressive syndrome measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Results from a cross-sectional population-based study of adults in Germany. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromaa, E.; Tolvanen, A.; Tuulari, J.; Wahlbeck, K. Personal stigma and use of mental health services among people with depression in a general population in Finland. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, M.; Wilkinson, G. Gender differences in depression. Critical review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgunova, L.; Laryushina, Y.; Turmukhambetova, A.; Koichubekov, B.; Sorokina, M.; Korshukov, I. The incidence of depression among the population of Central Kazakhstan and its relationship with sociodemographic characteristics. Behav. Neurol. 2017, 2017, 2584187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.Y.; Huang, S.C.; Liu, P.L.; Yeung, K.T.; Wang, Y.M.; Yang, H.J. The interaction between exercise and marital status on depression: A cross-sectional study of the Taiwan Biobank. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Lai, W.; Long, E.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhong, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y. Is old age depressing? Growth trajectories and cohort variations in late-life depression. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, U.; Chen, L.A. Characteristics, correlates, and outcomes of childhood and adolescent depressive disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, G.S. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005, 365, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romans, S.; Cohen, M.; Forte, T. Rates of depression and anxiety in urban and rural Canada. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, A.J.; Schertz, K.E.; Rim, N.W.; Cardenas-Iniguez, C.; Lahey, B.B.; Bettencourt, L.M.A.; Berman, M.G. Evidence and theory for lower rates of depression in larger US urban areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022472118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wal, J.M.; van Borkulo, C.D.; Deserno, M.K.; Breedvelt, J.J.F.; Lees, M.; Lokman, J.C.; Borsboom, D.; Denys, D.; van Holst, R.J.; Smidt, M.P.; et al. Advancing urban mental health research: From complexity science to actionable targets for intervention. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenborn, A.K.; Rahmandad, H.; Rick, J.; Hosseinichimeh, N. Depression as a systemic syndrome: Mapping the feedback loops of major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, K.B.S.; Finnemann, A.; van den Ende, M.W.J.; Sloot, P.M.A. No robust relation between larger cities and depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118943118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haim, A.; Zubidat, A.E. Artificial light at night: Melatonin as a mediator between the environment and epigenome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoli, M.; Grassi, S.; Caldiroli, A.; Carnevali, G.S.; Mucci, F.; Iodice, S.; Cantone, L.; Pergoli, L.; Bollati, V. Is there a link between air pollution and mental disorders? Environ. Int. 2018, 118, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Copez-Lonzoy, A.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Bazo-Alvarez, J.C. Valid group comparisons can be made with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A measurement invariance study across groups by demographic characteristics. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, C.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Yoon, S.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jeon, S.W.; Han, C. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.W.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, D.J. The prevalence of and factors associated with depressive symptoms in the Korean adults: The 2014 and 2016 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Land, K.C.; Blazer, D.; Fillenbaum, G.G.; Branch, L.G. Educational status and active life expectancy among older blacks and whites. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Mundó, J.; Leonardi, M.; Chatterji, S.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Koskinen, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Haro, J.M. The association between socioeconomic status and depression among older adults in Finland, Poland and Spain: A comparative cross-sectional study of distinct measures and pathways. J. Affect Disord. 2018, 241, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Farrell, L. Alcohol and depression: Evidence from the 2014 health survey for England. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 180, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, M.X.; Dumith, S.C.; Loret de Mola, C.; Neiva-Silva, L. Sociodemographic, behavioral, and health-related risk factors for depression among men and women in a southern Brazilian city. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2019, 41, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, M.; Hamer, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Batty, G.D.; Kivimäki, M. Association of metabolically healthy obesity with depressive symptoms: Pooled analysis of eight studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, A.; Zhou, A.; Power, C.; Hyppönen, E. Obesity and depressive symptoms in mid-life: A population-based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Anderson, D.; Lurie-Beck, J. The relationship between abdominal obesity and depression in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 5, e267–e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Schuppenies, A.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J. Approaching the shared biology of obesity and depression: The stress axis as the locus of gene-environment interactions. Mol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, S.K.; Ryoo, J.H.; Oh, C.M.; Mansur, R.B.; Alfonsi, J.E.; Cha, D.S.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R.S.; Jung, J.Y. The association between insulin resistance and depression in the Korean general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinridders, A.; Cai, W.; Cappellucci, L.; Ghazarian, A.; Collins, W.R.; Vienberg, S.G.; Pothos, E.N.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin resistance in brain alters dopamine turnover and causes behavioral disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3463–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amtmann, D.; Bamer, A.M.; Kim, J.; Chung, H.; Salem, R. People with multiple sclerosis report significantly worse symptoms and health related quality of life than the US general population as measured by PROMIS and NeuroQoL outcome measures. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahieu, M.A.; Ahn, G.E.; Chmiel, J.S.; Dunlop, D.D.; Helenowski, I.B.; Semanik, P.; Song, J.; Yount, S.; Chang, R.W.; Ramsey-Goldman, R. Fatigue, patient reported outcomes, and objective measurement of physical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2016, 25, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homco, J.; Rodriguez, K.; Bardach, D.R.; Hahn, E.A.; Morton, S.; Anderson, D.; Kendrick, D.; Scholle, S.H. Variation and change over time in promis-29 survey results among primary care patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Patient Cent. Res. Rev. 2019, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.Y.; Wan, E.Y.; Choi, E.P.; Chan, K.T.; Lam, C.L. The 12-month incidence and predictors of PHQ-9-screened depressive symptoms in Chinese primary care patients. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Watkins, L.L.; Koch, G.G.; Sherwood, A.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Davidson, J.R.; O’Connor, C.; Sketch, M.H. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2013, 2, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Lin, E.H.; Kroenke, K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2007, 29, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Female (n = 2201) | Male (n = 1551) | Total (n = 3752) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 52 ± 8.2 | 52 ± 8.0 | 52 ± 8.1 | 0.19 |

| Rural areas | 1438 (65.3) | 1071 (69.1) | 2509 (66.9) | 0.02 |

| Marital status: | ||||

| Married | 1917 (87.1) | 1383 (89.2) | 3300 (88.0) | <0.001 |

| Single (bachelor/bachelorette) | 125 (5.7) | 147 (9.5) | 272 (7.2) | |

| Widow/widower | 159 (7.2) | 21 (1.4) | 180 (4.8) | |

| Education: | ||||

| Primary | 223 (10.1) | 190 (12.3) | 413 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Vocation | 667 (30.3) | 723 (46.6) | 1390 (37.0) | |

| Secondary | 776 (35.3) | 428 (27.6) | 1204 (32.1) | |

| University | 535 (24.3) | 210 (13.5) | 745 (19.9) | |

| Smoking status: | ||||

| Yes | 250 (11.4) | 345 (22.2) | 595 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 1951 (88.6) | 1206 (77.8) | 3157 (84.1) | |

| Alcohol consumption: | ||||

| No or less than once a month | 2140 (97.2) | 1205 (77.7) | 3345 (89.2) | <0.001 |

| Between once a month and once a week | 42 (1.9) | 195 (12.6) | 237 (6.3) | |

| More than once a week | 19 (0.9) | 151 (9.7) | 170 (4.5) | |

| Lives alone | 116 (5.3) | 58 (3.7) | 174 (6.64) | 0.03 |

| BMI [kg/m2]: | ||||

| Normal [18.5–24.99 kg/m2] | 633 (28.9) | 272 (17.6) | 905 (24.2) | <0.001 |

| Overweight [25–29.99 kg/m2] | 794 (36.3) | 716 (46.3) | 1510 (40.4) | |

| Obesity [≥30 kg/m2] | 762 (34.8) | 560 (36.2) | 1322 (35.4) | |

| Comorbidities (Yes) # | 661 (30.0) | 427 (27.5) | 1088 (29) | 0.09 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): | ||||

| Total score | 6.9 ± 3.5 | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 6.4 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| None (0–4) | 574 (26.1) | 579 (37.5) | 1153 (30.7) | <0.01 |

| Mild (5–9) | 1196 (54.3) | 798 (51.5) | 1994 (53.1) | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 366 (16.6) | 150 (9.7) | 516 (13.8) | |

| Moderately-Severe (15–19) | 19 (1.2) | 51 (2.3) | 70 (1.9) | |

| Severe (20–27) | 5 (0.36) | 14 (0.64) | 19 (0.55) | |

| PHQ-9 (≥10) | 431 (19.6) | 174 (11.2) | 605 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 2201) | p | Male (n = 1551) | p | |||

| 0–9 | ≥10 | 0–9 | ≥10 | |||

| Age [years]: | 51 ± 8.3 | 53 ± 7.6 | <0.001 | 52 ± 8 | 54 ± 7.9 | 0.002 |

| Place of living: | ||||||

| Rural areas | 1133 (78.8) | 305 (21.2) | 0.008 | 947 (88.4%) | 124 (11.6) | 0.5 |

| Urban areas | 637 (83.5) | 126 (16.5) | 430 (89.6%) | 50 (10.4) | ||

| Marital status: | ||||||

| Married | 1550 (80.9) | 367 (19.1) | 0.38 | 1239 (89.6%) | 144 (10.4) | 0.03 |

| Single (bachelor/bachelorette) | 98 (78.4) | 27 (21.6) | 121 (82.3%) | 26 (17.7) | ||

| Widow/widower | 122 (76.7) | 37 (23.3) | 17 (81%) | 4 (19) | ||

| Education: | ||||||

| Primary | 162 (72.6) | 61 (27.4) | <0.001 | 155 (81.6) | 35 (18.4) | 0.002 |

| Vocation | 522 (78.3) | 145 (21.7) | 638 (88.2) | 85 (11.8) | ||

| Secondary | 626 (80.7) | 150 (19.3) | 394 (92.1) | 34 (7.9) | ||

| University | 460 (86) | 75 (14) | 190 (90.5) | 20 (9.5) | ||

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Yes | 194 (77.6) | 56 (22.4) | 0.23 | 287 (83.2) | 58 (16.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 1576 (80.8) | 375 (19.2) | 1090 (90.4) | 116 (9.63) | ||

| Alcohol consumption: | ||||||

| No or less than once a month | 1718 (80.3) | 422 (19.7) | 0.21 | 1075 (89.2) | 130 (10.8) | 0.16 |

| Between once a month and once a week | 38 (90.5) | 4 (9.5) | 175 (89.7) | 20 (10.3) | ||

| More than once a week | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 127 (84.1) | 24 (15.9) | ||

| Lives alone | ||||||

| Yes | 79 (68.1) | 37 (31.9) | 0.001 | 43 (74.1) | 15 (25.9) | 0.001 |

| No | 1691 (81.1) | 394 (18.9) | 1334 (89.4) | 159 (10.6) | ||

| BMI [kg/m2]: | ||||||

| Norm [18.5–24.99 kg/m2] | 536 (84.7) | 97 (15.3) | <0.001 | 240 (88.2) | 32 (11.8) | 0.86 |

| Overweight [25–29.99 kg/m2] | 641 (80.7) | 153 (19.3) | 639 (89.2) | 77 (10.8) | ||

| Obese [≥30 kg/m2] | 584 (76.6) | 178 (23.4) | 495 (88.4) | 65 (11.6) | ||

| Comorbidities # | ||||||

| Yes | 500 (75.6) | 161 (24.4) | <0.001 | 355 (83.1) | 72 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 1270 (82.5) | 270 (17.5) | 1022 (90.9) | 102 (9.1) | ||

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female: | |||

| Place of living: | |||

| Urban areas | 1 | ||

| Rural areas | 1.206 | 1.005–1.448 | 0.044 |

| Education: | |||

| Primary | 1 | ||

| Vocation | 0.982 | 0.730–1.321 | 0.903 |

| Secondary | 1.058 | 0.787–1.422 | 0.710 |

| University | 0.691 | 0.505–0.944 | 0.02 |

| Lives alone: | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.731 | 1.204–2.448 | 0.003 |

| BMI [kg/m2]: | |||

| Norm [18.5–24.99 kg/m2] | 1 | ||

| Overweight [25–29.99 kg/m2] | 1.200 | 0.977–1.474 | 0.081 |

| Obesity [≥30 kg/m2] | 1.407 | 1.127–1.756 | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities: # | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.264 | 1.046–1.529 | 0.015 |

| Male: | |||

| Age: | 1.022 | 1.035–1.035 | 0.001 |

| Education: | |||

| Primary | 1 | ||

| Vocation | 0.804 | 0.588–1.099 | 0.172 |

| Secondary | 0.658 | 0.470–0.923 | 0.015 |

| University | 0.747 | 0.503–1.109 | 0.148 |

| Smoking status: | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.546 | 1.218–1.961 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption: | |||

| No or less than once a month | 1 | ||

| Between once a month and once a week | 1.296 | 0.966–1.740 | 0.084 |

| More than once a week | 1.656 | 1.187–2.311 | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities: # | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.431 | 1.42–1.794 | 0.002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polak, M.; Nowicki, G.J.; Naylor, K.; Piekarski, R.; Ślusarska, B. The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms and Their Socioeconomic and Health Predictors in a Local Community with a High Deprivation: A Cross-Sectional Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811797

Polak M, Nowicki GJ, Naylor K, Piekarski R, Ślusarska B. The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms and Their Socioeconomic and Health Predictors in a Local Community with a High Deprivation: A Cross-Sectional Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811797

Chicago/Turabian StylePolak, Maciej, Grzegorz Józef Nowicki, Katarzyna Naylor, Robert Piekarski, and Barbara Ślusarska. 2022. "The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms and Their Socioeconomic and Health Predictors in a Local Community with a High Deprivation: A Cross-Sectional Studies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811797

APA StylePolak, M., Nowicki, G. J., Naylor, K., Piekarski, R., & Ślusarska, B. (2022). The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms and Their Socioeconomic and Health Predictors in a Local Community with a High Deprivation: A Cross-Sectional Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811797