The Association between New-Onset Depressive Symptoms and Participating in Medical Check-Ups among Elderly Individuals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Study Design

2.2. CES-D 10 Depressive Symptoms

2.3. Independent Variables and Other Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

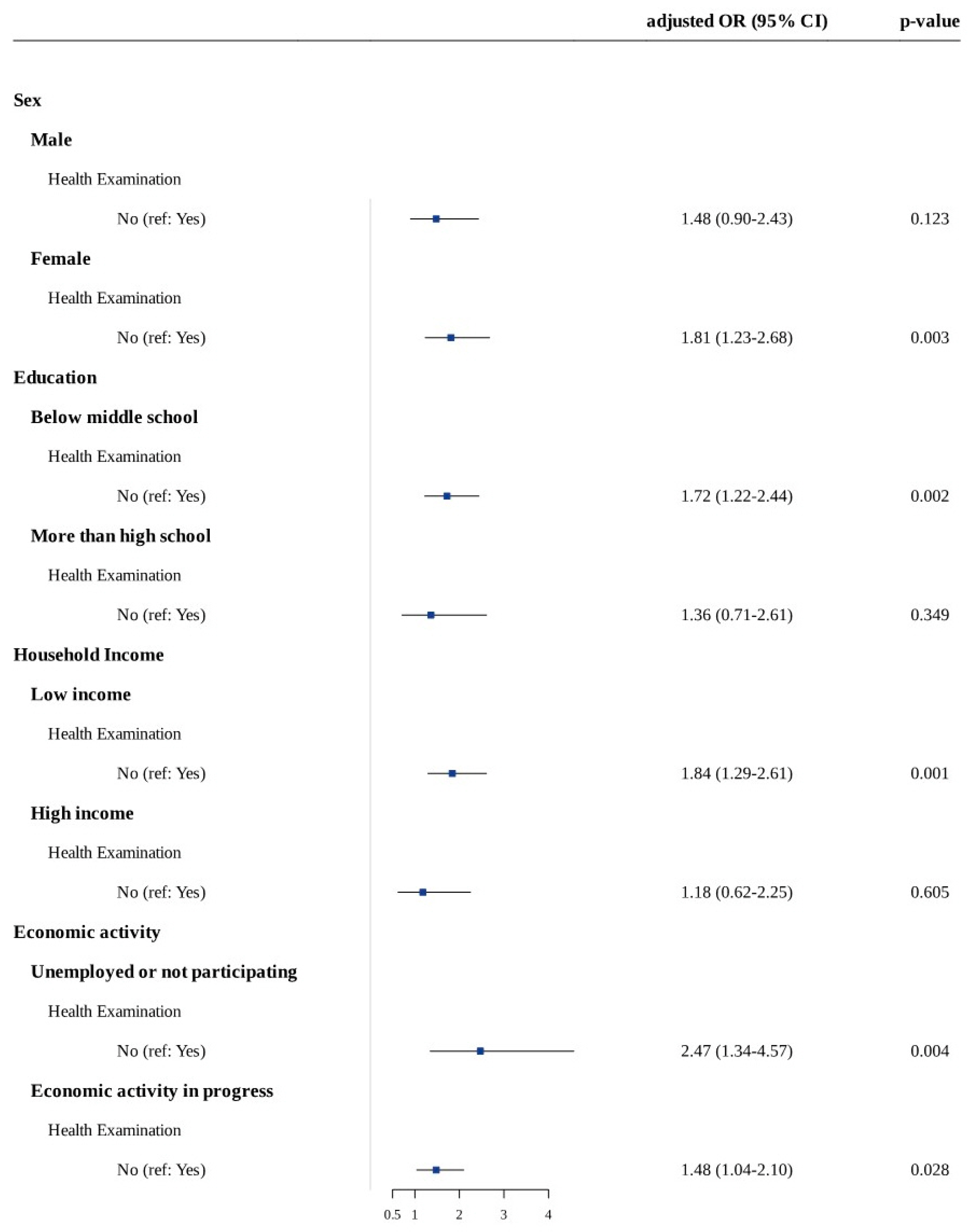

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lyu, J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, B. The WHO World Health Report 2001 on mental health. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2002, 11, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Yang, Q.; Sun, N.; Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, Y.; Lv, C.; Yin, X. Association between depression and the risk for fracture: A meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucciarelli, V.; Caterino, A.L.; Bianco, F.; Caputi, C.G.; Salerni, S.; Sciomer, S.; Maffei, S.; Gallina, S. Depression and cardiovascular disease: The deep blue sea of women’s heart. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.E.; Jo, M.-W.; Shin, Y.-W. Increased prevalence of depression in South Korea from 2002 to 2013. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zepeda, M.U.; Arango-Lopera, V.E.; Wagner, F.A.; Gallo, J.J.; Sánchez-García, S.; Juárez-Cedillo, T.; García-Peña, C. Factors associated with help-seeking behaviors in Mexican older individuals with depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.P.; Angst, F.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Rössler, W.; Angst, J. Treated versus non-treated subjects with depression from a 30-year cohort study: Prevalence and clinical covariates. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 266, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.H.; Chung, J.H.; Lee, S. Depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and healthcare utilization: Results from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA). Clin. Respir. J. 2021, 15, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, G.S.; Bruce, M.L. A model for intervention research in late-life depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfin, A. Depression: The benefits of early and appropriate treatment. Am. J. Manag. Care 2007, 13 (Suppl. 4), S92–S97. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.S.; Choe, E.Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.H.; Won, Y.J. Predictive costs in medical care for Koreans with metabolic syndrome from 2009 to 2013 based on the National Health Insurance claims dataset. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ihm, S.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, H.C. Status of hypertension screening in the Korea National General Health Screening Program: A questionnaire survey on 210 screening centers in two metropolitan areas. Clin. Hypertens. 2017, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Ko, C.Y.; Liu, J.P.; Lee, Y.L.; Chie, W.C. Nationwide periodic health examinations promote early treatment of hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia in adults: Experience from Taiwan. Public Health 2011, 125, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Franceschini, G.; Corsello, G.; Mestrovic, J.; Giardino, I.; Sacco, M.; Vural, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Pop, T.L. The Hikikomori Phenomenon of Social Withdrawal: An Emerging Condition Involving Youth’s Mental Health and Social Participation. J. Pediatr. 2020, 225, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohout, F.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Evans, D.A.; Cornoni-Huntley, J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J. Aging Health 1993, 5, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.; Artin, K.H.; Oxman, M.N. Screening for Depression in the Older Adult: Criterion Validity of the 10-Item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 1701–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Regular physical exercise and its association with depression: A population-based study short title: Exercise and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 309, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.; Kim, H. Social participation, health-related behavior, and depression of older adults living alone in Korea. Asian Soc. Work. Policy Rev. 2020, 14, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, J.; Kondo, K. Social factors relating to depression among older people in Japan: Analysis of longitudinal panel data from the AGES project. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.V.D.; Pivetta, N.R.S.; Oliveira, G.V.D.N.D.; Silva, D.A.D.; Nascimento, J.R.A.D.; Cavaglieri, C.R. Fatores intervenientes nos indicativos de depressão em idosos usuários das unidades básicas de saúde de Maringá, Paraná, 2017. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeleri, F.; Angeleri, V.A.; Foschi, N.; Giaquinto, S.; Nolfe, G. The influence of depression, social activity, and family stress on functional outcome after stroke. Stroke 1993, 24, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kino, S.; Jang, S.-N.; Kawachi, I. Healthy but unhappy? Cross-national comparative analysis of depressive symptoms in Japanese vs. Korean elders. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 95, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gilany, A.-H.; Elkhawaga, G.O.; Sarraf, B.B. Depression and its associated factors among elderly: A community-based study in Egypt. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 77, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Allen, J.; Alpass, F.; Stephens, C. Longitudinal Trajectories of Quality of Life and Depression by Housing Tenure Status. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 73, e165–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Chirwa, G.C. Economic Analysis of Inequality in Preventive Health Check-Ups Uptake in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 745356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, A.; Friis, K.; Osborne, R.H.; Maindal, H.T. National indicators of health literacy: Ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers—A population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Mu, Y. The Relationship Between Health Changes and Community Health Screening Participation Among Older People. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 870157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y.; Kang, H.T.; Lee, J.W.; Lim, H.J. The Association between Socioeconomic Status and Adherence to Health Check-up in Korean Adults, Based on the 2010–2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2018, 39, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebel, J.; Starker, A.; Jordan, S.; Richter, M.; Lampert, T. Determinants of health check attendance in adults: Findings from the cross-sectional German Health Update (GEDA) study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachey, U.; Ramlall, S.; Chipps, J. Depression in older adults: Prevalence and risk factors in a primary health care sample. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2017, 59, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Y.; Yoon, Y. Elderly road collision injury outcomes associated with seat positions and seatbelt use in a rapidly aging society—A case study in South Korea. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistics Korea. Statistics on the Aged. 2010. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/1/index.board (accessed on 30 May 2011).

- Shin, W.-S. Future Perspective of the Elderly Food in a Super-Aged Society. J. Korean Dysphagia Soc. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.T.; Na, H.R. Urology and Geriatrics in Korea: Present Status and Future Directions. Int. Neurourol. J. 2022, 26, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimmins, E.M. Lifespan and Healthspan: Past, Present, and Promise. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, W.; Park, E.-C.; Jang, S.-I. The Association Between the Changes in General, Family, and Financial Aspects of Quality of Life and Their Effects on Cognitive Function in an Elderly Population: The Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging, 2008–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Depressive Symptom (n = 313) | Non-Depressive Symptom (n = 3942) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 73.45 (7.9) | 71.17 (7.6) | |

| Sex | 0.327 | ||

| Men | 129 (41.2%) | 1744 (37.5%) | |

| Women | 184 (58.8%) | 2198 (62.5%) | |

| Education level | 0.004 | ||

| Middle school or below | 213 (68.1%) | 2393 (60.7%) | |

| High school or above | 100 (32.0%) | 1549 (39.3%) | |

| Smoking | 0.104 | ||

| Yes | 20 (6.4%) | 367 (9.3%) | |

| No | 293 (93.6%) | 3575 (90.7%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.116 | ||

| Yes | 86 (27.5%) | 1259 (31.9%) | |

| No | 227 (72.5%) | 2683 (68.1%) | |

| Participating medical check-up | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 245 (78.3%) | 3501 (88.1%) | |

| No | 68 (21.7%) | 441 (11.9%) | |

| Economic activity | <0.001 | ||

| Economic activity in progress | 79 (25.2%) | 1366 (34.7%) | |

| Unemployed or not participating | 234 (74.8%) | 2576 (65.4%) | |

| Physical activity (1 week) | 0.004 | ||

| 0 | 225 (71.9%) | 2503 (63.5%) | |

| ≤3 | 21 (6.7%) | 482 (12.2%) | |

| 4–5 | 30 (9.6%) | 508 (12.9%) | |

| ≥6 | 37 (11.8%) | 449 (11.4%) | |

| Household Income * | <0.001 | ||

| USD ≤ 19,014 | 159 (50.8%) | 1543 (39.1%) | |

| USD 19,014–34,236 | 76 (25.2%) | 1197 (30.4%) | |

| USD > 34,236 | 78 (24.9%) | 1202 (30.5%) | |

| Human relationship | <0.001 | ||

| Often | 208 (66.5%) | 3376 (85.6%) | |

| Rare | 105 (33.6%) | 566 (14.4%) | |

| Residence home ownership | <0.001 | ||

| Owned | 239 (76.4%) | 3455 (87.7%) | |

| Not Owned | 74 (23.7%) | 487 (12.4%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 210 (67.1%) | 3020 (76.6%) | |

| No | 103 (32.9%) | 922 (23.4%) |

| Variable | Participating MC (n = 3746) | Non-Participating MC (n = 509) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 70.90 (7.5) | 74.56 (8.2) | |

| Sex | 0.139 | ||

| Men | 1665 (44.5%) | 208 (40.9%) | |

| Women | 2081 (55.6%) | 301 (59.1%) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||

| Middle school or below | 2229 (59.5%) | 377 (74.1%) | |

| High school or above | 1517 (40.5%) | 132 (25.9%) | |

| Smoking | 0.178 | ||

| Yes | 332 (8.9%) | 55 (10.8%) | |

| No | 3414 (91.1%) | 454 (89.2%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1218 (32.5%) | 127 (25.0%) | |

| No | 2528 (67.5%) | 382 (75.1%) | |

| Economic activity | <0.001 | ||

| Economic activity in progress | 2436 (65.0%) | 374 (73.5%) | |

| Unemployed or not participating | 1310 (35.0%) | 135 (26.5%) | |

| Physical activity (1 week) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 2342 (62.5%) | 386 (75.8%) | |

| ≤3 | 459 (12.3%) | 44 (8.6%) | |

| 4–5 | 494 (13.2%) | 44 (8.6%) | |

| ≥6 | 451 (12.0%) | 35 (6.9%) | |

| Household Income * | <0.001 | ||

| USD ≤ 19,014 | 2213 (59.1%) | 352 (69.2%) | |

| USD 19,014–34,236 | 905 (24.2%) | 87 (17.1%) | |

| USD > 34,236 | 628 (16.8%) | 70 (13.8%) | |

| Human relationship | <0.001 | ||

| Often | 3112 (83.1%) | 472 (78.6%) | |

| Rare | 551 (16.9%) | 120 (21.4%) | |

| Residence home ownership | <0.001 | ||

| Owned | 3294 (87.9%) | 400 (78.6%) | |

| Not Owned | 452 (12.1%) | 109 (21.4%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2896 (77.3%) | 334 (65.6%) | |

| No | 850 (22.7%) | 175 (34.4%) |

| Variable | Values | Crude Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | CI | p | Odds Ratios | CI | p | Odds Ratios | CI | p | Odds Ratios | CI | p | ||

| Participating medical check-up | Yes | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||||||

| No | 2.2 | 1.65–2.93 | <0.001 | 1.95 | 1.46–2.61 | <0.001 | 1.84 | 1.34–2.53 | 0.001 | 1.65 | 1.22–2.24 | 0.001 | |

| Medical Check-Up | Socioeconomic Status | Final Model ¶ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | CI | p | ||

| Yes | High household income | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Low household income | 0.95 | 0.71–1.28 | 0.75 | |

| No | High household income | 1.21 | 0.65–2.25 | 0.55 |

| Low household income | 1.78 | 1.18–2.67 | 0.006 | |

| Yes | High education | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Low education | 1.09 | 0.80–1.49 | 0.57 | |

| No | High education | 1.43 | 0.76–2.69 | 0.27 |

| Low education | 1.89 | 1.25–2.87 | 0.002 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, H.; Sim, J.; Oh, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.; Yun, B.; Yoon, J.-h. The Association between New-Onset Depressive Symptoms and Participating in Medical Check-Ups among Elderly Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811509

Park H, Sim J, Oh J, Lee J, Lee C, Kim Y, Yun B, Yoon J-h. The Association between New-Onset Depressive Symptoms and Participating in Medical Check-Ups among Elderly Individuals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811509

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Heejoo, Juho Sim, Juyeon Oh, Jongmin Lee, Chorom Lee, Yangwook Kim, Byungyoon Yun, and Jin-ha Yoon. 2022. "The Association between New-Onset Depressive Symptoms and Participating in Medical Check-Ups among Elderly Individuals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811509

APA StylePark, H., Sim, J., Oh, J., Lee, J., Lee, C., Kim, Y., Yun, B., & Yoon, J.-h. (2022). The Association between New-Onset Depressive Symptoms and Participating in Medical Check-Ups among Elderly Individuals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811509