Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

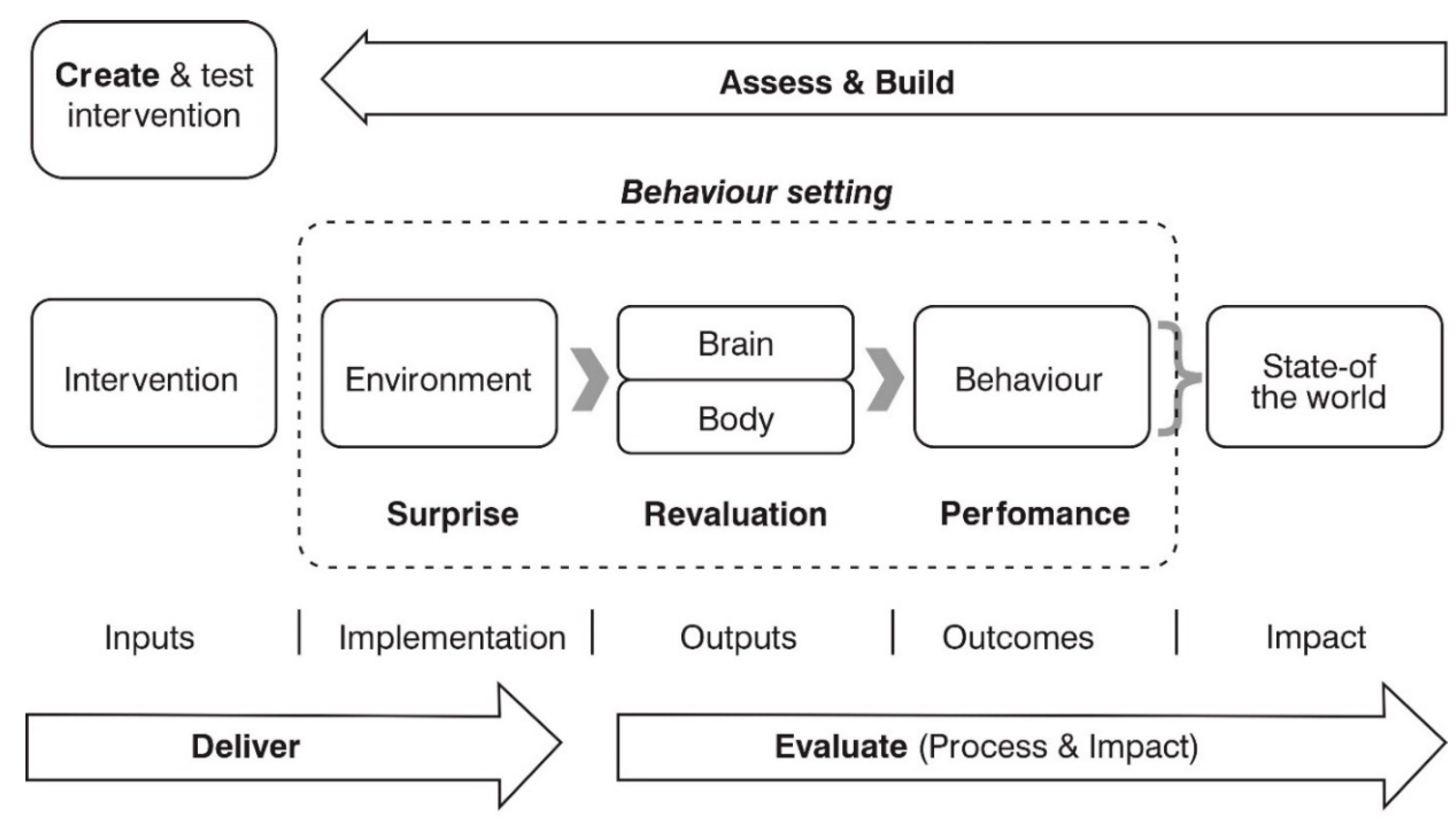

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of FGD Participants

3.2. Drivers of Waste Segregation and Recycling

3.2.1. Environment-Related Drivers

Physical Environment

“The nature and size of places/homes where people live, they don’t have enough space to do the segregation of their waste since everyone is just next to the neighbor’s doors because of the nature of our housing.”P31: Key informant Kasubi

“A person would not have thrown solid waste in the channel when the skip is near. A person would not throw solid waste at another person’s veranda when the skip is near but unfortunately the available skips are usually far away from the households. One considers the journey they have to take and sometimes does not have the 500 shillings (0.137 USD) to pay a child for delivering the waste to the refuse skip, and decides to dump it there. So, it affects us if refuse skips or segregation waste collecting centers are far, because of the high accumulation rate of solid waste in communities that are spread apart.”P28: Key informant Wandegeya

Social Environment

“We have tried to collaborate as neighbors to do certain things together like encouraging each person to have a collection sack next to their doors, we also separate charcoal dust and a few other wastes and reuse them for making briquettes. We also try to collectively pay for the waste as neighbors in order to reduce on the cost irrespective of the tempers and our differences.”P6: Participant FGD Kasubi-Residential

“As the local authorities, we keep referring other families to those who make briquettes and have earned a living from them as a way of encouraging them to embrace segregation, reuse and recycling as a way of generating income.”P22: Local leader-Makerere 1

3.2.2. Brains Related Drivers

Executive Brain

“...we hear that many things can be made of solid waste but in hearing that, we need to get trainings like on Bukedde TV. I saw that the maize remains are used in making flowers. They cooked together with the dye for making sisal and make different designs. We would be able to get things from wastes when we are taught, but how will I know without getting trainings on reusing or recycling solid wastes like bottles.”P34: FGD 3 Makerere 1 Residents

“We don’t segregate this waste; we just mix everything together except for the peelings from food since it is collected by farmers for animal feeds.”P6: Participant FGD Kasubi

Motivated Brain

“Because they are sure if they collect banana and cassava peelings in one bag, people with animals will come looking for feeds, so they are able to sell to them and make money.”P8: Local leader-Kamwokya

“What I see mostly motivating people are those that buy the plastic bottles from the people and recycle them. People fight for the plastic bottles and this encourages them to sort them out of other waste streams. The people having animals also encourage residents to sort the food peelings from the other garbage since they pay about Uganda shillings 500 (approximately 0.137 USD) per 200 liter container to get them from residents.”P35: Participant FGD Kamwokya

“It comes to money. Let us say there is a weighing scale that buys plastics. People would not play around with plastics because someone has got what to do. Like how we hear that electricity comes from wastes, there comes, and area where they collect wastes from and buy it. I will relate it on money. For example, there is market for scrap metals and you cannot find them everywhere. So, when they put in money that will end.”P34: FGD 3 Makerere 1 Resident

“In addition, farmers dump their sacks in the families to get the food remains. Some of them have animals like pigs to feed while the others have plantations that need organic manure or biodegradable waste materials. This helps many people sort the rubbish and make sure they fill the sacks. Each sack (with a volume of about 200 liters) is Uganda shillings 500 (approximately 0.137 USD) so they fill it up in order to get the money.”P16: Key informant, Bukoto

“...they should help us and bring those trainings on solid waste segregation. We should follow them and keep humanity by keeping the wastes so that it doesn’t make our children and us sick. We keep clean and protect ourselves, when we separate food remains bottles, broken plates and other items.”P3: Participant FGD Katanga

“There is a Chinese (in company Y) who said that all the plastic bottles and bags should be taken to him in Nakawa. A kilogram is at 100 shillings (0.027 USD). The road cleaners and sweepers worked hard to gather all these plastics and take for the Chinese but a woman would carry three bags of plastics and gets only 5000 shillings (1.368 USD). They got demotivated and stopped. Those that pick the plastics I am not sure how much they get from them. But the people making briquettes and straw mats get some good money from the garbage.”P24: Key informant Bukoto 1

“Why should I segregate yet when (company X) comes, it is going to come back and mix and also when the collectors don’t make the arrangements of where to take the segregated waste? There are some challenges there because you can only comfortably segregate when you know I am picking plastics and taking them to a known plastic recycling company. There will be that motivation.”P35 Key informant, private waste company

3.2.3. Body Related Drivers

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

“Yeah, this (waste segregation) is mostly done in organized institutions like schools, hospitals, housing estates, barracks and other settlement patterns like Nakasero and Kololo. People do because they are educated, have access to infrastructure within their settings, and they can afford to pay for the segregation bins and others waste management services.”P10: Key informant waste collection company

Human Senses

“The problem we find from wastes is the smell. For example, a person may slaughter their hen, collects the blood, feathers and intestines in a polythene bag, and dumps the bag with other waste streams in a residential setting. Segregation of solid waste at source is a problem and people mix pampers, pads, plastic bottles, food remains and other waste streams. Removing useful products from such mixtures is difficult because of the smells that arise from the storage containers or sacks.”P34: Participant FGD 3 Makerere 1 Residents

Capabilities

“We have not really considered segregating waste except for some few people who have attended some training workshops, and they have been making animal feeds from some waste streams but the rest is discarded in sacks as a mixture irrespective of the differences in the kinds of waste...”P6: Participant FGD Kasubi

“...if we have people that can teach us waste recycling innovations, e.g., if they tell us you can recycle plastics in a certain explained way, we can group up as women in the community and create our own businesses to improve the management and recycling of the waste that surrounds us.”P33: Key Informant Kasubi zone 2

“Some people are ignorant about it and others that know about recycling are weak or lazy to do it. They would desire to recycle the rubbish even under instructions but their bodies are weak. The briquettes you see require time to make them from the banana peelings.”P12: Key informant Bukoto

3.2.4. Behavior Setting Drivers

Stage

“Areas with low crime rates and fewer cases of theft are most likely to have better waste segregation and recycling rates. In areas with high crime rates, urban dwellers sometimes steal the storage/segregation sacks and pour rubbish in front of the owner’s home. This is because the sacks have monetary value. The sack alone costs 500 Shillings (approximately 0.137 USD) which is quite lucrative for the people in the slum community.”P19: Key Informant, government parastatal

“...We have bins that we put on the road side for the pedestrians having yoghurt or soda to dump the rubbish there. But a person leaves home at 5 a.m. before KCCA starts working and they dump their garbage in the small bin. Sometimes they dump the large garbage next to the bin because they are sure that KCCA will come and collect the garbage from the bin. Those are some of the challenges KCCA faces. But the markets have these bins.”P24: Key informant Bukoto

Roles

“There are people who pay solid waste collection fees, ranging between 3000–5000 Uganda shillings (0.821–1.367 USD) and waste collection companies spend more than 1 month without showing up at all. Companies that buy segregated waste items can also take long without showing up in communities where some waste segregation happens. What follows are the kids who keep lying that the garbage collectors have come and once you give them some money like 1000 Uganda shillings (0.274 USD) for waste disposal, they just turn the next corner and abandon the solid waste at the neighbor’s place and disappear. Others detest paying for garbage on top of the rent they remit thus keeping dumping the rubbish in other places in smaller portions of polythene”P32: FGD participant Kasubi

“It is a dirty job; the perception of communities on wastes is also an issue that whoever works on waste, people think they are of low level, like they are failures and no one wants to be associated with that. No one ever says money is dirty but the means of making money affects our attitudes on how to make the money anyways because we are sensitive to what people think about us and what my neighbors will think if I tell them that I am a waste worker.”P26: Key Informant Kiteezi

Routine and Script

Norms

“The way we handle the different types of solid waste generated from our homes is not very good. Solid waste segregation and recycling is not yet a common practice since we have not been sensitized on how to handle it properly. Even if there are some trainings on solid waste segregation and recycling, the places where we stay, are full of people who are mobile and keep on shifting thus making it hard for the replication of the trainings since you can’t keep training individuals. Nevertheless, we need to be trained and sensitized in the way to handle our waste”P6: FGD participant Kasubi-Residential

Objects and Infrastructure

“First of all, the capacity to do that, for you to segregate, you must be having the mechanism, you need to have proper containers, and so if you don’t have containers, you cannot segregate. Secondly, you must be having man power to do that on almost every time and the ability to hire somebody to always do that.”P19: Key informant government parastatal

“Poverty, majority of the people would have liked to have extra bins for waste storage and segregation but cannot afford given the cost implication it has on their budgets.”P30: Key Informant Kasubi

Touch Points

“In this market we have a department that is in charge of media and any other communication that people need to receive and in this we make use of our big megaphone installed up there which reaches a bigger population. Therefore, any communication regarding the need, time and the like of doing things as far as sanitation is concerned is always handled and communicated timely by the concerned persons since we have all the departments.”P23: Key Informant Market leader

3.2.5. Context-Related Drivers

“...I know Usafi market, the food section has done so well at diverting the green wastes. They do it perfectly, they employ someone to make sure that no polythene bags go in and the Coca-Cola company is also doing well in recycling, they are trying to buy back all the plastics they put out. But of course, they don’t do it very aggressively, they do it slowly, they are not pushing it too much.”P26: Key informant Kiteezi

“That issue of sorting rubbish, we tried to do it since we got trainings from different organizations. Some people have tried sorting plastic bottles. We had got lucky when coca cola, Pepsi Company and Riham companies intervened to get us places to dispose the plastics. But this other decomposing rubbish was collected, especially during this time of COVID and people started making briquettes out of them. However, those are just a few of them. So, it needs a lot more effort and I request more organizations to come out and train the people. We can reduce the garbage if they train more people.”P35: participant FGD Kamwokya

“People are learning to see the values of garbage. They are seeing waste as money e.g., bottles and AMREF is giving money to women who do recycling. They make table mats, they make tables as I told you. They also use straws to make mats. These are some of the good behavior, which some NGOs are promoting like AMREF which I said is giving them funding and these activities are now keeping children busy. You find most of them busy making briquettes for fire and even they sell”P1: Key Informant Kawempe

“To add on what has been said, we have some people that are champions in the general cleanliness. Almost all the villages in Kamwokya, the chairpersons sat and chose the champions of hygiene and these are the ones that should be given any information concerning the hygiene of the community.”P35: participant FGD Kamwokya

“People can’t sort the waste because it is not yet a policy. It is a by the way that is why it is done in places of Kololo. First of all, sorting is tiresome and they have nowhere to keep it. The containers are expensive and you are telling the person to keep garbage for three days. Even the sorting material should be labelled properly and given for free alike anywhere in the world. Garbage containers are given by municipalities, companies or government. So, minus that don’t even think of any intervention.”P7: Key informant, private solid waste collection company

“Secondly, we need to ensure proper enforcement of the law, there are byelaws and ordinances of solid waste management but those responsible especially KCCA, if they are very serious, they can wipe out all bad vices in the city. The laxity may be due low capacity technically and have no man power or money to be everywhere but even the little they have if they were deploying it well, it could achieve a lot.”P19: Key informant, government parastatal

“The main challenge especially in Kampala is political interference, sometimes we put ordinance but politicians come in and interfere with everything in the community... Politicians usually undo this work of community sensitization on proper waste management by giving their other views such as promising free garbage collection by government which never comes to pass.”P1: Key informant Kawempe

“Another challenge we have is that the Ministry Z is silent about solid waste management. Because we have an environmental health division but they are a bit quiet on solid waste management. You talk about excreta management that one is very loud, they bring so many projects e.g., CLTS, SAN marketing, PHAST etc. But that component of solid waste is not so much pronounced then number two; we tend to put emphasis on hardware as far as solid waste management is concerned, we look at picking and taking but that people are not aware, we should first make sure that people know the bad part of the waste, if I accumulate garbage, what are the health issues.”P1: Key informant Kawempe

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dladla, I.; Machete, F.; Shale, K. A review of factors associated with indiscriminate dumping of waste in eleven African countries. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2016, 8, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, D.; McCormick, M.; Mugero, C.; Skinnider, M.; Bek’Obita, D.D.; Okware, S.I. Epidemiology of cholera outbreak in Kampala, Uganda. East Afr. Med. J. 2000, 77, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nnaji, C.C.; Utsev, J.T. Climate Change and Waste Management: A Balanced Assessment. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2011, 13, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Asnani, P.; Zurbrugg, C.; Anapolsky, S.; Mani, S.K. Improving Municipal Solid Waste Management in India: A Sourcebook for Policymakers and Practitioners; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yousif, D.F.; Scott, S. Governing solid waste management in Mazatenango, Guatemala: Problems and prospects. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2007, 29, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L.; Joseph, J.B. Demand management—A basis for waste policy: A critical review of the applicability of the waste hierarchy in terms of achieving sustainable waste management. Sustain. Dev. 2000, 8, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, A.; Mahmood, A.; Abdul Aziz, H.; Robinson, G.M. Investigating Households Attitude Toward Recycling of Solid Waste in Malaysia: A Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2009, 3, 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Matter, A.; Dietschi, M.; Zurbrügg, C. Improving the informal recycling sector through segregation of waste in the household–The case of Dhaka Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Li, B.; Zhou, T.; Wanatowski, D.; Piroozfar, P. An empirical study of perceptions towards construction and demolition waste recycling and reuse in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, S.; Gupta, A.; Desai, D. Recycling and reuse of construction and demolition waste for sustainable development. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sin-Yee, T.; Sheau-Ting, L. Attributes in Fostering Waste Segregation Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2016, 7, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, M. Household knowledge, attitudes and practices in solid waste segregation and recycling: The case of urban Kampala. Zamb. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Komakech, A.J.; Banadda, N.E.; Kinobe, J.R.; Kasisira, L.; Sundberg, C.; Gebresenbet, G.; Vinnerås, B. Characterization of municipal waste in Kampala, Uganda. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2014, 64, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aunger, R.; Curtis, V. Behaviour Centred Design: Towards an applied science of behaviour change. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UBOS. The National Population and Housing Census 2014—Main Report; Uganda Bureau of Statistics: Kampala, Uganda, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, A.; Myers, I.; Namuli, H. Urban informality and vulnerability: A case study in Kampala, Uganda. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulabako, R.N.; Nalubega, M.; Wozei, E.; Thunvik, R. Environmental health practices, constraints and possible interventions in peri-urban settlements in developing countries—A review of Kampala, Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2010, 20, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssekamatte, T.; Isunju, J.B.; Balugaba, B.E.; Nakirya, D.; Osuret, J.; Mguni, P.; Mugambe, R.; van Vliet, B. Opportunities and barriers to effective operation and maintenance of public toilets in informal settlements: Perspectives from toilet operators in Kampala. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019, 29, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.G. Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.; Thorseth, A.H.; Dreibelbis, R.; Curtis, V. The determinants of handwashing behaviour in domestic settings: An integrative systematic review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 227, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, J.B.; Chipungu, J.; Bosomprah, S.; Aunger, R.; Curtis, V.; Chilengi, R. Effect of a behaviour change intervention on the quality of peri-urban sanitation in Lusaka, Zambia: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e187–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, O.P.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Cairncross, S.; Cavill, S.; Curtis, V. Trial of a novel intervention to improve multiple food hygiene behaviors in Nepal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; Schmidt, W.; Sahanggamu, D.; Fatmaningrum, D.; van Liere, M.; Curtis, V. Can gossip change nutrition behaviour? Results of a mass media and community-based intervention trial in East Java, Indonesia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, K.; Chipungu, J.; Curtis, V.; Schmidt, W.P.; Siwale, Z.; Mudenda, M.; Chilekwa, J.; Lewis, J.J.; Chilengi, R. Multiple behaviour change intervention for diarrhoea control in Lusaka, Zambia: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e966–e977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunger, R.; Curtis, V. BCD Checklist: Behaviour Centred Design Resources; London School of Hygiene: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, I.; Oberender, A.; Brooking, A. Source separation and potential re-use of resource residuals at a university campus. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 40, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.K.A.; Abdullah, S.H.; Manaf, L.A. Community participation on solid waste segregation through recycling programmes in Putrajaya. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 30, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukama, T.; Ndejjo, R.; Musoke, D.; Musinguzi, G.; Halage, A.A.; Carpenter, D.O.; Ssempebwa, J.C. Practices, Concerns, and Willingness to Participate in Solid Waste Management in Two Urban Slums in Central Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 2016, 6830163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowski, M.; Hanley, N.; Nyborg, K. Social norms, morals and self-interest as determinants of pro-environment behaviours: The case of household recycling. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 66, 647–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videras, J.; Owen, A.L.; Conover, E.; Wu, S. The influence of social relationships on pro-environment behaviors. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012, 63, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickmeyer, D. Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattoua, M.G.; Al-Khatib, I.A.; Kontogianni, S.; Management, W. Barriers on the propagation of household solid waste recycling practices in developing countries: State of Palestine example. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkolnchaiarunya, J. Promoting a community-based solid-waste management initiative in local government: Yala municipality, Thailand. Habitat Int. 2005, 29, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Smith, S.R.; Fowler, G.; Velis, C.; Kumar, S.J.; Arya, S.; Rena Kumar, R.; Cheeseman, C. Challenges and opportunities associated with waste management in India. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. Understanding household waste separation behaviour: Testing the roles of moral, past experience, and perceived policy effectiveness within the theory of planned behaviour. Sustainability 2017, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciol, A.; Montinari, N.; Piovesan, M. Do not trash the incentive! Monetary incentives and waste sorting. Scand. J. Econ. 2015, 117, 1204–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheau-Ting, L.; Sin-Yee, T.; Weng-Wai, C. Preferred attributes of waste separation behaviour: An empirical study. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylä-Mella, J.; Keiski, R.L.; Pongrácz, E. Electronic waste recovery in Finland: Consumers’ perceptions towards recycling and re-use of mobile phones. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okot-Okumu, J. Solid waste management in African cities-East Africa. In Waste Management—An Integrated Vision; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gotame, M. Community Participation in Solid Waste Management; The University of Bergen: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vassanadumrongdee, S.; Kittipongvises, S. Factors influencing source separation intention and willingness to pay for improving waste management in Bangkok, Thailand. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Zhang, W.; Che, Y.; Feng, D. Municipal solid waste source-separated collection in China: A comparative analysis. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavioural Determinants Defined by the BCD Framework | Questions that Were Considered | |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Physical | What is the physical setting like? What things in the physical environment enable or prevent SWSR? Is SWSR affected by the physical or built environment including climate/weather and geography? |

| Social | Does the social environment (relationships, networks and organisations) affect SWSR? | |

| Brains | Executive | Do the target communities know the need and benefits for SWSR and how it should be performed? |

| Motivated | Is SWSR rewarding? Does disgust (the desire to avoid cues to sources of infection), affiliation (the desire to fit in with others) and nurture (the desire to care for your child). | |

| Reactive | Is SWSR habitual? Did it become a norm? | |

| Body | Characteristics | Are there Socio-demographic characteristics (gender, wealth, age, education and employment etc) that influence SWSR? |

| Senses | The sensory perceptions (smells of solid waste and sight) that may influence SWSR? | |

| Capabilities | Are there individual skills required to segregate and recycle waste? Do individuals perceive themselves to have the ability to segregate and recycle waste? | |

| Behaviour settings | Stage | Where does SWSR take place? Are there concerns related to the specific physical spaces where SWSR take place? |

| Roles | What is the role played by the community in SWSR and how does it relate to roles played by the authorities in charge of waste management? Are there ways in which an individual’s role, identity or responsibilities influence their SWSR practices? | |

| Routine and script | How does the daily routine of activities undertaken by the community influence SWSR? | |

| Norm | What SWSR behaviour is the community expected to have? Is SWSR a common practice in the community (descriptive norm); is SWSR part of some individual’s role and normal behaviour (personal norm); is SWSR socially approved of (injunctive norm); and is SWSR practiced by individual’s ‘valued others’ (subjective norm) | |

| Objects and infrastructure | Are there objects needed by the community to do SWSR available? What infrastructure needs to be in place to perform SWSR? | |

| Touch points (Communication channels) | Are there mechanisms through which community members are receive information/messages related to SWSR? Which mechanism are these? | |

| Context | Programmatic, political, economic, social, and legislative framework | Are there active SWSR programs in the study area? Are there political or historical events that have influenced SWSR programs in this area? Are there laws and policies about SWSR? Are there opportunities and gaps in the legislation? |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n = 63) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–29 | 11 | 17.46 | |

| 30–39 | 28 | 44.44 | |

| 40–49 | 16 | 25.40 | |

| Over 50 | 8 | 12.70 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 27 | 42.86 | |

| Female | 36 | 57.14 | |

| Highest level of education | |||

| No formal education | 1 | 1.59 | |

| Primary | 26 | 41.27 | |

| Secondary | 32 | 50.79 | |

| Tertiary | 4 | 6.35 | |

| Religion | |||

| Anglican | 25 | 39.68 | |

| Catholic | 15 | 23.81 | |

| Muslim | 9 | 14.29 | |

| Pentecostal | 14 | 22.22 | |

| Occupation | |||

| Employed | 12 | 19.05 | |

| Self-employed | 8 | 12.70 | |

| Business | 29 | 46.03 | |

| Casual labourer | 5 | 7.94 | |

| Student | 2 | 3.17 | |

| No employment | 7 | 11.11 |

| Themes | Subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Environment related drivers | Physical environment | The siting and construction of houses in the study areas is poorly planned |

| The houses are so congested for SWSR to happen | ||

| No physical space for putting waste segregation equipment | ||

| Social environment | Encouragement to segregate and recycle as a result of peer influence | |

| Waste segregators and recyclers influence some people staying in their geographical areas. | ||

| Collective actions which promote learning and behavior change | ||

| Brains related drivers | Executive brain | Awareness on issues related to solid waste segregation and recycling |

| Motivated brain | Appropriate waste segregation and recycling is associated with rewards such as money, a clean and safe environment | |

| Body related drivers | Socio-demographic characteristics | Segregation of waste can be easily performed in upper income residences, which have space and better roads |

| SWSR can easily be performed by institutions and middle-income people. | ||

| Human senses | Smells hinder people from segregating and recycling waste. | |

| Capabilities | Waste segregation and recycling requires special skills | |

| Behaviour setting drivers | Stage | Presence of bins for waste segregation |

| Roles | Individuals (especially women and children) play a critical role in waste segregation and recycling | |

| Companies (waste companies and NGOs) play a role in waste segregation and recycling | ||

| Routine and script | The SWSR routine involves cleaning and sorting waste into useful streams | |

| Norms | SWSR is not norm | |

| Objects and infrastructure | SWSR requires infrastructure such as waste bins | |

| Touch points | SWSR requires behavior change communication through mega phones, loud speakers, community meetings, and door to door visits | |

| Context related drivers | Policy framework | No policy and by-laws on SWSR |

| Stakeholders | Stakeholders critical in SWSR |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mugambe, R.K.; Nuwematsiko, R.; Ssekamatte, T.; Nkurunziza, A.G.; Wagaba, B.; Isunju, J.B.; Wafula, S.T.; Nabaasa, H.; Katongole, C.B.; Atuyambe, L.M.; et al. Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710947

Mugambe RK, Nuwematsiko R, Ssekamatte T, Nkurunziza AG, Wagaba B, Isunju JB, Wafula ST, Nabaasa H, Katongole CB, Atuyambe LM, et al. Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710947

Chicago/Turabian StyleMugambe, Richard K., Rebecca Nuwematsiko, Tonny Ssekamatte, Allan G. Nkurunziza, Brenda Wagaba, John Bosco Isunju, Solomon T. Wafula, Herbert Nabaasa, Constantine B. Katongole, Lynn M. Atuyambe, and et al. 2022. "Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710947

APA StyleMugambe, R. K., Nuwematsiko, R., Ssekamatte, T., Nkurunziza, A. G., Wagaba, B., Isunju, J. B., Wafula, S. T., Nabaasa, H., Katongole, C. B., Atuyambe, L. M., & Buregyeya, E. (2022). Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710947