An Individually Tailored Program to Increase Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors among the Elderly

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Participants

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Research Procedure

2.2.1. About the Program

2.2.2. Program Components

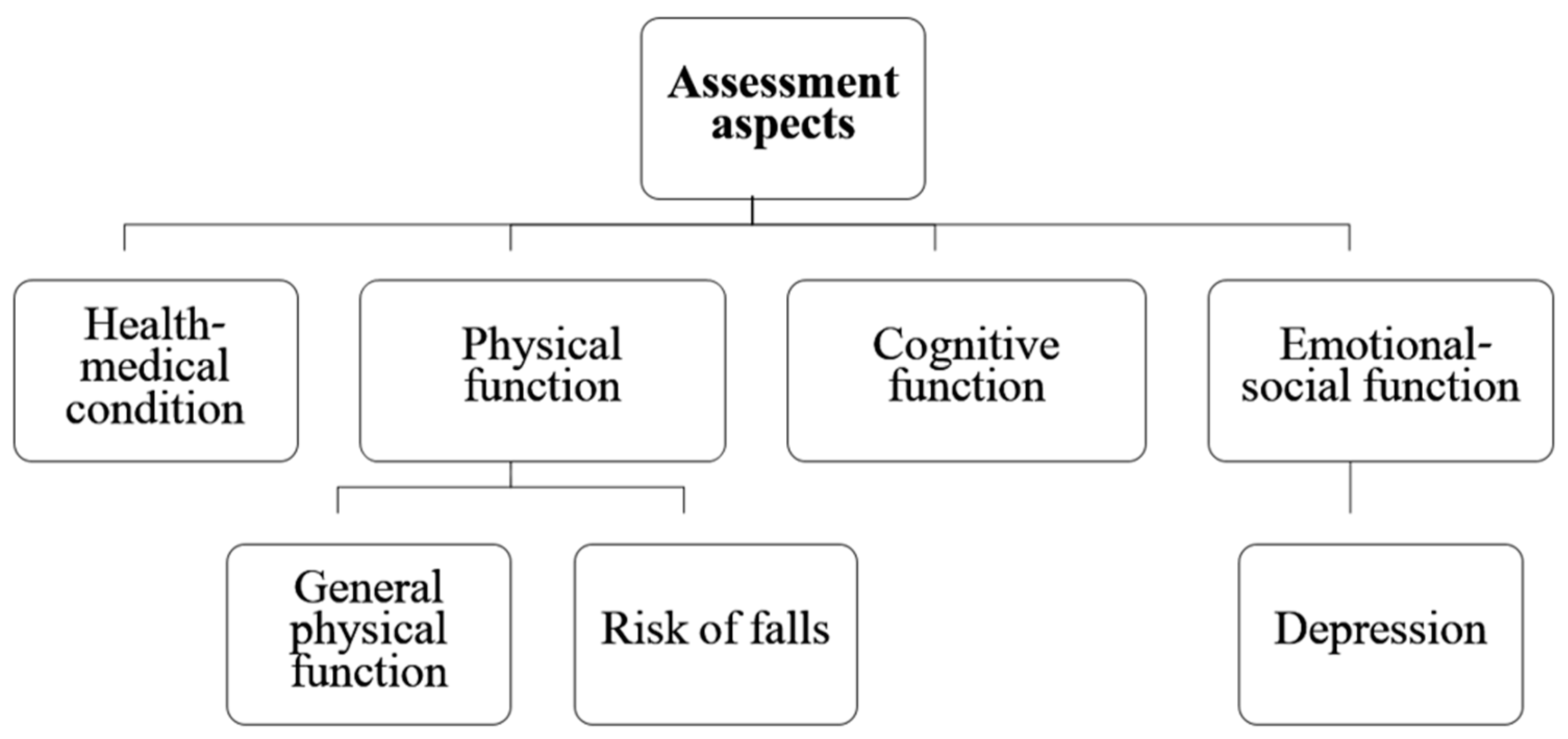

- Part A—Health–medical status: This section includes nine questions related to the participants’ health condition and morbidity. The consisted of questions that may indicate a state of frailty (e.g., unintentional weight loss of more than 5 kg [19] and common morbidity conditions in old age (e.g., heart disease and stroke). Based on the total score, participants were categorized as having low, medium, or high health–medical condition status.

- Part B—Physical function: This part of the questionnaire includes 11 questions. Some of the questions deal with the person’s general level of functioning (for example, walking ability, ability to perform daily actions, instrumental actions of daily actions), and history of falls (for example, number of falls in the last year). Based on the total score, participants were categorized as having low, medium, or high physical function status and/or at risk for falling.

- Part C—Cognitive function: Cognitive function was assessed using the Alzheimer’s disease-8 (AD8) questionnaire [20]. In community-residing older adults, AD8 shows excellent internal reliability (Cronbach alpha = 0.84), excellent internal consistency, and strong interrater reliability and stability [21]. A score of 2 or more is commonly used as the cut-off score to indicate dementia [22].

- Part D—Emotional–social function: Emotional–social function was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). This questionnaire includes two questions that deal with the frequency of onset of symptoms of depression and discomfort on a scale ranging from zero (not at all) to three (almost every day). The sensitivity and specificity of the assessment tool in identifying clinical depression is 74 and 91% with a score of three or higher [23]. Accordingly, from this part of the questionnaire, the person’s emotional state was classified into one of two levels—there may be emotional problems or no emotional problems.

2.2.3. The Training Process of the Program’s Staff

2.2.4. Description of the Meetings between the Students and the Elderly

- First conversation—Acquaintance with the program (e.g., background of the program and its goals).

- Second conversation—Presentation of the functional assessment questionnaire and determination of how to complete the questionnaire (independently or with the help of the student). Those who were capable to complete the questionnaire independently were instructed to do so until the following conversation.

- Third conversation—For those who completed the assessment independently, the student and the elderly person discussed the participant’s experience with the questionnaire. For those who needed help with the questionnaire, the students filled it in with the elderly person.

- Fourth conversation—A joint review of the assessment’s recommendations, selection of recommendations for implementation, and prioritizing them by the elderly person. Finally, construction of a plan for the implementation of the recommendations.

- Fifth conversation—Identifying factors that promote and delay the implementation of the recommendations. In this phase, the students also encouraged and motivated the participant to comply with the recommendations given to and selected by them.

- Sixth conversation—Monitoring compliance with the implementation of the selected recommendations.

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.3.1. Demographic and Functional Characteristics

2.3.2. Participants’ Perception on the Health-Related Recommendations They Received

2.3.3. Healthy Lifestyle Recommendations and Implementation

2.3.4. Facilitators and Barriers to Healthy Lifestyle Recommendations Implementation

2.4. Data Analyses

2.4.1. Demographic and Functional Characteristics of Study Participants and Attrition Group

2.4.2. Participants’ Perception on and Compliance with the Healthy Lifestyle-Related Services Recommended

2.4.3. Facilitators, Barriers, and Predictors of Compliance with Health-Related Services

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Functional Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Involvement in Health Promotion Activities

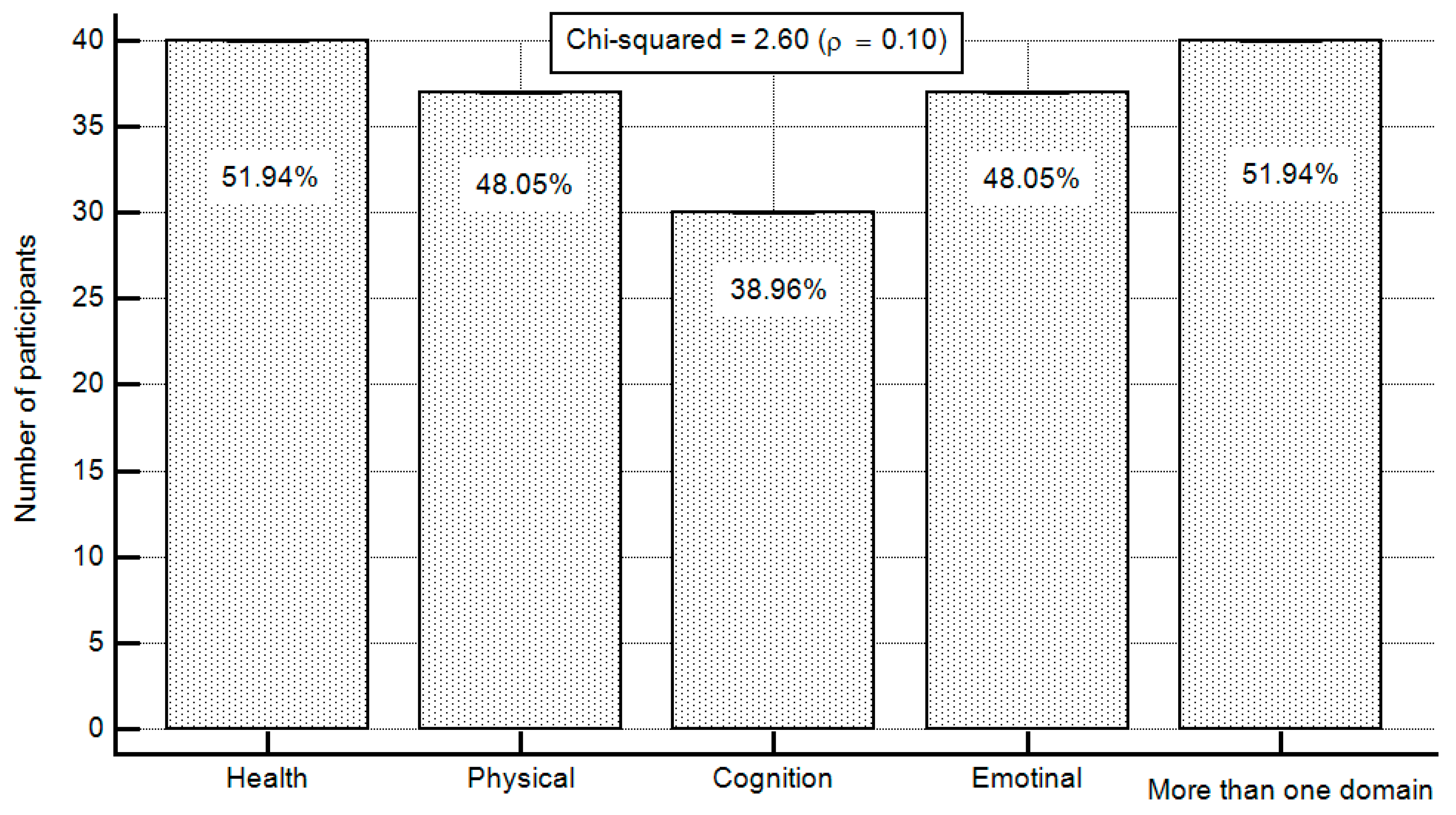

3.3. Types of Services Participants Are Interested in Receiving Information About

3.4. Participants’ Perception on the Health-Related Recommendations They Received

3.5. Frequency of Compliance with the Recommended Health-Related Recommendations

3.6. Facilitators and Barriers to Compliance with the Health-Related Recommendations Received

3.7. Factors Associated with and Predicting Compliance with the Health-Related Recommendations Received

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Why Population Aging Matters: A Global Perspective. Publication Number 07.6134. United States of America. 2007. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-06/WPAM.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Health and Aging; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Physical Activity and Healthy Ageing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 38, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Associations of Smoking and Alcohol Consumption with Healthy Ageing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kralj, C.; Daskalopoulou, C.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; García-Esquinas, E.; Cosco, T.; Prince, M.; Prina, A. Healthy Ageing: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. King’s Glob. Health Inst. Rep. 2018, 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia; Ministry of Health. Healthy Aging through Healthy Living, towards A Comprehensive Policy and Planning Framework for Seniors in B.C.: A Discussion Paper; Ministry of Health: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7726-5461-8.

- Health Canada. Part1: Aging and Health Practices. In Division of Aging and Seniors Dare to Age Well: Workshop on Healthy Aging; Works and Government Services: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lemme, B.H. Development in Adulthood, 2nd ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Keadle, S.K.; McKinnon, R.; Graubard, B.I.; Troiano, R.P. Prevalence and Trends in Physical Activity among Older Adults in the United States: A Comparison across Three National Surveys. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notthoff, N.; Reisch, P.; Gerstorf, D. Individual Characteristics and Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontology 2017, 63, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, T.; Mengistu, B.; Atnafu, A.; Derso, T. Malnutrition and Its Determinants among Older Adults People in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, C.W.; Johnson, M.A. Chapter 56: Nutrition in Older Adults. In Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease; Wolters Kluwer Business: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 744–756. [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz, Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) Review of the Literature—What Does It Tell Us? J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 466–485; discussion 485–487. [Google Scholar]

- Zubala, A.; MacGillivray, S.; Frost, H.; Kroll, T.; Skelton, D.A.; Gavine, A.; Gray, N.M.; Toma, M.; Morris, J. Promotion of Physical Activity Interventions for Community Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Reviews. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-674-22457-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.-Y. Factors Associated with Successful Aging among Community-Dwelling Older Adults Based on Ecological System Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zastrow, C.; Kirst-Ashman, K.K. Understanding Human Behavior and The Social Environment, 8th ed.; Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-495-60374-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, J.E.; Roe, C.M.; Powlishta, K.K.; Coats, M.A.; Muich, S.J.; Grant, E.; Miller, J.P.; Storandt, M.; Morris, J.C. The AD8: A Brief Informant Interview to Detect Dementia. Neurology 2005, 65, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvin, J.E.; Roe, C.M.; Coats, M.A.; Morris, J.C. Patient’s Rating of Cognitive Ability: Using the AD-8, A Brief Informant Interview, as a Self-Rating Tool to Detect Dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2007, 64, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendry, K.; Green, C.; McShane, R.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; Stott, D.J.; Anwer, S.; Sutton, A.J.; Burton, J.K.; Quinn, T.J. AD-8 for Detection of Dementia across a Variety of Healthcare Settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD011121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroll, B.; Goodyear-Smith, F.; Crengle, S.; Gunn, J.; Kerse, N.; Fishman, T.; Falloon, K.; Hatcher, S. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to Screen for Major Depression in the Primary Care Population. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010, 8, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, A.; Kosecoff, J.; Chassin, M.; Brook, R.H. Consensus Methods: Characteristics and Guidelines for Use. Am. J. Public Health 1984, 74, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications; Duxbury/Thompson Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, M.; Gilroy, V. Specialist Community Public Health Nurses: Readiness for Practice. Community Pract. 2014, 87, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Delamaire, M.; Lafortune, G. Nurses in Advanced Roles: A Description and Evaluation of Experiences in 12 Developed Countries. OECD Health Work. Pap. 2010, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Drevenhorn, E.; Carlsson, G. Nurses’ Experiences of Promoting Healthy Aging in the Municipality: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezen, M.G.H.; Mathijssen, J.J.P. Reframing Professional Boundaries in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Facilitators and Barriers to Task Reallocation from the Domain of Medicine to the Nursing Domain. Health Policy 2014, 117, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ng, O.-L.; Ha, A.S.C. A Qualitative Exploration of Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity Participation among Chinese Retired Adults in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A Taxonomy of Behavior Change Techniques Used in Interventions. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Czaja, S.J.; Sharit, J.; Ownby, R.; Roth, D.L.; Nair, S. Examining Age Differences in Performance of a Complex Information Search and Retrieval Task. Psychol. Aging 2001, 16, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, L. Enhancing the Attitudes and Self-Efficacy of Older Adults Toward Computers and the Internet: Results of a Pilot Study. Educ. Gerontol. 2008, 34, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinowska, S.; Groot, W.; Baji, P.; Pavlova, M. Health promotion targeting older people. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.; Janssens, A.; Dunn-Morua, S.; Eke, H.; Asherson, P.; Lloyd, T.; Ford, T. Seven steps to mapping health service provision: Lessons learned from mapping services for adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the UK. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Mean (SD) (Range) or n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | Age, years: mean (SD) | 72.98 (6.49) (60–87) | |

| Sex: n (%) | Females | 53 (68.8) | |

| Males | 24 (31.2) | ||

| Family status: n (%) | Married | 32 (41.6) | |

| Single | 6 (7.8) | ||

| Divorced | 8 (10.4) | ||

| Widow | 31 (40.3) | ||

| Education: n (%) | High school | 28 (36.4) | |

| Tertiary education | 12 (15.6) | ||

| Academic | 37 (48.1) | ||

| Income: n (%) | Below average | 39 (50.6) | |

| Average | 28 (36.4) | ||

| Above average | 10 (13.0) | ||

| Functional characteristics | General health: n (%) | Low | 12 (15.6) |

| Moderate | 32 (41.6) | ||

| High | 33 (42.9) | ||

| Physical: n (%) | Low | 14 (18.2) | |

| Moderate | 25 (32.5) | ||

| High | 38 (49.4) | ||

| Falls risk: n (%) | At risk | 52 (67.5) | |

| Not at risk | 25 (32.5) | ||

| Cognitive: n (%) | Difficulties | 16 (20.8) | |

| No difficulties | 61 (79.2) | ||

| Emotional: n (%) | Difficulties | 9 (11.7) | |

| No difficulties | 68 (88.3) | ||

| Questions | Not at All/Somewhat: n (%) | A Lot: n (%) | Chi-Squared (p Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning from the recommendations | Did you learn new things about yourself from the results? | 56 (72.72) | 21 (27.27) | 30.98 (<0.001) |

| To what extent were the recommendations you received new to you? | 53 (68.83) | 24 (31.16) | 20.94 (<0.001) | |

| Recommendations and motivation | To what extent did the recommendations you receive increase your motivation to engage in healthy behaviors? | 22 (28.57) | 55 (71.42) | 28.29 (<0.001) |

| To what extent did the recommendations you receive decrease your motivation to engage in healthy behaviors? | 68 (88.31) | 9 (11.68) | 90.72 (<0.001) | |

| Frequency of Compliance with the Recommendations | Never: n (%) | 1–2/Week: n (%) | 3–6/Week: n (%) | Every Day: n (%) | Chi-Squared (p Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation number | 1 | 11 (14.28) c | 17 (22.07) c | 29 (37.66) a,b | 20 (25.97) | 10.87 (0.001) |

| 2 | 13 (16.88) c | 13 (16.88) c | 30 (38.96) a,b | 21 (27.27) | 9.26 (0.002) | |

| 3 | 14 (18.18) c | 13 (16.88) c | 30 (38.95) a,b | 20 (25.97) | 9.25 (0.002) | |

| Factor | Item Description | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Personal | Healthy behavior motivation | 46 (59.74) |

| Sense of self-efficacy | 40 (51.94) | ||

| Defining a working plan | 22 (28.57) | ||

| Being healthy | 34 (44.15) | ||

| Environmental | Help and encouragement of family members and friends | 35 (45.45) | |

| Respecting attitude from health care providers and office holders | 12 (15.58) | ||

| Accessible information about services | 2 (2.59) | ||

| Barriers | Personal | Lack of motivation | 4 (5.19) |

| Lack sense of self-efficacy, independence, and hope | 8 (10.38) | ||

| Unfocused working plan | 12 (15.58) | ||

| Being unhealthy | 12 (15.58) | ||

| Environmental | Lack of help and encouragement of family members and friends | 2 (2.59) | |

| Unrespecting attitude from health care providers and office holders | 8 (10.38) | ||

| Inaccessible information about services | 25 (32.46) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barak, S.; Rabinovitz, T.; Akiva-Maliniak, A.B.; Schenker, R.; Meiry, L.; Tesler, R. An Individually Tailored Program to Increase Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors among the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711085

Barak S, Rabinovitz T, Akiva-Maliniak AB, Schenker R, Meiry L, Tesler R. An Individually Tailored Program to Increase Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors among the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711085

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarak, Sharon, Tzlil Rabinovitz, Achinoam Ben Akiva-Maliniak, Rony Schenker, Lian Meiry, and Riki Tesler. 2022. "An Individually Tailored Program to Increase Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors among the Elderly" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711085

APA StyleBarak, S., Rabinovitz, T., Akiva-Maliniak, A. B., Schenker, R., Meiry, L., & Tesler, R. (2022). An Individually Tailored Program to Increase Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors among the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711085