Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

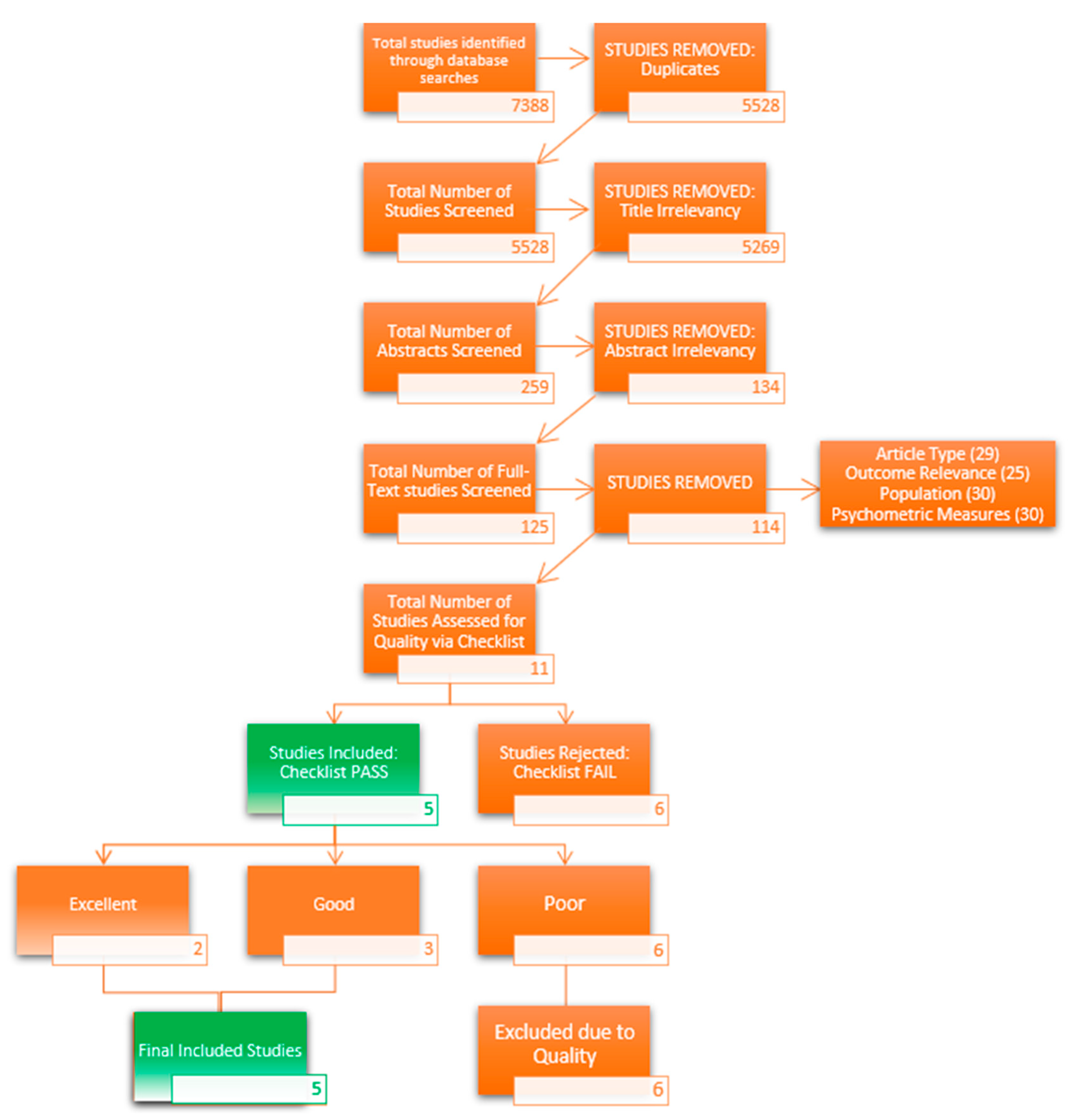

2. Materials & Methods

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1: Burnout in Correctional Settings

3.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Methodological Quality

Sources of Occupational Stress

Characteristics of Included Studies

Measurement of Burnout

Occupational Stressor Impact

- Intrinsic to Job Role

- Role in the Organization

- Career Development

- Relationships at Work

- Organizational Structure/Climate

- Individual and Extra-Organizational

3.2. Stage 2: Correctional Burnout Interventions

3.2.1. Methodological Quality

3.2.2. Assessment of Methodological Quality

3.2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2.4. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Review of Interventions

3.4. Stage 1 & 2 Integration

3.4.1. Specific Populations and Burnout

Corrections Staff

Correctional Mental Health Providers

Psychiatric Inpatient Facility Professionals

Law Enforcement

4. Conclusions

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Job burnout: How people cope. Public Welf. 1978, 36, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Burnout. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, L.V.; Heinemann, T. Burnout research: Emergence and scientific investigation of a contested diagnosis. Sage Open 2017, 7, 2158244017697154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S. Causes and management of stress at work. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, L.R. Occupational stress management: Current status and future directions. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.; Igoumenou, A.; Mortlock, A.M.; Gupta, N.; Das, M. Work-related stress in forensic mental health professionals: A systematic review. J. Forensic Pract. 2017, 19, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, H.; Giddings, M.M. Hidden trauma victims: Understanding and preventing traumatic stress in mental health professionals. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2017, 15, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Worthington, R.; Gredecki, N.; Wilks-Riley, F.R. The relationship between trust in work colleagues, impact of boundary violations and burnout among staff within a forensic psychiatric service. J. Forensic Pract. 2016, 18, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Henning, R.; Cherniack, M. Correction workers’ burnout and outcomes: A bayesian network approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keinan, G.; Malach-Pines, A. Stress and burnout among prison personnel: Sources, outcomes, and intervention strategies. Crim. Justice Behav. 2007, 343, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyers, M.P.; Flanagan, M.E.; Firmin, R.; Rollins, A.L. Clinicians’ perceptions of how burnout affects their work. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.G.; Atnas, C.I.; Ryan, P.; Ashby, K.; Winnington, J. Whole team training to reduce burn-out amongst staff on an in-patient alcohol ward. J. Subst. Use 2010, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Å.; Lundberg, U.; Farbring, C.Å.; Källmén, H.; Forsberg, L. The feasibility and potential of training correctional officers in flexible styles of communication to reduce burnout: A multiple baseline trial in real-life settings. Scand. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, A.; Balzola, M.A.; Gatto, R.; Soresini, A.; Mabilia, D.; Poletti, S. Compassion-oriented mindfulness-based program and health professionals: A single-centered pilot study on burnout. Eur. J. Ment. Health 2019, 14, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; Bergman, A.L.; Green, K.; Dapolonia, E.; Christopher, M. Relative impact of mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological flexibility on alcohol use and burnout among Law enforcement officers. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, M.A.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Sansó, N. The impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on the quality of life of Spanish national police officers. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wampole, D.M.; Bressi, S. Exploring a social work lead mindfulness-based intervention to address burnout among inpatient psychiatric nurses: A pilot study. Soc. Work Health Care 2020, 59, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagaric, B.; Markanovic, D. Application of stress-focused mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with prison system staff. Kriminol. Soc. Integr. 2021, 29, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, E. Development, delivery, and evaluation of a pilot stress reduction, emotion regulation, and mindfulness training for juvenile justice officers. J. Juv. Justice 2015, 4, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, A.L.; Kukla, M.; Morse, G.; Davis, L.; Leiter, M.; Monroe-DeVita, M.; Salyers, M.P. Comparative effectiveness of a burnout reduction intervention for behavioral health providers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 920–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Fry-Smith, A. Developing the research question. In Etext on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Information Resources; National Information Center on Health Services and Health Care Technology: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boudoukha, A.H.; Altintas, E.; Rusinek, S.; Fantini-Hauwel, C.; Hautekeete, M. Inmates-to-staff assaults, PTSD and burnout: Profiles of risk and vulnerability. J. Interpers. Violence 2013, 28, 2332–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kruis, N.E.; Kim, Y. The impact of occupational characteristics and victimization on job burnout among South Korean correctional officers. Crim. Justice Behav. 2020, 47, 905–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, A.J.; Kinman, G. Job demands, organizational justice, and emotional exhaustion in prison officers. Crim. Justice Stud. 2021, 34, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallavan, D.B.; Newman, J.L. Predictors of burnout among correctional mental health professionals. Psychol. Serv. 2013, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Wang, J.N.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. The association between work-related characteristic and job burnout among Chinese correctional officers: A cross-sectional survey. Public Health 2015, 129, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colligan, T.W.; Higgins, E.M. Workplace stress: Etiology and consequences. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2006, 21, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, M.; Leip, L. The impact of job expectations, workload, and autonomy on work-related stress among prison wardens in the United States. Crim. Justice Behav. 2019, 46, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Keena, L.D.; Haynes, S.H.; May, D.; Leone, M.C. Predictors of job stress among Southern correctional staff. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2020, 31, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, R.; Mullings, J.L.; Scarborough, K.E. Work-related stress and coping among correctional officers: Implications from organizational literature. J. Crim. Justice 1996, 24, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerley, G.D.; Burnell, J.; Holder, D.C.; Kurdek, L.A. Burnout among licensed psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1988, 19, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Hogan, N.L. Work–family conflict and job burnout among correctional staff. Psychol. Rep. 2010, 106, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savicki, V.; Cooley, E.; Gjesvold, J. Harassment as a predictor of job burnout in correctional officers. Crim. Justice Behav. 2003, 30, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.B.; Minor, K.I.; Angel, E.; Matz, A.K.; Amato, N. Predictors of job stress among staff in juvenile correctional facilities. Crim. Justice Behav. 2009, 36, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanji, B. Occupational Stress: A Review on Conceptualisations, Causes and Cure. Econ. Insights–Trends Chall. 2013, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stamn, B. The ProQOL Manual: The Professional Quality of Life Scale: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout & Compassion Fatigue/Secondary Trauma Scale; Sidram Press: Brooklandville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.M.; Aalsma, M.C.; Holloway, E.D.; Adams, E.L.; Salyers, M.P. Job-related burnout among juvenile probation officers: Implications for mental health stigma and competency. Psychol. Serv. 2015, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyi, Y.; Meredith, P.; Khan, A. Effectiveness of mindfulness intervention in reducing stress and burnout for mental health professionals in Singapore. Explore 2017, 13, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, T.; Germundsjö, L.; Åström, E. Rönnlund, M. Mindful self-compassion training reduces stress and burnout symptoms among practicing psychologists: A randomized controlled trial of a brief web-based intervention. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiopoulos, E.; Cimo, A.; Cheng, C.; Bonato, S.; Dewa, C.S. Interventions to improve work outcomes in work-related PTSD: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.S.; Hunsinger, M.; Goerling, L.; Bowen, S.; Rogers, B.S.; Gross, C.R.; Dapolonia, E.; Pruessner, J.C. Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and pre-liminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 264, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A. Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence. Subst Use Misuse 2014, 49, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Katz, J.; Wiley, S.D.; Capuano, T.; Baker, D.M.; Shapiro, S. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Nurse Stress and Burnout, Part II: A Quantitative and Qualitative Study. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2015, 19, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms: A non-randomized study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atri, A.; Sharma, M. Psychoeducation. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2007, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravits, K.; McAllister-Black, R.; Grant, M.; Kirk, C. Self-care strategies for nurses: A psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2010, 23, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güler, M. The effect of psychoeducation program on burnout levels of university students. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Derg. 2020, 16, 5524–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived stress scale. Meas. Stress A Guide Health Soc. Sci. 1994, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kriakous, S.A.; Elliott, K.A.; Owen, R. Coping, mindfulness, stress, and burnout among forensic health care professionals. J. Forensic Psychol. Res. Pract. 2019, 19, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Mao, K.; Li, C. Validation of a short-form five facet mindfulness questionnaire instrument in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heritage, B.; Rees, C.S.; Hegney, D.G. The ProQOL-21: A revised version of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale based on Rasch analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangi, R.A.; Jalbani, A. Mediation of work engagement between emotional exhaustion, cynicism and turnover intentions. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zielhorst, T.; van den Brule, D.; Visch, V.; Melles, M.; van Tienhoven, S.; Sinkbaek, H.; Schrieken, B.; Tan, E.S.-H.; Lange, A. Using a digital game for training desirable behavior in cognitive–behavioral therapy of burnout syndrome: A controlled study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.D.; van Hooff, M.L.; Guerts, S.A.E.; Kompier, M.A.J. Exercise to reduce work-related fatigue among employees. A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2017, 43, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M.; Hoge, M.A. Burnout in the mental health workforce: A review. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 37, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, B.K.; Cipresso, P.; Pizzioli, D.; Wiederhold, M.; Riva, G. Intervention for physician burnout: A systematic review. Open Med. 2018, 13, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.; Bond, F.W.; Flaxman, P.E. The value of psychological flexibility: Examining psychological mechanisms underpinning a cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for burnout. Work Stress 2013, 27, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puolakanaho, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Kinnunen, S.M.; Lappalainen, R. A psychological flexibility-based intervention for Burnout: A randomized controlled trial. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2020, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Taieb, O.; Xavier, S.; Baubet, T.; Reyre, A. The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: A systematic review. Explore 2020, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Toppinen-Tanner, S.; Seppänen, J. Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burn. Res. 2017, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Yes | |

| ☐ | Is the study relevant to the research question |

| ☐ | Diagnosis (one of the following must be checked off a ‘yes’) |

| ☐ Burnout (shows symptoms as determined by a valid psychometric measurement and/or biomedical measure) | |

| ☐ Stress (shows symptoms as determined by a valid psychometric measurement and/or biomedical measure) | |

| ☐ | Correlation (one of the following must be checked off a ‘yes’) |

| ☐ Must measure correlates of stress and/or burnout | |

| ☐ Correlates must be organizationally based | |

| ☐ | Inferential Statistics (both must be checked off as a yes) |

| ☐ Includes a control or comparison group | |

| ☐ Were the results directly linked to the aim of the study | |

| ☐ | Outcomes (must be checked off as ‘yes’) |

| ☐ Description of the how the stressor is correlated to job stress or burnout | |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Yes | |

| ☐ | Sample Population (any of the following are grounds for exclusion) |

| ☐ A group that does not consist of front-line correctional officers | |

| ☐ A group not employed in an adult correctional facility (i.e., juvenile detention center, juvenile correctional facility, treatment facility, community corrections, probation office, parole office) | |

| ☐ | No Outcomes (the following are grounds for exclusion) |

| ☐ Describes offender outcomes, prisoner mental health, prisoner stress | |

| ☐ No outcomes about the sample population | |

| ☐ | Type of Article (any of the following are grounds for exclusion) |

| ☐ non-peer-reviewed article | |

| ☐ Book review | |

| ☐ Editorial | |

| ☐ Dissertation | |

| Quality Assessment Appraisal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | |||||

| Quality of Study | Studies Evaluated | Relevance | Sample Population | Measures and Outcomes | Inferential Statistics |

| Excellent | Boudoukha et al., 2013 [27] Choi et al., 2020 [28] | Research questions are clear, comprehensive, and clinically sensible. | Selection of samples front-line correctional staff, employed in adult correctional facilities | Burnout and Stressors were measured using clearly defined, reliable, and valid instruments. Outcomes describe correlation between burnout and stressors | Results were directly linked to the aim of the study |

| Good | Clements & Kinman, 2021 [29] Gallavan & Newman, (2013) [30] Hu et al. (2015) [31] | Some evidence of unclarity, incomprehensiveness or clinical insensibility | Some evidence of unclarity in recruitment | Some evidence of unclarity and lack of psychometric data Outcome lacks complete correlation between burnout and stressors | Some evidence of unclear linkage to study aims |

| References | Sample | Burnout/Stress Instrument | Stressors and Organizational Factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boudoukha, Altintas, Rusinek, Fantini-Hauwel, & Hautekeete, (2013) [27] | 240 CorrectionStaff | Maslach Burnout Inventory—French Version—22-items | Burnout PTSD | |

| Impact of Event Scale—Revised —22-items | Inmate-to-staff assaults Relationships at work | |||

| Victimization Index: Inmate-to-Staff Assaults Questionnaire—6-items | Exposure to traumatic event Victimization (direct & indirect) Relationships at work | |||

| Stress Questionnaire—12-items | Overall stress Relationships at work | |||

| Choi, Kruis, & Kim, Y. (2020) [28] | 269 CorrectionOfficers | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Korean Version—22-items | Burnout | |

| Custody-on-Officer Assaults | Verbal Violence Minor Physical Violence Serious Physical Violence Relationships at work | |||

| Workplace Factors | Role Clarity Role Overload Role in the organization | |||

| Job Satisfaction Survey | Perceptions toward Job (8 Items) Career development | |||

| Clements, & Kinman, (2021) [29] | 1792 Prison, Correction& Secure Psychiatric Workers | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Abbreviated Version]—3 items | Emotional Exhaustion | |

| Stress Disclosure—1-item | Ability to discuss stress-related problems with management Relationships at work | |||

| Aggression Measure | Verbal Abuse/Threats Physical Assaults Sexual Harassment/Assault Relationships at work | |||

| Organizational Justice Measure—14-items | Workload, Responsibilities, Reward Fairness Supervisors Behavior & Management Organizational structure & climate | |||

| Health & Safety Executive Management Standards Indicator Tool—8-items | Workload (overload) Working hours Time pressure Incompatible demands Intrinsic to the job | |||

| Gallavan & Newman, (2013) [30] | 101 Correction Mental Health Providers | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey—22-items | Burnout | |

| Professional Quality of Life Survey—Version 5—30-items | Compassion Satisfaction Secondary Traumatic Stress Career development relationships at work | |||

| Life Orientation Test—Revised | Dispositional Optimism Individual | |||

| Work-Family Conflict Scale & Family Work Conflict Scale]—10-items | Interrole Conflict Familial Interference with Work Duties Extra-organizational | |||

| Attitude Toward Prisoners Scale | Attitudes Towards Prisoners Individual | |||

| Hu, Wang, Liu, Wu, Yang, Wang, & Wang (2015) [31] | 1769 Correctional Officers | Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey—Chinese Version 16-items | Burnout | |

| Work Conditions—4-items | Work Hours Work Shift Salary Intrinsic to the job | |||

| Work Stress Scale for Correctional Officers 7-items | Perceived Threat Intrinsic to the job | |||

| Effort Reward Imbalance 17-items | Job Effort Job Reward Over Commitment Organizational climate/structure |

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Yes | |

| ☐ | Diagnosis (one of the following must be checked off a ‘yes’) |

| ☐ Burnout (shows symptoms as determined by a valid psychometric measurement and/or biomedical measure) | |

| ☐ Stress (shows symptoms as determined by a valid psychometric measurement and/or biomedical measure) | |

| ☐ | Correlation (one of the following must be checked off a ‘yes’) |

| ☐ Must measure correlates of stress and/or burnout | |

| ☐ Correlates must be organizationally based | |

| ☐ | Outcome (must be checked off as a yes) |

| ☐ Description of the how the stressor is correlated to job stress or burnout | |

| ☐ | Design (one must be checked off as ‘yes’) |

| □ Experimental | |

| □ Quasi-experimental | |

| □ Non-experimental | |

| ☐ | Data analysis appropriate for the research questions (were the results directly linked to the aim of the study) |

| □ Were the authors interpretations clear | |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Yes | |

| ☐ | Sample Population (any of the following are grounds for exclusion) |

| ☐ A group that does not consist of front-line inpatient or outpatient professionals working in a psychiatric or forensic facility | |

| No Outcomes (the following are grounds for exclusion) | |

| ☐ | ☐ Does not describe treatment outcomes including mental health, burnout, and/or stress levels |

| ☐ No outcomes about the sample population | |

| Type of Article (any of the following are grounds for exclusion) | |

| ☐ | ☐ non-peer-reviewed article |

| ☐ Book review | |

| ☐ Editorial | |

| ☐ Dissertation | |

| Quality Assessment Appraisal | |

|---|---|

| Quality of Study | Studies Evaluated |

| Excellent | Kaplan et al. (2020); Marconi et al. (2019); Márquez et al. (2021); Norman et al (2020); Wampole & Bressi (2020); [17,18,19,20,21] |

| Good | Bagaric & Markanovic (2021); Hill et al. (2010); Rollins et al. (2016) [16,22,24] |

| Poor | White et al. (2015); Eriksson et al. (2018); Suyi et al. (2017) [43,44,45] |

| References | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hill et al. (2010) [16] | 19 staff on alcohol dependence ward | 2-day training | |

| Day 1—“Managing stress at the individual, team and organizational level” | Feelings of personal accomplishment increased | ||

| Day 2—“Understanding the causes and consequences of aggression” | Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization decreased slightly | ||

| Márquez et al. (2021) [20] | 20 National police officers in Spain | 7-week mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention | Significant differences in mindfulness, compassion satisfaction, and perceived stress levels |

| Norman et al. (2020) [17] | 166 prison employees across 13 prison wards in Sweden | Group training on everyday conversations | Significantly lowering cynicism |

| Kaplan et al. (2020) [19] | 31 law enforcement officers | 8-week mindfulness-based resilience training | Increased mindfulness predicted decreased alcohol use |

| Increased self-compassion predicted reduced burnout | |||

| Wampole, & Bressi (2020) [21] | 8 nurses at psychiatric inpatient unit | 12 weekly hour-long psychoeducational sessions based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy’s module on Core Mindfulness | Mindfulness helped participants develop a skill to decrease stress |

| Marconi et al. (2019) [18] | 34 psychiatric health professionals employed at G. Salvini Hospital, Garbagnate Milanese | 18-week intervention focused on training mindfulness meditation | Decrease in depression, worry, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion |

| Rollins et al. (2016) [24] | 145 employees across 5 organizations providing behavioral health care services | Burnout Reduction: Enhanced Awareness, Tools, Handouts, and Education (BREATHE) | Small, statistically significant improvement in burnout |

| Bagaric, & Markanovic (2021) [22] | 55 participants, employees of the Ministry of Justice prison system, from four penal institutions: the prisons in Glina, Lepoglava, Gospid, and Zagreb | 8 two- hour group workshops | Significantly decreased symptoms 2. Greater experience of subjective well-being and better everyday functioning |

| Reduced feelings of stress and burnout |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forman-Dolan, J.; Caggiano, C.; Anillo, I.; Kennedy, T.D. Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169954

Forman-Dolan J, Caggiano C, Anillo I, Kennedy TD. Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169954

Chicago/Turabian StyleForman-Dolan, Justice, Claire Caggiano, Isabelle Anillo, and Tom Dean Kennedy. 2022. "Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169954

APA StyleForman-Dolan, J., Caggiano, C., Anillo, I., & Kennedy, T. D. (2022). Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169954