Abstract

Dog aggression directed towards people is a leading reason for relinquishment and a major public health hazard. In response to the threat of dog aggression and dog bites, breed-specific legislation has been introduced in numerous cities within the United States and countries throughout the world. There is limited evidence, however, to suggest that such laws are effective. This study explored, through an online, anonymous, cross-sectional survey, US residents’ views about the bite risk of common dog breeds, breed-specific legislation, and alternative options for improved public safety. A total of 586 surveys were completed by adult US residents, 48.8% female and 48.6% male. Approximately half of the respondents reported feeling that dog bites are a serious public health issue. Although 70% of respondents were opposed to a breed ban, only 56% felt that banning specific breeds creates an animal welfare issue. Females were less likely to support a ban or agree that specific breed bans improve public safety. When participants were asked to indicate their support of several alternatives to breed-specific legislation, the most frequently endorsed options included public education about animal welfare and animal behavior, and stricter leash laws. Further research pertaining to the most effective public education dissemination methods is warranted.

1. Introduction

A total of 45% of US households included at least one dog in 2020, a dramatic increase from the 38% of households in 2016 [1]. The popularity of dogs is unsurprising given that having a companion dog has been shown to have a positive effect on numerous aspects of guardians’ emotional and physical health [2,3,4,5,6]. Although dogs in the home offer many benefits, they can also involve zoonotic diseases [7], injuries and accidents [8,9,10], and bite risks [11,12,13].

Dog aggression directed towards people is the most common canine behavior problem for which guardians seek help, one of the leading reasons for relinquishment [14,15], and a major public health hazard, especially for young children [16,17,18]. More than 4.5 million people are bitten by dogs each year in the United States, with dog bites ranking as the 13th leading cause of nonfatal emergency department visits [19,20]. Many bites, however, go unreported, meaning the actual prevalence of bites is likely to be much higher than that reflected in official sources. One study by Westgarth [21] found 25% of people report having ever been bitten by a dog, with only a fraction of these bites resulting in a hospital admissions record.

In response to the threat of dog aggression and dog bites, breed-specific legislation (otherwise referred to as breed bans) has been introduced in the United States and numerous countries around the world. This type of legislation focuses on the banning or strict control of specific breeds deemed a danger to the general public. Although numerous dog breeds have been banned or are viewed as dangerous, one of the most commonly banned breeds is the Pit Bull, which actually consists of three separate breeds: American Staffordshire Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and American Pit Bull Terrier. Many states allow county or city breed-specific restrictions and over 700 cities have breed restrictions [22]. However, there is limited evidence to suggest that such laws are effective. In contrast, there is growing evidence to suggest that such laws are ineffective, negatively impact animal welfare, and, in fact, do little to make communities safer [23,24,25,26,27]. There are many reasons why breed specific legislation is ineffective, including the misidentification of dog breeds, an issue that has been reported among members of the general public, animal shelter workers, law enforcement officers, and human health care professionals [28,29,30,31,32,33]. The fact that most people are unable to accurately identify dog breeds significantly impacts the ability to collect accurate breed-specific bite statistics. As a result, media stories, which influence public perception of different breeds, are often inaccurate and misleading [34,35,36,37]. Even when the breed is accurately identified, because behavior is a complex interaction of contextual and environmental factors, breed provides minimal predictive information about behavior [14,38].

A study exploring US veterinarians’ views on breed bans found only a minority feel a ban improves public safety (11%) and most (75%) feel a ban creates an animal welfare issue. Instead, veterinarians’ support alternative community policies including public education about animal behavior and welfare, stricter leash laws, and harsher penalties for dog owners in the event of a dog bite or attack [39]. Yet, despite the prevalence of breed-specific legislation in the United States and throughout the world, and the media’s depiction of ‘dangerous breeds’, little is known about how dog guardians and non-dog guardians in the United States view bite risk for common dog breeds, breed-specific legislation, and alternative options for improved public safety. Therefore, the objective of this quantitative study was to gain insights into how adults in the US view these factors: common dog breeds in terms of aggression, breed-specific legislation, and alternative public safety laws and programs. We hypothesize that participants will rate Pit Bulls as the most aggressive breed. We also hypothesize that most participants will be opposed to breed ban legislation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

Survey respondents were recruited on 8 February 2022 through Prolific, an open online marketplace providing access to potential survey respondents in which survey respondents receive small monetary compensation for completing surveys (participants received $6.50 for completing this survey) [40]. The diversity of participants recruited through platforms such as Prolific is higher than that of typical Internet samples or North American college-based samples, and the quality of data collected meets standards considered acceptable in published research in the social sciences [41]. In order to minimize the influence of geographic and cultural differences on respondent data, the survey was made available only to adult (18 years or older) responders residing in the United States. The advertisement for the survey was simple, stating only that we were looking to obtain people’s opinions about certain dog breeds and laws about dog ownership.

2.2. Instrument

An online, anonymous, cross-sectional survey was developed using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Inc., Provo, UT, USA). The survey was modeled after the survey used to assess veterinarians’ views of dog breeds’ bite risk and breed restrictive legislation [39]. The original survey was developed and subsequently piloted by ten veterinarians. The current survey was also piloted by six researchers external to the research team, testing for ambiguous questions, question flow, and appropriate branching. Feedback from the pilot test was assessed and, when appropriate, incorporated into the final version of the survey. The study was approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Review Board (IRB #2293).

The survey began with an introduction that explained the purpose of the study and details designed to ensure participants had the information they needed to make informed consent to continue. These details included the fact that the survey was estimated to take approximately ten minutes to complete and there were no known risks involved in completing the survey. Participants were also given the contact information for Colorado State University Institutional Review Board and that of the primary investor. At the end of this information, participants were asked to indicate if they consented to continuing with the survey.

The survey began with a series of demographic questions (age, gender, children), their pet status, and local breed bans. The next section asked participants to indicate their level of agreement (i.e., strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree/disagree, agree, strongly agree), with statements pertaining to general dog ownership (e.g., “An adult should be able to own any breed of dog”); and breed bans (e.g., “Banning specific breeds improves public safety”). Next, participants were asked to rate a list of common dog breeds in terms of serious bite risk from the options of ‘minimal’, ‘moderate’, ‘high risk’, or ‘don’t know’. The list was derived from the most common breeds within the United States. The last section asked about participants’ endorsement of several dog-related laws that might affect public safety (e.g., “Stricter leash laws”, “Mandatory muzzling of specific breeds when in public”). The survey was between 13 and 15 pages (separate screens), depending on branching options, and most pages had between 3–6 questions. Participants could not go back within the survey to change their answers. The survey was developed with Qualtrics tools to help prevent multiple entries from the same person and bot responses.

Statistical analyses, including descriptive statistics and chi-square, and binary logistic regression, were conducted with IBM SPSS Version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). To analyze differences between participants based on whether they agreed or did not agree with several dog-related statements, the agreement statements were recoded into binary statements whereby ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ were combined into ‘agree’, and ‘neutral’, ‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’ were recoded into ‘disagree’ for analysis. Due to the number of analyses conducted, the significance level (α) was set at a more conservative level of p = 0.01.

3. Results

A total of 586 surveys were completed by adults residing in the United States. Of the potential participants who accessed the survey, two people chose not to participate. All participants who indicated they consented to the survey completed it in its entirety. The respondents were predominantly under the age of 40 (73%), non-Hispanic/Latinx (89%), White (78%), and included 286 (48.8%) females and 285 (48.6%) males, 10 (1.7%) nonbinary, and five (0.9%) who chose to not answer. The number of respondents who reported having children was 140 (24%). There was no difference in the number of males versus females in the likelihood of having children, pet dogs, or a dog of the Pit Bull type. Approximately half (54%) owned at least one dog (Table 1). Of those who owned a dog (n = 319), 36 (11%) indicated the dog(s) were of a Pit Bull type. For those who indicated they did not currently have a dog (n = 267), 232 (87%) indicated they would consider a dog as a pet and of these (n = 232), 126 (54%) reported they would consider a Pit Bull type dog as a pet. All participants were asked if they had ever been bitten by a dog, to which 249 (43%) said yes. Of those bitten, 55 (22%) indicated the bite required medical attention. There was no difference in the number of males versus females in the likelihood of having children, pet dogs, a dog of the Pit Bull type, having been bitten, or having a bite that required medical attention.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

3.1. Dog Aggression

Participants provided responses to four questions about dog aggression. Approximately half of respondents reported feeling that dog aggression against other dogs is a serious community/societal problem (51%), and that dog bites are a serious public health issue (49%). Most agreed, however, that owners of aggressive/dangerous dogs should be held legally accountable if their dog attacks/bites another dog (87%) or a person (91%) (Figure 1). No differences were found in responses based on gender, age, or child status. Of those who owned dogs, 8% (95% CI 3.5% to 13.1%) fewer, compared to non-owners, thought that owners of aggressive/dangerous dogs should be held legally accountable if their dog attacks a person (dog guardians: 278, 87%, compared to non-dog owners: 255, 96%; X2 = 12.34 (1), p < 0.001). Similarly, 7% fewer (95% CI 1.3% to 12.5%) dog guardians thought that owners of aggressive/dangerous dogs should be held legally accountable if their dog attacks another dog [(268 (84%) compared to 243 (91%) of non-dog guardians (X2 = 6.38 (1), p = 0.012)].

Figure 1.

Perceptions of dog aggression.

3.2. Breed and Breed Banning

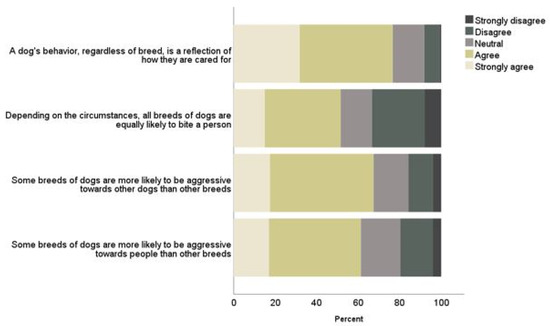

The next set of questions pertained to breed characteristics. The majority of respondents reported feeling that a dog’s behavior, regardless of breed, is a reflection of how they are cared for (77%). Most also reported feeling that some breeds of dogs are more likely to be aggressive towards other dogs (67%) or people (61%) than other breeds. Approximately half indicted they feel that, depending on the circumstances, all breeds of dogs are equally likely to bite a person (52%) (Figure 2). Twenty-one percent (95% CI 1.3% to 29.2%) more females agreed with this statement (177, 62%), compared to males (116, 41%; X2 = 25.65 (1), p < 0.001). No other differences in responses to the breed characteristics questions were found based on gender, child, or dog ownership status.

Figure 2.

Perceived association between dog breed and behavior.

Participants were next asked their views about breed specific legislation. Overall, participants were opposed to breed bans (398, 71%), whereas 88 (16%) supported a ban and 78 (14%) had no opinion. A binary linear regression analysis was conducted to determine predictors of support for a breed ban (yes/no). All variables were entered simultaneously. The binary regression model (Table 2) predicting support for breed ban using gender (male/female), age (under 30, 30–39 40–49,50–59, 60 and older), dog ownership, children status (yes/no), and dog bite history (yes/no) was significant (X2(8) = 29.48, p < 0.001). Gender was the only significant predictor of support for a breed ban (females were less likely to support a ban; B = 0.69; p = 0.008).

Table 2.

Results of the binary logistic regression model predicting support of breed ban as a function of child status, gender, dog ownership, bite status, and age.

Half of participants agreed that banning specific breeds creates an animal welfare issue (56%), and 64% felt that banning certain breeds of dogs is an overreach of governmental authority. Most also disagreed that particular dog breeds should not be allowed near children (71%) or that banning specific breeds of dogs improves public safety (82%). Seven percent (95% CI 0.1% to 13.1%) fewer females (32, 12%) reported supporting a ban than males (52, 19%); (X2 = 20.64 (2), p < 0.001); 15% (95% CI 7.1% to 22.3%) fewer females agreed that some breeds should not be allowed near children (63, 22%) compared to males (105, 37%), (X2 = 15.09 (1), p < 0.001), and 14% (95% CI 7.3% to 20.1%) fewer females agreed that specific breed bans improve public safety (30, 11%), compared to males (69, 24%; X2 = 18.75 (1), p < 0.001). Twenty percent (95% CI 11.7% to 27.5%) more females reported feeling that a ban is an overreach of governmental authority (213, 75%), compared to males (156, 55%), (X2 = 24.33 (1), p < 0.001) and 13% (95% CI 4.7% to 21.3%) more females reported feeling that banning creates an animal welfare issue (179, 63%; males: 141, 50%; X2 = 9.97 (1), p < 0.002). No differences were found based on child or dog ownership status.

Participants were also asked two questions about dogs and dog breeds as they relate to where they choose to live. When non-dog owners (n = 267) were asked how a neighborhood/complex that does not allow dogs would impact their decision to live there, 139 (52%) reported it would have no impact, 85 (32%) said they would be less likely to live there and 43 (16%) said they would be more likely to live there. Additionally, all participants were asked how a potential future neighbor who owns a dog breed with an aggressive reputation would impact their decision to live in that neighborhood or complex. To this question, 388 (66%) said it would have no impact, 191 (33%) said they would be less likely to live there, and 7 (1%) said more likely to live there.

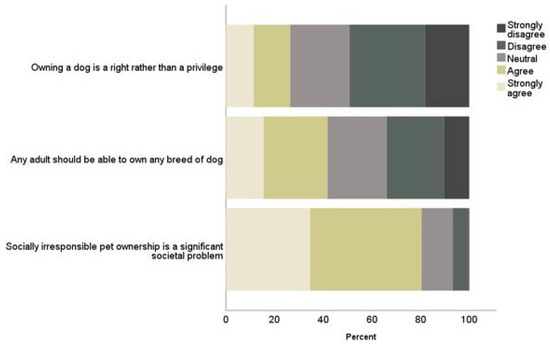

3.3. Pet Ownership

When asked about dog ownership, the vast majority of participants (80%) agreed that socially irresponsible pet ownership is a significant societal problem. Only one-quarter of participants reported feeling that owning a dog is a right rather than a privilege, and 42% indicated they felt that any adult should be able to own any breed of dog (Figure 3). No differences based on gender were found for any of the statements. Thirteen percent (95% CI 4.2% to 22.5%) more respondents with children agreed that owning a dog is a right rather than a privilege (51, 36%) compared to those with no children (104, 23%; X2 = 9.41 (1), p < 0.002). No other differences were found based on child or dog ownership status.

Figure 3.

Perceptions of pet ownership.

Participants were presented with a list of common breeds within the United States and asked to indicate their perception of the different breeds’ serious bite risk (defined as requiring medical treatment) as ‘minimal’, ‘moderate’, ‘high’, or ‘don’t know’. The only breed perceived by 50% or more of respondents as a high serious bite risk was the Pit Bull type (Table 3). Additional breeds reported as high risk by at least 25% of respondents included Rottweiler (43%), German Shepherd (36%), and Chihuahua (26%). The dog breeds with the lowest perceived risk of serious bites (5% or less of respondents rated them as a high risk) included Labrador Retriever (5%), Golden Retriever (5%), Yorkshire Terrier (5%), Dachshund (5%), Cocker Spaniel (4%), and Beagle (3%).

Table 3.

Serious Bite Risk Perception of Common Dog Breeds in the United States.

3.4. Community Policies

Participants were asked to indicate their support of several policies communities have enacted in an effort to increase public safety. The most commonly endorsed policies include public education about animal welfare (67%), animal behavior (66%), and stricter leash laws (58%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Participants’ endorsement of community policies enacted in efforts to increase public safety.

4. Discussion

Due to the frequency of dog bites in the United States, this study was designed to investigate United States’ adults’ perceptions of dog aggression, breed-specific legislation, and alternative community interventions in an effort to better understand the public’s perceptions of these key factors related to dog bites. The 586 participants in this study were predominately White, under 40 years of age, with no children. Approximately half of respondents reported owing a dog, 11% of which owned a Pit Bull. Most people who did not own a dog indicated they would consider a dog, and over half of these individuals would consider owning a Pit Bull. When queried about dog aggression and dog bites, only half of the participants reported feeling these issues are a serious community/societal problem or public health issue. Given the prevalence of dog bites, especially for young children, this suggests the need for public education about dog aggression. When asked to rate common breeds on serious bite risk, Pit Bulls were, by far, the breed rated highest, followed by Rottweilers, German Shepherds, Chihuahuas, and Doberman Pinschers. Yet Chow Chows were rated as high by only 18%, Huskies by 16%, Akitas by 12%, and Belgian Malinois by 13%. This can be contrasted with perceptions of small animal veterinarians who rated Chow Chows, Chihuahuas, German Shepherds, Rottweilers, Akitas, and Belgian Malinois as high risk (rated as high by 40% or more of participants) [39]. Other breeds rated as minimal risk by participants (e.g., Dalmatians, Cocker Spaniels) were viewed as higher risk by veterinarians [39].

Furthermore, only 52% of respondents reported feeling that, depending on the circumstances, all breeds of dogs are equally likely to bite a person, and only 24% felt that a dog’s behavior, regardless of breed, is a reflection of how they are cared for. Yet, due to numerous factors, there are little data to support the premise that breed is a good predictor of aggression. As Webster and Farnworth [33] note, the environment and a dog’s personality traits are better predictors of aggressive behavior than breed. This could help explain why dogs on banned lists do not cause the largest proportion of bites [42,43]. Additionally, bite proclivity by breed is difficult to calculate because information pertaining to breed populations within specific areas is typically unknown [44].

Instead of breed, other factors that have been shown to contribute to the likelihood of bite risk include dog attributes (e.g., male, unneutered), and negative dog/human interactions, such as chaining a dog in the yard, inadequate socialization, or harassing/teasing a dog [28,38,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Regardless of breed, the vast majority felt that owners of aggressive dogs should be held legally accountable if their dog attacks/bites another dog or person, although dog guardians were less inclined to support this premise. Yet, despite the number of stories in the media of stray aggressive dogs, most dog bites occur in or near the home by a dog known to the child and/or family [20,50].

Although the majority (71%) of participants opposed breed bans, males were less likely to oppose breed bans than females. Of all participants, however, only 56% felt bans create an animal welfare issue and nearly one in five reported feeling that that banning of specific breeds of dogs improves public safety. This can be compared to veterinarians’ views, in which 85% opposed breed bans and 75% felt they create an animal welfare issue [39]. In our study, females were less likely than males to support a breed ban, or to think bans improve public safety or that some breeds should not be allowed near children.

Despite opposition by many to breed-restrictive legislation, bans are still present in many cities and counties throughout the United States, with Pit Bulls often the banned breed [51]. This is problematic for several reasons. One central issue is that the Pit Bull is not actually a breed, but instead a group of breeds. The term ‘pit bull’ typically includes American and English Bulldogs, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, American Staffordshire Terriers and American Pit Bull Terriers, in addition to mixes of these and other breeds [31]. The determination of ‘pit bull’ is typically based on a dog’s physical resemblance to one of several breeds that have been associated with the term ‘pit bull’ [32,52]. Yet, most people, even animal professionals (e.g., breeders and animal shelter staff) are unable to accurately identify a Pit Bull [30,32,33,53,54,55]. Even human health care professionals’ reports about dog aggression are often inaccurate [28], with Pit Bulls often mis-identified and inaccurately labeled as dangerous [52,56]. A study by Bykowski and colleagues found that the breed of the involved dog is missing or assumed based on phenotypic characteristics in over 50% of dog bite medical reports for children, leading to compromised validity [57]. Another challenge is that more than half of the dogs in the United States are of mixed breed [58], yet most dog bite reports include only one breed [52]. These errors carry serious implications. For example, this is especially problematic when media stories about dog bites place an emphasis on dog breed [59]. Patronek [52] found that the breed involved in dog bite incidents reported in the media frequently differs when compared to animal control reports. Yet, even the CDC’s report on Dog Bite-Related Fatalities From 1979–1988 relied on media stories in which breed identification was based on physical appearance and stereotypes of Pit Bulls [60,61,62,63].

Likely due to numerous factors, several studies that have assessed the impact of dog breed bans have found them ineffective [43,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Additionally, breed bans have been described as expensive and difficult to implement, and to negatively affect canine welfare since many seized dogs spend long periods of time in kennels even if they have not specifically been involved in an incident [27,42,70,71,72].

When asked about alternative community policies instead of breed bans, the interventions rated highest included public education about animal welfare and animal behavior, and stricter leash laws. Approximately half of respondents also endorsed harsher penalties for dog owners in the event of a dog bite or attack, stricter laws about picking up dog waste, and stricter fencing or containment laws. These commonly endorsed community policies mirror those supported by veterinarians, although veterinarians reported even higher levels of endorsement [39].

The support for public education is perhaps unsurprising given that 80% of participants reported feeling that socially irresponsible pet ownership is a significant societal problem and over 50% disagreed with the sentiment that any adult should be able to own any breed of dog. The call for educating the public about dogs in general, and dog breeds and bite risk prevention in particular, has been voiced by both animal and human medical professionals alike [73,74,75,76,77]. It would appear the need is there; one recent study found that 70% of United States children have never received dog bite education and 88% of parents wish their children were educated about bite risks [78].

There are numerous dog bite prevention programs that teach children how to interact with unfamiliar dogs [13,79,80,81] or recognize potential risk factors with a family dog [82,83]; fewer programs address how to recognize and interpret specific dog body language including dogs’ behavioral responses and their stress signals [74]. Yet, an understanding of species-specific signaling and stress signs are critical in supporting positive human/dog interactions, especially in a home with young children [83,84,85].

Education about animal behavior can take many forms and, although many educational efforts target children, some studies have suggested that targeting caregivers rather than young children may be of equal or greater value [78,86,87]. One type of education that has been found helpful in promoting safer behaviors around dogs and positive human–animal interactions is hazard perception training [74,88], which may include some aspect of the ladder of aggression theory suggesting that dogs typically exhibit stress-related behaviors before snapping, growling, or biting [89].

Closely linked to education about animal behavior is animal welfare. Educational programs about animal welfare can foster positive relationships between dogs and people, reduce bite risk, and improve canine welfare [80,90,91]. More research exploring the impact of educational programs, for both children and adults in the areas of bite prevention and welfare, are needed to determine the best mode of delivery and presentation of the material to make a positive impact on subsequent dog/human interactions.

Limitations to the current study are those inherent in online surveys and these results cannot be generalized to the general United States population. Additionally, the survey questions pertained to participants’ self-reported opinions and perceptions, both of which have the potential to be biased. The topic of the survey may have impacted those who chose to participate, further leading to the potential for a biased sample. Further research pertaining to the public’s views of breed ban legislation and dog aggression is needed to better understand this challenging issue.

5. Conclusions

Dog bites and dog aggression are serious public health concerns and create a significant burden on emergency surgical resources [50,92]. In the United States, approximately 4.5 million dog bites occur annually and 20% of these bites become infected [93]. Dog bites rank as the 13th leading cause of nonfatal emergency department visits in the United States [20] and over 1000 people in the United States are treated in hospital emergency departments for nonfatal dog bite-related injuries daily [94]. Children are at particular risk; dog bites are one of the most common causes of non-fatal injury among children [95]. Unfortunately, the number of pediatric emergency visits due to dog bites has increased recently, felt to be associated with COVID-19 health restrictions resulting in children’s increased time at home [96]. Yet, since many bites go unreported, even these disturbingly high numbers are likely an underestimate of the actual prevalence [21].

In summary, this study found that most participants do not support a breed ban, but instead endorse education about animal welfare and behavior. This is in spite of the fact that one-third of respondents said that they would be less likely to live in a home with a neighbor who owns a dog breed with an aggressive reputation. This contradiction appears to reflect the complexity of this topic and suggests that many people struggle with conflicting feelings about dog breeds and their ability to predict aggression. Yet, the majority of participants in this study appear to understand that breed is a poor predictor of aggressive behavior and are open to alternative interventions that place more responsibility on dog guardians. These sentiments bode well for both canine welfare and public safety.

Author Contributions

Data curation, L.R.K.; Formal analysis, L.R.K.; Methodology, L.R.K., W.P., J.C.-M. and C.B.; Writing—original draft, L.R.K., W.P., P.E., J.C.-M. and C.B.; Writing—review & editing, L.R.K., W.P., P.E., J.C.-M. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Colorado State University (#2293 August 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available by request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Regina Schoenfeld-Tacher and James Oxley for their contributions to the conceptualization of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AVMA. Pet Population Still on the Rise, with Fewer Pets per Household; American Veterinary Medical Association: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.avma.org/javma-news/2021-12-01/pet-population-still-rise-fewer-pets-household (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Bussolari, C.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Packman, W.; Kogan, L.; Erdman, P. ‘I Couldn’t Have Asked for a Better Quarantine Partner!’: Experiences with Companion Dogs during COVID-19. Animals 2021, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, N.R.; Rodriguez, K.E.; Fine, A.H.; Trammell, J.P. Dogs Supporting Human Health and Well-Being: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 630465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, L.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Bussolari, C.; Packman, W.; Erdman, P. The Psychosocial Influence of Companion Animals on Positive and Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Animals 2021, 11, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, M.A.; Citron, L.; Shults, J.; Brown, D.C.; Serpell, J.A.; Farrar, J.T. Measuring Quality of Life in Owners of Companion Dogs: Development and Validation of a Dog Owner-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Edwards, K.M.; McGreevy, P.; Bauman, A.; Podberscek, A.; Neilly, B.; Sherrington, C.; Stamatakis, E. Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaauw, P.A.; Vinke, C.M.; Van Hagen, M.A.; Lipman, L.J. A One Health Perspective on the Human–Companion Animal Relationship with Emphasis on Zoonotic Aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; Hediger, K. Pet Ownership and Human–Animal Interaction in an Aging Population: Rewards and Challenges. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, N.; Lagueux, É.; Michaud, F.; Provencher, V. Pros and cons of pet ownership in sustaining independence in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review. Ageing Soc. 2019, 40, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, H.; Greenheld, N.; Goddard, R. Beware of the dog? An observational study of dog-related musculoskeletal injury in the UK. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 46, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.A.; Mistry, R.D. Dog Bites in Children Surge during Coronavirus Disease-2019: A Case for Enhanced Prevention. J. Pediatr. 2020, 225, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, N.R.; Mueller, M.K. A Systematic Review of Research on Pet Ownership and Animal Interactions among Older Adults. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Rouse, J.; Godbole, M.; Wells, H.L.; Boppana, S.; Schwebel, D.C. Systematic Review: Interventions to Educate Children About Dog Safety and Prevent Pediatric Dog-Bite Injuries: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 42, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, R.A.; Loftus, B.; Bolster, C.; Richards, G.J.; Blackwell, E.J. Human directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; New, J.J.G.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H.; Ruch-Gallie, R.; Hetts, S. Human and Animal Factors Related to Relinquishment of Dogs and Cats in 12 Selected Animal Shelters in the United States. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1998, 1, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Sun, L. Factors associated with aggressive responses in pet dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 123, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, V.; Sottiaux, M.; Appelboom, J.; Kahn, A. Posttraumatic stress disorder after dog bites in children. J. Pediatr. 2004, 144, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramgopal, S.; Brungo, L.B.; Bykowski, M.R.; Pitetti, R.D.; Hickey, R.W. Dog bites in a U.S. county: Age, body part and breed in paediatric dog bites. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AVMA. Dog Bite Prevention; American Veterinary Medical Association: Schaumburg, IL, USA. Available online: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/pet-owners/dog-bite-prevention (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Tuckel, P.S.; Milczarski, W. The changing epidemiology of dog bite injuries in the United States, 2005–2018. Inj. Epidemiol. 2020, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Brooke, M.; Christley, R.M. How many people have been bitten by dogs? A cross-sectional survey of prevalence, incidence and factors associated with dog bites in a UK community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASPCApro. Filling the Pit. 2019. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20190731184541/https://www.aspcapro.org/blog/2014/05/15/filling-pit (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Hawes, S.M.; Flynn, E.; Tedeschi, P.; Morris, K.N. Humane Communities: Social change through policies promoting collective welfare. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 44, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudies, C.; Waiblinger, S.; Arhant, C. Characteristics and Welfare of Long-Term Shelter Dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASPCA. What Is Breed-Specific Legislation? Available online: https://www.aspca.org/animal-protection/public-policy/what-breed-specific-legislation (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Tenter, A.R. Citizens’ Beliefs Regarding Dog Breed-Specific Legislation. The Case of Romania. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, R.; Orihel, J.; Clarke, N.; Murphy, S.; Sedlbauer, M. Breed specific legislation: Considerations for evaluating its effectiveness and recommendations for alternatives. Can. Vet. J. 2005, 46, 735–743. [Google Scholar]

- Arluke, A.; Cleary, D.; Patronek, G.; Bradley, J. Defaming Rover: Error-Based Latent Rhetoric in the Medical Literature on Dog Bites. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 21, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, L.M.; Barber, R.; Wynne, C.D.L. A canine identity crisis: Genetic breed heritage testing of shelter dogs. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Harrison, N.; Wolff, L.; Westgarth, C. Is That Dog a Pit Bull? A Cross-Country Comparison of Perceptions of Shelter Workers Regarding Breed Identification. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, R.; Rindy, K. Are ‘Pit Bulls’ Different? An Analysis of the Pit Bull Terrier Controversy. Anthrozoös 1987, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voith, V.L.; Ingram, E.; Mitsouras, K.; Irizarry, K. Comparison of adoption agency breed identification and DNA breed identification of dogs. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2009, 12, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Farnworth, M.J. Ability of the Public to Recognize Dogs Considered to Be Dangerous under the Dangerous Dogs Act in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 22, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.; Mills, D.; Cooper, J. ‘Type’ as Central to Perceptions of Breed Differences in Behavior of Domestic Dog. Soc. Anim. 2016, 24, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Oxley, J.; Hogue, T.; Mills, D.S. The representation of aggressive behavior of dogs in the popular media in the UK and Japan. J. Veter. Behav. 2014, 9, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrose, V.T.; Squibb, K.; Hazel, S.; Kogan, L.R.; Oxley, J.A. Dog bites dog: The use of news media articles to investigate dog on dog aggression. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, L. Dog on a Tightrope: The Position of the Dog in British Society as Influenced by Press Reports on Dog Attacks (1988 to 1992). Anthrozoös 1994, 7, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.A.; Vertalka, J.J. Understanding Dog Bites: The Important Role of Human Behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 24, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L.R.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R.M.; Hellyer, P.W.; Oxley, J.A.; Rishniw, M. Small Animal Veterinarians’ Perceptions, Experiences, and Views of Common Dog Breeds, Dog Aggression, and Breed-Specific Laws in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolific. Quickly Find Research Participants You Can Trust. Available online: https://www.prolific.co/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Buhrmester, M.D.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New Source of Inexpensive, Yet High-Quality, Data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedon, N.; Súilleabháin, P.S. Dog bite injuries to humans and the use of breed-specific legislation: A comparison of bites from legislated and non-legislated dog breeds. Ir. Veter. J. 2017, 70, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, B.; García-Belenguer, S.; León, M.; Palacio, J. A comprehensive study of dog bites in Spain, 1995–2004. Vet. J. 2009, 179, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association Task Force on Canine Aggression and Human-Canine Interactions, “A community approach to dog bite prevention. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1732–1749. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, N.; Rock, M.; Schmidtz, O.; Anderson, D.; Parkinson, M.; Checkley, S.L. Insights about the Epidemiology of Dog Bites in a Canadian City Using a Dog Aggression Scale and Administrative Data. Animals 2019, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, R.L. Human fatalities resulting from dog attacks in the United States, 1979–2005. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2009, 20, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messam, L.L.M.; Kass, P.H.; Chomel, B.B.; Hart, L.A. Factors Associated with Bites to a Child From a Dog Living in the Same Home: A Bi-National Comparison. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzycki, A.; Simpson, A.; Williams, J. Dog bites in the emergency department: A descriptive analysis. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 21, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, J.A.; Christley, R.; Westgarth, C. Contexts and consequences of dog bite incidents. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 23, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Horswell, B.B.; Samanta, D. Dog-Bite Injuries to the Craniofacial Region: An Epidemiologic and Pattern-of-Injury Review at a Level 1 Trauma Center. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 78, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, S. The Dangerous Dog Debate. 2017. Available online: https://www.avma.org/news/javmanews/pages/171115a.aspx (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Patronek, G.J.; Sacks, J.J.; Delise, K.M.; Cleary, D.V.; Marder, A.R. Co-occurrence of potentially preventable factors in 256 dog bite–related fatalities in the United States (2000–2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 243, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, M.A.; Carleton, C.L.; Reese, L.A. Beloved Companion or Problem Animal. Soc. Anim. 2019, 27, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.; Levine, E. The need for a co-ordinated scientific approach to the investigation of dog bite injuries. Vet. J. 2006, 172, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.; Levy, J.; Norby, B.; Crandall, M.; Broadhurst, J.; Jacks, S.; Barton, R.; Zimmerman, M. Inconsistent identification of pit bull-type dogs by shelter staff. Vet. J. 2015, 206, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, L.M.; Barber, R.T.; Wynne, C.D.L. What’s in a Name? Effect of Breed Perceptions & Labeling on Attractiveness, Adoptions & Length of Stay for Pit-Bull-Type Dogs. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, M.R.; Shakir, S.; Naran, S.; Smith, D.M.; Goldstein, J.A.; Grunwaldt, L.; Saladino, R.A.; Losee, J.E. Pediatric Dog Bite Prevention: Are We Barking Up the Wrong Tree or Just Not Barking Loud Enough? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2017, 35, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSUS. Pets by the Numbers. HumanePro 2021. Available online: https://humanepro.org/page/pets-by-the-numbers (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Mouton, M.; Boulton, A.; Solomon, O.; Rock, M. ‘When the dog bites’: What can we learn about health geography from newspaper coverage in a ‘model city’ for dog-bite prevention? Health Place 2019, 57, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patronek, G.; Twining, H.; Arluke, A. Managing the Stigma of Outlaw Breeds: A Case Study of Pit Bull Owners. Soc. Anim. 2000, 8, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patronek, G.J.; Bradley, J.; Cleary, D. Who is minding the bibliography? Daisy chaining, dropped leads, and other bad behavior using examples from the dog bite literature. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 14, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, P. Breed-Specific Dog Laws: Moving the United States Away from an Anti-Pit Bull Mentality. J. Anim. Nat. Resour. 2018, 14, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, J.J.; Sattin, R.W.; Bonzo, S.E. Dog bite-related fatalities from 1979 through 1988. JAMA 1989, 262, 1489–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchieri, B. Targeting the Wrong End of the Leash: Why Breed-Specific Legislation is Futile without Responsible Pet ownership and Unbiased Media. Ava Maria Law Rev. 2018, 16, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen, J.M.; Hopster, H. Dog bites in The Netherlands: A study of victims, injuries, circumstances and aggressors to support evaluation of breed specific legislation. Vet. J. 2010, 186, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Ciceroni, C.; Sighieri, C. Italian breed-specific legislation on potentially dangerous dogs (2003): Assessment of its effects in the city of Florence (Italy). Dog Behav. 2015, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, E.; Fonseca, G.M.; Navarro, P.; Castaño, A.; Lucena, J. Fatal dog attacks in Spain under a breed-specific legislation: A ten-year retrospective study. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 25, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilson, F.; Damsager, J.; Lauritsen, J.; Bonander, C. The effect of breed-specific dog legislation on hospital treated dog bites in Odense, Denmark—A time series intervention study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutzel, J. Pit Bull Ban a Waste of Taxpayer Dollars; Platte Institute for Economic Research: Omaha, NE, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley, J.; Gaines, S. The Welfare Implications as a Result of Breed Specific Legislation in the UK. In Proceedings of the UFAW International Animal Welfare Symposium, Surrey, UK, 29–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley, J.; Shepherd, K. Need for welfare-related research on seized dogs. Vet. Rec. 2012, 171, 569–570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stephen, J.M.; Ledger, R.A. An Audit of Behavioral Indicators of Poor Welfare in Kenneled Dogs in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2005, 8, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, M.; Oxley, J.A.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Westgarth, C. Pet dog bites in children: Management and prevention. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2020, 4, e000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meints, K.; Brelsford, V.; De Keuster, T. Teaching Children and Parents to Understand Dog Signaling. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Christley, R.; Watkins, F.; Yang, H.; Bishop, B.; Westgarth, C. Dog bite safety at work: An injury prevention perspective on reported occupational dog bites in the UK. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, G.; Gargano, T.; Di Mitri, M.; Cravano, S.; Thomas, E.; Vastano, M.; Maffi, M.; Libri, M.; Lima, M. Consequences of COVID-19 Lockdown on Children and Their Pets: Dangerous Increase of Dog Bites among the Paediatric Population. Children 2021, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.N.; Horvath, K.Z.; Minneci, P.C.; Thakkar, R.; Wurster, L.; Noffsinger, D.L.; Bourgeois, T.; Deans, K.J. Pediatric dog bite injuries in the USA: A systematic review. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 5, e000281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.A.; Mahabee-Gittens, E.M.; Hart, K.W.; Lindsell, C.J. Dog Bite Prevention: An Assessment of Child Knowledge. J. Pediatr. 2012, 160, 337–341.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Cornwall, J.; Righetti, J.; Sung, L. Preventing dog bites in children: Randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention. BMJ 2000, 320, 1512–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.D.; Williams, J.M. Assessing Effectiveness of a Nonhuman Animal Welfare Education Program for Primary School Children. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kienesberger, B.; Arneitz, C.; Wolfschluckner, V.; Flucher, C.; Spitzer, P.; Singer, G.; Castellani, C.; Till, H.; Schalamon, J. Child safety programs for primary school children decrease the injury severity of dog bites. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 181, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, C.A.; Pomerantz, W.J.; Hart, K.W.; Lindsell, C.J.; Mahabee-Gittens, E.M. An Evaluation of a Dog Bite Prevention Intervention in the Pediatric Emergency Department. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, S308–S312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meints, K.; De Keuster, T. Brief Report: Don’t Kiss a Sleeping Dog: The First Assessment of ‘The Blue Dog’ Bite Prevention Program. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Starling, M.; Branson, N.; Cobb, M.; Calnon, D. An overview of the dog–human dyad and ethograms within it. J. Vet. Behav. 2012, 7, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, I.R.; Shofer, F.S.; Nance, M.L. Behavioral assessment of child-directed canine aggression. Inj. Prev. 2007, 13, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhant, C.; Beetz, A.M.; Troxler, J. Caregiver Reports of Interactions between Children up to 6 Years and Their Family Dog—Implications for Dog Bite Prevention. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.A.; Sasor, S.E.; Soleimani, T.; Chu, M.W.; Tholpady, S.S. An Epidemiological Analysis of Pediatric Dog Bite Injuries Over a Decade. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 246, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christley, R.; Nelson, G.; Millman, C.; Westgarth, C. Assessment of Detection of Potential Dog-Bite Risks in the Home Using a Real-Time Hazard Perception Test. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, K. Ladder of aggression. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Behavioural Medicine; British Small Animal Veterinary Association: Gloucester, UK, 2009; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baatz, A.; Anderson, K.L.; Casey, R.; Kyle, M.; McMillan, K.M.; Upjohn, M.; Sevenoaks, H. Education as a tool for improving canine welfare: Evaluating the effect of an education workshop on attitudes to responsible dog ownership and canine welfare in a sample of Key Stage 2 children in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notari, L.; Cannas, S.; Di Sotto, Y.A.; Palestrini, C. A Retrospective Analysis of Dog–Dog and Dog–Human Cases of Aggression in Northern Italy. Animals 2020, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loder, R.T. The demographics of dog bites in the United States. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Preventing Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 May 2015. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/features/dog-bite-prevention/ (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Dogsbite, Quick Statistics—DogsBite.org. DogsBite.org-Some Dogs Don’t Let Go. Available online: https://www.dogsbite.org/dog-bite-statistics-quick-statistics.php (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- CDC. Nonfatal Injury Data. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal.html (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Tulloch, J.S.P.; Minford, S.; Pimblett, V.; Rotheram, M.; Christley, R.M.; Westgarth, C. Paediatric emergency department dog bite attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic: An audit at a tertiary children’s hospital. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).