The Wellbeing of Chinese Migrating Grandparents Supporting Adult Children: Negotiating in Home-Making Practices

Abstract

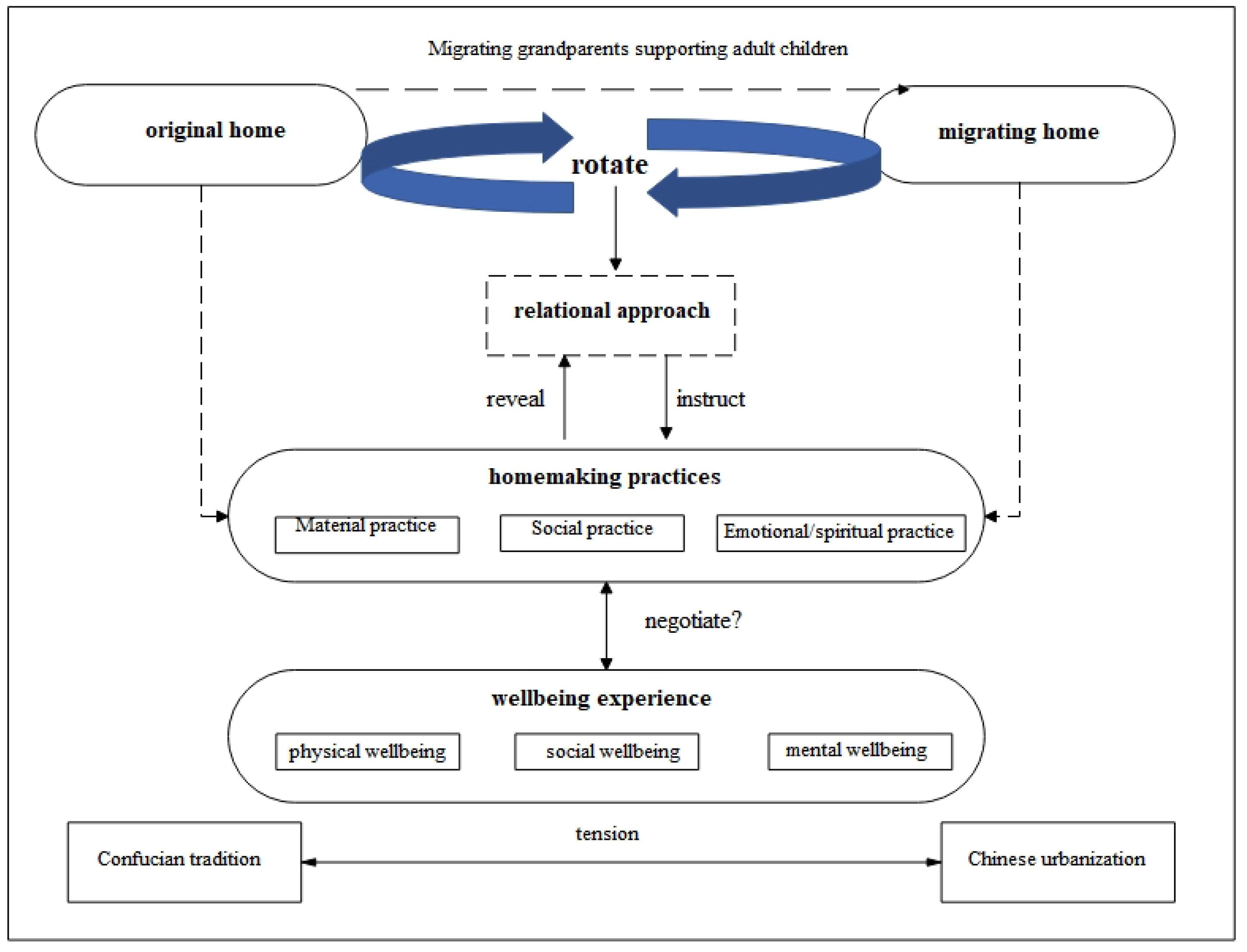

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Wellbeing of Elderly and Home: A Relational Approach

2.2. Home-Making and the Older Migrants

2.3. Migrating Grandparents in the Chinese Context

3. Method

3.1. The Case City

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Material Practices: Sacrifices and Gains

“I should leave some space for the children. It’s not easy for them (after working) a whole day. Let them three watch TV and do something of their own in the living room…I just browsed the mobile phone in my bedroom. Now the mobile phone is very convenient.”(A05)

“After breakfast, we send our grandson to school. Then we have housework to do. We wash clothes and clean the house. It takes almost the whole morning. Then we read the news on the phone. Sometimes we go out for a walk. After lunch in the afternoon, we have a rest for an hour. Around 2 o’clock, we go out for a walk. Then we get our grandson back. I accompanied my grandson to study. Sometimes I asked him to write and read. After supper, I took him out to play in the small park. He played with other children. At 7 o’clock, we would come back to watch TV. At 9 o’clock, I would wash my face and go to sleep. That’s the end of my day.”(A11)

“I usually pay more attention to my mother’s health. After all, she’s old. I tell her if feeling uncomfortable, speak out and don’t hold on… body comes first.”(B08)

“If the elders get sick, the family will be in disorder.”(B06)

“We basically bear all (the daily expenses). It’s already so hard for them (their parents) to come to help us. Their round-trip fare, we also pay.”(B05)

“I’m not used to the food in Shanghai. The food back home tastes salty and spicy, but the food in Shanghai tastes very sweet.”(A29)

“At the beginning, when I came to Shanghai, I was a little uncomfortable. Three years later, things are getting better. In the beginning, I had diarrhea and didn’t feel well.”(A06)

“The wax gourd here tastes different from ours. There is a smell in it. The lotus root is not glutinous either. But we still get used to using them in soups, duck soup and rib soup, which is a typical way of cooking in our hometown.”(From the first author’s field notes)

“We also have express delivery (in our hometown), but it’s not as fast as here……There are packages to pick up almost every day……You can buy anything you want through your phone… I’ve also bought earth eggs a few times……If they (the kids) don’t like the dish of the day, they can also ask for “Wai Mai (take-out food)” and in half an hour, they will arrive. Very convenient.”(A16)

“In Shanghai, I have opened my eyes and learned a lot of fashionable things. Recently, I gradually learned to sort my garbage. I will probably keep this habit when I return to Xuancheng (my home city) in the future.”(A29)

4.2. Social Practices: Restrictions and Reconstructions

“There are singing and dancing (teams) in the community, but I have no time. Sometimes they (practice) at 8 a.m. or 4 p.m., but I can’t leave. Because there are little kids here, you have to take care of them, right? My wife has to cook. There is no one to pick up my little granddaughter outside, or she must stay at home alone, right? The old ladies are singing and dancing in the community, but I can’t join. No way. If it’s just our old couple here, then it’s possible.”(A09)

“In Shanghai, there are also friends like us looking after grandchildren. We chat together. When we take our babies out to play, we are mostly the same age. Then we get to know each other.”(A06)

“…We have gathered a group of the same people here. For example, many grandmothers and maternal grandmothers in our neighborhood also come to care for their grandsons or granddaughters. They play in this neighborhood. We are similar. Later, we became familiar with each other. We chat like close friends, talk and play. At leisure, we bring kids to play together, play together there, just like new old friends. Then you will feel a little more delighted, a little happier, and life is not so monotonous, not completely staying home. We feel happy to play with some new friends.”(A08)

“We keep the connection on WeChat...Generally, there are many brothers and sisters of our age. All are retired. Then I’m afraid they ask me, ‘When will you come back? ’Once they ask me, my heart seems to be very uncomfortable. I will tell them that don’t ask me when I will come back. I will tell you when I want to come back. I say that when you ask me, my heart will crack.”(A14)

4.3. Emotional Practices: Attachments and Entanglements

“…After arriving here, I stay at home. Say a bad word, I’m a nanny. I’m here to serve them, such as babysitting and doing housework…I want to relieve their burden, not employ a nanny.”(A08)

“Anyway, it’s necessary to do things conscientiously and contribute to our children. (We have) no other requirements. We have shallow requirements for ourselves. We just contribute to others. It’s all true. It is what our generation is. Bearing hardship without complaint, we are just nannies.”(A10)

“……The elderly in China always regards children as the center of our lives. After reaching old age, children are usually not around, and life will feel lost. So, although tired, bringing up the grandchildren feels very fulfilling and meaningful.”(C05)

“They are extremely good with the grandchildren, even closer than their daughters. These days they come back to their hometown and make phone calls (with the grandchildren) every day.”(B08)

“At first, I was not very satisfied (with life in Shanghai), but now I slowly get used to it, (though) there will always be something unsatisfied. after staying here long, I want to go back. But if I go back and stay at home, I will miss them and want to come back again. Later, my son said to me, ‘You just have a rest in your hometown, and have a reunion when coming to Shanghai.”(A21)

“We just pretend to be travelling each time we switch the place… to feel the different lives in both the big and small cities is also a wonderful thing”.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Research Summary

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nordbakke, S.; Schwanen, T. Well-being and mobility: A theoretical framework and literature review focusing on older people. Mobilities 2014, 9, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Curtis, S.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Macintyre, S. Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conradson, D. Landscape, care and the relational self: Therapeutic encounters in rural England. Health Place 2005, 11, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, L.; Xu, H.; Kwan, M.-P. Seasonal mobility and well-being of older people: The case of ‘Snowbirds’ to Sanya, China. Health Place 2018, 54, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Hardill, I. Retirement migration, the ‘other’story: Caring for frail elderly British citizens in Spain. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panelli, R.; Tipa, G. Placing Well-Being: A Maori Case Study of Cultural and Environmental Specificity. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Atkinson, S. Geographies of wellbeing: An introduction. Geogr. J. 2015, 181, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.Y. Individual educational attainment, neighborhood-socioeconomic contexts, and self-rated health of middle-aged and elderly Chinese: Exploring the mediating role of social engagement. Health Place 2017, 44, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, S. The impact of children leaving home on the parents’ wellbeing: A comparative analysis of France and Italy. Genus 2006, 62, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Corley, J.; Okely, J.A.; Taylor, A.M.; Page, D.; Russ, T.C. Home garden use during COVID-19: Associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. J Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaney, R.; Reid, L.; Currie, M. The contribution of healthcare smart homes to older peoples’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.; Kealy, A.; Loane, J.; Walsh, L.; O’Mullane, B.; Flynn, C.; Macfarlane, A.; Bortz, B.; Knapp, R.B.; Bond, R. An integrated home-based self-management system to support the wellbeing of older adults. J. Amb. Intel. Smart Environ. 2014, 6, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Easthope, H. A place called home. Hous. Theory Soc. 2004, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. In The New Social Theory Reader, 2nd ed.; Seidman, S., Alexander, J.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R. Editor’s Choice: The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Luo, H.; Hui, T. Moving for a good life: Tourism mobility and subjective well-being of Chinese retirement migrants. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Hannam, K.; Xu, H.-G. Reconceptualising home in seasonal Chinese tourism mobilities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.S.; Sin, H.L. Going on holiday only to come home: Making happy families in Singapore. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, P.-C.; Hank, K. Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China and Korea: Findings from CHARLS and KLoSA. J. Gerontol. B-Psychol. 2014, 69, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ducu, V.; Nedelcu, M.; Telegdi-Csetri, A. Zero Generation Grandparents Caring for Their Grandchildren in Switzerland. The Diversity of Transnational Care Arrangements among EU and Non-EU Migrant Families. In Childhood and Parenting in Transnational Settings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Xia, Y. Grandparenting in Chinese immigrant families. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2011, 47, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.-P.; Zhang, L.-L. Familyization and Consumption Expenditure of Floating Population in Beijing. J. Admin. Inst. 2020, 22, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Boccagni, P. What’s in a (migrant) house? Changing domestic spaces, the negotiation of belonging and home-making in Ecuadorian migration. Hous. Theory Soc. 2014, 31, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M. Mobile locations: Construction of home in a group of mobile transnational professionals. Glob. Netw. 2007, 7, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K. Migrant masculinities and domestic space: British home-making practices in Dubai. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuret, S.; Atkinson, S. Wellbeing, health and geography: A critical review and research agenda. N. Z. Geogr. 2007, 63, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Allen, R.E.; Palmer, A.J.; Hayman, K.J.; Keeling, S.; Kerse, N. Older people and their social spaces: A study of well-being and attachment to place in Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Tang, S.; Chuai, X. The impact of neighbourhood environments on quality of life of elderly people: Evidence from Nanjing, China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, F.; Schwanen, T. ‘I like to go out to be energised by different people’: An exploratory analysis of mobility and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, C.; Jones, K.; Moon, G. Context, composition and heterogeneity: Using multilevel models in health research. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R. Local environments and older people’s health: Dimensions from a comparative qualitative study in Scotland. Health Place 2008, 14, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutchin, M.P. The process of mediated aging-in-place: A theoretically and empirically based model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsfall, D.; Leonard, R.; Rosenberg, J.P.; Noonan, K. Home as a place of caring and wellbeing? A qualitative study of informal carers and caring networks lived experiences of providing in-home end-of-life care. Health Place 2017, 46, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.; Wiles, J.; Kearns, R.; Coleman, T. Precariously placed: Home, housing and wellbeing for older renters. Health Place 2019, 58, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D.B. For Space; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Di, X.; Dai, X. Family support, multidimensional health, and living satisfaction among the elderly: A case from Shaanxi province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Holten, K.; Ammann, E.S. Negotiating the potato: The challenge of dealing with multiple diversities in elder care. In Transnational Aging; Horn, V., Schweppe, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 212–228. [Google Scholar]

- Forssell, E.; Torres, S. Social work, older people and migration: An overview of the situation in Sweden. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2012, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, S. Traveling Institutions as Transnational Aging: The Old-Age Home in Idea and Practice in India. In Transnational Aging; Horn, V., Schweppe, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 190–211. [Google Scholar]

- Fozdar, F.; Hartley, L. Housing and the creation of home for refugees in Western Australia. Hous. Theory Soc. 2014, 31, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofsen, M. Performing “home” in the sharing economies of tourism: The Airbnb experience in Sofia, Bulgaria. Fennia 2018, 196, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, A.; Dowling, R. Setting up home: An introduction. In Home, 2nd ed.; Blunt, A., Dowling, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph, D.; Staeheli, L.A. Home and migration: Mobilities, belongings and identities. Geogr. Compass 2011, 5, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kong, L. Globalisation and Singaporean transmigration: Re-imagining and negotiating national identity. Polit. Geogr. 1999, 18, 563–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeoh, B.S.; Huang, S. Transnational domestic workers and the negotiation of mobility and work practices in Singapore’s home-spaces. Mobilities 2010, 5, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, N. Landscapes of Privilege: The Politics of the Aesthetic in an American Suburb; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.; Li, P.; Zhong, H. Progress and Enlightenment of Geographical Research on “Home” Abroad. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 809–817. [Google Scholar]

- Zick, C.D. Families and Time: Keeping Pace in a Hurried Culture. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 1997, 553, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times; Metropolitan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-G.; Wu, H.-L. A study on the urban residence intention of the elderly who moved with them under the background of the two-child policy. Acad. Res. 2016, 29, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, S.-H. Analysis of the mental health status and influencing factors of the elderly who moved with them in Shenzhen, China. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2015, 227, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.-X.; Xin, Z.-Q. The relationship between intergroup contact and well-being of migrant elderly and local elderly. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhan, H.J. The making of a home in a foreign land: Understanding the process of home-making among immigrant Chinese elders in the US. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 1539–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G. Place and space in home-making processes and the construction of identities in transnational migration. Trans. Soc. Rev. 2016, 6, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M. Transnational Professionals and Their Cosmopolitan Universes; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, N.; Martin, D. “I’m a foreigner there”: Landscape, wellbeing and the geographies of home. Health Place 2020, 62, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, I.; Dossa, P. Place, health and home: Gender and migration in the constitution of healthy space. Health Place 2007, 13, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Näre, L. Introduction: Transnational migration and home in older age. In Transnational Migration and Home in Older Age; Walsh, K., Näre, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, P.K. Concepts of Chinese folk happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.-T. Rural China; The People’s Literature Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chyi, H.; Mao, S. The determinants of happiness of China’s elderly population. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.-Q.; Huang, J.-Y. Reconstruction of family culture in immigrant families. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2018, 234, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Wang, C.; Cao, X.; Zhu, H.; Luo, L. Unmet Healthcare Needs and Their Determining Factors among Unwell Migrants: A Comparative Study in Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Xu, H.-G. The local attachment of the “home” of seasonal retired migrants: Taking Sanya as an example. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 34, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Decrop, A. Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Management 1999, 20, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P. Culinary tourism as living history: Staging, tourist performance and perceptions of authenticity in a Thai cooking school. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampioni, M.; Moșoi, A.A.; Rossi, L.; Moraru, S.-A.; Rosenberg, D.; Stara, V. A Qualitative Study toward Technologies for Active and Healthy Aging: A Thematic Analysis of Perspectives among Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary End Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Gomi, T.; Katsube, T. Challenges and solutions in the continuity of home care for rural older people: A thematic analysis. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2020, 39, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, A. Transnational homemaking practices: Identity, belonging and informal learning. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 2013, 21, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.-A. Homemaking in New Zealand: Thinking through the mutually constitutive relationship between domestic material objects, heterosexuality and home. Gender Place Cult. 2013, 20, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M. Health and Well-Being Across the Life Course; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Swanborn, P.G. A common base for quality control criteria in quantitative and qualitative research. Qual. Quant. 1996, 30, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S. Chinese Contemporary Family, “Division” and “Unity” of Household and Family. Soc. Sci. China 2016, 37, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. Chinese Families Upside Down: Intergenerational Dynamics and Neo-Familism in the Early 21st Century; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Approaches | Understanding of Place | Understanding of Wellbeing | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional approach |

|

| [2,4,8,30,31] |

| Relational approach |

|

| [2,4,5,7,27,28,29,32] |

| No. | Gender | Age | Hometown | Moving Time | Back to Hometown Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent Information in Stage 1 | |||||

| A01 | Female | 60 | Hubei | 10 years | Returns in case of problems |

| A02 | Female | 59 | Huzhou, Zhejiang | 4 years | Returns for festivals |

| A03 | Female | 70 | Jiangsu | 4 years | Returns in case of problems |

| A04 | Female | 56 | Dalian, Liaoning | Unknown | Returns in case of problems |

| A05 | Female | 60 | Xi’an, Shaanxi | 6 years | Problems and festivals |

| A06 | Female | 60 | Jiangxi | 5.5 years | Returns for festivals |

| A07 | Female | 55 | Shandong | 3 years | Returns on National Day, Spring Festival, Father’s birthday |

| A08 | Female | 68 | Zhenjiang, Jiangsu | 13 years | Returns for festivals |

| A09 | Female | 70 | Nanchang, Jiangxi | 8 years | Returns in case of problems |

| A10 | Female | 69 | Jingjiang, Jiangsu | 21 years | Once to twice a year |

| A11 | Male | 72 | Anhui | 5.5 years | 1–2 months each year |

| A12 | Female | 66 | Lianyungang, Jiangsu | 5.5 years | Once a year |

| A13 | Female | 66 | Shangrao, Jiangxi | 15 years | Once a year |

| A14 | Male | 59 | Fuzhou, Fujian | 5 years | Returns in winter and summer vacation |

| A15 | Female | 57 | Songyuan, Jilin | 4 years | 4–8 months each year |

| A16 | Female | 73 | Yangzhou, Jiangsu | 13 years | Twice a year (Spring Festival, National Day) |

| A17 | Male | 68 | Chizhou, Anhui | 21 years | About 3 times a year (busy farming season) |

| A18 | Female | 69 | Zhenjiang, Jiangsu | 3 years | About 6 times a year |

| A19 | Female | 65 | Chengdu, Sichuan | 7 years | Twice a year |

| A20 | Female | 71 | Dangshan, Anhui | 10 years | About 3 times a year (busy farming season) |

| A21 | Female | 63 | Nantong, Jiangsu | 5 years | About 3 times a year, rotate with A22 |

| A22 | Male | 63 | Hefei, Anhui | 5 years | About 3 times a year, rotate with A21 |

| A23 | Female | 58 | Nantong, Jiangsu | 9 years | About three times a year (busy farming season) |

| A24 | Male | 75 | Yichun, Jiangxi | 12 years | 3 times a year (Qing Ming and Spring Festival, National Day) |

| A25 | Female | 58 | Huaian, Jiangsu | 3 years | Twice a year |

| A26 | Female | 51 | Hefei, Anhui | 3 years | About 10 times a year (personal affairs) |

| A27 | Female | 63 | Suzhou, Jiangsu | 2 years | 4 times a year (personal affairs and rest) |

| A28 | Female | 53 | Jingdezhen, Jiangxi | 3 years | Twice a year |

| A29 | Male | 68 | Xuancheng, Anhui | 3 years | About 7 times a year |

| A30 | Female | 69 | Xuzhou, Jiangsu | 2 years | 3 times a year |

| Respondent Information in Stage 2 | |||||

| C01 | Female | 56 | Wuhan, Hubei | 6 years | 2–3 times a year |

| C02 | Male | 62 | Wuhan, Hubei | 6 years | 2–3 times a year |

| C03 | Female | 57 | Huangshan, Anhui | about 4 years | 2–3 times a year |

| C04 | Male | 64 | Huangshan, Anhui | about 4 years | 2–3 times a year |

| C05 | Female | 62 | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | Several years (not specific) | About 3 times a year |

| No. | Gender | Work in Shanghai | Family Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| B01 | Female | Company treasurer | Daughter-in-law of A15 |

| B02 | Female | Florist | Daughter-in-law of A16 |

| B03 | Female | Civil servant | Daughter of A18 |

| B04 | Male | Unknown | Son of A20 |

| B05 | Female | Civil servant | Daughter of A21, daughter-in-law of A22 |

| B06 | Female | Civil servant | Daughter of A23 |

| B07 | Male | Civil servant | Son of A25 |

| B08 | Female | Graduate student | Daughter of A26 |

| B09 | Female | Civil servant | Daughter of A27 |

| Concept | Categories | Explanations | Exemplary Labels | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home-making practice | Material home-making practices | Material practices to maintain physiological and psychological security and stability | Housework, food and expenditure arrangement, usage of the material space, facilities, goods in relation to two homes | [17,20,25,42,47,64,69,70] |

| Social home-making practices | Social practices building and maintaining familiar social network | Socialization with familiar friends and relatives, making social bonds at multi-scales | ||

| Emotional/spiritual home-making practices | Practices to generate emotional or spiritual attachments | Communicate and build emotional bonds with the family members, communities, migrating and homeland places | ||

| Wellbeing experience | Physical wellbeing | The physiological/physical health of human body | Physical health, physical strength; easy body | [4,29,71,72] |

| Social wellbeing | A good state of social contacts and supports | Fulfillment of social needs, feel socially connected with friends and relatives | ||

| Mental wellbeing | Peoples’ positive feelings, emotions and spiritual attachments | Spiritual fulfillment, mental happiness and enjoyment; satisfaction with life in the psychological sense |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, D.; Xu, H.; Yao, Y. The Wellbeing of Chinese Migrating Grandparents Supporting Adult Children: Negotiating in Home-Making Practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169903

Zhu D, Xu H, Yao Y. The Wellbeing of Chinese Migrating Grandparents Supporting Adult Children: Negotiating in Home-Making Practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169903

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Dan, Haichao Xu, and Yuan Yao. 2022. "The Wellbeing of Chinese Migrating Grandparents Supporting Adult Children: Negotiating in Home-Making Practices" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169903

APA StyleZhu, D., Xu, H., & Yao, Y. (2022). The Wellbeing of Chinese Migrating Grandparents Supporting Adult Children: Negotiating in Home-Making Practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169903