Recruiting Participants in Vulnerable Situations: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Recruitment Process in the EFFICHRONIC Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

- Could you start by telling me how was the process of recruitment of stakeholders in your context…

- How were all relevant stakeholders proposed/found for the recruitment work?

- o

- Whom did you contact?

- o

- How did it go?

- o

- or …

- Which strategies have been most effective in identifying and involving these stakeholders? And the difficulties?

- Which strategies have been most effective in recruiting vulnerable people (patients and caregivers)?

- Based on your experience, or according to what stakeholders have said: Have there been difficulties in recruiting users? What could have made it challenging?

- Have the tools and procedures designed to recruit them been useful? What could be im-proved? What would you change?

- What have you learnt from this experience of collaborating with local stakeholders for the recruitment of vulnerable populations?

- How has your relationship with the stakeholders changed after engaging in this process?

- How would you think you would do the recruitment process again after this experience?

- Would you like to add something about the topic that was not covered in the interview?

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

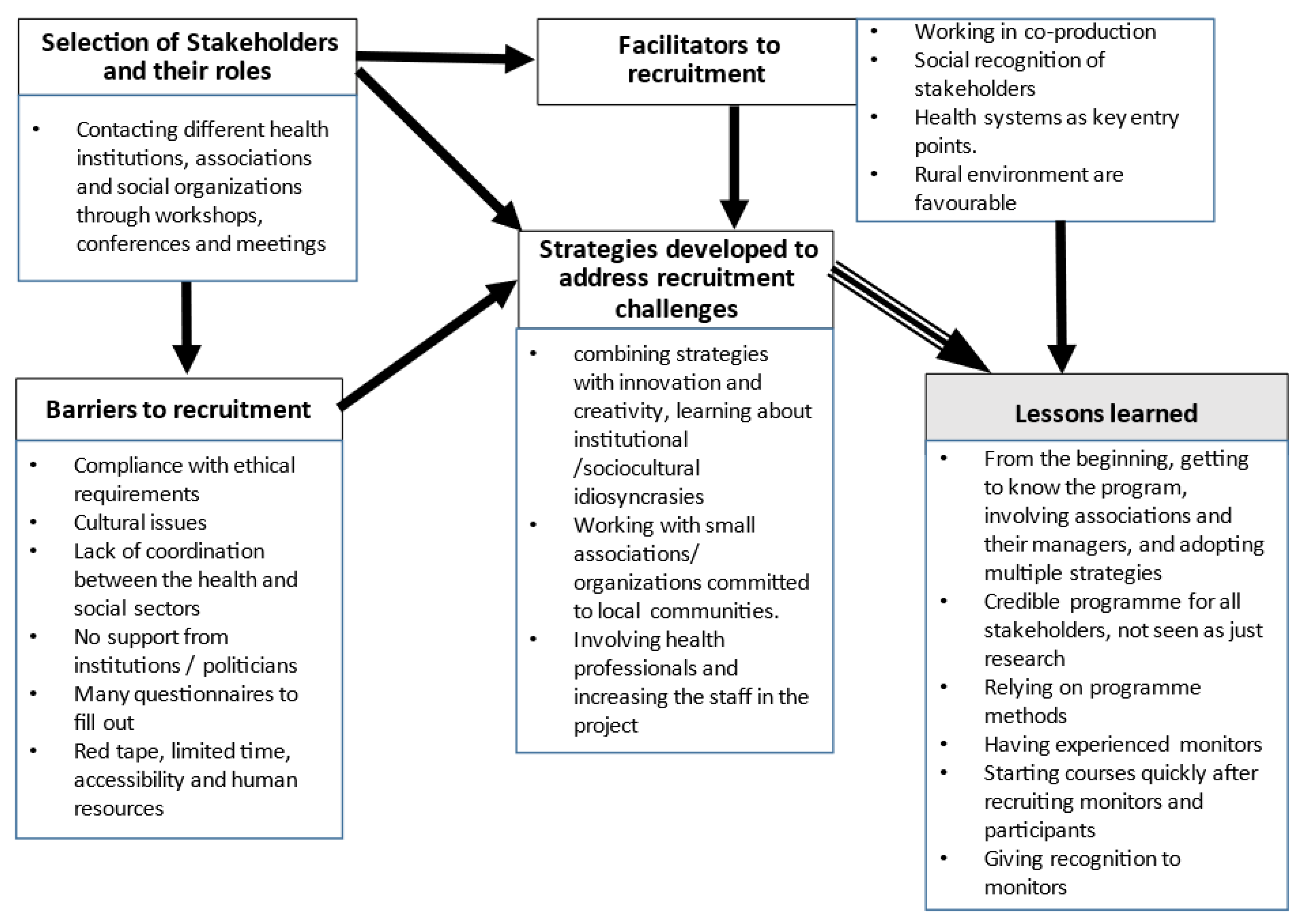

3.1. Stakeholder Recruitment Strategies

“We contacted many patient associations for the first time. … political institutions at the level of the region, or department, or the ministry of public health … we started to meet with them individually and we talked to them about the project” (P1).

“That we go and present it somewhere and they see how enthusiastic we are, even though it is a presentation that I strongly believe in it and that this can work. … and this push can be given by the doctor or the nurses … and you go because someone told you well. However, it does have to come out of emotion” (P2).

“We agreed what vulnerability looked like in [name of country] and how they would approach vulnerable people, and how they were getting them involved in the programme. So it was very much done with them. Not just us telling them, it was done with them. A co-production we called it” (P3).

“There are the councillors who contact us and act as intermediaries with the associations. Furthermore, if you act as a liaison, it is a different story because the municipality also finances the associations and therefore, a more potent synergy is created. The municipality acts as a spokesperson, the associations respond more easily, and doors open more easily. You can contact, you can organise things more easily” (P4).

“I was searching for organisations like this, through internet and my network, and I had a list of 3 organisations like this. Additionally, this one happened to be around the corner from my home. So I just contacted them” (P5).

3.2. Facilitators to Recruitment

“it was essential [the co-production], because they are the experts, not us, we are the experts in the quality, they are the experts in the [Stanford COURSE], so yes, we developed it with them, then with the concept agreed, it became the criteria for the project” (P3).

“the study’s Principal Investigator spoke about the project at many important institutional events, so it was taken to various policy and working fields, even at the regional level” (P4).

“Muslim animator, (…), also works for the (health institution) because she is a nurse, and the Health Region told her to do it” (P1).

“Associations like [name of association], for example, a bit linked to the church, and they have a fairly loyal audience there” (P2).

“health staff who already dealt with chronic conditions and therefore worked in laboratories where there were caregivers, (…), so they knew the reality and were purely self-motivated, even personal interest, that some, being chronic or caregivers of parents with major chronic diseases, wanted to be involved” (P4).

“In rural areas, there is not so much, and so in rural areas, where we are, it is much easier because we don’t have to fight or compete …” (P2).

“The people who came to me are the ones with fibromyalgia because they don’t know anything and don’t know where to go” (P1).

3.2.1. Monitor Recruitment Strategies

“for people at the hospital we just recruited through the Intranet, or facebook, we have an internal facebook page, we have screensavers …” (P5).

“That girl who is a judge, for example, is the sister of another monitor, (…) and she said “well, I’m interested in that too” (…) It’s been a bit like that, like a snowball. And it has been like that… well, the training is open to health workers, but on the other hand, it is open to different types of people” (P2).

“I conducted interviews with the participants [monitors] who I thought were more communicative and willing to do courses, and [selected them also] based on the personality characteristics that emerged in the first course” (P4).

“A nurse who conducts a workshop with me now does it during her working hours. And when the workshop is after hours, she gets compensated with time off work” (P2).

“(…) among them there are people from prisons, social workers from day centres, whom we had not contacted, and there are, for example, people from NGOs that we went to introduce them to the programme, and they said, “oh well, I’d like to do the training”. Then there are people … like a judge, a retired doctor, in other words, a group of committed people, who want to do this in their free time” (P2).

3.2.2. Participant Recruitment Strategies

“one way to recruit citizens was also through our hospital, through the intranet…” (P5).

“The doctor or the nurses can give this push, and they say, “Hey, I think this could be good for you”, and they push them, and you go because someone told you so” (P2).

“lots of their recruitment is done through the third sector, voluntary sector, through their own communities, not through the health route” (P3).

“Also we did advertising in a [city] newspaper, in 2 different moments: one that goes door-to-door, they put it in the mail boxes, and we did it there twice, once in the summer break, it was successful” (P5).

“so we did another advertisement in the same paper in September but responses are still coming in, so I don’t know, I don’t think it will be as successful as during the summer, so now we will try another newspaper, that is specifically for age 55+, but this is spread through public places […] like in libraries, social work organisation, swimming pool, supermarkets. And I had never heard about it, and since I [‘ve] heard about it, I see it everywhere” (P5).

“we continued organising, sending newsletters, initiatives to associations, inviting the population” (P4).

“It could be anyone [employee from the municipality], we recruited really broad. It was on their intranet, it was really the same, because now we are only talking about the train the trainers, but at the same time we were also recruiting citizens” (P5).

“The one with diabetes, the presenter, was a Muslim, and that’s why they came because they were his networks” (P1)

“It’s the most direct word of mouth that works. So, either from a health professional or from a friend or acquaintance, who explains to them what it’s all about” (P4).

“We wanted to see where the most vulnerable population resides [in the region], and a mapping was done, so great, and we started with the most vulnerable areas” (P2).

“we agreed what vulnerability looked like in [name of country] and how they would approach vulnerable people, and how they were getting them involved in the programme. So it was very much done with them. Not just us telling them, it was done with them. A co-production we called it” (P3).

3.3. Barriers to Recruitment

“We started much later with the courses because, as a centre (in a country), as a hospital, we need the approval of the ethics committee” (P4).

“to talk about an ethnic minority, in (a country) is forbidden by the constitution” (P1).

“[what] we haven’t done is go for [implementing the programme in] prisons. Be cause ethically [it] would be practically impossible to do in (a country)” (P3).

“There are two types of associations or groups, either social or health, it is impossible to find one that does both. So when you go to a health association, like a patients’ association, they don’t have vulnerable people, because whoever does this action, to join a patients’ association, is not vulnerable” (P1).

“people are moving on to other things, like into more digital based programmes as opposed to group-based programmes. (…) it’s run locally by mainly voluntary sector organisations, struggling for funding to be honest at the moment, and the country funding are being cut” (P3).

“getting people to fill in the questionnaire is … Is proving quite hard. One of the things we realised of course is that people already complete questionnaires for the programme providers [who organise the courses and recruit participants]” (P3).

“At 14.30, the older people are asleep … and so … yes, we finished it, but with great difficulty, we started with 10, and we didn’t even have 5 [at the end]. It was really exhausting” (P4).

“In the first wave for the animators [monitors], we were actually very selective because we were afraid we would not find them, because in other countries there are no such programmes, but here, even if you talk about self-management of the disease… it is the basis of all the programmes, there are so many” (P1).

3.3.1. Difficulties in Recruiting Monitors

“The first problem that the animators [monitors] wanted to get paid” (P1).

“Many people said that they could no longer take part. Some because of illness problems, others because of important family situations that had arisen in those months” (P4).

3.3.2. Difficulties in Recruiting Participants

“It’s very old people, people who live alone, and frankly distrustful, so you called them, and they just didn’t trust that it was that good “you’re really going to give me a workshop, for free…” (P2).

“They [migrants] are afraid that the police come while we give workshops” (P2).

“Because they are the people [in marginalised situations] who are less involved in the advocacy and outreach meetings that the hospital offers. Furthermore, they are the people who have the most problems, even if they live in situations of isolation. So then how do we reach them? (P4).

3.4. Strategies Developed to Address Recruitment Challenges

“I think it has to be a combination, because any strategy is difficult, so we need a combination in order to get numbers [reaching enough participants]. But I hope, now we started flyering, so we have our hopes up again, but we know from experience” (P5).

“In urban areas, thank God or thanks to the fact that there is a history, we now have an associative fabric and a community fabric in which you enter, for example, a social centre and you have Tupperware cookery classes, patchwork classes, belly dancing classes, classes of whatever you want, they have, so to speak, a wide range of ways of spending the afternoon” (P2).

“For me, it’s very difficult to do the intake. For the volunteer agency, they know the people, also, so it’s easier for them” (P5).

“Now it is easier, under the patronage of the municipality of (name of the city), because we are stronger, sponsored by the municipality of (name of the city), (…). So, regarding citizens, we can reach more people” (P4).

“The first thing we did was to get there and have them take off their white coats, we literally took off their white coat and sat them down to shake them a little bit from the mega interventionism that you have in a hospital and shake them up, so that they would think a little bit like normal people, and like someone who has a mother and a father” (P2).

“We had another learning… in our team group, now we have 3 people working for effichronic on recruitment and also to keep in contact with the trainers, and for me this is also a good learning experience, to guide them [the new co-workers]” (P5).

3.5. Lessons Learned

“Until you attend an EFFICHRONIC course, you don’t know what is actually happening” (P4).

“In an ideal world, I’d have been involved from the beginning and work it all through. We really had to move very quickly to get people agree. So if I had to do it again, I would start it earlier” (P3).

“I was frightened about the commitment, in the sense that … I mean … joining the project also asked them for a commitment to promote and engage people. So, maybe some associations, rather than sending the message that this project exists, have not been very active in recruiting [participants] among their members” (P4).

“And with the participants, the jewel in the crown, so to speak, you are not paid anything. But you get the satisfaction of how people change and how they pick it up, and that’s good” (P2).

“I appreciate personally that I came to learn about this world that is so close to my world, you don’t see it if you are not in it, or working in it. So for me that was really nice, and also [I learnt that] you need another approach, you need to approach people differently …” (P5).

“Last year we conducted a lot of workshops, and the more I ran, the more I got out of the way to let them act. Because it works …you see how well they [the sessions of the programme] are constructed …and it works because it is well built…” (P2)

“We think it’s the heart of the programme, learning from others who have a long term condition…” (P3).

“We trained them in November, but the courses started almost a year later, in September, because apart from those pilot courses in May, then between the ethics committee, but also the project itself with the leader [monitor], the partners, they all left later, in 2018 and, therefore, in a year and more, situations change” (P4).

“really aggressive in the first week, so poster, newspaper, flyers, so you have a lot at once” (P5).

“Both the directors and the association tell us that at the moment [if participants have to reach distant areas of the city, because it is hot] there would be nobody” (P4).

“I would establish a budget for the directors [EFFICHRONIC coordinators], because even though … we did it voluntarily, (…). in reality, it is a big commitment, so even recognition for the directors is a motivational lever” (P4).

“(…) that time they put in would be reverted to days off work. Right now, we are looking at people who don’t have a job in the health system because they are patients or so on, so they can be given money, we don’t know how much yet” (P5).

4. Discussion

Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Definition of Responsible Innovation [Internet]. René von Schomberg. 2012. Available online: https://renevonschomberg.wordpress.com/definition-of-responsible-innovation/ (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- AQuAS. ¿Cómo Medir la Participación en Investigación de los Actores del Sistema? Revisión de la literatura. Barcelona: AQuAS; 2018. [Internet]. Available online: https://aquas.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/aquas/publicacions/2018/como_medir_participacion_investigacion_saris1_aquas2018es.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- European Commission. Participatory Approaches and Social Innovation in Culture|Programme|H2020|CORDIS|European Commission [Internet]. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/programme/id/H2020_CULT-COOP-06-2017 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- National Institute for Health Research. About INVOLVE—INVOLVE [Internet]. Available online: https://www.invo.org.uk/about-involve/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Tan, S.S.; Pisano, M.M.; Boone, A.L.; Baker, G.; Pers, Y.-M.; Pilotto, A.; Valsecchi, V.; Zora, S.; Zhang, X.; Fierloos, I.; et al. Evaluation Design of EFFICHRONIC: The Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (CDSMP) Intervention for Citizens with a Low Socioeconomic Position. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, E1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Self-Management Resource Center. History of Standford Self-Management Programs. [Internet]. Available online: https://www.selfmanagementresource.com/about/history/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Griffiths, C.; Foster, G.; Ramsay, J.; Eldridge, S.; Taylor, S. How effective are expert patient (lay led) education programmes for chronic disease? BMJ 2007, 334, 1254–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.P.; Anderson, J.K.; Wallace, L.M.; Kennedy-Williams, P. Evaluation of a self-management programme for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir. Dis. 2014, 11, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelt, A.; Continente, X.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Monge, S.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Perez, G.; Borrell, C. La vigilancia de los determinantes sociales de la salud. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz Roja Española. Informe Anual Sobre la Vulnerabilidad Social. Madrid: Cruz Roja Española; 2007 [Internet]. Available online: https://www2.cruzroja.es/documents/5640665/13549746/2007+Informe+sobre+la+vulnerabilidad+social.pdf/a8ccc1fb-18b0-6bfe-610a-0b8865ce197d?t=1556612297230 (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- EFFICHRONIC. D4.2. Ethics, Methodologies and Standards. WP4—Stratification: Vulnerability Multidimensional Analysis. V4. May 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bb15c837&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Rendle, K.A.; Abramson, C.M.; Garrett, S.B.; Halley, M.C.; Dohan, D. Beyond exploratory: A tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callejo Gallego, J. Observación, entrevista y grupo de discusión: El silencio de tres prácticas de investigación. Revista Española de Salud Pública 2002, 76, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valles, M.S. Entrevistas Cualitativas; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid. Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Dadich, A.; Stout, B.; Plath, D. Clarifying the role of belief-motive explanations in multi-stakeholder realist evaluation. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 80, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagosh, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Pluye, P.; Salsberg, J.; Bush, P.; Henderson, J.; Sirett, E.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Herbert, C.P.; et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 311–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, G.K.; Shepherd, J.; Pickett, K.; Griffiths, G.; Wyatt, J.C. Digital tools for the recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: A systematic map. Trials 2020, 21, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes-Morley, A.; Hann, M.; Fraser, C.; Meade, O.; Lovell, K.; Young, B.; Roberts, C.; Cree, L.; More, D.; O’Leary, N.; et al. The impact of advertising patient and public involvement on trial recruitment: Embedded cluster randomised recruitment trial. Trials 2016, 17, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, A.; Ogden, M.; Cooper, C. Planning and enabling meaningful patient and public involvement in dementia research. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Caffrey, L.; McKevitt, C. Barriers and opportunities for enhancing patient recruitment and retention in clinical research: Findings from an interview study in an NHS academic health science centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2015, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L.; Van Damme, P.; Vandermeulen, C.; Mali, S. Recruitment barriers for prophylactic vaccine trials: A study in Belgium. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6598–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, S.; Greco, B.L.; Biglan, K.; Kopil, C.M.; Holloway, R.G.; Meunier, C.; Simuni, T. Increasing Efficiency of Recruitment in Early Parkinson’s Disease Trials: A Case Study Examination of the STEADY-PD III Trial. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C.B.; LeRoy, L.; Donahue, S.; Apter, A.J.; Bryant-Stephens, T.; Elder, J.P.; Hamilton, W.J.; Krishnan, J.A.; Shelef, D.Q.; Stout, J.W.; et al. Enrolling African-American and Latino patients with asthma in comparative effectiveness research: Lessons learned from 8 patient-centered studies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Gallardo, P.; Cassetti, V.; Boone, A.L.D.; Pisano-González, M.M. Recruiting Participants in Vulnerable Situations: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Recruitment Process in the EFFICHRONIC Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710765

Serrano-Gallardo P, Cassetti V, Boone ALD, Pisano-González MM. Recruiting Participants in Vulnerable Situations: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Recruitment Process in the EFFICHRONIC Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710765

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Gallardo, Pilar, Viola Cassetti, An L. D. Boone, and Marta María Pisano-González. 2022. "Recruiting Participants in Vulnerable Situations: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Recruitment Process in the EFFICHRONIC Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710765

APA StyleSerrano-Gallardo, P., Cassetti, V., Boone, A. L. D., & Pisano-González, M. M. (2022). Recruiting Participants in Vulnerable Situations: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Recruitment Process in the EFFICHRONIC Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710765