Is There a Missing Link? Exploring the Effects of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance in the Chinese Construction Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

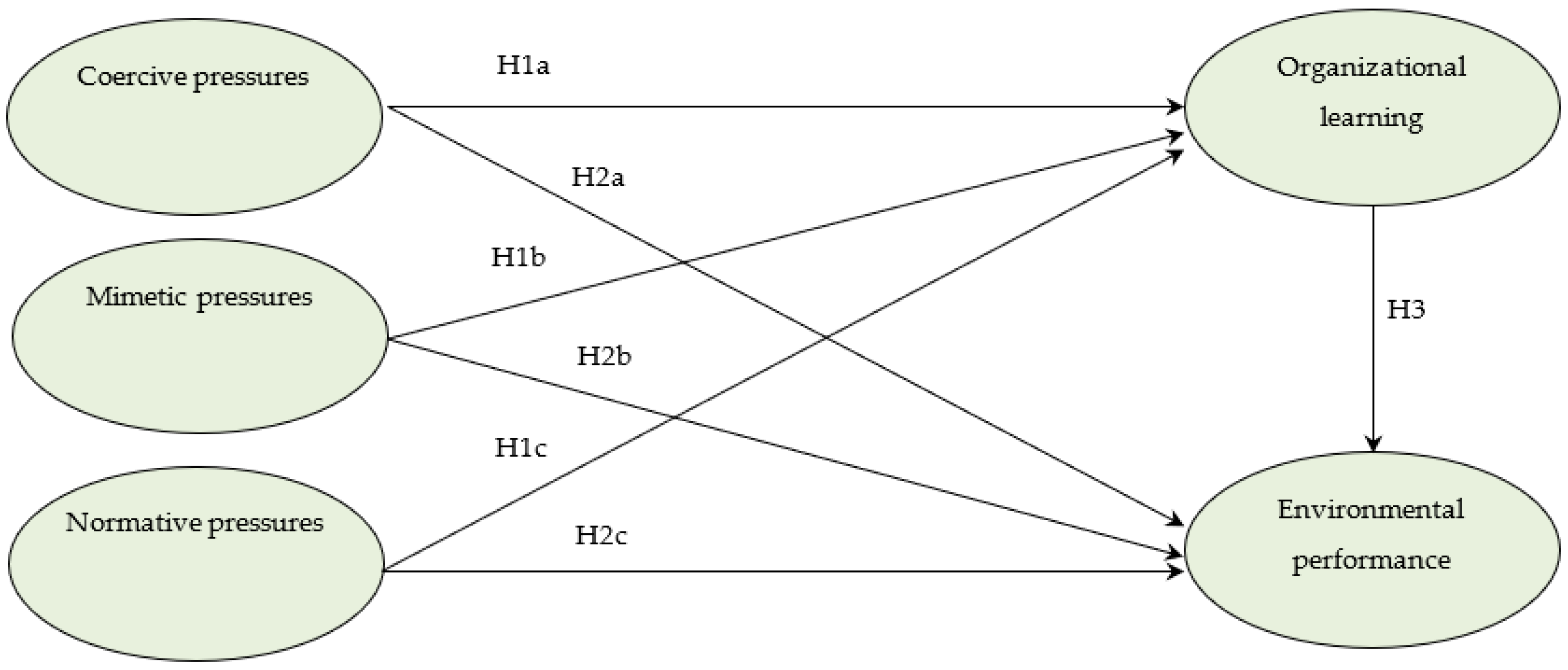

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Institutional Theory

2.2. Organizational Learning Theory

2.3. Research Hypotheses

2.3.1. The Influence of Institutional Pressures on Organizational Learning

2.3.2. The Influence of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance

2.3.3. The Influence of Organizational Learning on Environmental Performance

2.3.4. The Mediation role of Organizational Learning

3. Research Method

3.1. Study Setting and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measure Validation

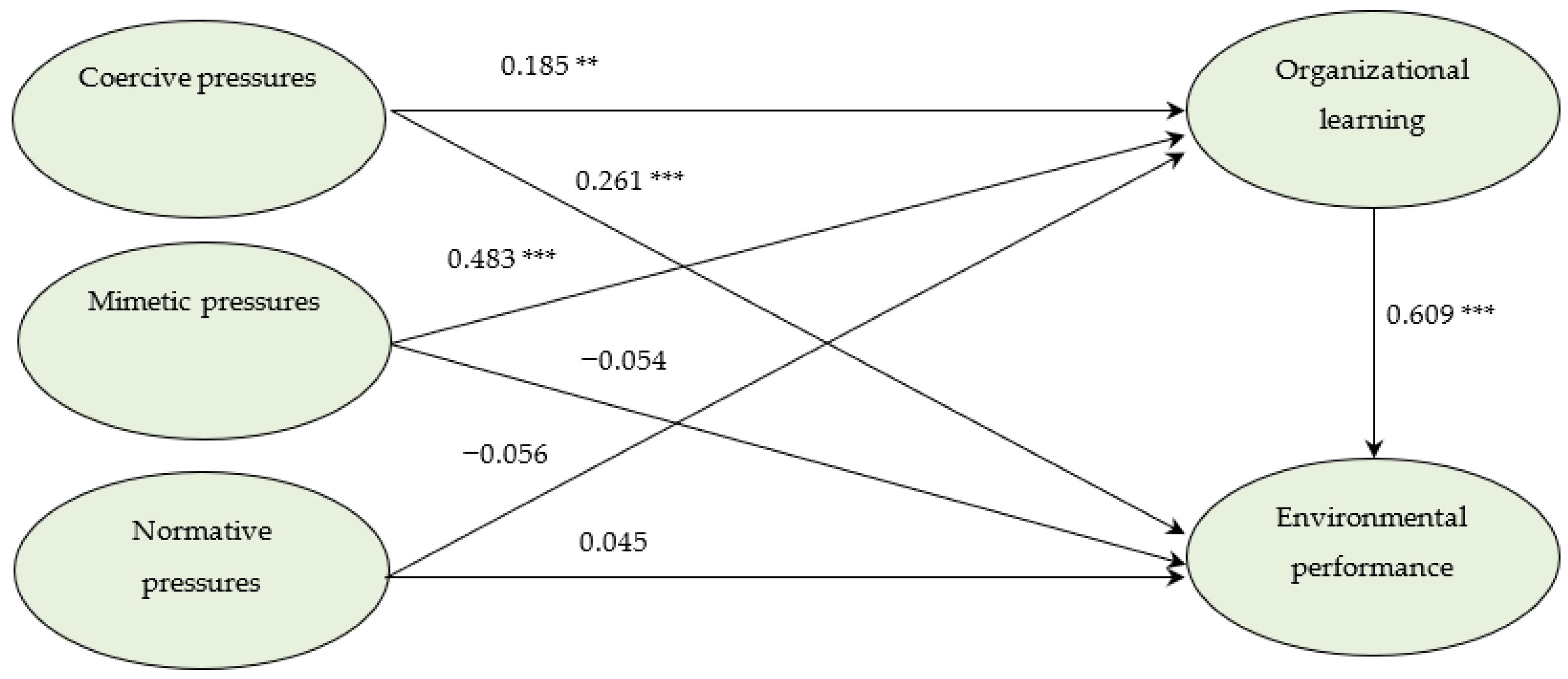

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Testing the Mediation Effects

5. Discussions and Implications

5.1. Summary of the Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Constructs and Measurement Items

| Constructs | Lable | Questionnaire Items | Sources |

| Environmental performance | EP1 | Our company has reduced the use of hazardous/toxic materials in construction projects. | Vanalle et al. [15], Simpson [30], and Dubey et al. [34] |

| EP2 | Our company has reduced environmental accidents and health hazards in construction projects. | ||

| EP3 | Our company has reduced the waste water and solid wastes in construction projects. | ||

| EP4 | Our company has reduced the consumption of electricity and water in construction projects. | ||

| EP5 | Our company has used low-pollution and eco-friendly materials in construction projects. | ||

| EP6 | Our company has reduced material waste. | ||

| Coercive Pressures | CP1 | The central/local government has set strict environmental standards which our company needs to comply with. | Juárez-Luis et al. [20], Gunarathne et al. [32], Dubey et al. [34]. |

| CP2 | Violation of relevant environmental regulations will be severely punished. | ||

| CP3 | Government regulations provide clear guidelines in controlling pollution level in construction industry. | ||

| CP4 | The central/local government strictly monitors the pollution level of construction companies on a periodic basis. | ||

| Mimetic Pressures | MP1 | The leading companies in our sector set an example for environmentally responsible practices. | Juárez-Luis et al. [20], Dubey et al. [34] and Daddi et al. [60] |

| MP2 | The leading companies in our sector are known for their practices that promoted environmental preservation. | ||

| MP3 | The leading companies in our sector are known for their practices that promoted environmental preservation. | ||

| MP4 | The leading companies in our industry are intending to reduce their impacts on the environment. | ||

| Normative Pressure | NP1 | The increasing environmental consciousness of consumers has spurred our company to reduce environmental pollution. | Juárez-Luis et al. [15] and Daddi et al. [60] |

| NP2 | Consumers have developed a preference for eco-friendly buildings. | ||

| NP3 | Most consumers are very concerned about our environmental behavior. | ||

| NP4 | Industry associations have used professional means to get companies to focus on environmental protection. | ||

| Organizational learning | OL1 | Our company proactively searches for advanced construction technologies (e.g., assembled building technology, BIM) that would reduce waste. | Bhatia and Jakhar [69], Tu and Wu [27], Cui and Wang [48] |

| OL2 | Our company proactively promotes the implementation of clean production processes and technologies in construction projects. | ||

| OL3 | Our company proactively searches for information to refine common methods and ideas in solving problems in construction projects. | ||

| OL4 | Our company focuses on continuous improvement by proactively adopting total quality management in construction. | ||

| OL5 | Our company focuses on pollution prevention by proactively adopting environmental management systems. | ||

| OL6 | Our company proactively applies the certification of Occupational Health and Safety Management System (ISO 45001) and/or environmental management system(ISO 14001). | ||

| OL7 | Our company changes the existing high energy-consumption technology and switches to energy-saving and environmental protection technology. | ||

| OL8 | Our company proactively learns through feedback from previous construction projects, rather than merely reacting to the detected issues. |

References

- Roome, N.; Wijen, F. Stakeholder power and organizational learning in corporate environmental management. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E. Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Montiel, I. When are corporate environmental policies a form of green-washing? Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 377–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implication. J. Bus. Ethics. 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Harrison, N.S. Organizational design and environmental performance clues from the electronics industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1993, 4, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, A.; Kildegaard, A. Clean technological change in developing-country industrial clusters: Mexican leather tanning. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2010, 12, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Stakeholder pressures and environmental performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Wang, Y.; Saeed, M.R. Net-zero emission targets and the role of managerial environmental awareness, customer pressure, and regulatory control toward environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4223–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Adenso-Diaz, B. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.H.; Ho, Y.L. Institutional pressures and environmental performance in the global automotive industry: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Internationalization and environmentally-related organizational learning among Chinese manufacturers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, C.T. Exploring institutional pressures, firm green slack, green product innovation and green new product success: Evidence from Taiwan’s high-tech industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanalle, R.M.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Filho, M.G.; Lucato, W.C. Green supply chain management: An investigation of pressures, practices, and performance within the Brazilian automotive supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Jun, Y.; Nubuor, S.A.; Priyankara, H.P.R.; Jayasuriya, M.P.F. Institutional pressures, green supply chain management practices on environmental and economic performance: A two theory view. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Cordeiro, J.; Sarkis, J. Institutional pressures, dynamic capabilities and environmental management systems: Investigating the ISO 9000—Environmental management system implementation linkage. J Environ Manag. 2013, 114, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Enhancing corporate sustainable development: Stakeholder pressures, organizational learning, and green innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhao, X.; Prahinski, C.; Li, Y. The impact of institutional pressures, top managers posture and reverse logistics on firm performance—Evidence from China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Luis, G.; Sánchez-Medina, P.S.; Díaz-Pichardo, R. Institutional pressures and green practices in small agricultural businesses in Mexico: The mediating effect of farmers’ environmental concern. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Linking organizational and field level analyses: The diffusion of corporate environmental practice. Organ. Environ. 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.X.; Hu, Z.P.; Liu, C.S.; Yu, D.J.; Yu, L.F. The relationships between regulatory and customer pressure, green organizational responses, and green innovation performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Ellinger, A.D. Organizational learning: Perception of external environment and innovation performance. Int. J. Manpower. 2011, 32, 512–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, A.D. Adopting the environmental jolts. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1982, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Manzanares, A.; Aragon-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. The influence of stakeholders on the environmental strategy of service firms: Rhe moderating effects of complexity, uncertainty and munificence. Brit. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van Der Linde, C. Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis, J.; Dijkshoorn, J. Relationships between solid waste management performance and environmental practice adoption in Welsh SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4989–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D. Knowledge resources as a mediator of the relationship between recycling pressures and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gunarathne, A.D.N.; Lee, K.-H.; Kaluarachchilage, P.K.H. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the relationship between leadership, operational practices, institutional pressures and environmental performance: A framework for green supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.H.; Lai, K.H. Mediating effect of managers’ environmental concern: Bridge between external pressures and firms’ practices of energy conservation in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.; Yasir, M.; Yasir, M.; Javed, A. Nexus of institutional pressures, environmentally friendly business strategies, and environmental performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.J.; Whitwell, G.J.; Lukas, B.A. Schools of thought in organizational learning. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Peon, J.M.; Ordas, C.J. Organizational learning as a determining factor in business performance. Learn. Organ. 2005, 12, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Ramdom House: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Browne, G.J.; Li, D. Adoption of building information modeling in Chinese construction industry: The technology-organization-environment framework. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 1878–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, B.; Arnold, M. Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoof, B.V. Organizational learning in cleaner production among Mexican supply networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.D.; Irani, Z.; Edwards, D. Learning to reduce rework in projects: Analysis of firms learning and quality practices. Proj. Manag. J. 2002, 34, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.H. Organizational learning, absorptive capacity, imitation and innovation: Empirical analyses of 115 firms across China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2015, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upstill-Goddard, J.; Glass, J.; Dainty, A.; Nicholson, I. Implementing sustainability in small and medium-sized construction firms: The role of absorptive capacity. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2016, 23, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G. The performance effect of organizational learning and market orientation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Wang, J. Shaping sustainable development: External environmental pressure, exploratory green learning, and radical green innovation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 29, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M. Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J. Untangling the effects of overexploration and overexploitation on organizational performance: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 925–951. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.W.Y.; Lai, K.H.; Teo, T.S.H. Institutional pressures and mindful its management: The case of a container terminal in China. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, J. Do Social Movements Matter to Organizations? An Institutional Perspective on Corporate Responses to the Contemporary Environmental Movement. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Zuo, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.Y. Key factors for the BIM adoption by architects: A China study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2015, 22, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A. Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the US chemical industry. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Christmann, P.; Taylor, G. Globalization and the environment: Determinants of firm self-regulation in China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, S.; Fernie, S. Organizational learning in construction supply chains. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2013, 20, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.E.; Elsaay, H. A learning-based framework adopting post occupancy evaluation for improving the performance of architectural design firms. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2018, 16, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghimien, D.O.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Oke, A.E. Critical success factors for digital partnering of construction organisations—A delphi study. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2020, 27, 3171–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi, T.; Testa, F.; Frey, M.; Iraldo, F. Exploring the link between institutional pressures and environmental management systems effectiveness: An empirical study. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Seidl, D. Managing Legitimacy in Complex and Heterogeneous Environments: Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, B.; March, J.G. Organizational learning. Annu. Rev. Soc. 1988, 14, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A.; Arif, M.; Younus, M. Exploring firm performance by institutional pressures driven green supply chain management practices. Smart Sustain. Built. 2019, 8, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.G. Change in the presence of residual fit: Can competing frames coexist? Organ. Sci. 2016, 17, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Jakhar, S.K. The effect of environmental regulations, top management commitment and organizational learning on green product innovation: Evidence from automobile industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3907–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Baird, K. The comprehensiveness of environmental management systems: The influence of institutional pressures and the impact on environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Stern, L.W.; Anderson, J.C. Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 1633–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Handbook of Organizational Measurement; Pitman Publishing: Marshfield, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NK, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods. 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, W.; Zhao, M. A study on the impact of institutional pressure on carbon information disclosure: The mediating effect of enterprise peer influence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seles, B.M.R.P.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Dangelico, R.M. The green bullwhip effect, the diffusion of green supply chain practices, and institutional pressures: Evidence from the automotive sector. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; McManus, S.E. Methodological fit in management field research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1155–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, P.; Dentoni, D. Learning from stakeholder pressure and embeddedness: The roles of absorptive capacity in the corporate social responsibility of Dutch agribusinesses. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Mean | Standard Deviation | CORPRE | MIMPRE | NORPRE | ORGLER | ENVPER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORPRE | 4.2285 | 0.45567 | 0.527 | ||||

| MIMPRE | 3.8797 | 0.50301 | 0.146 * | 0.508 | |||

| NORPRE | 3.6091 | 0.70444 | 0.112 | 0.141 * | 0.549 | ||

| ORGLER | 4.2094 | 0.46336 | 0.226 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.043 | 0.517 | |

| ENVPER | 4.1959 | 0.45828 | 0.351 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.063 | 0.566 ** | 0.535 |

| Construct | Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | t-Value | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive pressures | CP1 | 0.794 a | -- | 0.812 | 0.728 |

| CP2 | 0.813 | 12.263 *** | |||

| CP3 | 0.616 | 9.199 *** | |||

| CP4 | 0.661 | 10.491 *** | |||

| Mimetic pressures | MP1 | 0.778 a | -- | 0.792 | 0.780 |

| MP2 | 0.576 | 8.792 *** | |||

| MP3 | 0.840 | 12.065 *** | |||

| MP4 | 0.625 | 9.642 *** | |||

| Normative pressures | NP1 | 0.841 a | -- | 0.821 | 0.783 |

| NP2 | 0.839 | 14.328 *** | |||

| NP3 | 0.692 | 11.39 *** | |||

| NP4 | 0.554 | 8.678 *** | |||

| Organizational learning | OL1 | 0.682 a | -- | 0.893 | 0.797 |

| OL2 | 0.590 | 8.918 *** | |||

| OL3 | 0.804 | 11.759 *** | |||

| OL4 | 0.710 | 10.492 *** | |||

| OL5 | 0.729 | 10.784 *** | |||

| OL6 | 0.772 | 11.287 *** | |||

| OL7 | 0.758 | 11.244 *** | |||

| OL8 | 0.685 | 10.232 *** | |||

| Environmental performance | EP1 | 0.721 a | -- | 0.873 | 0.758 |

| EP2 | 0.812 | 12.461 *** | |||

| EP3 | 0.688 | 10.584 *** | |||

| EP4 | 0.731 | 11.191 *** | |||

| EP5 | 0.734 | 11.222 *** | |||

| EP6 | 0.698 | 10.840 *** |

| Model Fit Index | Value in the Study | Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 1.944 | 1.0 < χ2/df < 3.0 |

| GFI | 0.857 | >0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.827 | >0.90 |

| RMR | 0.027 | <0.05 |

| RMSEA | 0.059 | <0.08 |

| PNFI | 0.747 | >0.50 |

| PGFI | 0.706 | >0.50 |

| CFI | 0.914 | >0.90 |

| IFI | 0.915 | >0.90 |

| Paths | Standardized Coefficient | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive pressures→Organizational learning | 0.185 ** | 2.791 | Supported |

| Mimetic pressures→Organizational learning | 0.483 *** | 6.327 | Supported |

| Normative pressures→Organizational learning | −0.056 | −0.892 | N.S. |

| Coercive pressures→Environmental performance | 0.261 *** | 4.134 | Supported |

| Mimetic pressures→Environmental performance | −0.054 | −0.761 | N.S. |

| Normative pressures→Environmental performance | 0.045 | 0.788 | N.S. |

| Organizational learning→Environmental performance | 0.609 *** | 6.976 | Supported |

| Coercive pressures→Organizational learning→Environmental performance | Supported | ||

| Mimetic pressures→Organizational learning→Environmental performance | Supported | ||

| Normative pressures→Organizational learning→Environmental performance | N.S. | ||

| Paths | Effect Type | Estimates | 95% CI | Mediating Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Mediating Variable | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Coercive pressure | Environmental performance | Organizational learning | Total effect | 0.374 | 0.223 | 0.504 | Partial |

| Direct effect | 0.261 | 0.128 | 0.385 | ||||

| Indirect effect | 0.113 | 0.028 | 0.189 | ||||

| Mimetic pressure | Total effect | 0.240 | 0.112 | 0.387 | Complete | ||

| Direct effect | −0.054 | −0.208 | 0.105 | ||||

| Indirect effect | 0.294 | 0.199 | 0.413 | ||||

| Normative pressure | Total effect | 0.011 | −0.100 | 0.128 | None | ||

| Direct effect | 0.045 | −0.046 | 0.150 | ||||

| Indirect effect | −0.034 | −0.115 | 0.041 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, D.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Nie, T.; Song, Z. Is There a Missing Link? Exploring the Effects of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance in the Chinese Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11787. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811787

Lee D, Fu Y, Zhou D, Nie T, Song Z. Is There a Missing Link? Exploring the Effects of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance in the Chinese Construction Industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11787. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811787

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Dongmei, Yuxia Fu, Daijiao Zhou, Tao Nie, and Zhihong Song. 2022. "Is There a Missing Link? Exploring the Effects of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance in the Chinese Construction Industry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11787. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811787

APA StyleLee, D., Fu, Y., Zhou, D., Nie, T., & Song, Z. (2022). Is There a Missing Link? Exploring the Effects of Institutional Pressures on Environmental Performance in the Chinese Construction Industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11787. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811787