The Double Mediating Effect of Family Support and Family Relationship Satisfaction on Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life among Korean Baby Boomers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Characteristics of Participants in This Study

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Self-Compassion

2.2.2. Family Support

2.2.3. Family Relationship Satisfaction

2.2.4. Meaning in Life

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

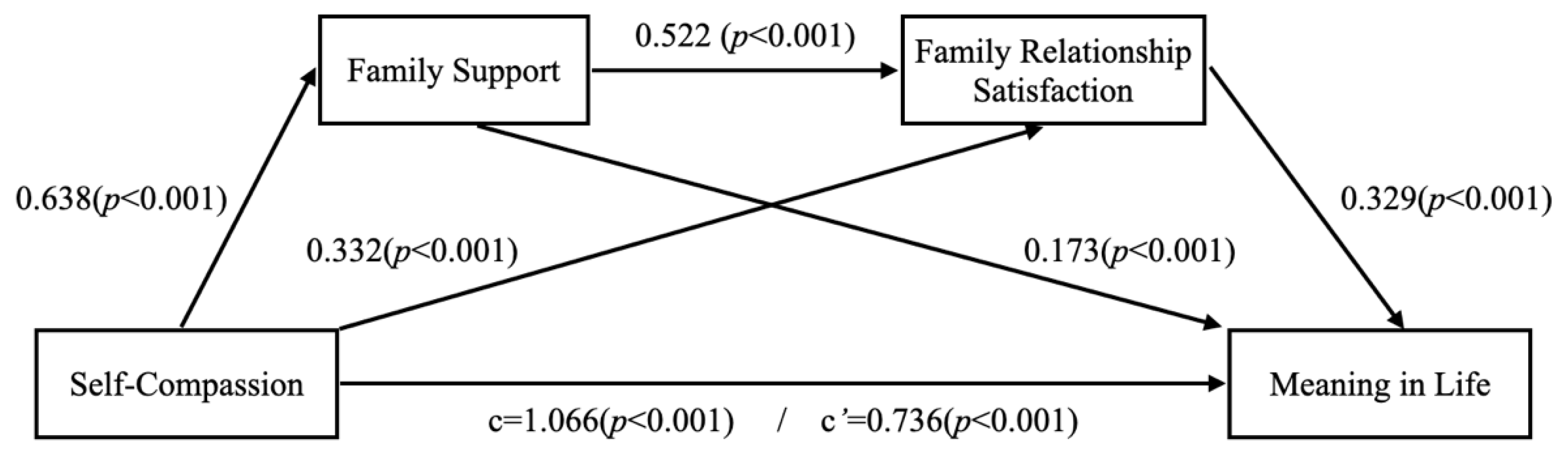

3.2. Verification of the Double Mediation Model for the Meaning in Life of Baby Boomers

4. Discussion

4.1. Results and Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Direction of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korean Statistical Information Service. Preliminary Results of Birth and Death Statistics in 2012; Korean Statistical Information Service: Daegu, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H. A Study on the Difference between the Factors Affecting Happiness between the Baby Boom Generation and the Elderly Generation. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.H. A Study on Digital Divide Influence Factors of the Elderly: Comparison between Baby Boomer and Elderly. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2020, 20, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.M.; Nam, Y.M. A Study on Characteristics of Baby Boomers: Focused on the Chungbuk Area. Soc. Econ. Policy Stud. 2018, 8, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Analysis of Perception Pattern about Social Participation of Baby Boomer Generation. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Stud. 2018, 49, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Tak, J.K.; Kim, H.S.; Nam, D.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Kwon, N.R.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, I.J. Development and Validation of the Work Meaning Inventory. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 28, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.K.; Song, I.J. A Convergence Study on the Effects of Stress on Suicidal Ideation in the Elderly’s-Mediating Effects of Depression-. J. Korea Converg. Soci. 2020, 11, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Statistical Information Service. Causes of Death Statistics in 2010; Korean Statistical Information Service: Daegu, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Welfare. White Book on Suicide Prevention; Ministry of Health & Welfare: Seoul, Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.G. The Sense of Loneliness as a Moderator for Relationship between Financial Loss and Suicidal Ideation in Older Adults Living Alone. Korean J. Gerontol. Soc. Welf. 2014, 63, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, Y. Suicide in later life: A review and recommendation for prevention. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J. Impact of Depression and Family Relationship on Problem Drinking among Older Adults. J. Digit. Converg. 2016, 14, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumeister, R.F. Meaning of Life; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.H.; Kim, D.B.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, Y.G.; Kim, A.S. A Study on Improvement of the Quality of Life for the Aged. J. Korea Gerontol. Soci. 1998, 18, 150–169. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.S. A Study on the Types of Life Satisfaction and Related Variables of the Elderly. Soc. Welf. Policy Pract. 2020, 6, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, J.B. Guideposts to Meaning: Discovering What Really Matters; New Harbinger Publications Inc.: Oakland, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.J. The Development of Logotherapeutic Program for Elders to Enhance Ego Integrity. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul University of Buddhism, Seoul, Korea, 2015. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.J.; Hyun, M.H. The Effects of Nostalgia on Meaning in Life, Positive Affect and Gratitude of College Students in Existential Vacuum State. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Gutierrez, I.A. Global and situational meaning in the context of trauma: Relations with psychological well-being. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2013, 26, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, K.N.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Reeve, C.L. Posttraumatic growth, meaning in life, and life satisfaction in response to trauma. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2012, 4, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, H.; Shin, H.C. The Influence of Stress on Suicide Ideation: Meaning in Life as Mediator or Moderator. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2009, 21, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V.E. The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy; New American Library: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, A.M.; Joseph, S.; Maltby, J. Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the Big Five facets. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S.; Park, J.A. Research Trends and Implications in Meaning in life. Ewha J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 29, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamonti, P.; Lombardi, S.; Duberstein, P.R.; King, D.A.; Van Orden, K.A. Spirituality attenuates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life. Aging Ment Health. 2016, 20, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chae, S.H.; Kim, J.S. A Meta-Analysis on Variables Related to the Meaning in Life. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2020, 32, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, Y.; Song, K.Y.; Park, O.J.; Ko, S.H.; Park, M.H. Introduction to Gerontological Nursing; Hyunmoon: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.G. Study on a moderating effect of psycho-social characteristics in the relationship between depression and suicidal ideation among community elderly. J. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2008, 28, 969–989. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, B.; Szepsenwol, O.; Zilcha-Mano, S.; Haim, N.; Zamir, O.; Levi-Yeshuvi, S.; Levit-Binnun, N. A wait-list randomized controlled trial of loving-kindness meditation programme for self-criticism. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 22, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanto, N.; Zuroff, D.C.; Kopala-Sibley, D.C.; Kelly, A.C.; Matos, M.; Gilbert, P.; Koestner, R. Ability to receive compassion from others buffers the depressogenic effect of self-criticism: A cross-cultural multi-study analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 98, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irons, C. The Compassionate Mind Approach to Difficult Emotions: Using Compassion Focused Therapy; Robinson: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vliegen, N.; Luyten, P. Dependency and self-criticism in post-partum depression and anxiety: A case control study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2009, 16, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.J.; Rector, N.A.; Bagby, R.M.; Swinson, R.P.; Levitt, A.J.; Joffe, R.T. Is self-criticism unique for depression? A comparison with social phobia. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 57, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, I.; Bodner, E.; Ben-Zion, I.Z. Self-esteem, dependency, self-efficacy and self- criticism in social anxiety disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 58, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.J.; MacPherson, P.S.; Enns, M.W.; McWilliams, L.A. Neuroticism and self-criticism associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a nationally representative sample. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, L.H.; Weierich, M.R.; Hooley, J.M.; Deliberto, T.L.; Nock, M.K. Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.M.; Song, M.K. Self-Criticism and Depression in University Students: The Mediating Effects of Internal Entrapment and Rumination. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.C.; Park, E.J.; Kim, E.H. The Mediating Effects of Internalized Shame and Depression in the relationship between Self-Criticism and Suicidal Ideation. Korea Soc. Wellness 2016, 11, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Noyce, R. Personality and cognitive processes: Self-criticism and different types of rumination as predictors of suicidal ideation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neff, K.D. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identit. 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.R. The Effects of Self-Compassion, Psychological Acceptance, Mindfulness on Forgiveness. Master’s Thesis, Konyang University, Daejeon, Korea, 2010. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.R. The Effects of Self-Compassion, Life Stress, and Decentering on Psychological Health: A Mediated Moderation Model. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 30, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kang, L.Y. Interpersonal Competence: Mediating Effect of Emotion Control Strategy. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 11, 2035–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Hong, H.Y. The Relationship Between Internalized Shame and Interpersonal Relation Problems of College Students: The Mediating Effects of Self-Compassion and Mentalization. Korea J. Couns. 2021, 22, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.Y.; Yang, H.C. Self-Compassion and Marital Quality: Dyadic Perspective Taking and Dysfunctional Communication Behavior as Mediators. Fam. Fam. Ther. 2018, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Procter, S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockcliff, H.; Gilbert, P.; McEwan, K.; Lightman, S.; Glover, D. A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol responses to compassion-focused imagery. J. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2008, 5, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A.B.; Leary, M.R. Self-compassionate Responses to Aging. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.P.; Nam, S.I. The Mediation Effect of Self-compassion on the Relationship between Loneliness and Successful Aging of Elderly Koreans. J. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2015, 35, 671–687. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.D.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, K.S.; Park, S.J. Structural Relationship of Family Cohesion, Stress, Depression and Problem Drinking for the Elderly. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandini, R. Family relations as social capital. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2014, 45, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rözer, J.; Mollenhorst, G.; Poortman, A.R. Family and friends: Which types of personal relationships go together in a network? Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olsson, C.A.; Bond, L.; Burns, J.M.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A.; Sawyer, S.M. Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Kim, N.Y. Study on the Effect of Social Support on Depression of the Old. Korean J. Clin. Soc. Work 2007, 4, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.G. Factors Influencing Health Promoting Behavior of the Elderly: Perceived Family Support and Life Satisfaction. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2002, 13, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.K. The Influence of Self-Compassion on Other-Compassion: Mediating Effects of Positive Emotions and Social Connectedness. Korean J. Rehabil. Psychol. 2018, 25, 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Pyen, S.W.; Lee, D.G. The Influence of Gratitude Attitude and Gratitude Expression on Romantic Relationship Satisfaction: The Mediating Effects of Self-Compassion and Perceived Social Support. Korean J. Rehabil. Psychol. 2020, 27, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.W.; Joeng, J.R. The Mediating Effects of Emotional Support and Self-compassion on the Relationships between Loneliness Caused by Interpersonal Stress Events and Post-adversity Growth. Korea J. Couns. 2018, 19, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.J.; Jung, J.H. The relationship between unstable attachment for mother & father and post-traumatic growth: The double-mediating effect of perceived social support and self-compassion. Stud. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 22, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, W.C.; Uchino, B.N.; Smith, T.W.; Light, K.C.; Butner, J. It’s complicated: Marital ambivalence on ambulatory blood pressure and daily interpersonal functioning. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, N.J.; Backlund, E.; Sorlie, P.D.; Loveless, C.A. Marital status and mortality. Ann. Epidemiol. 2000, 10, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, T.F.; Slatcher, R.B.; Trombello, J.M.; McGinn, M.M. Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 140–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holttum, S. Inclusion of family and parenthood in mental health recovery. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2018, 22, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.H.; Riggs, S.A.; Ruggero, C. Coping, family social support, and psychological symptoms among student veterans. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coty, M.B.; Wallston, K.A. Problematic social support, family functioning, and subjective well-being in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Women Health 2010, 50, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekka, D.; Pachi, A.; Tselebis, A.; Zafeiropoulos, G.; Bratis, D.; Evmolpidi, A.; Tzanakis, N. Pain and anxiety versus sense of family support in lung cancer patients. Pain Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 312941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Song, E.H. The impact of meaning of life, family support and institutional environment on successful aging among the institutionalized elderly: Focused on gender. Korean J. Gerontol. Soc. Welf. 2012, 58, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.D. A Comparative Study on the Successful Aging for Korean Elderly Women and Elderly Men. J. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2007, 27, 829–845. [Google Scholar]

- Reker, G.R. Prospective predictors of successful aging in community-residing and institutionalized Canadian elderly. Aging Int. 2002, 27, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B. A Study on Purpose in Life, Family Support, Death Anxiety and Well-dying of the Elderly. J. Learn.-Cent. Curric. Instr. 2019, 19, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W. A study on the Effects of the Family Support and Self-Esteem on Elderly s Life Satisfaction. J. Couns. Psychol. Educ. Welf. 2015, 2, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.R. A study on Family values, Preparation for Old Age and Life Satisfaction for Baby-Boom Generation. Master’s Thesis, Daegu University, Daegu, Korea, 2011. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Y.S.; Jo, S.A.; An, J.S.; Jeong, Y.J. Effect of Family Relations as a Source of Meaning of Life and Self-transcendence Value on Successful Aging In Korean Elders. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 25, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, Y.W.; Lee, T.S. A Study on the Effects of Care-giving Stress on Family Relationship Satisfaction. Korean J. Fam. Welf. 2010, 15, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ebersole, P.; DePaola, S. Meaning in life categories of later life couples. J. Psychol. 1987, 121, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J. A Study of the Quality of Life in Old People. Ph.D. Thesis, Ewha University, Seoul, Korea, 2001. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D.R. Social and Personality Development; Cengage Learning: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B.A.; Krause, N.; Bennett, J. Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. J. Gerontol. 2007, 62, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Travis, L.A.; Lyness, J.M.; Shields, G.G.; King, D.; Cox, C. Social support, depression, and functional disability in older adult primary care patients. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of Parenting Stress, Sleep Quality, Self-Compassion and Family Relationship on Mothers’ Postpartum Depression. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2002, 29, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J. The Influence of caregiving stress on depression in grandmothers raising infant grandchildren in double-earner households: Focus on the mediating effects of spousal emotional support, the grandmother-adult parent relationship, and family support. Korean J. Fam. Welf. 2012, 17, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J. A Study on the Relationships between Life Quality of Elderly with Dementia and Family Relationship. J. Fam. Relat. 2011, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson, G.; Skar, L.; Lexell, J. Women’s perception of changes in the social network after spinal cord injury. Disabil. Rehabilit. 2005, 27, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.; Glass, T.A.; Palmer, J.B.; Loo, S.; Wegener, S.T. Crisis intervention with individuals and their families following stroke: A model for psychosocial service during inpatient rehabilitation. Rehabilit. Psychol. 2004, 49, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, S.K.; Teasell, R.W.; Foley, N.C.; Speechley, M.R. Rehabilitation of aphasia: More is better. Top Stroke Rehabilit. 2003, 10, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Sung, H.Y. The Moderating Effect of Family Relationship on Depression in the Elderly. J. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2009, 29, 717–728. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identit. 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.E.; Yi, G.D.; Cho, Y.R.; Chai, S.H.; Lee, W.K. The validation study of the Korean version of the Self-Compassion Scale. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S. Experimental Study of The Effects of Reinforcement Education for Rehabilitation on Hemiplegia Patients’ Self-Care Activities. Ph.D. Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, 1984. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, O.K.; Kim, Y.S. Construction and Validity of Family Relations Scale-Brief Form. J. Fam. Relat. 2007, 12, 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F. Meaning in Life Questionnaire: A Measure of Eudaimonic Well-Being. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Won, D.R.; Kwon, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Validation of the Korean Version of Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.C.; Zuroff, D.C.; Foa, C.L.; Gilbert, P. Who benefits from training in self-compassionate self-regulation? A study of smoking reduction. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 727–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.R. The Effect of Self-Compassion on Self-Regulation: The Effectiveness of the Self-Compassion Enhancement Program. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2015. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, E.J.; Youn, J.H. Double Mediation Effect of Self-compassion and Psychological Acceptance in the Relationship Between Interpersonal Problems and Meaning in Life. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 12, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, J.; Bourbonnais, D.; Noreau, L.; Rochette, A.; Bravo, G.; Bourget, A. Participation after stroke compared to normal aging. J. Rehabilit. Med. 2005, 37, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.H.; Yoon, G.J. Effects of Participating Self-Growth Program on Ego-Integrity and Family Relationship Satisfaction of the Elderly Women. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, T.K.; Choi, H.S. A systematic review of the suicide prevention program for the elderly. Korean J. Stress Res. 2019, 27, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, E.J. A study on the effect of the transactional analysis group program for elderly suicide prevention. J. Welf. Couns. Educ. 2013, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.H. A Phenomenological Study on the Meaning of Work of Baby Boomer Generation: Focusing on Re-Employed People after Retirement. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University, Daegu, Korea, 2017. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Chang, S.J.; Lee, J.J.; Moon, K.J. Factors affecting on the Willingness of Re-employment among Baby boomers. Korean J. Gerontol. Soc. Welf. 2015, 67, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.J. An Exploratory Study for the Exploring the Essential Meaning about Work and Retirement in Baby Boomer. Q. J. Labor Policy 2013, 13, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-compassion | - | |||

| 2. Meaning in life | 0.524 ** | - | ||

| 3. Family support | 0.421 ** | 0.503 ** | - | |

| 4. Family relationship satisfaction | 0.372 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.645 ** | - |

| M | 3.371 | 5.027 | 3.903 | 3.768 |

| SD | 0.503 | 1.024 | 0.863 | 0.795 |

| Skewness | −0.060 | −0.670 | −0.822 | −0.656 |

| Kurtosis | 0.375 | 0.777 | 0.242 | 0.548 |

| Path | B | S.E. | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion → Family support | 0.638 | 0.079 | 7.992 *** | 0.481 | 0.795 |

| Self-compassion → Family relationship satisfaction | 0.332 | 0.063 | 5.268 *** | 0.208 | 0.456 |

| Family support → Family relationship satisfaction | 0.522 | 0.036 | 14.207 *** | 0.450 | 0.594 |

| Self-compassion → Meaning in life | 0.736 | 0.089 | 8.225 *** | 0.560 | 0.912 |

| Family support → Meaning in life | 0.173 | 0.061 | 2.803 *** | 0.051 | 0.295 |

| Family relationship satisfaction → Meaning in life | 0.329 | 0.068 | 4.785 *** | 0.194 | 0.464 |

| Path | Effect | S.E. | BC 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion → Family support → Meaning in life | 0.110 | 0.055 | 0.0143~0.2297 |

| Self-compassion → Family relationship satisfaction → Meaning in life | 0.109 | 0.040 | 0.0414~0.1973 |

| Self-compassion → Family support → Family relationship satisfaction → Meaning in life | 0.110 | 0.039 | 0.0490~0.2017 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.330 | 0.061 | 0.2190~0.4589 |

| Direct effect: Self-compassion → Meaning in life | 0.736 | 0.089 | 0.5604~0.9124 |

| Total effect | 1.066 | 0.086 | 0.8957~1.2375 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, Y.-s.; Lee, Y.-s. The Double Mediating Effect of Family Support and Family Relationship Satisfaction on Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life among Korean Baby Boomers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169806

Jeong Y-s, Lee Y-s. The Double Mediating Effect of Family Support and Family Relationship Satisfaction on Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life among Korean Baby Boomers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169806

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Yu-soo, and Young-soon Lee. 2022. "The Double Mediating Effect of Family Support and Family Relationship Satisfaction on Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life among Korean Baby Boomers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169806

APA StyleJeong, Y.-s., & Lee, Y.-s. (2022). The Double Mediating Effect of Family Support and Family Relationship Satisfaction on Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life among Korean Baby Boomers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169806