Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

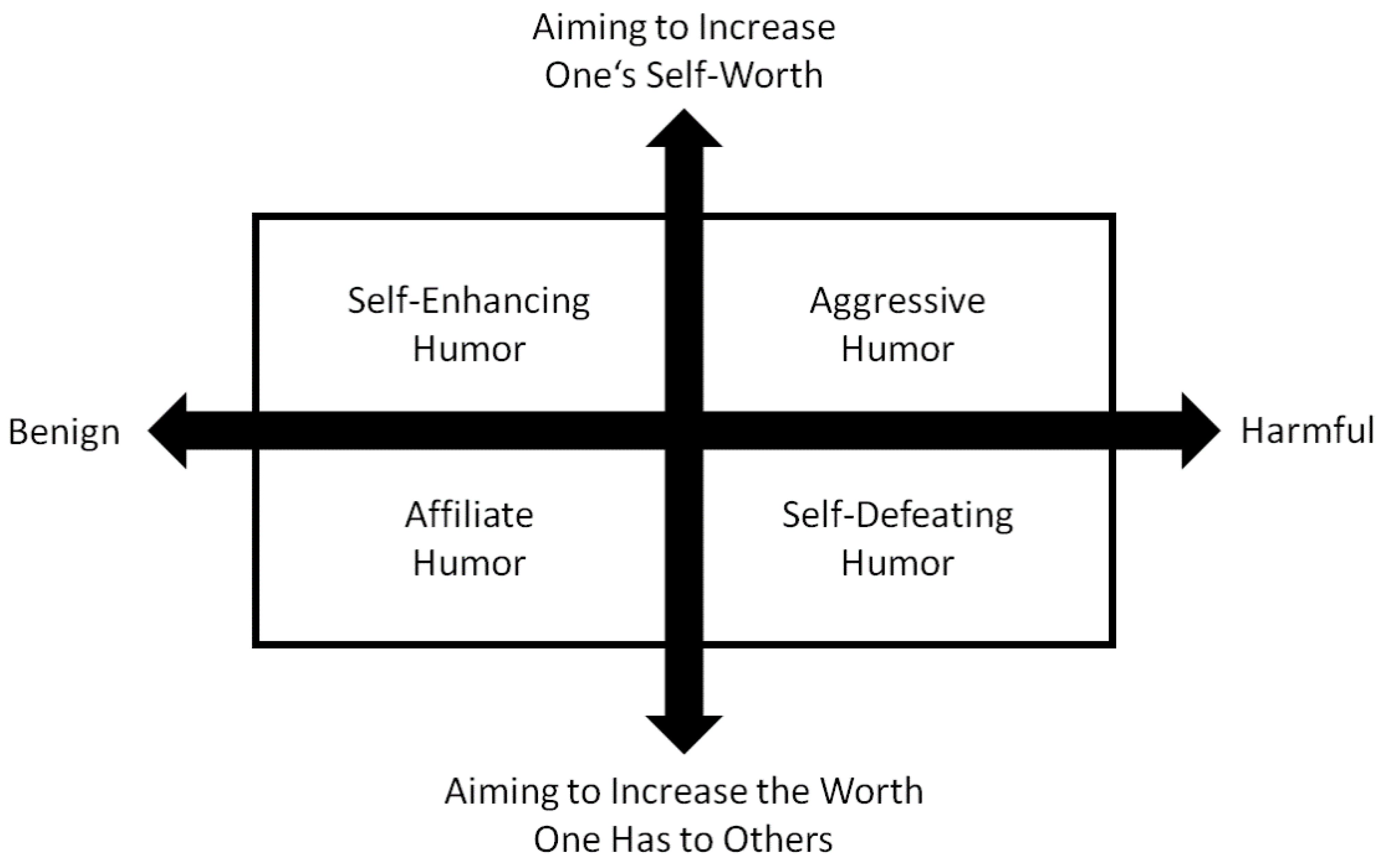

1.1. Humor Styles

1.2. School Bullying

1.3. Complementing Variable- with Person-Oriented Analyses

1.4. Short-Term Retrospective Measurement of Bullying-Related Behavior

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Use of Humor Styles

2.3.2. Use of Humor in Conflict Situations

2.3.3. Psychological School Adjustment

2.3.4. Bullying Victimization

2.4. Missing Data

2.5. Data Analytical Strategy

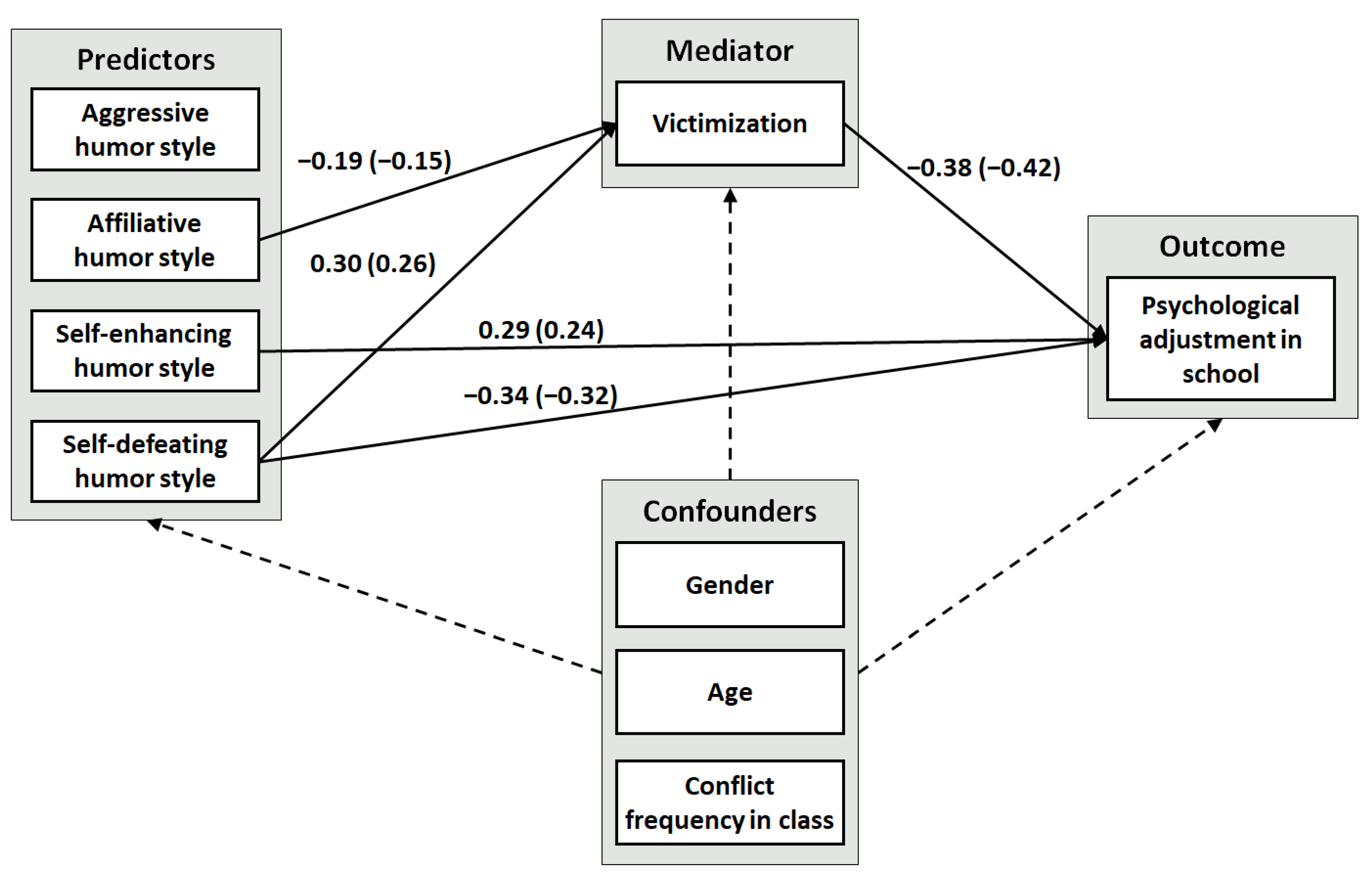

2.5.1. Mediation Analysis

2.5.2. Moderation Analysis

2.5.3. Determining Bullying-Related Groups

2.5.4. Differences between Bullying-Related Groups

2.5.5. Determining Latent Profiles of Humor-Related Groups

2.5.6. Differences between Humor-Related Latent Groups

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables

3.2. Mediation Model: Does Victimization Mediate the Effect of Humor Styles on School Adjustment?

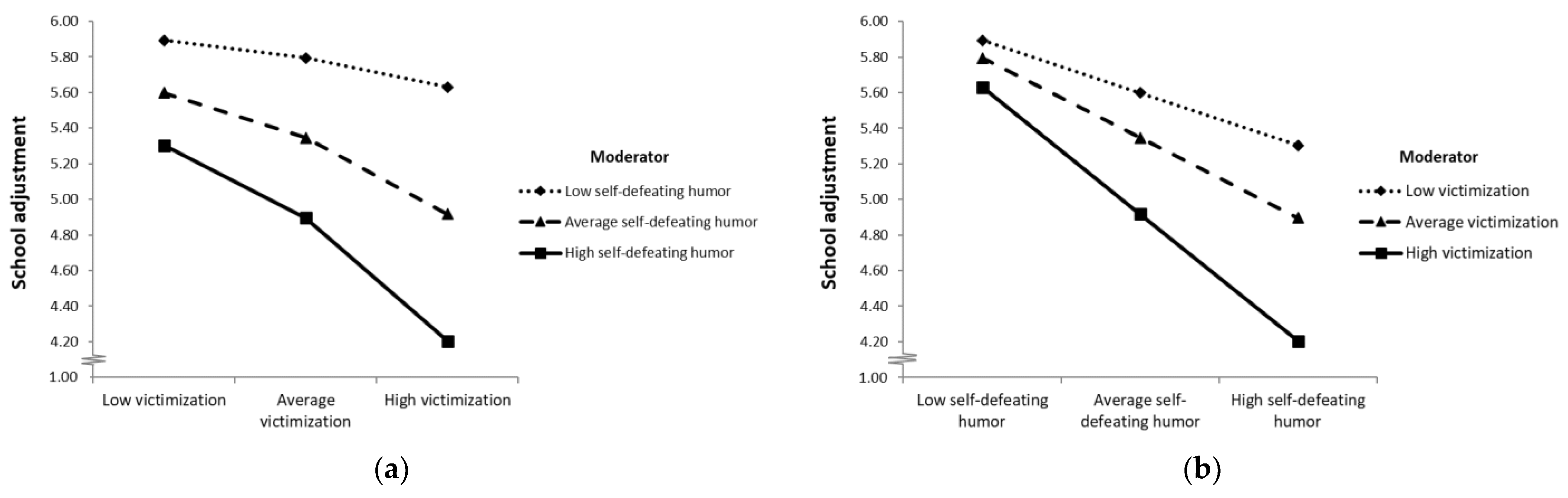

3.3. Moderation Model: Can Humor Styles Dampen or Strengthen the Negative Association between Victimization and School Adjustment?

3.4. Results Regarding Bullying-Related Groups

3.4.1. Determining Bullying-Related Group Membership

3.4.2. Bullying-Related Group Differences in Humor Styles

3.4.3. Bullying-Related Group Differences in Psychological School Adjustment

3.5. Results Regarding Humor-Related Latent Profile Groups

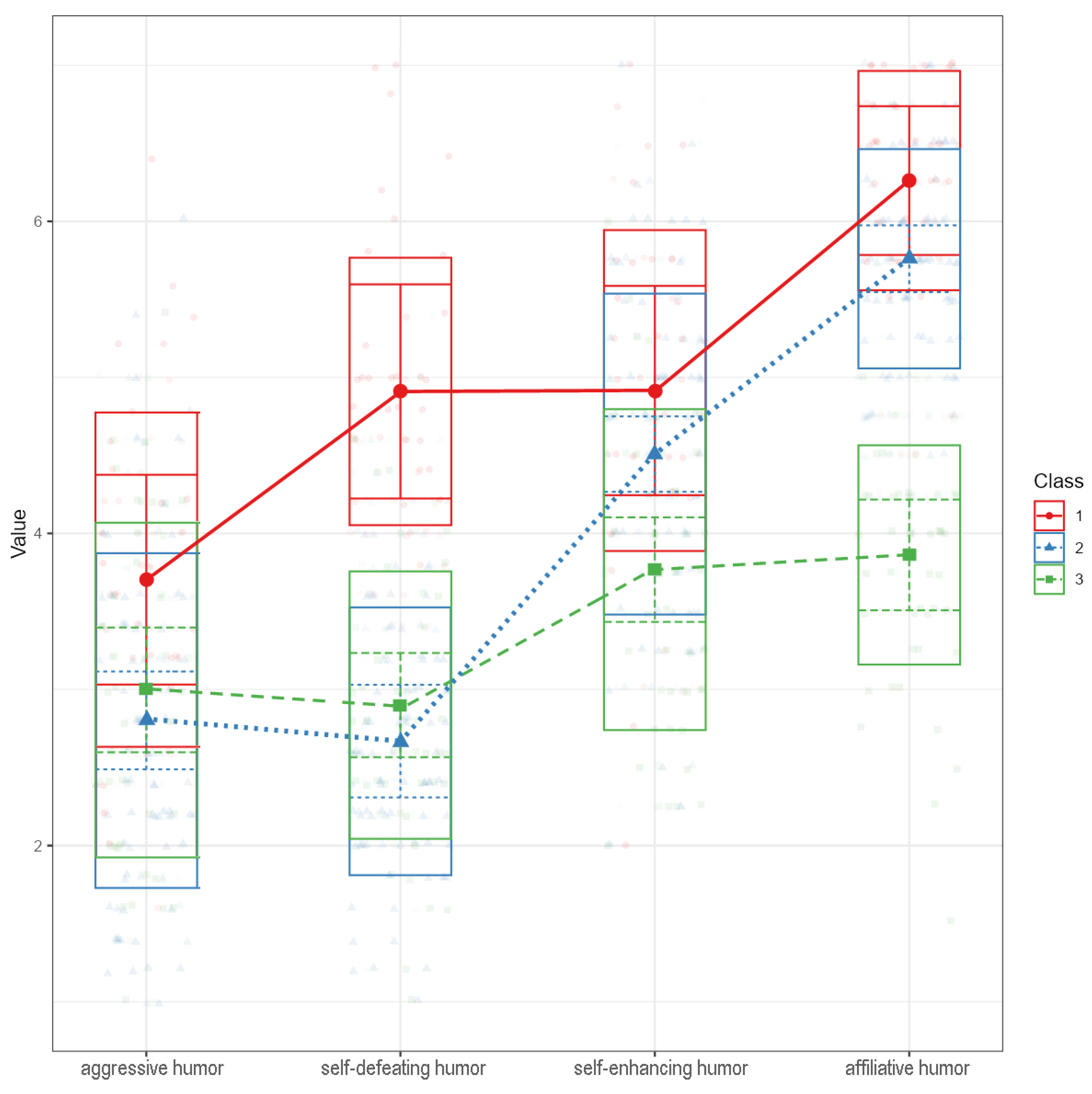

3.5.1. Determining Humor-Related Group Membership

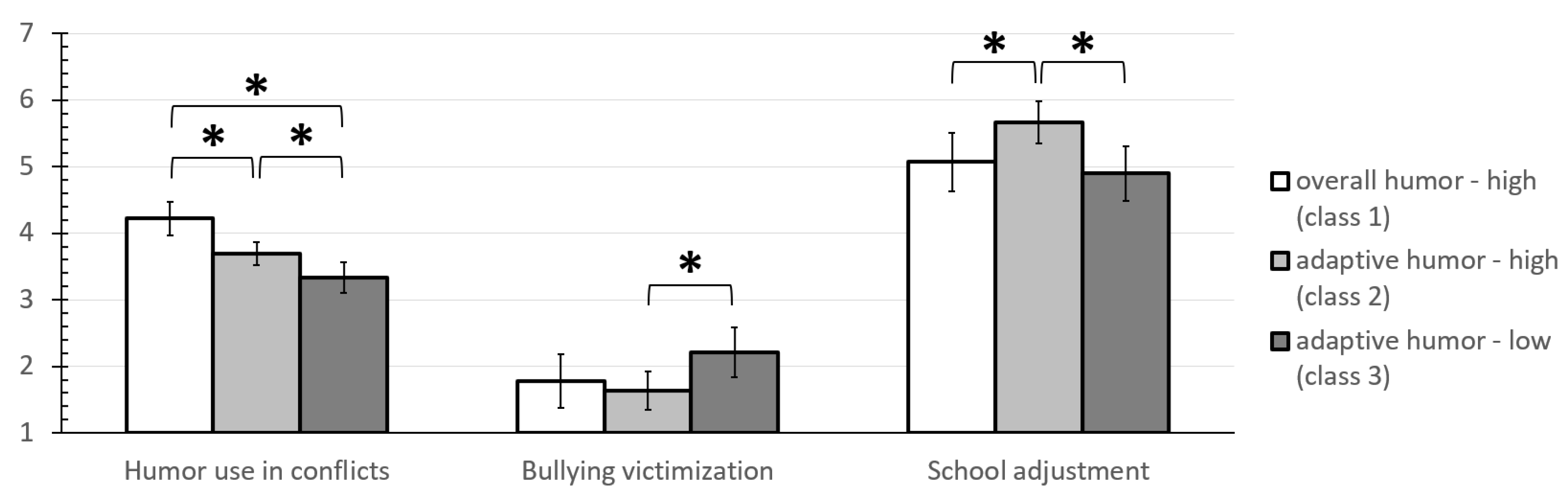

3.5.2. Humor-Related Group Differences in General Humor Use in Conflicts, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment

4. Discussion

4.1. Adverse Effects of Self-Defeating Humor

4.2. Beneficial Effects of Aggressive Humor

4.3. Beneficial Effects of Affiliative Humor Style

4.4. Beneficial Effects of Self-Enhancing Humor Style

4.5. Person-Oriented Group Comparisons

4.6. Practical Implications

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johansson, S.; Myrberg, E.; Toropova, A. School Bullying: Prevalence and Variation in and between School Systems in TIMSS 2015. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 74, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Bachmann, L. Perpetration and Victimization in Offline and Cyber Contexts: A Variable- and Person-Oriented Examination of Associations and Differences Regarding Domain-Specific Self-Esteem and School Adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerla, M. Humor Styles as Predictors of School Success and Self-Esteem. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291346406_Humor_Styles_as_Predictors_of_School_Success_and_Self-Esteem?channel=doi&linkId=56a14d3708ae24f62701fd88&showFulltext=true (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Kiuru, N.; Wang, M.-T.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Kannas, L.; Ahonen, T.; Hirvonen, R. Associations between Adolescents’ Interpersonal Relationships, School Well-Being, and Academic Achievement during Educational Transitions. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, D.M. The Thrill of Bullying: Bullying, Humour and the Making of Community. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2018, 48, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrick, N.R.; Spitz, A. The Interplay of Humor and Conflict in Conversation and Scripted Humorous Performance. Humor 2010, 23, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, N.; Rudolph, K.D.; Agoston, A.M. Depressive Symptoms Following Coping with Peer Aggression: The Moderating Role of Negative Emotionality. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dionigi, A.; Duradoni, M.; Vagnoli, L. Humor and the Dark Triad: Relationships among Narcissism, Machiavellianism, Psychopathy and Comic Styles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 197, 111766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A.; Puhlik-Doris, P.; Larsen, G.; Gray, J.; Weir, K. Individual Differences in Uses of Humor and Their Relation to Psychological Well-Being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. J. Res. Pers. 2003, 37, 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Lu, S.; Jiang, T.; Jia, H. Does the Relation between Humor Styles and Subjective Well-Being Vary across Culture and Age? A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Voracek, M.; Tran, U.S. “A Joke a Day Keeps the Doctor Away?” Meta-Analytical Evidence of Differential Associations of Habitual Humor Styles with Mental Health. Scand. J. Psychol. 2018, 59, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.N.; Kuiper, N.A. Humor Styles, Peer Relationships, and Bullying in Middle Childhood. Humor 2006, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A. Humor. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T.E.; Lappi, S.K.; O’Connor, E.C.; Banos, N.C. Manipulating Humor Styles: Engaging in Self-Enhancing Humor Reduces State Anxiety. Humor 2017, 30, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessen, C.Y.; Franken, F.R.; Ster, C.; Schmid, R.R.; Wolfmayr, C.; Mayer, A.-M.; Sobisch, M.; Kathofer, M.; Rattner, K.; Kotlyar, E.; et al. Humor Styles and Personality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Relations between Humor Styles and the Big Five Personality Traits. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 154, 109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-Y.; Park, K.-J. Self-Control and Sense of Humor as Moderating Factors for Negative Effects of Daily Hassles on School Adjustment for Children. Korean J. Child Stud. 2009, 30, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cann, A.; Collette, C. Sense of Humor, Stable Affect, and Psychological Well-Being. Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A.; Măirean, C. Not so Funny after All! Humor, Parents, Peers, and Their Link with Cyberbullying Experiences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 138, 107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Matson, C. Sense of Humor and Social Desirability: Understanding How Humor Styles Are Perceived. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2014, 66, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Marín, J.; Navarro-Carrillo, G.; Carretero-Dios, H. Is the Use of Humor Associated with Anger Management? The Assessment of Individual Differences in Humor Styles in Spain. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2018, 120, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, N.A.; Leite, C. Personality Impressions Associated with Four Distinct Humor Styles. Scand. J. Psychol. 2010, 51, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, N.A.; Klein, D.; Vertes, J.; Maiolino, N.B. Humor Styles and the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model of Generalized Anxiety. Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.L.; Hunter, S.C.; Jones, S.E. Children’s Humor Types and Psychosocial Adjustment. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 89, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.L.; Hunter, S.C.; Jones, S.E. Longitudinal Associations between Humor Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment in Adolescence. Eur. J. Psychol. 2016, 12, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stieger, S.; Formann, A.K.; Burger, C. Humor Styles and Their Relationship to Explicit and Implicit Self-Esteem. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2011, 50, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.A.; Fox, C.L. Longitudinal Associations between Younger Children’s Humour Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 36, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780631192411. [Google Scholar]

- Williford, A.; Fite, P.J.; Isen, D.; Poquiz, J. Associations between Peer Victimization and School Climate: The Impact of Form and the Moderating Role of Gender. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1301–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Exploring the Relationship between School Bullying and Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Students’ Sense of Belonging at School. Educ. Stud. 2022, 48, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, S.M.; Bennett, S.; Mazerolle, L. Bully Victimization, Truancy, and Violent Offending: Evidence from the ASEP Truancy Reduction Experiment. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2021, 19, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanek, E.; Strohmeier, D.; Yanagida, T. Depression in Groups of Bullies and Victims: Evidence for the Differential Importance of Peer Status, Reciprocal Friends, School Liking, Academic Self-Efficacy, School Motivation and Academic Achievement. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2017, 11, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Thornberg, R.; Flak, W.; Leśniewski, J. Downward Spiral of Bullying: Victimization Timeline from Former Victims’ Perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP10985–NP11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Spröber, N.; Bauman, S.; Rigby, K. How Teachers Respond to School Bullying: An Examination of Self-Reported Intervention Strategy Use, Moderator Effects, and Concurrent Use of Multiple Strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmatcheff, C.; Hénoumont, F.; Klée, E.; Galand, B. Stratégies et Réactions des Victimes et de Leur Entourage Face au Harcèlement Scolaire: Une Étude Rétrospective. Psychol. Française 2019, 64, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.A.; Romão, A.M. The Relation between Social Anxiety, Social Withdrawal and (Cyber)Bullying Roles: A Multilevel Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenty, S.; Bejerot, S.; Eriksson, K. Humor Style and Motor Skills: Understanding Vulnerability to Bullying. Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; James, L.; Fox, C.; Blunn, L. Laughing Together: The Relationships between Humor and Friendship in Childhood through to Adulthood. In Friendship in Cultural and Personality Psychology: International Perspectives; Altmann, T., Ed.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C.L.; Hunter, S.C.; Jones, S.E. The Relationship between Peer Victimization and Children’s Humor Styles: It’s No Laughing Matter! Soc. Dev. 2015, 24, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, C.L.; Jairam, D.; Davis, S.; Linkie, C.A.; Chatters, S.; Hodge, J.J. Effects of Students’ Grade Level, Gender, and Form of Bullying Victimization on Coping Strategy Effectiveness. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2020, 2, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, M.L.; Bauman, S.A.; Dinner, S.; Nixon, C.; Davis, S. An Investigation into How Students Respond to Being Victimized by Peer Aggression. J. Sch. Violence 2014, 13, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, D.F.; Mendonça, M.; Wolke, D.; Marturano, E.M.; Fontaine, A.M.; Coimbra, S. Resilience in the Face of Peer Victimization and Perceived Discrimination: The Role of Individual and Familial Factors. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 125, 105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, L.-G. The Crisis in Psychological Science and the Need for a Person-Oriented Approach. In Social Philosophy of Science for the Social Sciences; Valsiner, J., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G.D. Trajectories of Bullying Victimization and Perpetration in Australian School Children and Their Relationship to Future Delinquency and Conduct Problems. Psychol. Violence 2021, 11, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominic McCann, P.; Plummer, D.; Minichiello, V. Being the Butt of the Joke: Homophobic Humour, Male Identity, and Its Connection to Emotional and Physical Violence for Men. Health Sociol. Rev. 2010, 19, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, S.T.; Garandeau, C.F.; Badaly, D.; Duong, M.; Schwartz, D. Is Aggression Associated with Biased Perceptions of One’s Acceptance and Rejection in Adolescence? Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, X.; Salmivalli, C. Maladjustment of Bully-Victims: Validation with Three Identification Methods. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 1390–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, R.; Benbenishty, R. Perceptions of Teachers’ Support, Safety, and Absence from School Because of Fear among Victims, Bullies, and Bully-Victims. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2012, 82, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.R.; Johannes, N.; Winska, J.; Glinksa-Newes, A.; van Stekelenburg, A.; Nilsonne, G.; Dean, L.; Fido, D.; Galloway, G.; Jones, S.; et al. Exploring the Consistency and Value of Humour Style Profiles. Compr. Results Soc. Psychol. 2020, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasking, P.; Tatnell, R.C.; Martin, G. Adolescents’ Reactions to Participating in Ethically Sensitive Research: A Prospective Self-Report Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.J.; Harrington, K.V.; Neck, C.P. Resolving Conflict with Humor in a Diversity Context. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss-Sampson, M.A. Statistical Analysis in JASP 0.14: A Guide for Students. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Statistical-Analysis-in-JASP-A-Students-Guide-v14-Nov2020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Hayes, A.F.; Little, T.D. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kollerová, L.; Janošová, P.; Říčan, P. Good and Evil at School: Bullying and Moral Evaluation in Early Adolescence. J. Moral Educ. 2014, 43, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 2.2) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Seol, H. SnowRMM: Rasch Mixture Model for Jamovi. [Jamovi Module]. Available online: https://github.com/hyunsooseol/snowRMM (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Rosenberg, J.; Beymer, P.; Anderson, D.; Van Lissa, C.; Schmidt, J. Tidylpa: Easily Carry Out Latent Profile Analysis (Lpa) Using Open-Source or Commercial Software. [R Package]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=tidyLPA (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Greengross, G.; Miller, G.F. Dissing Oneself versus Dissing Rivals: Effects of Status, Personality, and Sex on the Short-Term and Long-Term Attractiveness of Self-Deprecating and Other-Deprecating Humor. Evol. Psychol. 2008, 6, 147470490800600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, N.A.; McHale, N. Humor Styles as Mediators between Self-Evaluative Standards and Psychological Well-Being. J. Psychol. 2009, 143, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.L.; Russek, L.N.; Dillon, M.M. Humor Use Moderates the Relation of Stressful Life Events with Psychological Distress. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.V. Was It Just Joke? Cyberbullying Perpetrations and Their Styles of Humor. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer, O.L.; Betts, L.R.; Baguley, T.; Binder, J.F. “I Feel like Everyone Does It”—Adolescents’ Perceptions and Awareness of the Association between Humour, Banter, and Cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.M.; Woods, H.A.; Bilz, L. Class Teachers’ Bullying-Related Self-Efficacy and Their Students’ Bullying Victimization, Bullying Perpetration, and Combined Victimization and Perpetration. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2022, 31, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, D.; Solomontos-Kountouri, O.; Burger, C.; Doğan, A. Cross-National Evaluation of the ViSC Social Competence Programme: Effects on Teachers. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, S.L.; Loizou, E. Research Connections and Implications for Practice to Further Support Young Children’s Humor. In Educating the Young Child; Loizou, E., Recchia, S.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, E.M.V. Blurred Lines: The Ambiguity of Disparaging Humour and Slurs in Norwegian High School Boys’ Friendship Groups. Young 2021, 29, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Kollerová, L. Teachers Can Make a Difference in Bullying: Effects of Teacher Interventions on Students’ Adoption of Bully, Victim, Bully-Victim or Defender Roles across Time. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzypiec, G.; Alinsug, E.; Amri Nasiruddin, U.; Andreou, E.; Brighi, A.; Didaskalou, E.; Guarini, A.; Heiman, T.; Kang, S.-W.; Kwon, S.; et al. Harmful Peer Aggression in Four World Regions: Relationship between Aggressed and Aggressor. J. Sch. Violence 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arënliu, A.; Strohmeier, D.; Konjufca, J.; Yanagida, T.; Burger, C. Empowering the Peer Group to Prevent School Bullying in Kosovo: Effectiveness of a Short and Ultra-Short Version of the ViSC Social Competence Program. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2020, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K.L. Hypotheses for Possible Iatrogenic Impacts of School Bullying Prevention Programs. Child Dev. Perspect. 2020, 14, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.A.; Fox, C.L. Humor Styles in Younger Children. In Educating the Young Child; Loizou, E., Recchia, S.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, J.L.; Fite, P.J.; Hoffman, L. Interactive Effects of Coping Strategies and Emotion Dysregulation on Risk for Peer Victimization. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 78, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, H.L.; White, S.J.; Chang, V.Y.; Juvonen, J. “Why Me?”: Characterological Self-Blame and Continued Victimization in the First Year of Middle School. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian Institute for Applied Telecommunications. Jugend-Internet-Monitor (Youth Internet Monitor). Available online: https://www.saferinternet.at/services/jugend-internet-monitor/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Paljakka, A.; Schwab, S.; Zurbriggen, C.L.A. Multi-Informant Assessment of Bullying in Austrian Schools. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 712381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01. Gender (0 = female) | 0.22 | — | — | |||||||||||

| 02. Age | 22.63 | 2.13 | −0.04 | — | ||||||||||

| 03. Class conflict frequency | 2.91 | 0.91 | 0.03 | −0.02 | — | |||||||||

| 04. Pure victim (0 = no) | 0.14 | — | 0.001 | −0.11 | 0.21 ** | — | ||||||||

| 05. Bully-victim (0 = no) | 0.12 | — | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.21 ** | −0.15 ‡ | — | |||||||

| 06. Victimization | 1.89 | 1.47 | −0.03 | −0.10 | 0.43 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.87 | ||||||

| 07. Aggressive humor | 3.06 | 1.13 | 0.21 ** | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.01 | 0.71 | |||||

| 08. Self-defeating humor | 3.23 | 1.25 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.27 *** | 0.12 | 0.22 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.75 | ||||

| 09. Self-enhancing humor | 4.39 | 1.11 | 0.03 | 0.16 * | −0.10 | −0.15 ‡ | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.62 | |||

| 10. Affiliative humor | 5.34 | 1.18 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.14 ‡ | −0.11 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.13 ‡ | 0.26 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.82 | ||

| 11. Humor use in conflicts | 3.68 | 0.80 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.001 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.25 ** | 0.32 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.68 | |

| 12. School adjustment | 5.24 | 1.34 | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.37 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.24 ** | −0.57 *** | −0.04 | −0.37 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.93 |

| 95% CI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Mediator | Outcome | Estimate | SE | z | p | Lower | Upper | Std (all) | Std (nox) |

| Total effects | ||||||||||

| Aggressive humor | — | School adjustment | 0.129 | 0.083 | 1.545 | 0.122 | −0.035 | 0.293 | 0.108 | 0.108 |

| Affiliative humor | — | School adjustment | 0.172 * | 0.080 | 2.161 | 0.031 | 0.016 | 0.328 | 0.151 | 0.151 |

| Self-enhancing humor | — | School adjustment | 0.301 *** | 0.084 | 3.578 | <0.001 | 0.136 | 0.467 | 0.252 | 0.252 |

| Self-defeating humor | — | School adjustment | −0.453 *** | 0.079 | −5.757 | <0.001 | −0.607 | −0.299 | −0.423 | −0.423 |

| Direct effects | ||||||||||

| Aggressive humor | — | School adjustment | 0.069 | 0.076 | 0.906 | 0.365 | −0.080 | 0.217 | 0.058 | 0.058 |

| Affiliative humor | — | School adjustment | 0.099 | 0.072 | 1.374 | 0.170 | −0.042 | 0.241 | 0.087 | 0.087 |

| Self-enhancing humor | — | School adjustment | 0.289 *** | 0.076 | 3.823 | <0.001 | 0.141 | 0.438 | 0.242 | 0.242 |

| Self-defeating humor | — | School adjustment | −0.338 *** | 0.073 | −4.641 | <0.001 | −0.481 | −0.196 | −0.316 | −0.316 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||||

| Aggressive humor | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.060 | 0.038 | 1.586 | 0.113 | −0.014 | 0.135 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

| Affiliative humor | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.073 * | 0.037 | 1.968 | 0.049 | 0.0003 | 0.145 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| Self-enhancing humor | Victimization | School adjustment | 0.012 | 0.037 | 0.326 | 0.744 | −0.061 | 0.085 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| Self-defeating humor | Victimization | School adjustment | −0.115 ** | 0.039 | −2.932 | 0.003 | −0.191 | −0.038 | −0.107 | −0.107 |

| Effect on School Adjustment | SE | t Value | p Value | Lower Limit 95% CI | Upper Limit 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 5.653 *** | 0.734 | 7.697 | <0.001 | 4.202 | 7.103 |

| Confounders | ||||||

| Gender | 0.060 | 0.155 | 0.391 | 0.696 | −0.245 | 0.366 |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.030 | −0.024 | 0.981 | −0.061 | 0.059 |

| Class conflict frequency | −0.104 | 0.096 | −1.079 | 0.282 | −0.295 | 0.087 |

| Conditional effects | ||||||

| Victimization | −0.298 *** | 0.068 | −4.367 | <0.001 | −0.432 | −0.163 |

| Aggressive humor | 0.058 | 0.065 | 0.887 | 0.377 | −0.071 | 0.186 |

| Affiliative humor | 0.166 * | 0.070 | 2.366 | 0.019 | 0.027 | 0.304 |

| Self-enhancing humor | 0.270 *** | 0.072 | 3.734 | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.413 |

| Self-defeating humor | −0.364 *** | 0.065 | −5.583 | <0.001 | −0.493 | −0.235 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||

| Victimization×aggressive humor | 0.145 * | 0.059 | 2.477 | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.261 |

| Victimization×affiliative humor | 0.065 | 0.053 | 1.240 | 0.217 | −0.039 | 0.170 |

| Victimization×self-enhancing humor | −0.009 | 0.038 | −0.244 | 0.808 | −0.084 | 0.066 |

| Victimization×self-defeating humor | −0.145 *** | 0.041 | −3.562 | <0.001 | −0.226 | −0.065 |

| Noninvolved | Pure Victims | Bully-Victims | ANCOVA Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | F(2, 161) | ηp2 |

| Aggressive humor style | 3.22 | 0.11 | 2.54 | 0.24 | 3.71 | 0.25 | 6.547 ** | 0.075 |

| Affiliate humor style | 5.55 | 0.12 | 4.96 | 0.26 | 5.06 | 0.27 | 3.168 * | 0.038 |

| Self-enhancing humor style | 4.47 | 0.11 | 4.08 | 0.25 | 4.53 | 0.26 | 1.241 | 0.002 |

| Self-defeating humor style | 3.08 | 0.12 | 3.41 | 0.27 | 3.84 | 0.28 | 3.548 ** | 0.042 |

| General humor use in conflicts | 3.72 | 0.08 | 3.73 | 0.18 | 3.80 | 0.19 | 0.068 | 0.0008 |

| Psychological school adjustment | 5.64 | 0.12 | 4.08 | 0.25 | 4.70 | 0.27 | 19.641 *** | 0.196 |

| Humor Class 1 “Overall High” | Humor Class 2 “Adaptive High” | Humor Class 3 “Adaptive Low” | ANCOVA Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humor-related variables | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | F(2, 162) | ηp2 |

| Aggressive humor style | 3.77 | 0.178 | 2.87 | 0.128 | 3.22 | 0.168 | 9.080 *** | 0.101 |

| Self-defeating humor style | 4.91 | 0.131 | 2.53 | 0.094 | 2.80 | 0.123 | 122.429 *** | 0.602 |

| Self-enhancing humor style | 5.01 | 0.171 | 4.51 | 0.122 | 3.69 | 0.161 | 18.027 *** | 0.182 |

| Affiliate humor style | 6.25 | 0.114 | 5.81 | 0.081 | 3.83 | 0.107 | 169.482 *** | 0.677 |

| General humor use in conflicts | 4.22 | 0.125 | 3.69 | 0.089 | 3.33 | 0.117 | 14.694 *** | 0.154 |

| Bullying and school-related variables | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | Madj | SE | F(2, 161) | ηp2 |

| Bullying victimization | 1.78 | 0.223 | 1.63 | 0.160 | 2.21 | 0.210 | 2.953 ‡ | 0.035 |

| Psychological school adjustment | 5.07 | 0.205 | 5.67 | 0.147 | 4.90 | 0.193 | 7.087 *** | 0.080 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burger, C. Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811415

Burger C. Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811415

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurger, Christoph. 2022. "Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811415

APA StyleBurger, C. (2022). Humor Styles, Bullying Victimization and Psychological School Adjustment: Mediation, Moderation and Person-Oriented Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811415