What Do We Know When We Know a Compulsive Buying Person? Looking at Now and Ahead

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Level I—Dispositional Traits and Compulsive Buying

3. Level II—Personal Concerns, Characteristic Adaptations, and Compulsive Buying

4. Level III—Life Story and Compulsive Buying

“I have a brother who is now a dentist, who was everything Mother and Dad ever wanted without question. He was bright and he was very engaging, and he is very well to do and all of that. And then there is (informant’s name) and my mother did my school work ever since I was in fifth grade. She did all of my school work even my college papers. It’s not much to be proud of”.[93] (p. 153)

“He loves to work (referring to her husband) and, in the early days when the children were very small and I was bringing them up practically single-handed, he would work Saturdays and Sundays. I would resent that so I would think, “Right, if he’s working, then I’m spending.” Now we’re in a vicious circle—I’m spending and he’s working. And I say, “Can’t you cut down the work? Can’t we go away for the weekend?” And he says, “How can I? I have to work to pay the bills.” In the early years we would have big rows about it”.[107] (p. 13)

“I ask myself now whether my problem is inherited, or whether it’s what I’ve seen, or whether I’m a dissolute person. Because my older brothers aren’t like that. The women are, though, they lied about shopping, they always said it cost less than it had; well, not when buying food; then, they said it had cost a bit more… My family, a total disaster. I don’t know to what extent this might have been an influence, a lot, I think”.[109] (p. 416)

“I would sum up my most recent years, and I do think this is a different part of my life, from the moment I left home. I was ina bad place, sick and tired of everything and looking forward to being my own person… for me it was very important to find freedom and have a job. My money gives me the possibility to decide. Well, sometimes it leads you down an undesired path, just look at me, for example. For me, money meant that I could buy many things that I had always wanted to buy. I have always liked to look good. For me, physical appearance, what others see me like, is important in life. I bought handbags, purses, I have always liked those things and a lot of clothes at the beginning of all this (she means her current buying problem), and I was very happy with myself: it was my money and I spent it on what I wanted. Well, then things changed, little by little, you get hooked and what you buy, which at first made you feel very well, then you realize you have gone too far. You feel good when you buy, but then you blame yourself and often feel bad for having spent the money”.(p. 40)

“The theme of my story? Actually, I don’t know. I think I can be up and suddenly completely down. Sometimes good things come your way. Sometimes bad things. Something like that. Sometimes life makes things hard for me and then I look and despite how bad things are, which seem really very bad, there is always a way out. Well, in my case there is not a theme, there are several. I am here because of the buying, there are also my failures. In short, I don’t know. Sometimes I feel like I was in a roller coaster or playing roulette; that would be the theme …”.(p. 49)

“It used to happen to me when I had some problem or concern. Often, when I felt bad, anxious, depressed, my way out of it was buying. While I was trying clothes on, and I was focusing my attention on whether they look good on me I could not think of anything else. Then, at that tiny instant it was like being in other world and I forgot that it had been a bad day, that I had had an argument or that something was happening. It is always a bit like that: you feel bad, and you need to buy”.(p. 66)

5. Looking Ahead: How Can We Know a Compulsive Buying Person Better?

- (1)

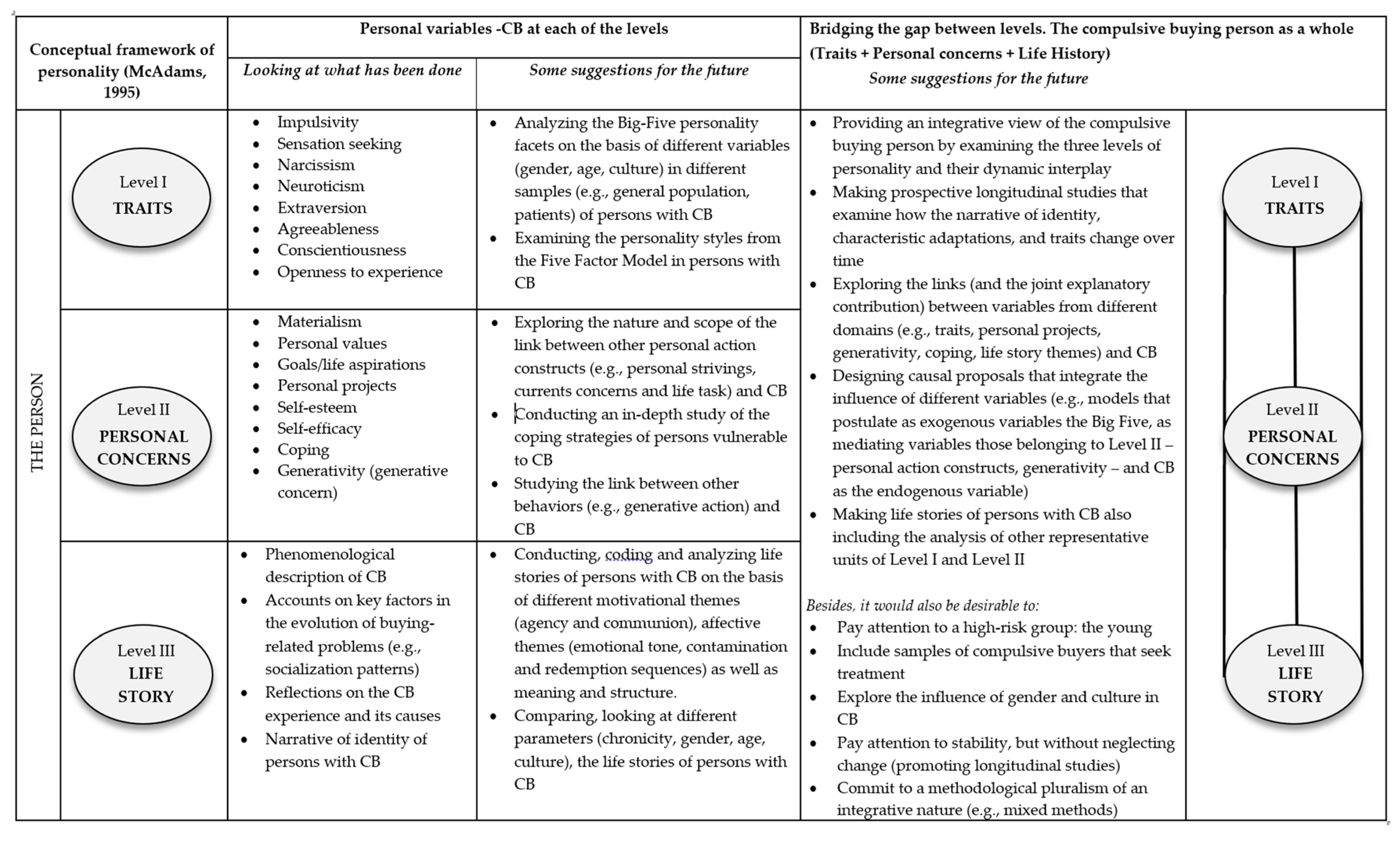

- The McAdams model: the proposal we defend. The field of compulsive buying is currently characterized, as we have already pointed out, by an abundance of studies, scattered findings, and the great variety of personal variables that are analyzed. As a consequence, ordering this complex network of influences seems to be not only necessary but also urgent. Although there are other models in the domain of personality [29], we have based our proposal on the McAdams model [32], as it is a most suggestive conceptual framework and one that is extremely useful both for identifying and classifying what it is known about the compulsive buying person and guiding future research.

- (2)

- Towards the “comprehensive understanding” of the compulsive buying person. Our proposal strives to facilitate the coexistence of different aspects (the broad and the specific, what is most endogenous and what is most situational, the statical and the dynamic elements) that need to be looked at to understand the complexity of the person and their behavior (compulsive buying, in this case). In other words, we believe that future research, while paying due attention to the study of isolated variables, should also allow for a healthy, integrative, and inclusive approach that brings together the different units that have emerged in the field to fully apprehend the compulsive buying person “as a whole”. Individual differences (level I), intentions or purposes (level II), and life story (level III) are, in our view, domains that need to be explored in depth. The purpose is therefore to complete the study of personal variables from a variety of analytical fronts without seeking complementarity and often using different grammars.

- (3)

- Building bridges, linking levels. One of the main hindrances in the field of compulsive buying is the scarcity of works that link the personal units of different levels. Despite the fact that McAdams, in the initial proposal of his model [32], held that the levels on personality should not necessarily be related to one another, later McAdams and Olson [35] claimed, in relation to personality development over the life course, that “It is expected, nonetheless, that dispositional trait, characteristic adaptations, and narrative identity should relate to each other in complex meaningful, and perhaps predictable ways; for after all, this is all about the developmental of a whole person “(p. 530). Fortunately, in the last decades, in the field of psychology of personality, things seem to be changing and notable efforts have been made to link the different levels [114,115,116,117,118]. In this line, our proposal for future research in the field of compulsive buying also suggests this desirable and much longed-for integrative approach. Linking dispositional factors with intentions and purposes, without losing sight of the present–past–future dynamic that drives the life story will allow us to approach from different avenues what makes a compulsive buyer and how they work. Ordering and sequencing the influences (exogenous, mediating…); paying attention to what is shared (individual differences) without losing sight of one’s own; exploring methodological options that have not been tested in the field of study that make it possible to combine quantitative and qualitative elements (mixed methods, for instance) would be some of the pending tasks. In sum, our intention is to convey the notion that future research should, to some extent, echo Murray and Kluchohn [119] that every person is like all other persons, like some other persons, and like no other person, as the objective is to include all things that “add up” and bring us close to a better understanding of the compulsive buying person.

- (4)

- Paying attention to a high-risk group: the young. The results of previous research confirming that young people seem to be prone to compulsive buying [8,12,120] establish the basis of the need defended by some authors [18,68,121,122] to design studies aimed at clarifying the scope and variables involved in the compulsive buying behavior of this risk group. In this regard, given the high probability that, at this age bracket, the phenomenon is at its initial stages, knowing what personal dimensions are involved in young-people compulsive buying will provide an opportunity to design early actions with some assurances of efficacy, thus stopping its progress. More specifically, the design and implementation of prevention programs focused on the critical analysis of how certain marketing campaigns contribute to “the creation of needs” and on reflecting on the socio-environmental repercussion of compulsive buying could prove useful to stop the involvement of the young in this problem. Encouraging intrinsic goals to reduce the orientation toward materialistic goals, as defended in some programs [123], seems to be part of the solution.

- (5)

- Gender and culture: influences that must not be left out. While there is empirical evidence confirming that women are highly vulnerable to compulsive buying [12,22,106], there is no shortage of studies that, using samples of young people, have failed to find any gender differences [124,125]. Therefore, the important change in the roles of women in current society, the type of items that are bought, the new online buying modes, and even the study of gender differences in pathways to compulsive buying are factors that must be considered for future research in order to delineate the true impact of the gender variable. Shedding light on to what extent culture has an impact on the personality of compulsive buying (and vice versa) and assessing the cross-cultural differences may be a new horizon for future research in this field.

- (6)

- “Identified” compulsive buyers: progressing in understanding the person. We also suggest a greater presence of samples of persons with compulsive buying problems in research, as this would undoubtedly provide an opportunity to gain a deeper and better understanding of the dynamics (evolutions, plateaus, and regressions…) that have accompanied the development of this problem. It will also become a fruitful meeting point for all three sources of knowledge of the person: “being–doing–having”. Only from this knowledge and from the analysis of the three levels in these persons (traits–concerns–life history) will it be possible to progress in the understanding of the compulsive buyer.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Müller, A.; Laskowski, N.M.; Trotzke, P.; Ali, K.; Fassnacht, D.B.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M.; Häder, M.; Kyrios, M. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder: A Delphi Expert Consensus Study. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos Pol, E. Adicción a la Compra, Materialismo y Satisfacción con la Vida. Relatos, Vidas, Compras; GEU: Granada, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-9915-092-5. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, A.; Maraz, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lejoyeux, M.; Demetrovics, Z. Compulsive Buying—Features and Characteristics of Addiction. In Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 993–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M. Compulsive Buying. Am. J. Addict. 2015, 24, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, R.J.; O’Guinn, T.C. A Clinical Screener for Compulsive Buying. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Pope, H.G.; Smith, J.M.; Strakowski, S.M. Compulsive Buying: A Report of 20 Cases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Prevalence, Sociodemographic Factors, Psychological Distress, and Coping Strategies Related to Compulsive Buying: A Cross Sectional Study in Galicia, Spain. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraz, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. The Prevalence of Compulsive Buying: A Meta-Analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, G.; Capetillo-Ponce, J.; Szczygielski, D. Compulsive Buying in Poland. An Empirical Study of People Married or in a Stable Relationship. J. Consum. Policy 2020, 43, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; Eisinger, A.; Hende, B.; Urbán, R.; Paksi, B.; Kun, B.; Kökönyei, G.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. Measuring Compulsive Buying Behaviour: Psychometric Validity of Three Different Scales and Prevalence in the General Population and in Shopping Centres. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Mitchell, J.E.; Crosby, R.D.; Gefeller, O.; Faber, R.J.; Martin, A.; Bleich, S.; Glaesmer, H.; Exner, C.; de Zwaan, M. Estimated Prevalence of Compulsive Buying in Germany and Its Association with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Depressive Symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 180, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Lam, S.C.; He, H. The Prevalence of Compulsive Buying and Hoarding Behaviours in Emerging, Early, and Middle Adulthood: Multicentre Epidemiological Analysis of Non-Clinical Chinese Samples. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 568041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; van den Brink, W.; Demetrovics, Z. Prevalence and Construct Validity of Compulsive Buying Disorder in Shopping Mall Visitors. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duroy, D.; Gorse, P.; Lejoyeux, M. Characteristics of Online Compulsive Buying in Parisian Students. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1827–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvanko, A.; Lust, K.; Odlaug, B.L.; Schreiber, L.R.N.; Derbyshire, K.; Christenson, G.; Grant, J.E. Prevalence and Characteristics of Compulsive Buying in College Students. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Shi, M. Prevalence and Co-Occurrence of Compulsive Buying, Problematic Internet and Mobile Phone Use in College Students in Yantai, China: Relevance of Self-Traits. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Unger, A.; Bi, C. Different Facets of Compulsive Buying among Chinese Students. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villardefrancos, E.; Otero-López, J.M. Compulsive Buying in University Students: Its Prevalence and Relationships with Materialism, Psychological Distress Symptoms, and Subjective Well-Being. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 65, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.W. Compulsive Shopping: A Review and Update. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H. Consumer Culture, Identity and Well-Being: The Search for the “Good Life” and the “Body Perfect”; European Monographs in Social Psychology; Psychology Press: Hove, England, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84169-608-9. [Google Scholar]

- Claes, L.; Müller, A. Resisting Temptation: Is Compulsive Buying an Expression of Personality Deficits? Curr. Addict. Rep. 2017, 4, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H. Compulsive Buying—A Growing Concern? An Examination of Gender, Age, and Endorsement of Materialistic Values as Predictors. Br. J. Psychol. 2005, 96, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchisin, J.; Johnson, K.K.P. Compulsive Buying Behavior and Its Relationship to Perceived Social Status Associated with Buying, Materialism, Self-Esteem, and Apparel-Product Involvement. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2004, 32, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.W.; Shaw, M.; McCormick, B.; Bayless, J.D.; Allen, J. Neuropsychological Performance, Impulsivity, ADHD Symptoms, and Novelty Seeking in Compulsive Buying Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rose, P. Mediators of the Association between Narcissism and Compulsive Buying: The Roles of Materialism and Impulse Control. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007, 21, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, C.E.; Watt, M.C.; Weaver, A.D.; Murphy, K.A. “I Fear, Therefore, I Shop!” Exploring Anxiety Sensitivity in Relation to Compulsive Buying. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.; Tang, C.; Gan, Y.; Kwon, J. Depressive Symptoms and Self-Efficacy as Mediators between Life Stress and Compulsive Buying: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. J. Addict. Recovery 2020, 3, 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, L.M.; Elphinstone, B. Coping Associated with Compulsive Buying Tendency. Stress Health 2021, 37, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. The Five-Factor Theory of Personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. Toward a Unified Theory of Personality: Integrating Dispositions and Processing Dynamics within the Cognitive-Affective Processing System. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 208–241. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W.; Nickel, L.B. Personality Development across the Life Course: A Neo-Socioanalytic Perspective. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P. What Do We Know When We Know a Person? J. Pers. 1995, 63, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, K.; McAdams, D.P. Personality Reconsidered: A New Agenda for Aging Research. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, P296–P304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D.P. The Psychological Self as Actor, Agent, and Author. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 272–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Olson, B.D. Personality Development: Continuity and Change Over the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Pals, J.L. A New Big Five: Fundamental Principles for an Integrative Science of Personality. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-306-42022-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, N. From Thought to Behavior: “Having” and “Doing” in the Study of Personality and Cognition. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.; Hunger, A.; Pietrowsky, R.; Gerlach, A.L. Impulsivity in Consumers with High Compulsive Buying Propensity. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2015, 7, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Rochat, L.; Rebetez, M.M.L.; Van der Linden, M. Are All Facets of Impulsivity Related to Self-Reported Compulsive Buying Behavior? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnish, R.J.; Bridges, K.R. Compulsive Buying: The Role of Irrational Beliefs, Materialism, and Narcissism. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2015, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjertsen, S.R.; Krossbakken, E.; Kvam, S.; Pallesen, S. The Relationships between Behavioral Addictions and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pallesen, S.; Bilder, R.M.; Torsheim, T.; Aboujaoude, E. The Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale: Reliability and Validity of a Brief Screening Test. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G. The Relationship between Lottery Ticket and Scratch-Card Buying Behaviour, Personality and Other Compulsive Behaviours. J. Consum. Behav. 2002, 2, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, F.F.M.; Rahim, H.A. The Effect of Personality Traits (Big-Five), Materialism and Stress on Malaysian Generation Y Compulsive Buying Behaviour. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjehan, A. The Effect of Personality on Impulsive and Compulsive Buying Behaviors. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Harnish, R.J. Consumers’ Personality and Compulsive Buying Behavior: The Role of Hedonistic Shopping Experiences and Gender in Mediating-Moderating Relationships. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, E.; Sussman, S.; Atroszko, P.A. Profiles of Potential Behavioral Addictions’ Severity and Their Associations with Gender, Personality, and Well-Being: A Person-Centered Approach. Addict. Behav. 2021, 119, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, G.; Ksendzova, M.; Howell, R.T. Sadness, Identity, and Plastic in over-Shopping: The Interplay of Materialism, Poor Credit Management, and Emotional Buying Motives in Predicting Compulsive Buying. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Five-Factor Model Personality Traits, Materialism, and Excessive Buying: A Mediational Analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E.; Castro, C. Beyond the Big Five: The Role of Extrinsic Life Aspirations in Compulsive Buying. Psicothema 2017, 29, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarska, A.; Czerwiński, S.K.; Atroszko, P.A. Measurement of Shopping Addiction and Its Relationship with Personality Traits and Well-Being among Polish Undergraduate Students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikoajczak-Degrauwe, K.; Brengman, M.; Wauters, B.; Rossi, G. Does Personality Affect Compulsive Buying? An Application of the Big Five Personality Model. In Psychology—Selected Papers; Rossi, G., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 131–144. ISBN 978-953-51-0587-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen, J.C.; Spears, N. Understanding Compulsive Buying Among College Students: A Hierarchical Approach. J. Consum. Psychol. 1999, 8, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.; Sestino, A.; Pino, G.; Guido, G.; Nataraajan, R.; Harnish, R.J. A Hierarchical Personality Approach Toward a Fuller Understanding of Onychophagia and Compulsive Buying. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 003329412110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos Pol, E. Compulsive Buying and the Five Factor Model of Personality: A Facet Analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Claes, L.; Mitchell, J.E.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Crosby, R.D.; de Zwaan, M. Personality Prototypes in Individuals with Compulsive Buying Based on the Big Five Model. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, K.; Ahmad-ur-Rehman, M.; Mehmood Cheema, A.; Ahkam, A. Impact of Personality Traits on Compulsive Buying Behavior: Mediating Role of Impulsive Buying. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2016, 09, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, L.; Sestino, A.; Guido, G. Gluttony as Predictor of Compulsive Buying Behaviour. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Akpınar, A.; Özkara, B.Y. The Impact of Neuroticism on Compulsive Buying Behavior: The Mediating Role of the Past-Negative Time Perspective and the Moderating Role of the Consumer’s Need for Uniqueness. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, A.; Costa, P.T. Smoking and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Addiction 2004, 99, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, C.C.; Becker, S.J.; Curry, J.F. Personality Factors and Styles among College Students Who Binge Eat and Drink. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009, 23, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. Materialism Pathways: The Processes That Create and Perpetuate Materialism. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Dawson, S. A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Hurst, M.; Kasser, T. The Relationship between Materialism and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 879–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnish, R.J.; Bridges, K.R.; Gump, J.T.; Carson, A.E. The Maladaptive Pursuit of Consumption: The Impact of Materialism, Pain of Paying, Social Anxiety, Social Support, and Loneliness on Compulsive Buying. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Mitchell, J.E.; Peterson, L.A.; Faber, R.J.; Steffen, K.J.; Crosby, R.D.; Claes, L. Depression, Materialism, and Excessive Internet Use in Relation to Compulsive Buying. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Pullig, C.; David, M. Family Conflict and Adolescent Compulsive Buying Behavior. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSarbo, W.; Edwards, E. Typologies of Compulsive Buying Behavior: A Constrained Clusterwise Regression Approach. J. Consum. Psychol. 1996, 5, 231–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Claes, L.; Georgiadou, E.; Möllenkamp, M.; Voth, E.M.; Faber, R.J.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M. Is Compulsive Buying Related to Materialism, Depression or Temperament? Findings from a Sample of Treatment-Seeking Patients with CB. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 216, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Materialismo y adicción a la compra. Examinando el papel mediador de la autestima. Bol. Psicol. 2011, 103, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Pol, E.V.; Bolaño, C.C.; Mariño, M.J.S. Materialism, Life-Satisfaction and Addictive Buying: Examining the Causal Relationships. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, S.S.; Eroğlu, F.; Hacioglu, G. Compulsive Buying Tendencies through Materialistic and Hedonic Values among College Students in Turkey. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, C.; Roberts, J.A. Subjective Well-Being among Adolescent Consumers: The Effects of Materialism, Compulsive Buying, and Time Affluence. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2012, 7, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Materialism and Addictive Buying in Women: The Mediating Role of Anxiety and Depression. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 113, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.W.; Tang, C.S.; Wu, A.; Yan, E. Gender Differences in Pathways to Compulsive Buying in Chinese College Students in Hong Kong and Macau. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarka, P.; Harnish, R.J.; Babaev, J. From Materialism to Hedonistic Shopping Values and Compulsive Buying: A Mediation Model Examining Gender Differences. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tarka, P.; Harnish, R.J. Toward the Extension of Antecedents of Compulsive Buying: The Influence of Personal Values Theory. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 2018–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarska, A.; Czerwiński, S.K.; Atroszko, P.A. Shopping Addiction Is Driven by Personal Focus Rather than Social Focus Values but to the Exclusion of Achievement and Self-Direction. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G.; Capetillo-Ponce, J.; Szczygielski, D. Links between Types of Value Orientations and Consumer Behaviours. An Empirical Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasser, T. Materialistic Values and Goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Perspectives in Social Psychology; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-306-42022-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4625-2876-9. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.A.; Pirog, S.F. Personal Goals and Their Role in Consumer Behavior: The Case of Compulsive Buying. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2004, 12, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Compulsive Buying and Life Aspirations: An Analysis of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goals. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Santiago, M.J.; Castro, M.C. Life Aspirations, Generativity and Compulsive Buying in University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. The Psychology of Life Stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.R. The Integrative Challenge in Personality Science: Personal Projects as Units of Analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 56, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Santiago, M.J.; Castro, M.C. Personal Projects’ Appraisals and Compulsive Buying among University Students: Evidence from Galicia, Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, R.J. Money Changes Everything: Compulsive Buying From a Biopsychosocial Perspective. Am. Behav. Sci. 1992, 35, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherhorn, G. The Addictive Trait in Buying Behaviour. J. Consum. Policy 1990, 13, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Guinn, T.C.; Faber, R.J. Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, N.M.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Monroe, K.B. An Expanded Conceptualization and a New Measure of Compulsive Buying. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, J.A.; Manolis, C.; Pullig, C. Contingent Self-Esteem, Self-Presentational Concerns, and Compulsive Buying. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolcati, R. The Role of Self-Esteem and Fear of Negative Evaluation in Compulsive Buying. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Chu, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, Z. Perceived Stress and Online Compulsive Buying among Women: A Moderated Mediation Model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 103, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O.; Khoi, N.H.; Tuu, H.H. The “Well-Being” and “Ill-Being” of Online Impulsive and Compulsive Buying on Life Satisfaction: The Role of Self-Esteem and Harmony in Life. J. Macromark. 2022, 42, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Adair, Z. Psychological Aspects of Shopping Addiction: Initial Test of a Stress and Coping Model. Int. J. Psychol. Brain Sci. 2021, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, E.; Sitko-Dominik, M.; Wysocka, E.; Olszanecka-Marmola, A. Exploring the Roles of Daily Spiritual Experiences, Self-Efficacy, and Gender in Shopping Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model. Religions 2021, 12, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Santiago, M.J.; Castro, M.C. Big Five Personality Traits, Coping Strategies and Compulsive Buying in Spanish University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Köse, G.G. Mediating Effect of Intolerance of Uncertainty in the Relationship between Coping Styles with Stress during Pandemic (COVID-19) Process and Compulsive Buying Behavior. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; de St. Aubin, E. A Theory of Generativity and Its Assessment through Self-Report, Behavioral Acts, and Narrative Themes in Autobiography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Hart, H.M.; Maruna, S. The Anatomy of Generativity. In Generativity and Adult Development: How and Why We Care for the Next Generation; McAdams, D.P., de St. Aubin, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 7–43. [Google Scholar]

- Urien, B.; Kilbourne, W. Generativity and Self-Enhancement Values in Eco-Friendly Behavioral Intentions and Environmentally Responsible Consumption Behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherhorn, G.; Reisch, L.A.; Raab, G. Addictive Buying in West Germany: An Empirical Study. J. Consum. Policy 1990, 13, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, S. The Lived Experiences of Women as Addictive Consumers. J. Res. Consum. 2002, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.; Eccles, S.; Gournay, K. Revenge, Existential Choice, and Addictive Consumption. Psychol. Mark. 1996, 13, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I. Addictive Buying: Causes, Processes, and Symbolic Meanings. Thematic Analysis of a Buying Addict’s Diary. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 408–422. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Luengo, M.A.; Romero, E.; Gómez, J.A.; Castro, C. Psicología de la Personalidad. Manual de Prácticas; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-84-344-0956-9. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative Identity: What Is It? What Does It Do? How Do You Measure It? Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 2018, 37, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.M.; Dunlop, W.L.; Fivush, R.; Lilgendahl, J.P.; Lodi-Smith, J.; McAdams, D.P.; McLean, K.C.; Pasupathi, M.; Syed, M. Research Methods for Studying Narrative Identity: A Primer. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.C.; Syed, M.; Pasupathi, M.; Adler, J.M.; Dunlop, W.L.; Drustrup, D.; Fivush, R.; Graci, M.E.; Lilgendahl, J.P.; Lodi-Smith, J.; et al. The Empirical Structure of Narrative Identity: The Initial Big Three. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 920–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, I.; de Lima, M.P.; Matos, M.; Figueiredo, C. The Interplay Among Levels of Personality: The Mediator Effect of Personal Projects Between the Big Five and Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, J.L.; Weidmann, R.; Grob, A. The Actor, Agent, and Author across the Life Span: Interrelations between Personality Traits, Life Goals, and Life Narratives in an Age-Heterogeneous Sample. Eur. J. Personal. 2021, 35, 168–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Klevan, M.; McAdams, D.P. Personality Traits, Ego Development, and the Redemptive Self. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D.P.; Anyidoho, N.A.; Brown, C.; Huang, Y.T.; Kaplan, B.; Machado, M.A. Traits and Stories: Links Between Dispositional and Narrative Features of Personality. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, I.; McAdams, D.P.; Little, B.R. Personal Projects, Life Stories, and Happiness: On Being True to Traits. J. Res. Personal. 2006, 40, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H.A.; Kluckhohn, C. Outline of a Conception of Personality. In Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture; Kluckhohn, C., Murray, H.A., Schneider, D., Eds.; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1953; pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios, M.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Ali, K.; Maclean, B.; Moulding, R. Predicting the Severity of Excessive Buying Using the Excessive Buying Rating Scale and Compulsive Buying Scale. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2020, 25, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Wei, J.; Sheikh, Z.; Hameed, Z.; Azam, R.I. Determinants of Compulsive Buying Behavior among Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Materialism. J. Adolesc. 2017, 61, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Brito, M.; Hernández-García, M.; Rodríguez-Donate, M.; Romero-Rodríguez, M.; Darias-Padrón, A. Compulsive buying behavior of Smartphones by university students. CNS Spectr. 2022, 27, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, N.; Kasser, T.; Bardi, A.; Gatersleben, B.; Druckman, A. Goals for Good: Testing an Intervention to Reduce Materialism in Three European Countries. Eur. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Workman, J.E. Consumer tendency to regret, compulsive buying, gender, and fashion time-of-adoption groups. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2018, 11, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Tanner Jr, J.F. Compulsive buying and risky behavior among adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 86, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspal, R.; Lopes, B.; Lopes, P. Predicting social distancing and compulsive buying behaviours in response to COVID-19 in a United Kingdom sample. Cogent Psychol. 2020, 7, 1800924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; Yi, S. Compulsive buying gradually increased during the first six months of the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nuclear Episode | Fragments of the Life Story |

|---|---|

| High point: “Having found a partner who had his feet on the ground” | “The day I broke up with my partner and then when I found another person with his feet on the ground that helps me control myself as much as he can, because of the problem linked to buying… those days in which it seemed I had woken up from a bad dream … being able to say Stop! …When I decided… when I took a weight off my mind, I felt, I don’t know., a great relief” |

| Low point: “My parents’ separation” | “I went out to dinner with my parents and at the table, out of the blue, he tells us he is going to ask for a divorce and that he had another partner. I was astonished I thought so many things ... What was my mother going to do now? … That week was terrifying because it was all threats, thumping of the walls and slamming doors shut. Then I didn’t want to go home… there was an overwhelming sensation of I don’t know … powerlessness … That was unbearable” |

| Turning point: “The day I decide to leave my family home” | “Leaving behind all that shouting, that bad blood, that being always on edge...It was being in hell and then getting out and setting myself free. I have always believed that resentment is a heavy load, and I didn’t want to continue like that. Resentment always takes the place of bitterness and I prefer to be more cheerful, think of other things… I told myself that from that moment on the person I would be with would not impose themselves on me or repress me. Never again. I needed to be myself... To me, being independent came first, the most important thing I had done in my life… I would not let anyone do what they had done to me. Never again. Then, that meant for me saying: Now I am in charge!... I left, I started again… I changed radically. I rented a flat, and well then came the bad stuff with the buying …” |

| First recollection: “One morning of the Three Kings Day” | “I remember being hidden behind the sofa with my bother for quite some time, whispering and we were dying for opening the presents. I particularly remember that desire for the day to come so that I could open the presents…” |

| Scene from childhood: “Arguments with my mother about clothes and hairstyles” | “I especially remember the rows with my mother because of the hairstyles and the clothes she insisted on me wearing … I remember when I went to my uncle’s wedding. No one knows how much I cried and acted up not to wear those clothes. I cried till the day of the wedding. To me it looked horrendous. Actually, I thought about getting rid of them, I had the scissors in my hand, but then I did not dare …” |

| Scene from adolescence: “Going to the high school” | “I often remember that for a time I hung out with a group of girls from another high school who I think instilled in me the excessive concern about dressing well… although that was there before. They were people who went like “I look super good today... I am stunning today, I look super great”, they were very superficial.” |

| Scene from adulthood: “When I went to live on my own” | “I wanted to show the world that I could live alone. I told myself. I am independent. I have a job. I can live in my own flat. It was a studio apartment with a kitchen, very tiny. But I tried to be always with people. But there were also bad times. Sometimes I thought “now I am going to go to sleep and tomorrow I’ll see things differently. But that did not happen. Soon everything got complicated, and numbers didn’t add up. Then, there came the bank statements and loneliness … I no longer had any health either.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otero-López, J.M. What Do We Know When We Know a Compulsive Buying Person? Looking at Now and Ahead. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811232

Otero-López JM. What Do We Know When We Know a Compulsive Buying Person? Looking at Now and Ahead. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811232

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtero-López, José Manuel. 2022. "What Do We Know When We Know a Compulsive Buying Person? Looking at Now and Ahead" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811232

APA StyleOtero-López, J. M. (2022). What Do We Know When We Know a Compulsive Buying Person? Looking at Now and Ahead. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811232